Consider the Following:

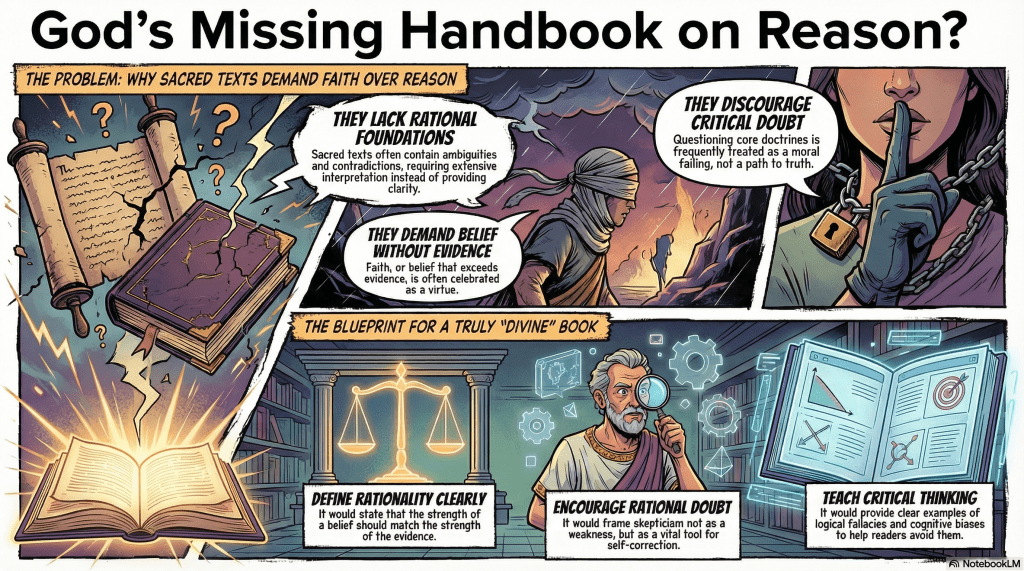

Summary: This piece questions whether a truly divine text would lack essential qualities like clarity, logic, consistency, epistemic standards, and encouragement toward skeptical inquiry, arguing that such omissions cast doubt on its divine origin. It suggests that a book from an all-knowing deity should inherently guide readers through rational principles, rather than relying solely on faith with low dependence on the relevant evidence.

A Rational Bible?

Imagine a scholar named Amelia sitting in a quiet library, leafing through a text alleged to have been written by a God who is fully rational. While she admires the moral teachings and poetic beauty of certain passages, she finds herself increasingly troubled by their ambiguity and contradictions. If this text is indeed authored by a rational deity, why does it require such extensive interpretation by “experts”, leading to divergent doctrines and confusion among believers? As Amelia reflects, she questions why the text does not embody the clarity, logic, and universality one would expect from a divine source, instead seeming to demand faith over rational inquiry. These concerns push her to wonder: Could a truly divine text fail to meet the very standards it ought to set for truth, understanding, and intellectual engagement?

Expected elements of an truly rational book written by an actual rational God.

A clear statement on the definition of rationality

A book claiming to be a source of truth and rationality must define rationality clearly and comprehensively. A robust definition, such as “Rational belief is a degree of belief that maps to the degree of the relevant evidence,” is essential for creating a foundation upon which further claims and arguments can be assessed. This definition emphasizes the importance of proportional belief, rejecting absolutist or dogmatic views where beliefs are based on tradition, authority, or intuition without critical examination. By centering rationality on evidence, the book ensures that the epistemic framework can adapt to new information, fostering ongoing inquiry and intellectual growth.

- Does the Christian Bible contain this clear statement on the definition of rational thought?

A clear rejection of all other epistemologies, such as faith

For consistency, the book should explicitly reject competing epistemologies, particularly those like faith-based models, where belief is not proportioned to evidence. Faith-based epistemologies typically involve asserting certainty without sufficient or any evidence, often resulting in a fixed worldview. The book should critique these models on their failure to promote testability, falsifiability, or intellectual accountability. This rejection must include examples demonstrating how alternative models lead to epistemic errors, such as the inability to self-correct in the face of disconfirming evidence, making them unreliable pathways to truth.

- Does the Christian Bible clearly reject all epistemologies that entail a degree of belief that exceeds the degree of the evidence?

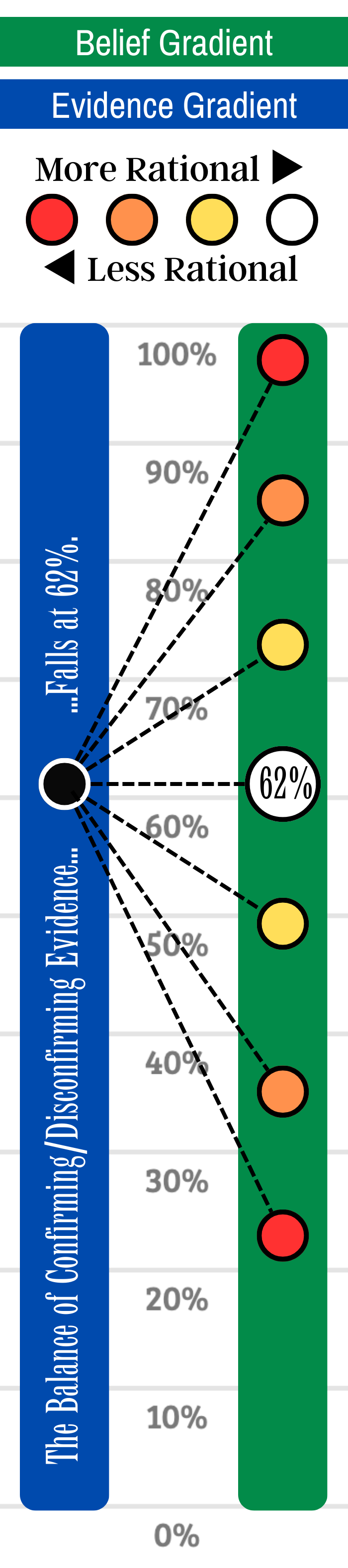

A clear description of the epistemic gradient

An effective framework for rationality requires an explanation of the epistemic gradient, which emphasizes that belief is not binary (i.e., either fully believed or fully doubted). Instead, beliefs exist along a spectrum of credences, ranging from near-certainty to deep skepticism. This spectrum reflects varying degrees of confidence based on the quality and quantity of evidence. Rejecting binary thinking encourages readers to update their beliefs incrementally as new evidence emerges, promoting intellectual humility and flexibility in reasoning. The book should also illustrate how binary belief models can lead to dogmatism and cognitive inflexibility.

- Does the Christian Bible reject binary belief and describe and encourage a gradient notion of rational belief?

Encouragement of rational doubt

The book should underscore the importance of rational doubt, which is the complement to belief on the epistemic gradient. Rational doubt is not the rejection of all claims but rather a skeptical stance proportionate to the evidence. This concept encourages readers to challenge their own assumptions and the claims of others without succumbing to cynicism or radical skepticism. By promoting doubt that is mapped to weak or absent evidence, the book fosters intellectual resilience—readers learn to neither dismiss new ideas prematurely nor accept them uncritically. Rational doubt ensures beliefs remain dynamic and responsive to the evolving state of knowledge.

- Does the Christian Bible encourage rational doubt or does it instead treat doubt as a weakness?

A rejection of any reward for disproportionate belief

To solidify its epistemic authority, the book must clearly reject reward systems that incentivize belief disproportionate to evidence. In many faith-based or ideological systems, belief without evidence—or even in defiance of evidence—is celebrated as virtuous. This book must condemn such rewards as harmful to intellectual development and the pursuit of truth. It should argue that epistemic virtue lies in the responsible calibration of belief and doubt according to evidence. Examples should highlight the dangers of awarding unquestioning belief, such as promoting dogma, groupthink, and misinformation.

- Does the Christian Bible reward a degree of belief that exceeds the degree of relevant evidence?

Ample, salient examples of common logical fallacies and cognitive biases

Finally, the book should provide ample, contextually relevant examples of the most common logical fallacies and cognitive biases to help readers identify and overcome these errors. Examples might include:

- Confirmation Bias: Favoring information that confirms one’s existing beliefs.

- Vested Interests: The psychological reluctance to give up an erroneous position if much time, energy, and resources have invested in that position.

- Fear-based Ideology Selection: The natural human inclination to accept ideologies based on fear-alleviating promises instead of evidence.

- Emotion Reification: The very human tendency to view emotions as confirmation of the truth of the ideology that evokes those emotions.

- Does the Christian Bible include a sufficient number of clear examples of factors leading to poor thinking?

Each example should come with explanations of how these fallacies undermine rational inquiry and how to avoid them. The book should also highlight cognitive pitfalls like anchoring and availability heuristics to demonstrate how human psychology can interfere with rational decision-making. The goal is to equip readers with practical tools to enhance critical thinking and minimize irrational influences in both personal and public discourse.

These questions probes deeply into the authenticity of religious texts, particularly whether a truly rational deity would create a sacred text lacking in rational thought and foundational principles of belief. We explore this question by examining the qualities listed above that one would expect from a divinely inspired book and analyzing where such texts may fall short. The aim is to understand if a book, purportedly authored by a deity, aligns with what we would logically expect from an being rational in its very essence.

A Focus on the Nature of Faith and the Demand for Evidence

In many religions, faith is prioritized over evidence, often seen as a virtue. However, an insistence on faith without supporting evidence raises an essential question: Would an omnipotent deity rely on faith alone to validate belief, or would such a deity empower believers with clear evidence and rational explanations? The emphasis on faith without sufficient support suggests a lack of alignment with the principles of rationality and intellectual honesty that humans value.

◉ Relevant: Textual Survey of Biblical Faith

Conclusion: A Test of Divine Authorship?

If a sacred book lacks the essentials of rational belief, rational doubt, and the encouragement of an exploration of all opinions on all sides, it becomes challenging to affirm its divine origin. For a work to truly reflect the wisdom of an all-knowing deity, it would logically embody these qualities to guide human understanding. Therefore, the absence of these elements raises serious questions about the authenticity of such texts as divinely inspired works.

It is worth considering whether the Bible, or any alleged “Word of God“, contains these elements crucial to building a foundation of truth.

◉ See also: Rationality vs Faith

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Clarity and Accessibility

- Premise 1: An all-knowing deity would produce a text that is clear and accessible to all people, accommodating human limitations.

- Premise 2: The Bible and many sacred texts contain ambiguities and require extensive interpretation, leading to confusion.

- Conclusion: Therefore, it is unlikely that the Bible, or any ambiguous sacred text, is authored by an all-knowing deity.

Argument 2: Foundational Principles of Rational Thought

- Premise 1: A book authored by a truly divine being would include core principles of logic and evidence to guide rational evaluation of its teachings.

- Premise 2: The Bible and similar texts lack explicit guidance on core principles of rational thought and instead demand belief without evidence.

- Conclusion: Hence, it is improbable that a truly divine book would exclude essential principles of logic and evidence.

Argument 3: Consistency and Universality

- Premise 1: A divinely authored text would be consistent and universally applicable, free of internal contradictions and cultural biases.

- Premise 2: The Bible and other sacred texts contain inconsistencies and teachings limited to specific cultural contexts.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the inconsistent and culturally bound nature of these texts suggests they may not be the work of a divine author.

Argument 4: Encouragement of Critical Inquiry

- Premise 1: A genuine deity would encourage critical inquiry and reasoned doubt to foster intellectual growth.

- Premise 2: Many religious texts discourage questioning and label doubt as sinful or morally wrong.

- Conclusion: Thus, the lack of encouragement for critical inquiry in these texts casts doubt on their divine authorship.

Argument 5: The Nature of Faith vs. Evidence

- Premise 1: A benevolent deity would likely provide clear evidence to support belief rather than relying solely on faith.

- Premise 2: Religious texts often emphasize faith without evidence, suggesting belief should stand without rational support.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the emphasis on faith over evidence raises questions about the texts’ alignment with divine wisdom and rationality.

◉ Survey of Biblical Faith

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Would a Divine Text Lack Rational Foundations?

CHRIS: Faith means believing in God even when we don’t have full evidence. It’s about trusting in something greater than what’s rationally provable.

CLARUS: But, Chris, if faith is belief that exceeds evidence, doesn’t that sound like intellectual surrender? If the Bible were truly divine, wouldn’t it emphasize rational principles and guide us to proportion our beliefs to the evidence? Instead, it asks for faith over reason, which seems strange if it’s from an all-knowing deity.

CHRIS: But faith is meant to go beyond reason, as an act of devotion. Isn’t there value in believing in something that we can’t fully see or prove?

CLARUS: Value in surrendering reason? I think not. A divine book would logically offer clear evidence and encourage belief based on that evidence, not demand that we believe more than is justified. The fact that the Bible lacks this rational structure—that it actually encourages us to set reason aside—seems inconsistent with what we’d expect from a rational God.

CHRIS: Faith might require us to go beyond reason, but it’s about building a relationship with God, not just adhering to logic.

CLARUS: But if a God exists and is truly wise, wouldn’t He know that rational beings need to see logic and evidence in order to genuinely trust? Faith that ignores evidence isn’t a relationship; it’s a demand for a degree of allegiance not warranted by the degree of evidence. An all-knowing deity wouldn’t need to ask us to believe beyond what we can verify—He would ground belief in rational foundations that strengthen our understanding.

CHRIS: But doesn’t the Bible provide guidance and moral lessons? Isn’t that enough, even if it doesn’t provide all the evidence?

CLARUS: Guidance, maybe, but a truly divine book would go further. It would give clear, rational guidance that aligns belief with the evidence at hand. Yet, the Bible falls short of providing the logical clarity we’d expect—it often appeals to faith that exceeds reason rather than supporting belief through coherent, rational arguments. Doesn’t that feel like a flaw, not a virtue?

CHRIS: Perhaps the Bible assumes we’re meant to have faith beyond reason. That’s a test of our trust in God.

CLARUS: But a God who values truth wouldn’t make trust a matter of abandoning reason. Belief without evidence isn’t a test—it’s a trap that leaves people vulnerable to accepting anything. A truly divine book would invite critical thought and questioning. If God’s word can’t withstand rational scrutiny and instead asks us to believe without reason, that suggests human authorship, not divine insight.

CHRIS: Still, faith provides a sense of purpose and hope. Isn’t that valuable, even if it goes beyond evidence?

CLARUS: Hope and purpose are valuable, but not when they’re built on unfounded beliefs. Real purpose should stand up to rational testing, not demand belief beyond reason. A genuinely divine message would ground us in truth, not ask us to abandon evidence. The fact that the Bible lacks this rational structure raises doubts about its divine origin—it relies on faith, rather than encouraging us to use our full intellectual capacity.

CHRIS: But faith can be seen as humility, accepting that there are things beyond our understanding.

CLARUS: Humility isn’t ignoring evidence; it’s recognizing our limits through reason. A divine book would account for our need for rational grounding and wouldn’t rely on belief without evidence. Faith that demands we overlook the lack of rationality in the Bible isn’t humility—it’s just giving up our intellectual integrity. An all-knowing God wouldn’t require that of us.

CHRIS: So you believe faith that exceeds evidence is misguided?

CLARUS: Yes, absolutely. Faith that requires belief beyond evidence isn’t wisdom—it’s intellectual overreach. A true pursuit of truth would keep belief in line with what’s rationally supported. A divine book wouldn’t sideline logic and evidence; it would embody them. Faith that dismisses reason isn’t divine—it’s a demand for loyalty that leaves truth behind.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Unreliable Map

Imagine you’re handed a map that claims to guide you to a valuable treasure, but it’s riddled with incomplete paths, contradictions, and missing landmarks. When you ask for clarification, you’re told to trust the map without questioning its gaps or errors. In any other context, you’d discard such a map because true guidance should provide clear, rational directions. Similarly, if the Bible were truly divine, it would be a map of truth grounded in logic and evidence, not one that requires faith beyond reason to accept its inconsistencies.

Analogy 2: The Courtroom with No Evidence

Imagine a courtroom where the judge expects you to believe in the guilt or innocence of someone without presenting ample evidence. You’re told that your trust in the system is more important than the facts of the case. In reality, justice relies on evidence and rational examination to prevent misplaced belief. If the Bible were authored by a just and all-knowing God, it would lay out evidence and encourage rational scrutiny, not demand faith beyond what is rationally supported.

Analogy 3: The Safety Manual Missing Key Instructions

Consider a safety manual for a complex machine, intended to prevent accidents and guide users properly. If the manual were unclear, lacking logical order, or if it left out essential instructions, you’d question its reliability, as genuine safety depends on precision and clarity. Just as a good safety manual would give clear, rational guidance, a divine text should be logically consistent and grounded in evidence. A book asking for faith over evidence would be like a manual that leaves its readers vulnerable to misunderstanding and error.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Faith as a Necessary Part of Divine Relationship

Some theologians argue that faith is a core component of a relationship with God, specifically because it goes beyond evidence. They suggest that a relationship based purely on rational proof would reduce trust to a transactional level, while faith invites believers to experience trust, devotion, and commitment without needing absolute evidence. From this perspective, faith exceeding the evidence reflects a relationship of love and loyalty, rather than simply a logical contract.

2. Mystery as an Essential Aspect of Divine Revelation

Theologians often emphasize that mystery is inherent in any divine revelation. They argue that God’s infinite wisdom is, by nature, beyond human understanding, and that some aspects of divinity cannot be fully comprehended through logic alone. In this view, the apparent lack of rational principles in the Bible is not a flaw but an acknowledgment of human limitations in grasping divine truth. Faith, therefore, allows believers to approach these mysteries with humility, understanding that not everything divine can be fully rationalized.

3. Evidence Through Personal Experience and Transformation

Some theologians suggest that the Bible’s evidence isn’t always logical or empirical but is found in the transformative power it has in people’s lives. They argue that the proof of faith lies in the personal experiences of believers who feel changed and renewed by their relationship with God. For these theologians, the Bible’s lack of explicit rational principles does not undermine its validity; rather, it indicates that truth can also be felt and lived, beyond the confines of rational evidence.

4. Faith as a Test of Free Will and Devotion

Another theological response is that faith serves as a test of free will and devotion. The idea is that if God provided incontrovertible rational proof of His existence, there would be no genuine choice or freedom in believing. Faith that exceeds evidence, they argue, allows humans to make a free and meaningful choice to believe, rather than being compelled by undeniable proof. This choice to believe without complete evidence reflects true devotion and the exercise of free will.

5. Rationality and Faith as Complementary Paths to Truth

Some theologians maintain that rationality and faith are not opposed but are complementary means of understanding truth. They suggest that while reason guides us in worldly matters, faith provides access to higher truths that transcend human logic. In this view, the Bible’s emphasis on faith is an invitation to seek knowledge through both reason and belief, recognizing that divine truths may require trust in things beyond what reason alone can verify.

Counter-Responses

1. Faith as a Necessary Part of Divine Relationship

If faith is defined as belief beyond evidence, then grounding a divine relationship in such faith encourages intellectual submission rather than genuine understanding. A truly rational God would likely desire relationships founded on truth and reason, allowing believers to comprehend and trust based on solid evidence rather than unwarranted allegiance. By invoking a faith that exceeds evidence, this approach fails to respect the human need for rational grounding and instead encourages a dependence that bypasses critical inquiry—a requirement that would seem counterintuitive for an omniscient deity who values intellectual integrity.

2. Mystery as an Essential Aspect of Divine Revelation

While some mystery may be expected in any conception of the divine, the notion that rational principles and clarity are optional seems unreasonable if the goal is genuine understanding. A rational God would anticipate human limits and create a revelation that bridges the gap between the infinite and the finite in a way that humans can grasp. Encouraging faith beyond evidence by invoking “mystery” runs the risk of excusing lack of coherence rather than reflecting divine wisdom. If divine truths cannot be communicated logically and rationally, then it’s unclear how they can claim universal applicability or be meaningful in guiding human thought.

3. Evidence Through Personal Experience and Transformation

Personal experiences, while compelling on an individual level, cannot substitute for objective evidence when determining universal truth. Subjective transformations are not exclusive to one faith and can be seen across various belief systems, often contradicting one another. If a rational God’s truth were objectively verifiable, it would not rely on subjective transformations but would include consistent, observable evidence accessible to all. Basing belief on personal experience alone opens the door to confirmation bias and fails to provide a standard for evaluating the truthfulness of religious claims objectively.

4. Faith as a Test of Free Will and Devotion

The concept of faith as a test of free will and devotion assumes that rational evidence would somehow coerce belief. However, reasoned belief does not eliminate free will; it simply allows for informed choice. Belief that exceeds evidence risks turning faith into intellectual submission, where one’s devotion is untested by reason. A rational God would respect free will by encouraging beliefs that align with evidence-based reasoning, allowing humans to use their intellectual faculties fully without abandoning discernment.

5. Rationality and Faith as Complementary Paths to Truth

Suggesting that rationality and faith are complementary paths to truth is problematic if faith entails belief that exceeds evidence. Rational inquiry is inherently cautious, seeking beliefs proportionate to the evidence available. Introducing faith as a means of understanding “higher truths” disregards the principles of logical coherence and evidential support required for genuine knowledge. If a truly rational God wanted to impart universal truth, it would be consistent, grounded in evidence, and accessible through reason—rather than requiring faith that surpasses rational verification.

Clarifications

Rational Belief as Proportionate to Evidence: A Defense

In any discussion about belief, particularly rational belief, a central question arises: what makes a belief rational, and how do we evaluate this rationality? One robust answer is that rational belief is a belief whose degree matches the degree of relevant evidence. This principle grounds rational belief in proportionality, demanding that the strength of one’s belief aligns directly with the strength of the evidence. This essay defends this principle as a standard for rationality, showing that beliefs deviating from evidence become increasingly irrational in proportion to this deviation. Such a standard fosters intellectual integrity, accountability, and a commitment to truth-seeking.

The Core Principle of Proportionality

To call a belief rational implies that it is not arbitrary but reasoned and justified. For this to hold, a rational belief must correspond to the evidence available. When we say that a belief is “proportionate” to the evidence, we mean that the level of conviction aligns with how much the evidence supports it. If there is strong, conclusive evidence, then a strong belief is justified; if there is weak or ambiguous evidence, a correspondingly modest belief is rational. This principle aligns with the philosophical maxim that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence—that is, belief should not exceed what the evidence justifies.

The Pitfalls of Belief Beyond Evidence

When belief exceeds the degree of evidence, it enters the realm of irrationality, exposing the believer to potential errors, misinterpretations, and biases. For example, believing that a single anecdotal report proves a universal truth disregards the larger body of evidence needed for such a claim. A belief that exceeds the evidence can lead one down a path of overconfidence in unsubstantiated ideas, which in turn distorts judgment and undermines critical thinking. If we allow beliefs to exceed evidence without challenge, we fail to uphold the standards of intellectual rigor that are foundational to truth-seeking.

Rational Belief as Accountability to Evidence

One of the strengths of the proportionality principle is that it holds individuals accountable to the objective weight of evidence rather than subjective biases or desires. Rational belief demands a commitment to update or adjust one’s beliefs in light of new or better evidence. When belief aligns with evidence, it remains flexible and open to revision, reflecting a responsible intellectual stance. In contrast, belief that ignores or exceeds evidence is likely to be resistant to change, even when evidence contradicts it. By committing to proportionality, we embrace a growth mindset that values truth over dogmatism, fostering a worldview that evolves as our understanding deepens.

Intellectual Integrity and Rational Belief

Aligning belief with evidence demonstrates intellectual integrity, which is the commitment to pursue truth through honest engagement with reality. This integrity requires that we do not overstate our beliefs or claim certainty where uncertainty prevails. Believing exactly to the degree that evidence supports is a mark of intellectual honesty because it resists the lure of unfounded certainty. Rational belief, in this sense, respects the limitations of what we know, avoiding the pitfalls of wishful thinking or confirmation bias. By adhering to the proportionality principle, we safeguard against the tendency to inflate our beliefs beyond what the facts justify.

Rational Belief in Everyday Decision-Making

The principle of aligning belief with evidence is not only abstractly rational but also practically beneficial. In everyday decision-making—whether in finance, health, relationships, or politics—beliefs that are proportionate to evidence lead to better decisions and more accurate judgments. For instance, investing in a company based solely on rumors without thorough research would be irrational because it places faith beyond what is evidenced. By basing beliefs and actions on verified information, individuals avoid making decisions that are likely to result in disappointment, risk, or harm. The principle of proportionality thus applies across contexts, making it universally valuable.

Responding to Objections: The Role of Faith and Intuition

Some may argue that faith or intuition can justify belief beyond the evidence, particularly in personal or spiritual contexts. However, while faith and intuition may offer personal comfort, they do not provide objective justification for holding a belief with conviction beyond what evidence supports. Rational belief does not dismiss the role of intuition but asks that intuition be tempered by evidence to avoid self-deception. When intuition aligns with evidence, it can reinforce rational belief; when it diverges, it becomes a personal sentiment rather than a basis for justified belief. In cases of limited evidence, the most rational stance is often suspended judgment or tentative belief, rather than an unwavering stance that exceeds what is known.

Conclusion: Rational Belief as a Foundation for Truth-Seeking

The notion that rational belief is a degree of belief that matches the degree of relevant evidence provides a powerful framework for truth-seeking and critical thinking. By demanding that belief align with evidence, we uphold a standard of intellectual responsibility that respects the boundaries of knowledge. Such proportionality prevents the pitfalls of overconfidence, promotes accountability, and embodies a commitment to intellectual integrity. A world in which beliefs consistently matched the degree of evidence would be one where truth, reason, and understanding flourish, leading us closer to a well-reasoned and coherent worldview.

Note that doubt can also be irrational if its degree does not map to the degree of the available evidence. This mapping of the degree of belief to the degree of the relevant evidence is often called a credence. The skill of rationally positioning one’s degree of belief to the degree of evidence one has available to them can be called credencing and is a very valuable skill to develop. An excellent book relevant to this notion is called Thinking in Bets. I think you’ll find it both entertaining and useful in your pursuit of a rational mind.

Doubt and belief function as two sides of the same epistemic coin, representing the gradient by which we assess knowledge and evidence. Just as a glass can be seen as part-full or part-empty, doubt and belief exist along a spectrum where one fills the space that the other leaves open. This epistemic gradient illustrates that belief is not a binary state but rather an intrinsically gradual stance that shifts with the fraction of evidence supporting it. The more evidence we gather, the more belief occupies the gradient, reducing doubt proportionally. Thus, belief and doubt are complementary terms, each expressing our evolving position on knowledge, shaped by the evidence we hold.

Syllogism

- Premise 1: Rationality of a belief is maximized when the degree of belief precisely equals the degree of relevant evidence.

- Premise 2: The degree of rationality of a belief decreases in direct proportion to the absolute deviation between the degree of belief and the degree of evidence.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a belief is rational to the extent that the degree of belief aligns with the degree of evidence, and irrational to the extent that it deviates from this alignment.

Symbolic Logic

Let:

represent the degree of belief in

represent the degree of evidence for

represent the degree of rationality of belief in

, where

(with

representing maximum rationality and

representing complete irrationality)

as a proportionality constant to normalize the scale of rationality

Formal Representation

- Premise 1 (Maximum Rationality):

if and only if

(The degree of rationality of belief inis maximized when the degree of belief equals the degree of evidence.)

- Premise 2 (Proportional Deviation):

(The degree of rationality of belief indecreases in proportion to the absolute deviation between the degree of belief and the degree of evidence.)

- Conclusion:

As,

(indicating maximum rationality). Conversely, as

increases,

approaches 0, indicating increasing irrationality.

This formulation rigorously quantifies the relationship between the degree of rationality and the alignment between belief and evidence.

The Inconsistency of Faith:

— Unveiling the Tell of Irrationality in Religious Leadership

Religious belief has long been a cornerstone of human society, providing moral guidance, community cohesion, and answers to life’s profound questions. Central to this belief system is the relationship between faith and evidence—a delicate balance that religious leaders navigate as they guide their congregations. However, an intriguing inconsistency emerges when these leaders condemn individuals who adjust their beliefs in proportion to evidence, yet celebrate those whose faith exceeds the available evidence due to emotional appeal or the allure of promised rewards. This disparity reveals a “tell” of irrationality within religious leadership, highlighting a preference for unwavering belief over critical examination.

The Nature of Belief and Evidence

Belief, in its purest form, is an acceptance that something exists or is true, particularly without proof. Evidence, conversely, comprises the facts or information indicating whether a belief is valid. In rational discourse, beliefs are ideally proportioned to the degree of evidence supporting them—a principle championed by philosophers and scientists alike. This approach fosters critical thinking and adaptability, allowing individuals to revise their understanding as new information emerges.

Encouraging Unquestioning Faith in the Young

Religious leaders often nurture a deep-seated faith in children, emphasizing stories and promises that resonate emotionally. The beauty of these narratives—the promise of eternal life, unconditional love, and a moral universe—can lead young minds to embrace beliefs that surpass the supporting evidence. This is typically encouraged, as it fosters a strong foundational faith that can endure life’s challenges. The innocence and openness of children make them receptive to accepting doctrines without skepticism, which religious communities might view as a virtue.

Condemnation of Evidence-Based Doubt

In stark contrast, when individuals, particularly adults, begin to question their faith and adjust their beliefs based on empirical evidence or logical reasoning, they may face criticism or ostracism from religious leaders. Doubt is often portrayed not as a natural and healthy part of intellectual growth but as a moral failing or a lack of faith. This condemnation discourages critical inquiry and reinforces a culture where belief is valued over understanding.

The Tell of Irrationality: Inconsistency in Approach

This inconsistency—the celebration of belief without evidence in some cases and the denunciation of evidence-based doubt in others—serves as a tell of irrationality within religious leadership. It indicates a departure from a consistent application of principles regarding belief and evidence. If the ultimate goal were the pursuit of truth, then both excessive belief without evidence and skepticism leading to adjusted beliefs would be met with understanding and guidance. Instead, the preferential treatment suggests an underlying motive to preserve doctrine and authority over fostering genuine understanding.

Psychological and Social Underpinnings

Several factors contribute to this irrational stance. Psychologically, faith can serve as a coping mechanism against existential uncertainties, and challenging it may induce anxiety or fear. Socially, religious institutions often rely on the cohesion of shared beliefs to maintain community structure and influence. Encouraging unquestioning belief strengthens group identity, while skepticism threatens the homogeneity that leaders might find essential for maintaining control and unity.

The Importance of Proportioning Belief to Evidence

Adhering to beliefs that align with evidence is crucial for personal growth and societal progress. It promotes open-mindedness, adaptability, and a deeper understanding of the world. When individuals are free to question and adjust their beliefs, they contribute to a culture of innovation and ethical reasoning. Suppressing this process can lead to stagnation and hinder the development of critical thinking skills.

Conclusion: Embracing Rationality in Faith

The inconsistency exhibited by religious leaders—condemning evidence-based doubt while endorsing belief without evidence—highlights a fundamental irrationality. Recognizing this tell is essential for individuals seeking a balanced and authentic spiritual journey. By embracing a rational approach to faith, where beliefs are proportioned to evidence, religious communities can foster an environment of genuine understanding and respect for individual intellectual growth. This shift could lead to a more profound and resilient faith, one that withstands scrutiny and evolves with expanding knowledge.

In reevaluating the dynamics of belief and evidence within religious contexts, both leaders and followers have the opportunity to bridge the gap between faith and reason. This reconciliation not only strengthens personal convictions but also enhances the collective wisdom of the community, paving the way for a more enlightened and harmonious society.

Corresponding Syllogisms and Symbolic Logic

Definitions

Let us define the following predicates:

:

proportions their degree of belief to the degree of the evidence (rational belief).

:

holds a degree of belief that exceeds the degree of the evidence due to emotional appeal (irrational belief).

: Religious leaders condemn

.

:

is a child.

:

is an adult.

: Religious leaders.

:

is acting rationally.

:

is acting irrationally.

Syllogism 1: Condemnation of Rational Doubt

Premise 1:

Religious leaders condemn adults who proportion their belief to the evidence.

Premise 2:

Proportioning belief to the evidence is rational behavior.

Conclusion:

Religious leaders condemn rational adults.

Syllogism 2: Acceptance of Irrational Belief in Children

Premise 1:

Religious leaders do not condemn children whose belief exceeds the evidence due to emotional appeal.

Premise 2:

Holding beliefs that exceed the evidence due to emotional appeal is irrational behavior.

Conclusion:

Religious leaders do not condemn irrational children.

Syllogism 3: Inconsistency of Religious Leaders

Premise 1:

Condemning rational behavior while accepting irrational behavior is inconsistent and irrational.

Premise 2:

Religious leaders condemn rational adults and do not condemn irrational children.

Conclusion:

Religious leaders are acting inconsistently and irrationally.

Summary of the Argument

Rationality Principle: Rational individuals proportion their beliefs to the evidence.

Irrationality Principle:

Individuals who believe beyond the evidence due to emotional appeal are acting irrationally.

Religious Leaders’ Actions:

Condemn rational adults:

Do not condemn irrational children:

Inference of Irrationality:

Accepting irrationality and condemning rationality indicates inconsistency.

Conclusion

The formalization above demonstrates that religious leaders:

- Condemn rational behavior in adults who doubt due to lack of evidence.

- Do not condemn irrational behavior in children whose belief exceeds the evidence because of emotional appeals.

This inconsistency suggests that the religious leaders themselves are acting irrationally. By favoring unwavering belief over a proportionate response to evidence, they reveal a preference for belief without scrutiny, which undermines rational discourse and critical thinking.

Leave a comment