Consider the Following:

Summary: Biblical prophecies frequently cited by Christians, such as those about Tyre’s destruction, the “suffering servant,” and the signs of the end times, often lack the specificity and clarity expected of divine predictions, allowing for broad and shifting interpretations across time. This ambiguity raises doubts about their intended role as evidence for God’s existence, suggesting instead that they may be human constructs shaped to fit varying historical contexts.

Imagine your friend Tom claims his parents, long before he was born, astonishingly prophesied that he would 1) get a haircut before starting at Harvard, 2) marry a French woman, and 3) work as a doctor in Chicago. These specific events, according to Tom, confirm his parents’ psychic abilities. Intrigued, you ask to see the original prophecies.

The “prophecies” are vague:

- DAD: “I envision our clean-cut kids attending prestigious universities.”

- MOM: “Yes, we’ll have a son with a well-paying job in a big city by a large lake, with a European wife, perhaps.”

None of this confirms Tom’s claim. Much of it is ambiguous, could fit any of Tom’s siblings, or could simply be molded to fit Tom’s life choices. Should we conclude these are true prophecies?

This analogy provides guidelines for evaluating any prophecy’s credibility:

- Specificity: Is the event uniquely tied to a time and place, or does it vaguely echo past events, making it open to reinterpretation?

- Comparative Precision: Does it share the same vague specificity as prophecies in other religions we dismiss?

- Literature Volume: Is it part of an extensive text, making a coincidental “match” more probable?

- Fabrication Potential: Were the events truly spontaneous, or could followers, aware of the prophecy, fabricate or manipulate events?

Biblical Examples and Issues

Consider Isaiah’s prophecy (Isaiah 7), where the virgin birth prophecy (Isaiah 7:14) is often cited regarding Jesus, despite context suggesting it only applied to King Ahaz’s era. Similarly, Quran 54:1’s reference to a “splitting moon” is interpreted by some Muslims as foretelling the 1969 moon landing. Revelation 9:7-10 is even cited as predicting helicopter gunships in the Kuwait War.

Probability of Vague Fulfillment: With thousands of biblical verses, coincidental “fulfillment” becomes almost inevitable. Matthew 13:14 claims Isaiah 6:9’s prophecy (“You will be ever hearing but never understanding”) is fulfilled in people ignoring Jesus’ parables, a universal human experience rather than a divine prediction.

Human Influence in “Fulfillments”: The triumphal entry into Jerusalem, where Jesus rides a donkey (Zechariah 9:9), would have been simple to arrange by New Testament authors familiar with Zechariah’s text. Likewise, the re-establishment of Israel cannot be attributed solely to prophecy given that powerful actors knew of and pursued it.

Additional Examples of Vague Prophecies

Vague “Prophecy” List

1. Ezekiel’s Prophecy of Tyre’s Destruction (Ezekiel 26:3-14)

Ezekiel predicts that Tyre will be destroyed, “never to be rebuilt,” by Nebuchadnezzar. While Nebuchadnezzar did invade Tyre, he was unable to fully conquer or destroy it, and Tyre continued to exist for centuries afterward, even thriving under the Greeks. This prophecy is often cited as fulfilled, but its vagueness in scope and the failure to eradicate Tyre entirely raises questions. Could it be argued as fulfilled only because parts of it align loosely with historical events?

2. The Sign of the Fig Tree (Matthew 24:32-34)

Jesus refers to the fig tree’s budding as a sign of “the end,” declaring, “this generation will certainly not pass away until all these things have happened.” Many interpret “this generation” to mean Jesus’ contemporaries, expecting the end to come within their lifetime. Since this did not happen, later interpretations reframe “generation” to mean the “generation witnessing Israel’s rebirth” in 1948, or even a broader epoch. Does this prophecy lack clarity because “this generation” is ambiguously defined?

3. Gog and Magog in Revelation 20:8 and Ezekiel 38-39

Revelation and Ezekiel both refer to Gog and Magog as future enemies of God’s people, but the historical or geographical identities of these names are unclear. Over centuries, different figures have been called “Gog and Magog,” from the Huns to the USSR, making the prophecy adaptable to nearly any threat. Is this ambiguity intentional, allowing each generation to apply the prophecy to its own perceived adversaries?

4. Psalm 22 and Jesus’ Crucifixion

Psalm 22, especially verses like “They pierced my hands and my feet,” is often cited as a prophecy of Jesus’ crucifixion. However, the original Hebrew text is debated, with some translations rendering it as “like a lion, my hands and my feet.” The psalm’s vivid language and general anguish could also describe many sufferings experienced by others. Could this passage be more metaphorical than prophetic, adapted later to fit Jesus’ story?

5. The “Prince to Come” and the “70 Weeks” of Daniel (Daniel 9:24-27)

This passage is highly interpretive, with the “anointed one” and the “prince to come” often understood as Jesus or an Antichrist figure. Calculations of the “70 weeks” are varied, with some interpreting them as weeks of years, others as symbolic periods. Different readers place these events centuries apart, while the “end times” hinted at remain ever-shifting. Does this prophecy’s flexibility make it prone to reinterpretation based on historical or modern events?

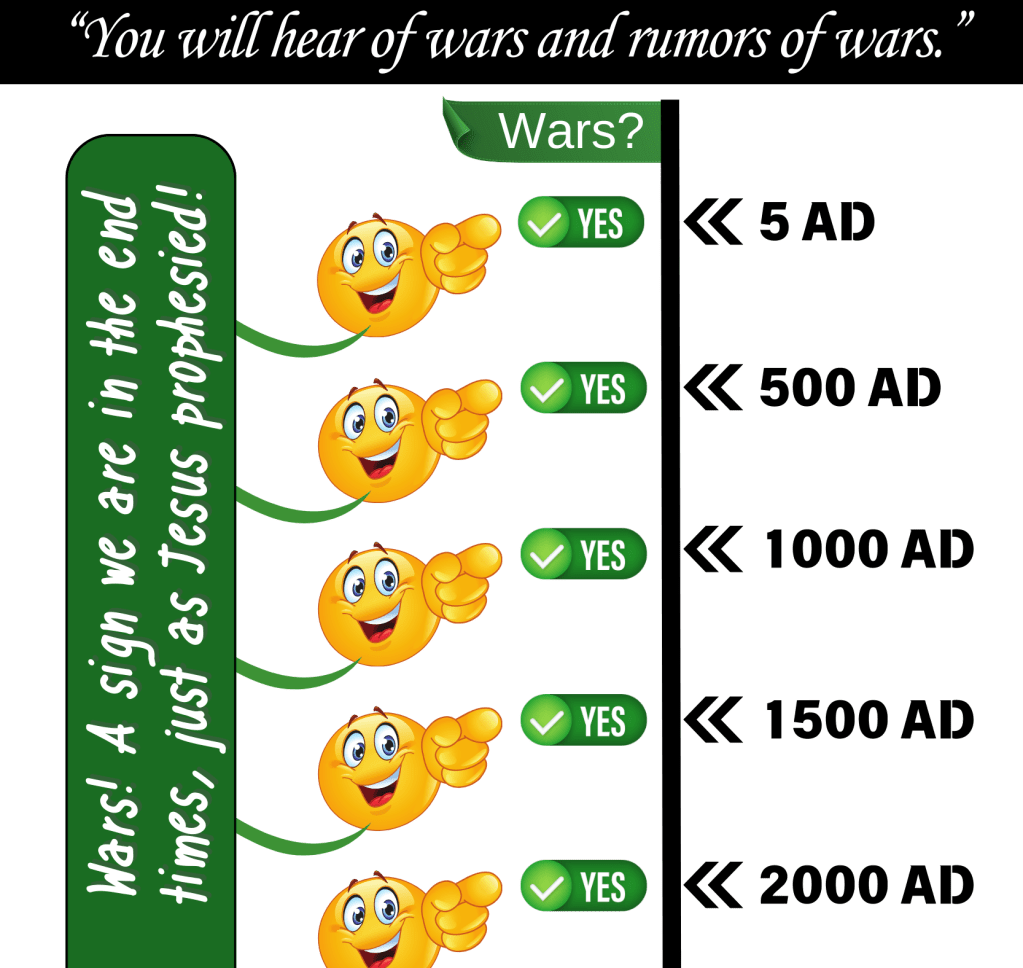

6. The End of the World and Wars (Matthew 24:6-8)

Jesus foretells that “You will hear of wars and rumors of wars…there will be famines and earthquakes in various places.” However, wars, famines, and natural disasters have been constants throughout human history, making this statement broad and universally applicable. Some Christians cite recent global conflicts as signs of the prophecy being fulfilled, yet these types of events are perpetually recurring. Does the ongoing nature of such events dilute their predictive value?

7. Isaiah 53 and the Suffering Servant

Isaiah 53 describes a “suffering servant” who “was pierced for our transgressions.” This is often seen as a prediction of Jesus’ sacrificial death, though some scholars argue the passage refers to Israel collectively or a different figure. The identity of the servant is never explicitly stated as “Messiah” or “Jesus,” making it possible to reinterpret the text. Is the lack of a clear identity in this prophecy what allows its application to various figures?

8. “The Two Witnesses” in Revelation (Revelation 11:3-12)

Revelation’s prophecy of two witnesses who “prophesy for 1,260 days” and are killed, then resurrected, has been applied to different historical and modern figures, from Moses and Elijah to hypothetical end-time prophets. The absence of specific details—such as their identities, timeline, or location—permits multiple interpretations across eras. Could the symbolism here suggest a deliberately enigmatic prophecy that offers no clear expectation?

Postdiction in Biblical Prophecies

Postdiction—the act of interpreting past events as if they were foretold—often appears in religious texts, where events are reinterpreted or adjusted to align with previously written prophecies. This process can give the impression of fulfilled prophecy when, in fact, it may reflect human efforts to match existing narratives to current circumstances. In the Bible, many scholars argue that postdiction is at play in prophecies that appear suspiciously accurate about past events, or which were likely adapted to fit historical occurrences long after the fact.

One prominent example is the prophecy regarding King Cyrus of Persia in Isaiah 45:1, where Cyrus is named as a future restorer of Israel, who would rebuild Jerusalem and free the Jewish people from exile. While this appears as a strikingly accurate prediction, scholars point out that the Book of Isaiah was likely edited or completed after the Persian king’s actions, allowing editors to incorporate Cyrus’s identity into the narrative. This is widely considered a postdictive enhancement meant to show God’s hand in the unfolding of history, yet it loses its miraculous status if the prophecy was modified after the events had already occurred.

Another example is found in Daniel 11, where the “king of the north” and “king of the south” contend through a detailed series of wars and alliances that closely resemble the conflicts between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties. This passage is thought to align so precisely with events from the second century BCE that many scholars believe it reflects the era’s historical record rather than a divine foretelling. The “prophecy” abruptly ends before accurately predicting events beyond that time, suggesting it was written after the events it describes and ceased when it reached future uncertainties.

Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection narratives also include elements that might reflect postdictive interpretations. Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53 are often viewed as foretelling aspects of Jesus’ suffering and sacrifice, yet many of these passages appear as literary or theological adaptations, shaped to mirror well-known Old Testament texts. This approach would allow early Christian writers to present Jesus’ life as fulfilling Jewish prophecy, using known scriptures to give deeper significance to Jesus’ actions and experiences. In particular, Jesus riding a donkey into Jerusalem (Zechariah 9:9) could have been purposefully enacted or interpreted to fulfill this “prophecy,” reflecting postdictive storytelling.

In these cases, postdiction raises questions about whether such prophecies are indeed supernatural predictions or retrospective literary constructions. This interpretive approach reinforces the belief that rather than proving divine intervention, these passages may highlight the human tendency to find patterns and fulfillments after the fact, blending religious narrative with historical retrospection.

Emotional and Psychological Motivations Behind Possible Postdiction in the Gospels

The claim that the Gospel writers had no reason to lie ignores the powerful emotional and psychological pressures that can lead individuals to reshape truth without conscious deceit. The Gospel authors were not detached historians—they were emotionally invested followers attempting to make sense of the humiliating death of someone they revered. Faced with the cognitive dissonance of a failed messianic expectation, the trauma of public execution, and the collapse of their apocalyptic hopes, they had every reason to reinterpret past scriptures in a way that rescued meaning from despair. Their loyalty to Jesus, their need to redeem personal sacrifices, and their longing to maintain purpose and coherence in their lives gave rise to postdiction—not as malicious fabrication, but as emotionally driven storytelling. In this light, the notion that they “had no motive to lie” oversimplifies human psychology and underestimates the complex interplay between grief, hope, and narrative reconstruction.

Emotional Momentum and the Irreversibility of Belief

Once someone had accepted Jesus as the Messiah, the emotional investment only deepened over time. Backtracking would mean undoing identity, community, and hope. Postdiction allowed believers to double down emotionally without admitting they had ever misunderstood what kind of Messiah he was.

Disillusionment and the Need to Salvage Hope

Jesus’ execution shattered the expectations of those who believed he would overthrow Roman rule and establish God’s kingdom on earth. Faced with the collapse of that hope, the psychological need to reinterpret the defeat as a higher kind of victory became overwhelming. Postdiction allowed them to reframe suffering and death not as tragic endings, but as sacred necessities written into history all along.

Grief Sublimated into Glorification

For those who walked with Jesus, ate with him, and saw him as a friend, mentor, and possibly even divine, the emotional shock of his humiliating public death would have been traumatic. Postdiction became a mechanism for mourning with meaning—transforming the unbearable into the ordained, sorrow into salvation.

Loyalty to a Fallen Leader

A deep sense of personal loyalty likely motivated early followers to protect Jesus’ reputation. If he was misunderstood, rejected, and executed, then the story must be retold in a way that vindicates him. Finding ancient scriptures that could be stretched to mirror his life was not just rhetorical strategy—it was emotional defense against the idea that he failed.

Cognitive Dissonance and the Urge to Resolve It

When reality contradicts expectations, the mind experiences discomfort. Jesus’ death, and the absence of a visible kingdom, created severe dissonance. Recasting the events of his life as “fulfillments” of prophecy offered an elegant solution: he did succeed—just not in the way we thought. This form of retroactive storytelling soothed internal tension.

The Shame of Being Wrong—and the Human Aversion to It

Many early Christians had likely made public declarations of Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah. When he died and nothing changed politically, the social embarrassment and internal humiliation would have been intense. Rather than admit error, postdiction offered an emotionally satisfying escape hatch: We were right all along—we just didn’t yet understand how.

The Need to Redeem Suffering

Watching a beloved teacher suffer and die, especially in an era where divine favor was linked to outward success, would have seemed like a catastrophic contradiction. The emotional drive to elevate suffering into sacred purpose fueled the search for scriptural parallels that could reframe brutality as fulfillment.

Longing for Control in a Chaotic World

Postdiction gave early believers a sense that nothing had gone wrong, that events were not spinning out of control, but rather unfolding precisely as God had planned. In a turbulent time of imperial domination, famine, and persecution, this was emotionally stabilizing.

Fear of Rejection by Broader Jewish Communities

The early Jesus movement was still situated within the Jewish world. As they drifted into heresy in the eyes of traditionalists, postdiction allowed them to emotionally validate themselves as true heirs of the Hebrew faith by rooting their story in old texts. They weren’t inventing something new; they were discovering what had been hidden all along.

The Need to Rescue the Meaning of One’s Life Investment

Some followers had given up families, jobs, and reputations to follow Jesus. His death without an earthly triumph risked rendering all of that meaningless. Postdiction was a way to protect the personal sacrifices they’d made by showing that their suffering was part of a divine narrative.

The Romanticization of the Past Under the Weight of the Present

When the future becomes uncertain or bleak, the past is often retold in elevated terms. The Gospel writers were likely under emotional pressure to look back on Jesus’ life not just with affection, but with cosmic significance, reading grandeur and destiny into moments that might have otherwise seemed mundane.

Desire to Belong to a Bigger Story

Humans crave belonging and purpose. By linking Jesus’ life to ancient scriptures, early Christians cast themselves not as fringe radicals following a failed prophet, but as participants in the grand, unfolding drama of redemption. This narrative gave them identity, dignity, and courage in the face of persecution.

The Power of Collective Emotional Reinforcement

As stories were shared and reshaped in tightly-knit communities, a kind of emotional contagion took hold. Those who doubted may have felt pressured to see fulfillment where none existed, or to reinterpret events in the community’s favored way. Postdiction thus became both a personal and communal emotional necessity.

Reframing Trauma as Transcendence

Crucifixion was not just execution—it was shame, dishonor, and abandonment. For Jesus’ followers, the emotional drive to transform public humiliation into cosmic exaltation fueled their willingness to read his story through any Old Testament lens that could elevate his suffering into divine plan.

Fear of Death and the Need for Assurance

Postdiction didn’t just redeem Jesus’ death—it offered hope for their own. If scripture showed that Jesus’ suffering and resurrection were foretold, then their own suffering might also be meaningful. This emotional need for eternal assurance gave fuel to prophetic re-readings that transformed pain into pathway.

See also:

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Vague Prophecy Section

Argument 1: The Ambiguity of Prophecies Undermines Their Predictive Value

- Premise 1: For a prophecy to serve as a clear indicator of divine origin, it must be specific and unmistakable in its predictions.

- Premise 2: Many biblical prophecies, such as those about Tyre’s destruction and wars and disasters, are broad and open to interpretation, making them universally applicable across various contexts.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the ambiguity of these prophecies undermines their value as reliable indicators of divine foresight.

Argument 2: The Fig Tree Prophecy and Flexible Interpretations

- Premise 1: In Matthew 24, Jesus states that “this generation” will not pass until certain signs are fulfilled, referring to the parable of the fig tree as an indication of the end times.

- Premise 2: Interpretations of “this generation” have shifted to fit different historical periods, showing a flexibility that allows the prophecy to remain relevant regardless of when it is applied.

- Conclusion: Thus, the vagueness of this prophecy allows it to be interpreted in various ways, weakening its credibility as a specific divine prediction.

Argument 3: Psalm 22 and the Suffering Servant as Broad Metaphors

- Premise 1: Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53 are often cited as predictions of Jesus’ suffering, yet the language in these passages is metaphorical and could describe various types of suffering experienced by many individuals.

- Premise 2: The application of these passages to Jesus’ life relies on interpretive readings that may not align with the original intent or context.

- Conclusion: Consequently, these passages’ broad language and metaphorical elements make them unlikely to be specific prophecies about Jesus, suggesting a general description rather than a divine prediction.

Argument 4: General Events in Matthew 24 Lack Predictive Value

- Premise 1: In Matthew 24:6-8, Jesus mentions wars, famines, and earthquakes as signs of the end times, which are common events throughout history.

- Premise 2: Such events are perpetually occurring, allowing this prophecy to be continuously cited as relevant, regardless of the time period.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the prophecy’s focus on universal phenomena undermines its credibility as a unique divine forecast, as it lacks specific predictive value.

Postdiction Section

Argument 5: Postdiction Alters Perceptions of Divine Prophecy

- Premise 1: Postdiction occurs when past events are interpreted or edited into a narrative to appear as if they were predicted.

- Premise 2: In the Bible, several prophecies align suspiciously well with historical events, suggesting they may have been retrospectively adapted to match outcomes.

- Conclusion: Therefore, prophecies presented as divine predictions in the Bible may be products of postdictive adjustments rather than genuine foresight.

Argument 6: The Detailed Predictions in Daniel 11 as Historical Record Rather than Prophecy

- Premise 1: Daniel 11 describes conflicts between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties in a highly detailed manner, closely resembling historical events of the second century BCE.

- Premise 2: This section ends before accurately predicting events beyond that time, suggesting it was written with knowledge of past events and halted when reaching future uncertainties.

- Conclusion: Consequently, the detailed “prophecies” in Daniel 11 appear to be postdictive historical accounts rather than divinely inspired foresight.

Argument 7: Jesus’ Crucifixion Narratives as Postdictive Interpretations of Old Testament Texts

- Premise 1: Narratives of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection mirror Old Testament passages, particularly Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53, which Christians often view as prophecy.

- Premise 2: Scholars argue that these passages were selectively adapted to match Jesus’ life, enhancing connections between Old Testament texts and New Testament events.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the parallels between Jesus’ actions and Old Testament prophecies are likely cases of postdictive literary construction.

Argument 8: Postdiction Questions the Validity of Prophecies as Divine Predictions

- Premise 1: Many biblical prophecies, such as those about Cyrus, Daniel’s visions, and Jesus’ crucifixion, align with historical events but may have been shaped after the events occurred.

- Premise 2: This pattern suggests a human tendency to seek retrospective patterning rather than genuine predictive prophecy.

- Conclusion: As a result, the presence of postdictive interpretations in biblical prophecies undermines their reliability as evidence of divine intervention.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Analyzing the Nature of Biblical Prophecy

CHRIS: I find the prophecies in the Bible to be one of the strongest arguments for God’s existence. They offer specific predictions that could only have come from a divine mind.

CLARUS: I understand why you’d think that, but many of these prophecies rely on postdiction—interpreting past events as if they were predicted. Take the prophecy of Cyrus in Isaiah; it names him explicitly, but scholars believe it may have been written or edited after Cyrus’s actions, which means it might not be a true prediction.

CHRIS: But if Cyrus was indeed prophesied, then it suggests divine foreknowledge. How could that be mere coincidence?

CLARUS: That’s where postdictive enhancement comes in. If the text was completed after Cyrus, editors could easily include his name to make it appear as a fulfilled prophecy. It’s similar to the prophecies in Daniel 11, which align precisely with historical events up to a point but stop before reaching events in the distant future. This pattern suggests they were written after the fact rather than foreseen.

CHRIS: But what about Psalm 22 and Isaiah 53? These texts are seen as predictions of Jesus’ suffering and crucifixion, written long before his life.

CLARUS: Yet those texts are filled with metaphorical language and general descriptions of suffering. The “suffering servant” could represent Israel, an unknown figure, or anyone experiencing hardship. This vagueness allows later writers to link it to Jesus, but the connection is interpretative, not explicit.

CHRIS: So, you’re saying the Bible’s prophecies are too ambiguous?

CLARUS: Exactly. If these were truly divine predictions, I’d expect them to be specific and unambiguous, not open to multiple interpretations. For instance, Jesus’ prophecy of the end times in Matthew 24 includes things like wars and famines—events that happen regularly. People always interpret these as signs, but such generalities are applicable in any era, which makes the prophecy essentially self-fulfilling.

CHRIS: But isn’t that part of the beauty of prophecy? It’s flexible, allowing us to see God’s work throughout different generations.

CLARUS: Flexibility doesn’t support the idea of divine prophecy; it weakens it. If the Bible’s prophecies can be reinterpreted to fit any context, they don’t provide solid evidence of a specific divine plan. For example, the fig tree prophecy mentions “this generation” without clarifying whether it meant Jesus’ contemporaries or some future group. This ambiguity keeps it relevant but undermines its reliability as proof of divine foreknowledge.

CHRIS: I still believe in the power of these prophecies. Doesn’t their consistency over time count for something?

CLARUS: Not when that consistency comes from their ability to be adapted. Look at Gog and Magog in Revelation—they’ve been applied to countless enemies throughout history. If a prophecy can fit any situation, it stops being a prophecy and becomes more of a symbol that each generation applies as they see fit.

CHRIS: I see your point about interpretation, but I believe that God’s intent might be beyond our understanding. Maybe the ambiguity is there for a reason.

CLARUS: It could be, but if we’re using prophecy as proof of a divine being, then that ambiguity works against it. If these prophecies were clearer and uniquely specific, they’d be much stronger as evidence. Instead, they seem to follow human patterns of postdiction and flexibility, fitting past events rather than truly foretelling the future.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Weather Forecast

Imagine a weather forecast that simply says, “There will be rain at some point and sunshine at other times over the next year.” This prediction will inevitably be “fulfilled” at some point due to its broad and unspecific language—rain and sunshine are regular occurrences. Similarly, when biblical prophecies mention common events like wars or famines, they are bound to feel fulfilled since such occurrences are universal and timeless. The lack of specificity diminishes their value as true forecasts and leaves them open to interpretation in any context.

Analogy 2: The Fortune Cookie

Consider a fortune cookie that reads, “A great opportunity will come your way soon.” Because of its vagueness, this “prediction” could apply to almost anyone at any time and can be easily interpreted to fit nearly any situation—whether it’s a new job, a friendship, or a personal project. In this way, the fortune cookie’s ambiguity resembles many biblical prophecies that can be adapted to fit various scenarios across generations, making them seem fulfilled without offering concrete predictive power.

Analogy 3: The Historical “Prediction” in a Biography

Imagine a biography of a famous figure that claims they were destined to have an impactful career in politics, with a promise of “changing the world.” If this biography were written after their rise to fame, the “prediction” could simply be postdiction—information known to the author that was retroactively framed as prophetic. This process reflects the postdictive enhancement found in some biblical texts, where details may have been added or shaped after events occurred, giving the impression of fulfilled prophecy when, in fact, the events were already known to the author.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. The Ambiguity May Reflect a Divine Intention to Foster Faith

Some theologians argue that ambiguity in prophecy is not a flaw but an intentional design by God to encourage faith rather than reliance on concrete proof. They suggest that open-ended prophecies are meant to inspire reflection and personal interpretation, allowing each generation to seek God’s guidance and discernment rather than demand certainty. From this perspective, the vagueness enhances rather than detracts from the prophecy’s purpose, aligning with a divine desire for believers to exercise faith.

2. Prophetic Fulfillments Are Validated by Historical Events, Not Fabricated

Theologians who support the authenticity of biblical prophecy often point out that many historical fulfillments of prophecy, such as the fall of certain cities or the exile and return of the Jewish people, are confirmed by secular history. They argue that accusations of postdiction undermine the textual integrity of scripture and ignore evidence of prophecies being recorded before the events occurred. In cases like Cyrus’s role in Isaiah, they maintain that these prophecies were genuinely predictive, not retroactively adapted to fit historical outcomes.

3. Prophecies Require Interpretation Due to Their Symbolic Nature

Some theologians assert that prophecies are inherently symbolic and require interpretation because they deal with spiritual truths that can’t always be conveyed through literal language. Just as parables are used to reveal deeper meanings, so too are prophecies meant to be analyzed, understood, and applied across time. In this view, the symbolism and metaphors are tools to convey divine messages that transcend specific events, offering timeless wisdom rather than direct predictions.

4. Many Prophecies Are Surprisingly Specific and Detailed

Theologians often counter claims of ambiguity by citing examples of detailed biblical prophecies that appear clear and precise. For instance, they may reference prophecies concerning Jesus’ lineage, his birth in Bethlehem, and specific events surrounding his crucifixion, which are seen as uniquely fulfilled by him. They argue that these precise elements demonstrate an intentional design that goes beyond general predictions, showcasing God’s sovereignty and foresight.

5. Repeated Patterns Reflect God’s Consistent Presence, Not Ambiguity

Theologians sometimes argue that recurring patterns in prophecy are a sign of God’s active involvement in history rather than evidence of ambiguous predictions. They see events like wars, famines, and persecutions as repeated manifestations of spiritual conflict and divine purpose. In this view, the patterns validate God’s constant presence and unchanging nature, reminding believers of ongoing spiritual truths rather than attempting to predict isolated historical events.

Counter-Responses

1. Faith-Based Ambiguity Undermines Predictive Value

While ambiguity may indeed allow believers to exercise faith, it simultaneously undermines the predictive value that distinguishes prophecy from mere generality. If prophecy’s purpose is to affirm divine foresight, then ambiguous predictions that lack specificity resemble open-ended statements more than divine messages. A prophecy requiring interpretation to fit varying situations across generations doesn’t serve as reliable evidence of divine intent and becomes nearly indistinguishable from statements that could be self-fulfilling or retrospectively applied.

2. Historical Validation Does Not Preclude Postdiction

While it is true that some biblical events align with historical records, this does not necessarily confirm them as fulfilled prophecies rather than postdictions. The presence of prophecies that are strikingly accurate in retrospect, such as those in Daniel 11 and Isaiah 45, is often what raises scholarly suspicion about potential retroactive editing. Historical alignment alone cannot validate prophecy if the texts themselves may have been adapted after the events, thus making historical validation insufficient without clear textual evidence that the prophecy preceded the events.

3. Symbolism Dilutes Predictive Claims

The claim that symbolic interpretations are necessary to understand prophecy actually works against the concept of prophecy as a predictive tool. Symbolic or metaphorical language allows almost any event to be interpreted as fulfillment, thereby reducing prophecy to a form of flexible storytelling rather than a reliable forecast. If prophecies require interpretation across eras, they lose their specificity and credibility, opening the door for selective readings that can be molded to fit preconceived religious narratives rather than reflecting a precise divine prediction.

4. Specificity in Prophecies is Often Selectively Applied

While some biblical prophecies may seem specific, closer examination reveals that interpretive bias plays a significant role in these readings. For example, the New Testament authors’ familiarity with Old Testament texts like Psalm 22 allowed them to shape Jesus’ narrative to align with perceived prophetic details. Furthermore, the few prophecies that appear specific are exceptions, while the majority remain vague and adaptable. This selective application of specificity fails to establish divine intent when most prophecies are broadly interpretable.

5. Repeated Patterns Reflect Human Experience, Not Divine Consistency

Theologians may interpret repeated patterns in prophecy as proof of God’s consistency, but such patterns can also reflect universal human experiences, such as war, natural disasters, and conflict. These themes are common across religious and cultural texts, making them more indicative of shared human struggles than of a specific divine message. By ascribing universal occurrences to divine intention, theology risks mistaking general experiences for prophecy, thereby weakening the argument for divine specificity and predictive value.

Clarifications

The Role of Postdiction in Apostolic Writings

The apostles’ deep familiarity with the Old Testament provided them with a vast reservoir of prophecies, metaphors, and themes to draw upon, allowing them to retroactively frame events in Jesus’ life as fulfillments of ancient scripture. Many of the prophecies cited as fulfilled by Jesus—such as Psalm 22’s reference to suffering or Isaiah 53’s “suffering servant”—were well known to the apostles and early followers. Their knowledge of these texts made postdiction an easy choice, enabling them to craft narratives that aligned with prophetic expectations. Rather than serving as pre-event predictions, many of these passages could be fitted retrospectively to Jesus’ experiences, giving the impression of fulfillment without requiring genuine foresight.

An unusual aspect of these accounts is the significant delay between the events of Jesus’ life and the time when the apostles began writing them down. Most New Testament writings were composed decades after the alleged resurrection. This delay is curious, particularly given the monumental nature of the resurrection claim—an event that, if true, would signify the ultimate divine intervention and foundational moment for a new faith. Today, if someone were to witness such an event, especially if it held the weight of becoming the Word of God, it is unlikely they would wait so long to record it. In an era of widespread literacy and quick information-sharing, even relatively ordinary events are often documented promptly to preserve details and authenticity. This raises questions about why the apostles, who lived in a largely oral culture yet possessed basic literacy, would postpone documenting what they considered the most critical event in human history.

The time lapse also left room for embellishment, reinterpretation, and theological reflection, which can blur historical accuracy. Postdiction could thus serve as a narrative tool to integrate revered Old Testament passages into the life of Jesus, forming a cohesive story designed to fit long-held prophetic frameworks. This approach allowed early Christians to present Jesus as the expected Messiah, weaving together Jewish texts to legitimize their claims. However, the choice to wait decades to write such an account—and the apostles’ use of Old Testament knowledge to postdictively shape these narratives—suggests that the scriptural “fulfillments” might reflect interpretative storytelling more than literal fulfillment of prophecy.

“Unpacking the Prophecies: A Critical Examination of New Testament Claims of Old Testament Fulfillment in Jesus”

The claim that Jesus fulfilled Old Testament (OT) prophecies is central to New Testament (NT) theology, but some argue that NT writers stretched, misinterpreted, or manipulated OT texts to fit their narrative. Critics point to several instances where the connections between OT prophecies and their NT applications seem tenuous, contextually dubious, or outright problematic. Below, I’ll examine the most frequently cited examples of alleged “failures” or “fudges” by NT writers, providing a detailed analysis of each case. I’ll aim to be exhaustive, covering major examples, while grounding the discussion in the texts themselves, their historical context, and scholarly perspectives. The goal is to present a balanced view, acknowledging both the NT writers’ intentions and the criticisms leveled against them.

1. Matthew’s Use of Isaiah 7:14 – The Virgin Birth

Claim: Matthew 1:22-23 cites Isaiah 7:14 to argue that Jesus’ virgin birth fulfills the prophecy: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel.” Criticism:

- Contextual Misalignment: In its original context, Isaiah 7:14 addresses King Ahaz of Judah during a political crisis involving the Syro-Ephraimite War (circa 735 BCE). The “sign” of a child named Immanuel was likely meant to assure Ahaz that the threat from Israel and Aram would end soon—before the child reached a certain age (Isaiah 7:16). Many scholars argue the child was Isaiah’s own son or a royal heir, not a messianic figure centuries later.

- Translation Issue: The Hebrew word in Isaiah 7:14 is almah (young woman), which does not explicitly mean “virgin.” The Greek Septuagint (LXX), which Matthew likely used, translates it as parthenos (virgin), introducing a possible misinterpretation. Critics argue Matthew exploited this translation to align with the virgin birth narrative.

- Name Discrepancy: Jesus is never called “Immanuel” in the NT, raising questions about the prophecy’s direct fulfillment.

- Anachronism: Applying a prophecy tied to an immediate 8th-century BCE event to an event 700 years later seems like a stretch to critics, who see this as Matthew retrofitting Jesus’ story to fit a messianic template.

Defense:

- Matthew’s audience, likely Jewish Christians familiar with the LXX, would have accepted parthenos as a legitimate rendering. The virgin birth could be seen as a typological fulfillment—a pattern from the OT finding greater significance in Jesus.

- “Immanuel” (God with us) is thematically consistent with Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus as divine.

- Ancient Jewish exegesis often applied OT texts flexibly, seeing multiple layers of meaning.

Evaluation: This is one of the most debated examples. Critics have a strong case that Isaiah 7:14 was not originally messianic or about a virgin birth, and Matthew’s application ignores the historical context. However, Matthew’s use reflects a creative hermeneutic common in his era, not necessarily a deliberate fudge but a reinterpretation that assumes divine intent across centuries.

2. Matthew’s Use of Hosea 11:1 – “Out of Egypt I Called My Son”

Claim: Matthew 2:15 cites Hosea 11:1 to link Jesus’ return from Egypt after Herod’s death to the prophecy: “Out of Egypt I called my son.” Criticism:

- Historical Reference: Hosea 11:1 explicitly refers to Israel’s exodus from Egypt under Moses, not a future messianic figure. The “son” is collectively Israel, not an individual.

- Lack of Predictive Element: The verse is a retrospective statement, not a prophecy about a future event. Critics argue Matthew lifts it out of context to create a parallel with Jesus’ life.

- Narrative Convenience: Some suggest Matthew crafted the Egypt sojourn story to mirror the exodus and claim fulfillment, as there’s no independent corroboration of Jesus’ family fleeing to Egypt.

Defense:

- Matthew employs typology, where OT events prefigure NT realities. Israel’s exodus foreshadows Jesus as the true Israel, fulfilling God’s redemptive plan.

- Jewish interpretive traditions allowed such analogical readings, where historical events carried messianic significance.

Evaluation: This is a clear case of Matthew applying a non-prophetic text prophetically. Critics convincingly argue that Hosea 11:1 has no forward-looking intent, making Matthew’s use seem forced. However, within Matthew’s theological framework, the typological connection is intentional, not deceptive, though it stretches modern standards of textual fidelity.

3. Matthew’s Use of Jeremiah 31:15 – Rachel Weeping for Her Children

Claim: Matthew 2:17-18 cites Jeremiah 31:15 to connect Herod’s massacre of Bethlehem’s infants to the prophecy: “A voice was heard in Ramah, weeping and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children.” Criticism:

- Original Context: Jeremiah 31:15 refers to the Babylonian exile, with Rachel (symbolizing Israel’s matriarch) mourning the deportation of her descendants. The verse is followed by hope for restoration (31:16-17), not a prediction of a future massacre.

- Geographical Issue: Ramah (near Jerusalem) is not Bethlehem, creating a locational mismatch. Critics argue Matthew loosely applies the verse to evoke emotional resonance rather than precise fulfillment.

- Historical Doubt: The massacre of the innocents lacks corroboration outside Matthew, leading some to speculate it was a literary device to parallel Pharaoh’s killing of Hebrew infants (Exodus 1-2) and trigger the Jeremiah quote.

Defense:

- Matthew sees Jesus’ life as recapitulating Israel’s history, with the massacre echoing the exile’s suffering.

- “Ramah” and “Bethlehem” could be linked broadly as sites of sorrow in Jewish memory.

- The lack of historical evidence for the massacre doesn’t negate its theological role in Matthew’s narrative.

Evaluation: Matthew’s use of Jeremiah 31:15 is one of the weaker links, as the verse is neither messianic nor predictive. The geographical and contextual disconnects fuel skepticism, and the unhistorical nature of the massacre strengthens the case for a fudge—Matthew shaping the story to fit a scriptural pattern.

4. Matthew’s “He Shall Be Called a Nazarene” (Matthew 2:23)

Claim: Matthew 2:23 states that Jesus living in Nazareth fulfills the prophecy: “He shall be called a Nazarene.” Criticism:

- No Such Prophecy: No OT verse explicitly says the Messiah will be called a Nazarene or come from Nazareth. Critics argue Matthew invented this “prophecy” or misremembered a text.

- Possible Confusion: Some suggest Matthew alludes to Isaiah 11:1, where the Messiah is a “branch” (netzer in Hebrew), loosely tied to “Nazareth.” Alternatively, he might mean Judges 13:5 (Samson as a Nazirite), but Nazirites (consecrated individuals) are unrelated to Nazareth geographically.

- Ad Hoc Reasoning: Nazareth was an obscure village, unlikely to feature in messianic prophecy. Critics see this as Matthew justifying Jesus’ actual hometown post hoc.

Defense:

- Matthew may use a wordplay (netzer/Nazareth) to evoke messianic imagery, a technique acceptable in his cultural context.

- He might refer to a lost or oral tradition not preserved in the OT.

- “Prophets” (plural) suggests a thematic fulfillment rather than a single verse.

Evaluation: This is perhaps the most egregious example, as no clear OT source exists. The netzer theory is speculative, and the Nazirite link is implausible. Matthew’s vague appeal to “prophets” suggests he’s reaching, possibly to address the embarrassment of Jesus hailing from an insignificant town.

5. The Suffering Servant in Isaiah 53 – Applied to Jesus

Claim: Multiple NT writers (e.g., Matthew 8:17, Acts 8:32-35, 1 Peter 2:22-25) apply Isaiah 53’s Suffering Servant to Jesus, portraying him as the one who bears humanity’s sins through his death. Criticism:

- Corporate vs. Individual: In Isaiah’s context, the Servant is often identified as Israel collectively (see Isaiah 41:8, 44:1), suffering for and redeeming the nations. Critics argue NT writers reframe a national allegory as an individual prophecy.

- Selective Use: The NT emphasizes Isaiah 53:4-12 (suffering and atonement) but ignores parts less applicable to Jesus, like the Servant’s prolonged life and offspring (53:10).

- Jewish Interpretation: Pre-Christian Jewish readings rarely saw Isaiah 53 as messianic, viewing the Servant as Israel or a righteous remnant. Critics claim the NT imposes a novel interpretation.

- Historical Fit: Some argue Jesus’ death (public crucifixion) doesn’t match the Servant’s quiet, shame-filled suffering (53:7-9).

Defense:

- Some Second Temple Jewish texts (e.g., 1 Enoch) show messianic individualism emerging, supporting the NT’s reading.

- Isaiah 53’s language (vicarious suffering, death for sins) aligns strikingly with Christian atonement theology, suggesting divine intent.

- Typological fulfillment allows the Servant’s corporate identity to prefigure an individual redeemer.

Evaluation: The NT’s use of Isaiah 53 is compelling in its thematic parallels but problematic in its departure from the probable original intent (Israel as Servant). While not a blatant fudge, the reinterpretation stretches the text’s meaning, especially given the lack of pre-Christian messianic readings.

6. Psalm 22 in the Crucifixion Narratives

Claim: Mark 15:34 and Matthew 27:46 quote Psalm 22:1 (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”) as Jesus’ cry on the cross, implying the psalm’s fulfillment. Criticism:

- Non-Prophetic Psalm: Psalm 22 is a lament by an individual (likely David), not a prediction of the Messiah’s suffering. Critics argue the NT writers cherry-pick verses to match Jesus’ crucifixion.

- Details Don’t Fit: While Psalm 22:16-18 (pierced hands, divided garments) eerily resembles crucifixion, other parts (e.g., 22:4-5, trust in deliverance) don’t align with Jesus’ death.

- Shaping the Narrative: Some scholars suggest the Gospel writers crafted crucifixion details (e.g., casting lots for clothes, John 19:24) to echo Psalm 22, rather than reporting historical events.

Defense:

- Psalm 22’s vivid imagery naturally lent itself to messianic interpretation, especially in light of Jesus’ death.

- Jesus quoting the psalm’s opening could signal its broader relevance, not a verse-by-verse fulfillment.

- Typology again applies: David’s suffering foreshadows the Messiah’s.

Evaluation: The use of Psalm 22 is less a failure than a creative adaptation, but critics have a point that the psalm isn’t prophetic. The suspicion that Gospel details were tailored to fit the psalm strengthens the case for a fudge, though it’s more about theological shaping than outright distortion.

7. Zechariah 9:9 – The Triumphal Entry

Claim: Matthew 21:4-5 and John 12:15 cite Zechariah 9:9 to depict Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on a donkey as fulfilling: “Behold, your king is coming to you, humble, and mounted on a donkey.” Criticism:

- Matthew’s Misquote: Matthew 21:5 uniquely mentions two animals (a donkey and a colt), possibly misreading Zechariah’s poetic parallelism (“a donkey, even a colt”). This leads to the awkward narrative of Jesus riding both (21:7), which critics see as a literalist blunder.

- Contextual Stretch: Zechariah 9:9-10 envisions a victorious king establishing peace, not a figure headed for crucifixion. Jesus’ entry lacks the political triumph implied.

- Historical Question: Some argue the donkey detail was added to fulfill the prophecy, as it’s less prominent in Mark and Luke.

Defense:

- Matthew’s two animals may reflect a Semitic style emphasizing the prophecy’s details, not a mistake.

- Jesus’ humility matches Zechariah’s “lowly” king, redefining messianic triumph spiritually.

- The event’s historicity is plausible, as donkeys were common and symbolic.

Evaluation: Matthew’s handling of Zechariah 9:9 is clumsy, particularly the two-donkey issue, which suggests overzealous literalism. The broader application fits Jesus’ persona but ignores Zechariah’s victorious tone, making this a moderate fudge.

8. Psalm 110:1 – The Lord Said to My Lord

Claim: Jesus (Mark 12:36), Peter (Acts 2:34-35), and Hebrews (1:13) cite Psalm 110:1 (“The Lord said to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand’”) to portray Jesus as the exalted Messiah. Criticism:

- Royal Psalm: Psalm 110 is likely a coronation hymn for a Davidic king, not a messianic prophecy. “My Lord” refers to the king, not a divine figure.

- NT Spin: The NT interprets the second “Lord” as Jesus, implying his divinity, which critics argue exceeds the psalm’s intent.

- Overuse: The psalm’s frequent NT citation (more than any other OT text) suggests it was a convenient prooftext, not a precise prediction.

Defense:

- Some Second Temple Jews saw Psalm 110 as messianic (e.g., Dead Sea Scrolls), supporting the NT’s view.

- Jesus’ resurrection and exaltation align with the psalm’s imagery of divine enthronement.

- The NT’s Christological reading builds on the psalm’s royal theology.

Evaluation: The NT’s use of Psalm 110:1 is less problematic contextually, as messianic readings were plausible in Judaism. However, the leap to Jesus’ divinity pushes the text beyond its likely meaning, though this reflects theological conviction rather than a deliberate fudge.

9. Daniel 7:13-14 – The Son of Man

Claim: Jesus’ self-identification as the “Son of Man” (e.g., Mark 14:62) draws on Daniel 7:13-14, where a “son of man” receives everlasting dominion. Criticism:

- Corporate Figure: In Daniel, the “son of man” likely symbolizes the “saints of the Most High” (7:18, 27), not an individual Messiah.

- Eschatological Shift: Jesus’ use of the title blends Daniel’s cosmic ruler with a suffering figure (Mark 8:31), which critics argue distorts the original vision.

- Ambiguity: The term “son of man” in Aramaic could mean “human” or “I,” suggesting Jesus’ usage wasn’t always prophetic.

Defense:

- Second Temple texts (e.g., 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra) treat the Son of Man as a messianic individual, aligning with Jesus’ self-understanding.

- Jesus’ fusion of suffering and glory reinterprets Daniel creatively, not inaccurately.

- The NT’s eschatological focus matches Daniel’s apocalyptic tone.

Evaluation: The Son of Man issue is complex, but the NT’s individualizing of a possibly corporate figure is a significant reinterpretation. It’s not a clear failure, as messianic readings existed, but it’s a stretch from Daniel’s probable intent.

Broader Observations

- Hermeneutical Context: NT writers used methods like pesher (contemporary application) and typology, common in Second Temple Judaism. What critics call “fudges” were often legitimate interpretive moves in their cultural context, aiming to show Jesus as the climax of Israel’s story.

- Theological Agenda: The NT’s goal was to persuade Jewish and Gentile audiences of Jesus’ messiahship, sometimes prioritizing theological coherence over strict exegesis.

- Critics’ Lens: Modern historical-critical methods emphasize original intent, making NT applications seem forced. Ancient readers, less bound by such standards, likely saw the connections as inspired.

- Historical Reliability: Cases where prophecy shapes narrative (e.g., massacre of the innocents, two donkeys) raise questions about historicity, suggesting some events were crafted to fit OT patterns.

Conclusion

The most egregious examples—Matthew’s “Nazarene” prophecy, Hosea 11:1, and Jeremiah 31:15—stand out for their lack of clear OT grounding or predictive intent. Others, like Isaiah 7:14 and Zechariah 9:9, involve contextual stretches or textual missteps but reflect deliberate theological framing rather than deceit. Isaiah 53 and Psalm 22, while not strictly prophetic, offer striking parallels that the NT capitalizes on. Critics have valid points about exegetical overreach, but the NT writers’ methods were rooted in their era’s interpretive norms, aiming to reveal Jesus as the fulfillment of God’s plan. Whether these are “failures” depends on whether one judges by modern or ancient standards.

Leave a comment