Consider the Following:

Summary: Christianity’s discouragement of doubt contradicts rational inquiry, favoring unwavering belief even in the absence of sufficient evidence. A truly rational belief system would value doubt as an essential, evidence-aligned complement to belief, suggesting that a God who forbids doubt endorses irrationality over truth-seeking.

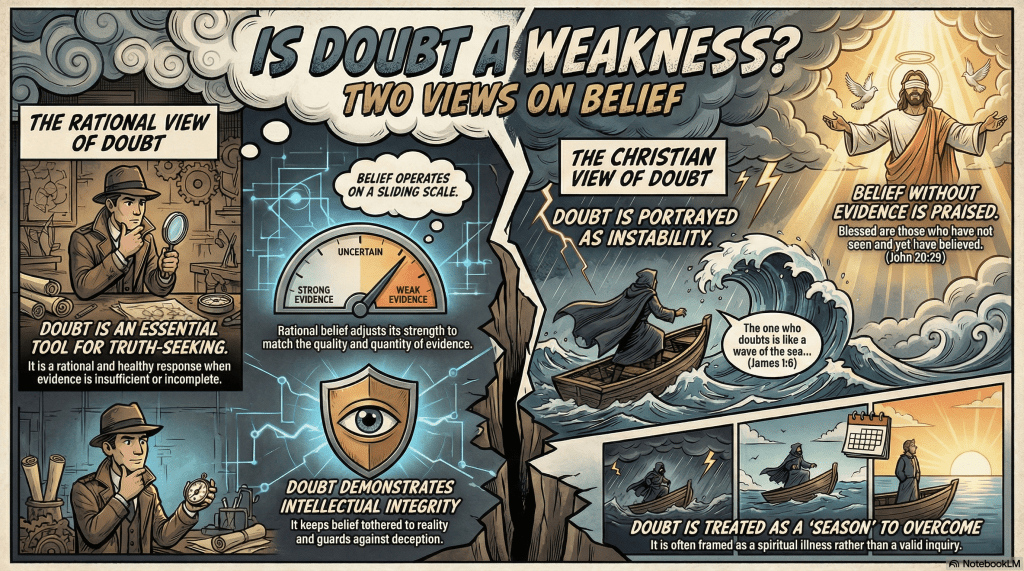

Doubt is essential to the rational mind; it is not a weakness but a rational response to insufficient evidence. Imagine a religion structured in such a way that questioning its claims is discouraged, and faith is presented as virtuous even when divorced from reason. Christianity subtly embeds this discouragement, as seen in verses that characterize doubt as a marker of instability, such as James 1:5-8: “If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you. But when you ask, you must believe and not doubt, because the one who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind. That person should not expect to receive anything from the Lord. Such a person is double-minded and unstable in all they do.” Here, doubt is cast not as a legitimate tool for truth-seeking but as a sign of a fragile mind. Such a system raises fundamental questions about the nature of its deity: Would a rational, all-knowing God truly discourage doubt, the natural response to incomplete evidence?

This notion is bolstered in Matthew 21:21-22. Assuredly, I say to you, if you have faith and do not doubt, you will not only do what was done to the fig tree, but also if you say to this mountain, ‘Be removed and be cast into the sea,’ it will be done. And whatever things you ask in prayer, believing, you will receive. It is clear that doubt is considered a weakness. However, can we legitimately reduce doubt to a weakness in character?

The Epistemic Gradient: Why Doubt Complements Rational Belief

In any epistemically sound framework, doubt and belief coexist along a spectrum aligned with the quality and quantity of evidence. Rationality requires that belief be proportional to evidence—where evidence is partial, so too should belief be tempered by doubt. This epistemic gradient is a basic principle of critical thinking, forming the foundation of all scientific and logical inquiry. A model that insists on full belief where evidence is lacking, or that dismisses doubt as dangerous or unstable, violates this principle and steps outside rational bounds. Thus, any system that scorns doubt when evidence is scarce discourages intellectual honesty, replacing rational inquiry with unfounded certitude.

Jesus and Thomas: An Endorsement of Uninformed Belief?

The story of Doubting Thomas (John 20:29) is illustrative of Christianity’s dubious relationship with doubt. Rather than affirming Thomas’s demand for evidence, Jesus praises those who “believe without seeing,” suggesting that belief without sufficient evidence is more virtuous than belief informed by investigation. This preference for blind belief over rational inquiry underscores a foundational tension: Is this an endorsement of irrationality? Would a God committed to truth and rationality discourage the very doubt that guards against deception? Such a stance seems to contradict the values of a deity presumed to embody truth.

Faith and Rationality: A Biblical Incongruity

The Bible’s insistence on faith as a virtue is especially clear in 2 Corinthians 5:7: “We live by faith, not by sight.” This emphasis on faith over empirical evidence encourages adherents to believe without reason and to resist the self-critical approach that is essential to rational belief. Here, faith is elevated as a goal in itself, encouraging a form of belief that is immune to the scrutiny of evidence. This stance aligns belief with certainty rather than with justification, contradicting the principles of rational belief, which always seeks alignment with the available evidence.

Rational Belief as Evidence-Based Belief

At the heart of a rational approach to belief is the epistemic principle that belief should proportionally correspond to the quality and weight of evidence. Thus, rational belief is not simply certainty but justified belief that aligns with reality. An insistence on unwavering belief where evidence is absent not only defies reason but entrenches ignorance. By discouraging doubt, Christianity effectively shields itself from critical scrutiny, functioning as a closed system that resists rational challenge.

Conclusion: A God Who Prohibits Doubt Undermines Rationality

A worldview that devalues doubt promotes irrationality. When a doctrine treats doubt as a defect rather than a rational counterpart to belief, it positions itself outside of a rational epistemic framework. This dismissal of doubt serves to protect the system from examination, implying a fear of scrutiny inconsistent with any claim to truth. If belief is to be rational, it must align with evidence; when doubt is dismissed, belief exceeds the evidence, becoming mere dogma. A deity who prohibits doubt, then, undermines the rationality necessary for genuine truth-seeking.

Logical Analysis:

P1: Rational belief adjusts to the degree of relevant evidence; doubt complements belief where evidence is lacking.

P2: Christianity discourages doubt, endorsing belief that often exceeds evidence.

Conclusion: Christianity, by discouraging doubt, promotes an irrational framework for belief.

Would an all-knowing, rational God design a system that discourages inquiry and values unexamined faith over evidence-based belief?

A Season of Doubt?

In Christian circles, doubt is often framed as an unfortunate “season” or a temporary crisis to be endured and then overcome. Christian leaders frequently present doubt as a phase in the believer’s journey, a period of testing or spiritual struggle to be left behind as faith matures. This perspective suggests that doubt is something to be tolerated rather than integrated, an emotional obstacle rather than a cognitive response to evidence. By casting doubt as a transient weakness, leaders reinforce the notion that a return to unwavering faith is the only acceptable outcome, sidelining any suggestion that doubt might be a rational counterpart to belief.

From a rational perspective, however, doubt serves as an essential mechanism, allowing belief to align more closely with the degree of evidence available. Rational belief operates on a gradient where strong evidence supports strong belief, while weaker evidence naturally produces a proportionate level of doubt. This model sees doubt not as a deviation but as a rational, evidence-based response, adjusting belief to match reality. By instead portraying doubt as a “season,” Christian leaders implicitly discourage this alignment with evidence, promoting an emotional commitment to belief regardless of what the evidence might suggest.

The framing of doubt as a phase to be overcome, then, subtly reinforces a belief system resistant to critical examination. Leaders encourage believers to interpret doubt as a momentary lapse or an attack on their faith, rather than as a natural element of rational inquiry. In doing so, they not only discourage honest questioning but also foster an environment where doubt is viewed as an inherent weakness rather than a sign of intellectual integrity. This approach perpetuates a rigid framework, where faith becomes disconnected from the principles of evidence-based belief, reducing doubt to a mere obstacle on the path to certainty.

A Companion Technical Paper:

See also:

The Logical Form

1. Doubt as a Rational Response to Evidence

- Premise 1: Rational belief aligns with the degree of evidence; when evidence is partial or weak, a proportional level of doubt is rational.

- Premise 2: Christianity discourages doubt, often framing it as a sign of instability or weakness rather than as a rational response to insufficient evidence.

- Conclusion: Christianity promotes an irrational stance on belief by discouraging doubt and encouraging faith that exceeds the available evidence.

2. Doubt and Belief as Complements

- Premise 1: In a rational framework, doubt and belief function as complements along a gradient, where belief increases with evidence and doubt arises in the absence of conclusive evidence.

- Premise 2: Christian leaders frame doubt as a “season” or temporary crisis, suggesting it should be overcome rather than seen as a rational complement to belief.

- Conclusion: By framing doubt as an undesirable phase, Christianity promotes a rigid belief structure that does not adapt to the evidence and discourages rational inquiry.

3. Doubt as Intellectual Integrity

- Premise 1: Intellectual integrity requires an openness to doubt as it enables belief to adjust in accordance with evidence, ensuring beliefs remain evidence-aligned.

- Premise 2: Christian teachings often characterize doubt as a defect or weakness, implying that it should be resolved in favor of unwavering faith.

- Conclusion: Christianity’s view of doubt as a weakness undermines intellectual integrity, replacing an evidence-aligned belief with a model of unexamined faith.

4. Doubt as the Antithesis of Evidence-Misaligned Faith

- Premise 1: Intellectual integrity requires an openness to doubt as it enables belief to adjust in accordance with evidence, ensuring beliefs remain evidence-aligned.

- Premise 2: Christian teachings often characterize doubt as a defect or weakness, implying that it should be resolved in favor of unwavering faith.

- Conclusion: Christianity’s view of doubt as a weakness undermines intellectual integrity, replacing an evidence-aligned belief with a model of unexamined faith.

5. The Epistemic Gradient in Rational Belief

- Premise 1: Rational belief follows an epistemic gradient, where belief corresponds to the level of evidence, and doubt naturally arises with inconclusive evidence.

- Premise 2: Christian doctrine often dismisses doubt as undesirable, labeling it a weakness that undermines faith, rather than recognizing it as part of a rational belief framework.

- Conclusion: By discouraging doubt, Christianity promotes a belief system that resists the epistemic gradient, favoring unexamined faith over a balanced, evidence-responsive approach.

6. An Irrational Model of Divine Expectation

- Premise 1: If a deity values truth-seeking, it would encourage belief proportionate to evidence and support the presence of doubt where evidence is lacking.

- Premise 2: Christianity teaches that doubt is a weakness or failing and that unwavering faith is a virtue, even when evidence is insufficient.

- Conclusion: A God who discourages doubt and demands unwavering belief endorses irrationality over a rational, evidence-based approach to truth.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Role of Doubt in Rational Belief

CHRIS: I’ve always understood doubt as a temporary phase—a season that believers go through but are meant to overcome. Faith requires stability and certainty, and doubt just seems to undermine that. Isn’t it better to focus on strengthening belief rather than letting doubt linger?

CLARUS: I see where you’re coming from, Chris, but I think viewing doubt as a weakness misses something crucial. In a rational framework, doubt is actually a necessary part of belief. Rational belief doesn’t demand absolute certainty; instead, it aligns itself with the degree of evidence. Where the evidence is lacking, doubt naturally arises, serving as a rational complement to belief.

CHRIS: But isn’t faith more about trust, even when evidence is limited? Jesus even commended those who “believe without seeing.” Isn’t that the kind of strength we’re called to in Christianity?

CLARUS: That’s exactly where the problem lies. When belief disregards the relevant evidence and insists on certainty without a corresponding basis, it steps outside of rational inquiry. For belief to be rational, it must map to the strength of the evidence. Encouraging blind faith—as in believing without sufficient evidence—actually discourages intellectual integrity because it promotes certainty without grounding.

CHRIS: I understand that doubt can be part of growth, but if it leads to losing faith altogether, doesn’t that show instability? I mean, scripture talks about doubt as something harmful. James, for instance, says, “The one who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind.” It sounds like doubt makes a person unstable.

CLARUS: From a rational perspective, doubt doesn’t signify instability; it signifies evidence-based belief. When the evidence is weak or ambiguous, doubt becomes an expression of intellectual honesty, an adjustment that aligns belief with reality. To dismiss doubt as weakness is to ignore how rational belief works—belief should correlate with the epistemic gradient, adjusting to the evidence.

CHRIS: But if we keep doubting, isn’t that just weakening our faith? Doesn’t it lead to endless questioning?

CLARUS: Not if it’s balanced. Doubt isn’t about endlessly questioning; it’s about calibrating belief to the evidence. Dismissing doubt as merely a “season” ignores this balance, encouraging an approach that’s resistant to scrutiny. Rational belief requires doubt when evidence is lacking; that’s what makes it responsible. Treating doubt as something to be “overcome” creates a framework where belief becomes rigid and detached from critical evaluation.

CHRIS: So you think faith shouldn’t require this level of certainty? I was taught that faith is the strength to believe even when we can’t see.

CLARUS: The issue is that faith often gets framed as a virtue that discourages the self-critical inquiry essential to rational belief. By elevating belief without evidence, the Christian view can isolate itself from rational scrutiny. If a deity truly values truth-seeking, then doubt shouldn’t be seen as a flaw but as a rational response to incomplete information. Wouldn’t an all-knowing God encourage belief proportionate to evidence?

CHRIS: I hadn’t thought about it that way. But if doubt is a rational part of belief, are you saying faith itself is irrational?

CLARUS: Not necessarily. Faith can have value, but when it discourages doubt and detaches itself from evidence-based belief, it veers into irrationality. True rational belief embraces doubt as a natural counterpart. In contrast, a belief system that frames doubt as a threat, rather than an ally in the search for truth, may inadvertently promote ignorance over understanding.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

1. The Scale of Justice

Imagine a scale weighing evidence in a courtroom. If the evidence is heavy on one side, the scale tips accordingly; if evidence is sparse, the scale shows balance or uncertainty. In a rational belief system, belief is like this scale—it should reflect the degree of evidence. Doubt is simply the scale’s reaction when evidence doesn’t decisively tip one way or the other. If the scale were forced to always lean in one direction, regardless of evidence, it would be misleading, just as belief is when doubt is discouraged.

2. The Scientist’s Hypothesis

A scientist doesn’t hold to a hypothesis without scrutiny or continual testing. They modify their level of confidence based on new data, holding a flexible stance that accommodates doubt when results are inconclusive. In this way, doubt functions as a rational counterbalance to premature certainty, pushing for evidence-based conclusions. For belief to remain rational, it must act like the scientist, adjusting with doubt where evidence is weak or ambiguous. Discouraging doubt is like a scientist rejecting any findings that don’t confirm their hypothesis, which would undermine the credibility of their work.

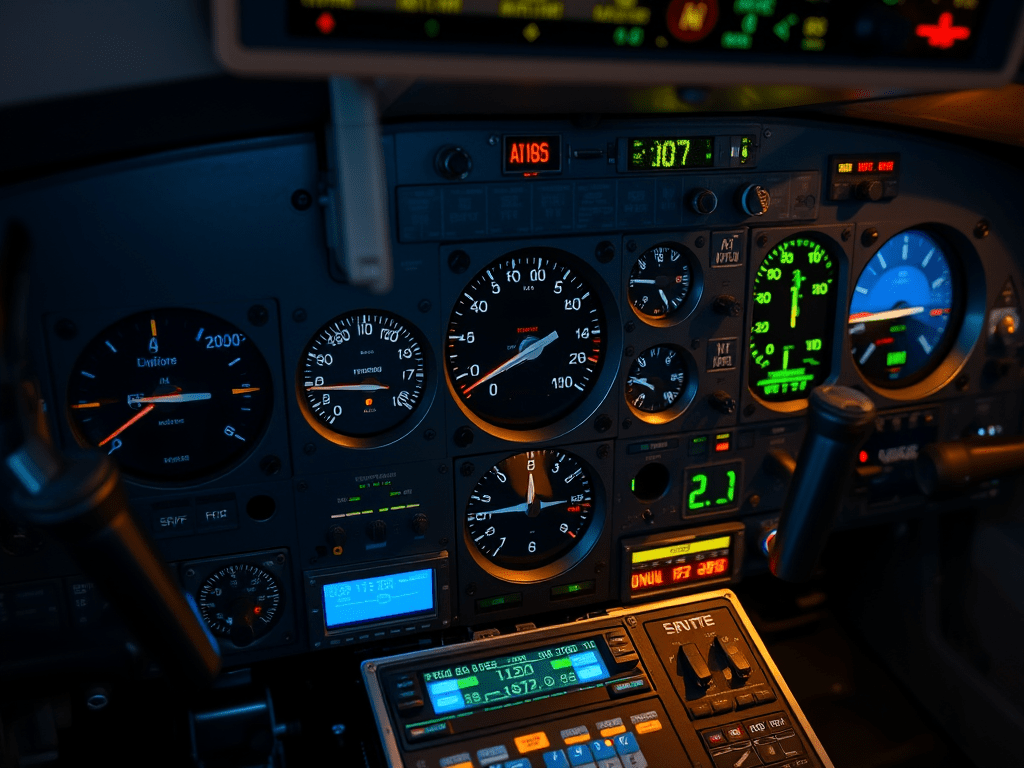

3. The Pilot’s Compass

A pilot relies on a compass to navigate, adjusting course based on small corrections as they travel. If they ignored these corrections, insisting they’re on course regardless, they could end up far from their destination. Doubt in belief acts like these course corrections—an essential alignment with reality based on current information. Insisting on an unchanging belief without room for doubt is like ignoring the compass, ultimately leading one further from a grounded, evidence-based belief system. Just as a pilot’s success relies on flexibility, so does rational belief on the presence of doubt.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Faith as Trust Beyond Reason

Theologians might argue that faith inherently involves an element of trust that goes beyond empirical evidence. They could assert that belief in God is not irrational simply because it does not align with a purely evidence-based model. Faith, they might say, transcends human reasoning, calling believers to trust in God’s character and promises, even when evidence is unclear or limited.

2. Doubt as a Temporary Test, Not a Permanent State

Many Christian thinkers view doubt as a necessary but temporary “season” intended to strengthen faith rather than as an ongoing counterpart to belief. They might argue that doubt can serve as a spiritual trial, meant to challenge and refine belief, but that ultimate resolution and trust in God are expected. This perspective would frame doubt as a phase believers are called to overcome, viewing faith as a commitment that should ultimately outlast temporary uncertainty.

3. Faith Grounded in Relationship, Not Just Evidence

Theologians may argue that faith is grounded in a relationship with God, not simply in an intellectual assessment of evidence. Just as trust in personal relationships often goes beyond rational calculations, faith in God is based on trust in His nature and promises. From this perspective, doubt is seen as an understandable human reaction but is overcome by personal experience and the relational trust developed over time with God.

4. A Distinct Epistemology for Faith

Theologians might contend that faith operates within a different epistemological framework, where spiritual truths are known by revelation rather than by empirical evidence alone. In this view, faith is a legitimate, separate way of knowing that can provide certainty in matters beyond human comprehension, where doubt would be inappropriate. For them, faith and reason complement each other, but faith occupies a unique domain that addresses the ultimate questions science and rationality cannot answer.

5. Doubt as a Consequence of Human Limitation

Another theological perspective might argue that doubt arises from human limitations and an incomplete understanding of divine truths, rather than from a rational need for evidence. Theologians could claim that doubt is a result of human finitude and that complete understanding of God is beyond human capability. Thus, faith involves humility and acceptance of divine mysteries, with doubt seen as a natural struggle but ultimately overcome by surrender to divine wisdom.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “Faith as Trust Beyond Reason”

While faith can involve trust, framing it as trust “beyond reason” undermines rational belief by dismissing the need for evidence. Trust in any context is most sound when it aligns with reliable information; therefore, trust without evidence risks approximating blind faith, where belief persists regardless of rational support. A belief system that expects trust without rational basis does not merely transcend evidence—it detaches from a standard of credibility, making it indistinguishable from superstition. If trust in God demands reason-defying belief, then such a faith forfeits the claim to rationality.

2. Response to “Doubt as a Temporary Test, Not a Permanent State”

Framing doubt as a transient phase to be overcome presumes that certainty is always attainable, which is not consistent with the rational pursuit of truth. Doubt is not merely a “spiritual trial” but an integral part of evidence-based belief, indicating the mind’s alignment with the actual quality of evidence. Insisting that faith should ultimately replace doubt implies a commitment to unquestioned belief regardless of the evidence, which fosters rigidity rather than intellectual growth. To view doubt as a failing to be conquered is to dismiss the essential role it plays in keeping beliefs evidence-aligned.

3. Response to “Faith Grounded in Relationship, Not Just Evidence”

While relationships can involve trust beyond strict rationality, trust in God is not analogous to trust in a human partner, as it requires belief in unobservable claims about the divine. A relationship with a deity is fundamentally different from interpersonal trust, as there is no shared reality or empirical basis for interaction with God. Thus, relying solely on a “relationship” with an unseen entity lacks the evidence that justifies trust in human relationships. Faith that discounts evidence in favor of relational trust with an invisible, unverifiable being leans toward wishful thinking, not rational belief.

4. Response to “A Distinct Epistemology for Faith”

The claim that faith operates within its own epistemology ignores the fundamental need for consistency in determining truth. By isolating faith from empirical evidence and rational standards, this response implies a double standard where religious claims are exempt from critical scrutiny. If faith is beyond rational inquiry, then its truth claims become unfalsifiable and indistinguishable from any other irrational belief. A valid epistemology should allow beliefs to be tested against reality, and a system that cannot be scrutinized for coherence risks validating belief without basis.

5. Response to “Doubt as a Consequence of Human Limitation”

Presenting doubt as a result of human limitation may appear humble, but it fails to address the need for justified belief based on evidence. While humans are indeed finite, this does not mean they should abandon the standard of evidence to uphold beliefs that lack support. Encouraging faith in mysteries as a solution to doubt invites intellectual surrender rather than promoting rational inquiry. If divine mysteries are invoked as beyond comprehension, they become immune to disproof, effectively making them unaccountable to rational assessment, which weakens the claim of faith as a reasonable belief.

Clarifications

Religious Tactics to Limit Doubt

Religious communities often portray doubt not as a normal and rational process but as a failure or even a spiritual “disease” that endangers a believer’s faith. Leaders typically frame doubt as an attack on the believer’s stability, a symptom of weak or misguided faith that could lead to spiritual or communal estrangement. To counteract this, religious leaders employ tactics aimed at containing doubt, limiting the doubter’s exposure to non-theistic or critical perspectives, and rallying the community to “pray for” the individual. This approach effectively isolates the doubter within a controlled framework, reinforcing the belief system while subtly emphasizing the threat of alienation if they drift too far from accepted doctrines.

A common strategy is to restrict access to any challenges that might deepen doubt, often by discouraging engagement with secular or critical sources. Instead, religious leaders may flood the doubter with theistic arguments, apologetics, or curated stories of doubt overcome by renewed faith. This tactic insulates the believer, creating an echo chamber that continually reaffirms doctrinal certainty and downplays the validity of skepticism. The emphasis is often on “strengthening faith,” which is implicitly defined as eliminating doubt rather than examining it critically. This pressure to reject contrary perspectives frames doubt as a deviation from the community’s shared belief, making it a sign of personal failing rather than a rational process.

Another tactic involves the mobilization of the congregation to “pray for” the doubter, framing doubt as a temporary weakness to be corrected. The act of communal prayer is often presented as an act of support, but it also places subtle social pressure on the doubter, conveying the expectation that they will eventually “return” to unshakable faith. This collective response reinforces the idea that doubt is a temporary crisis, something the community must work together to resolve rather than a legitimate inquiry. It sends a strong, implicit message: doubt is undesirable, and a strong, unquestioning faith is the ideal. By organizing the community to collectively respond, religious leaders instill a sense of communal obligation, pushing the doubter toward conformity under the weight of group expectations.

Finally, many religious leaders subtly underscore the threat of alienation if the doubter’s journey leads them too far from the faith. They often suggest that doubt, if allowed to flourish unchecked, could result in a “major course correction” that might sever the individual’s bond with their faith community. This suggestion of potential alienation serves as a powerful tool, subtly coercing the doubter to either abandon their questioning or face social estrangement. In tightly knit religious communities, this threat of exclusion can be profound, as many members rely on their community for social, emotional, and sometimes financial support. The doubter is thus pressured to abandon rational inquiry to maintain belonging, reinforcing the belief that faith without doubt is both safer and more socially acceptable.

Through these tactics, religious leaders shape doubt into a failure or disease rather than a natural part of intellectual growth. By framing doubt as a failing to be cured, restricting critical perspectives, and emphasizing the threat of alienation, they protect the community’s shared belief system from the challenge of rational inquiry. In doing so, they promote an environment where faith without question is valorized, while genuine curiosity and critical engagement are seen as risks to be managed and minimized.

Dialogue: A Hypothetical Rational Jesus

Jesus and Thomas Stand Inside a Quiet Upper Room, the Other Disciples Looking On

Thomas (with a cautious but sincere tone):

Master, I have heard the others say you have risen, and I trust them as my friends. Yet, as you know, I have doubted because I have not seen the wounds with my own eyes. I am not certain what to believe. The idea of your resurrection is so extraordinary that I struggle to accept it fully without something more tangible. May I, Lord, see and perhaps touch your wounds, so my heart can rest on firmer ground?

Jesus (with understanding and warmth):

Thomas, I appreciate your honesty and your careful approach to belief. Some might think faith requires no evidence, but you have shown the willingness to ensure that your conviction maps properly to the evidence you have at hand. It is wise, not shameful, to desire more information when the claim is great. After all, no one’s trust should rest solely on hearsay if it can be strengthened by direct engagement.

Thomas (looking relieved):

Then you do not condemn me for my hesitation? You do not see my request as weakness?

Jesus (smiling reassuringly):

Not at all, Thomas. If rational belief is a degree of belief that aligns with the relevant evidence, then by seeking more evidence you are showing respect for truth. Rather than accepting an extraordinary claim blindly, you wish to scale your belief proportionally to the support it receives. That is not weakness; that is the mark of someone who cares deeply that what he believes is indeed true.

Thomas (quiet awe):

I am grateful, my Lord, that you understand. May I then see your wounds, so my confidence can rise from uncertainty to a firmer conviction?

Jesus (extending his hands and showing his side):

Of course. Behold, the marks of the nails in my hands and the place in my side that bears witness to my suffering. Examine them as you need. You have already seen much—my life, my works, and my teachings. Now this, too, shall add to the body of evidence on which you base your faith.

Thomas (leaning forward and gently touching the scars, his voice steady and moved):

Yes, Lord, I see now. My doubt diminishes as my trust grows proportionally to this new confirmation. Where before I hovered in uncertainty, I now stand on firmer ground. You truly have conquered death, and I believe in you more fully than before.

Jesus (placing a hand on Thomas’s shoulder):

Thomas, your approach honors truth. You did not accept claims lightly, nor did you close yourself off from the possibility that they might be genuine. By striving to ensure your belief maps to the evidence available to you, you have chosen the path of a careful and thoughtful seeker. This is commendable, not condemnable.

Thomas (tears of relief welling in his eyes):

My Lord and my God, my belief now is stronger, its strength proportionate to the fullness of the reality before me. I thank you for understanding my need for coherence and clarity, and for guiding me toward a more grounded faith.

Jesus (with kind affirmation):

Blessed are you, Thomas, for you now believe with a more robust conviction that has grown naturally from the evidence you have encountered. May all who follow learn from your example—that faith need not be divorced from reason, and trust can be strengthened, not weakened, by a rational pursuit of truth.

Jesus (turning to the other disciples, his voice gentle but firm):

And now, to all of you who watch, know this: There will be many who believe easily without much evidence, and their hearts may still be sincere. Yet, I tell you, blessed are those who earnestly seek further confirmation when they confront extraordinary claims. For as Thomas’s faith is now more deeply grounded, so too shall the conviction of those who continually refine their trust according to what is real and true. Let no one fear the honest pursuit of understanding. It is a path that ensures belief remains in harmony with reality, ever aligned with the evidence that supports it.

Note:

It is important to clarify that a rational pursuit of truth does not guarantee an ever-increasing belief, even in religious or spiritual claims. While the dialogue above presents a scenario in which Thomas’s belief is strengthened by evidence, rational inquiry can also lead to the opposite outcome if the newly uncovered information or careful scrutiny fails to support the claim at hand. By its nature, reasoning according to evidence entails that trust—and hence belief—must remain open to revision in light of new data.

If the evidence were disconfirming, meaning it contradicted or failed to substantiate the core assertion (e.g., had Thomas discovered no wounds or caught Jesus in a deception), then his degree of belief should logically decrease. This reduction in confidence is not a flaw in the rational process but rather its defining characteristic: rational inquiry adjusts belief proportions in response to the quality and quantity of evidence. In other words, applying reason impartially means acknowledging that one’s confidence may well diminish if the facts do not align with the initial expectation.

This epistemic flexibility ensures that belief—whether religious, scientific, or philosophical—is not locked into a fixed position unjustified by the world’s realities. Instead, it remains adaptable, ready to shift as stronger evidence emerges. Therefore, while the story of Thomas’s encounter shows how skepticism can be resolved by confirming evidence, it also implies that skepticism could (and should) increase if the pursuit of evidence reveals disconfirming factors.

Leave a comment