Consider the Following:

Summary: This post examines the justice of penal substitution, highlighting its inconsistency with principles of rehabilitation, retribution, and fairness while questioning its alignment with biblical and human legal standards. It challenges the notion that an innocent person, such as Jesus or a victim’s mother, should bear the punishment for another’s wrongdoing, exposing contradictions within biblical texts and the logical implications of such practices.

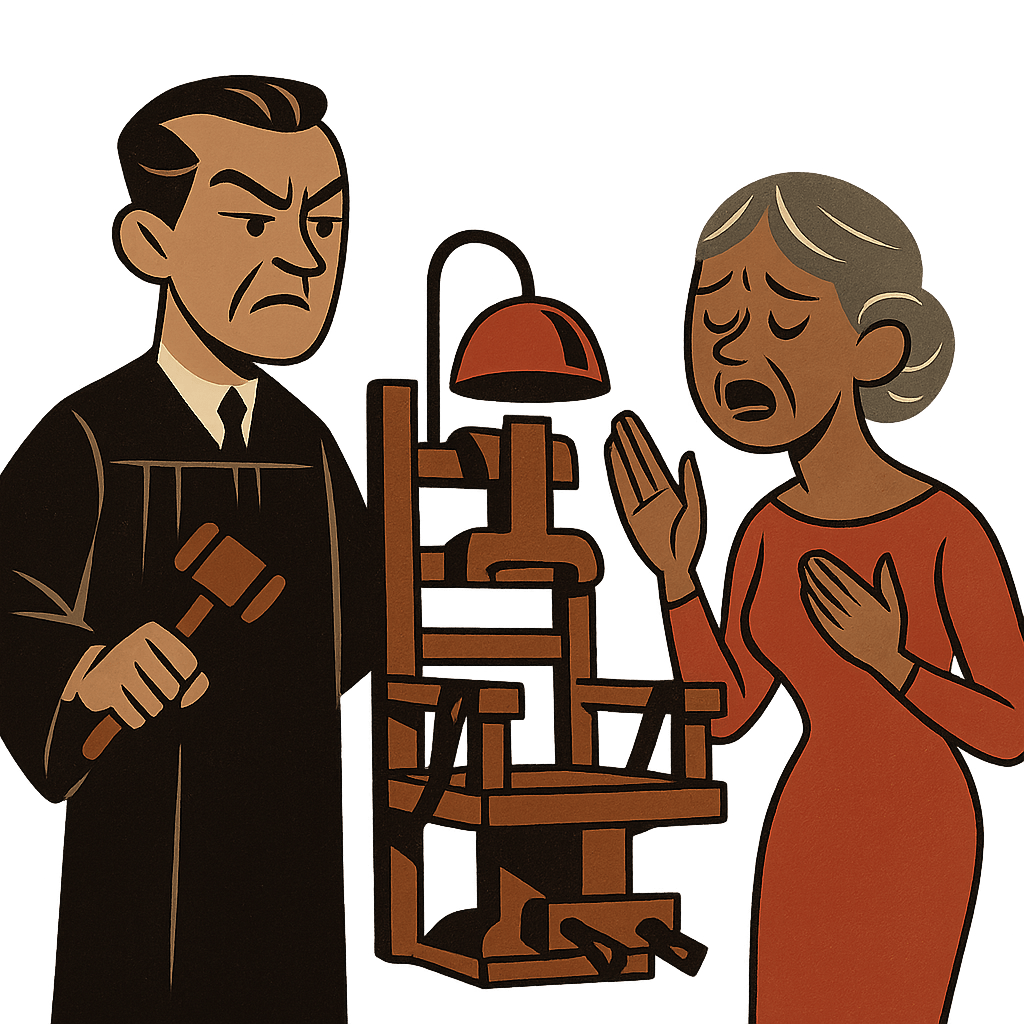

Imagine Henry, who has confessed to multiple murders, stands before a judge. His mother pleads for his release, offering to take his place in the electric chair. What would a just judge decide? Would it matter if Henry accepted his mother’s offer and vowed to reform? Wouldn’t this merely result in another innocent victim? If a single lie truly warrants eternal damnation, could it ever be just to eternally condemn someone who has never lied as a substitute for the actual liar?

Similarly, is it just to have an allegedly innocent Jesus tortured in place of those who committed the offenses?

Some legal systems have permitted the sentences of criminals to be served by innocent friends or family members. Is this just? Let’s examine Henry’s scenario within the framework of common justifications for the death penalty.

Rehabilitation

Could Henry’s mother’s substitutionary death in the electric chair motivate Henry to change his ways? Is it reasonable to suggest that the best method of rehabilitating criminals is to execute their mothers while releasing the actual criminals back into society?

Retribution

The idea that Henry should die because his victims died is intuitive. But what fundamental principle of justice would justify killing his innocent mother in a manner similar to how her son killed his victims? Allowing compassionate individuals to volunteer to die or suffer for those who lack compassion and harm is absurd and would invert our notion of justice.

Appeasement of Wrath

Suppose any human who doesn’t acknowledge the Christian God angers Him to the extent that any love He might have had vanishes, compelling Him to eternally damn that person to hell. Would eternally damning the offender’s mother appease God’s wrath? If someone mutilated your face with a knife, would your anger dissipate if that person’s mother were sentenced to 30 years in prison for her child’s offense? Wouldn’t that dissipation be accompanied by the realization that a horrific legal injustice has been committed against the mother? If justice were based on the judge’s degree of anger, and the judge believed that any term of damnation less than eternal would not appease him, what could we say about the emotional stability of that judge?

Some Christian leaders conflate examples in civil law, where family members may be held financially liable for debts incurred by others, with examples of penal substitution in criminal law. Does a judge permitting a mother to pay her son’s civil settlement equate to allowing her to serve her son’s 30-year sentence for aggravated assault?

Christian leaders also attempt to justify the intuitively unjust notion of penal substitution found in the Bible by invoking laws made by fallible humans. Can potentially flawed laws created by flawed humans support the justice of divine laws? One such law is vicarious liability, where someone is held financially liable for the damaging actions of others, such as a company being held liable for its employees’ mistakes. Few, if any, such laws require someone to be imprisoned for another’s criminal actions. Most would recognize such a law as unjust. Invoking an unjust human law to defend a biblical notion of justice undermines the idea that divine laws supersede human laws.

Even the Bible affirms in one passage that only the one who commits the sin can be punished for that sin:

“The soul who sins is the one who will die. The son will not share the guilt of the father, nor will the father share the guilt of the son.” (Ezekiel 18:20)

Yet, in another book of the Bible, it appears that children ought to suffer punishment for the sins of their fathers:

“You shall not bow down to [idols] or worship them; for I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me.” (Exodus 20:5)

This contradiction raises questions about the consistency of the biblical stance on justice and punishment.

The Contradiction of Penal Substitution

Despite the fervent defense of penal substitution within Christian theology, it is a practice that Christians would undoubtedly condemn in a real-world legal context. Consider the case of Henry’s mother, who volunteers to take her son’s place in the electric chair. No Christian would argue that such an act is just or that it satisfies the demands of justice in any coherent way. Instead, they would likely recognize that punishing the innocent mother while freeing the guilty son undermines the very foundations of justice. This reveals a critical inconsistency: what is rejected as unjust in a courtroom is somehow embraced as divinely righteous in theology.

Conceptual Foundations and the Role of Personal Accountability

A just society depends on personal accountability. Punishing the innocent in place of the guilty erodes trust in the legal system and perpetuates cycles of harm, as it fails to rehabilitate offenders or deter future crimes. If justice is to have any meaningful foundation, it must hold individuals accountable for their own actions rather than allowing others to suffer for their wrongdoings. Christians would agree with this principle in any secular context, acknowledging that a system permitting penal substitution would be chaotic and unjust.

The Injustice of Substitution in Theology

Yet, when it comes to their theology, Christians often set aside these social intuitions. The notion that Jesus, allegedly sinless, bore the punishment for humanity’s sins is central to Christian belief, but it fails the same scrutiny. If it is unjust to sentence a criminal’s mother to death for her son’s crimes, how can it be just to sentence Jesus to death for humanity’s sins? The inconsistency is striking and raises deeper questions about whether the concept of divine justice, as framed in Christian doctrine, aligns with any coherent behavioral framework.

Conclusion

If Christians would rightly condemn the substitution of a criminal’s mother for the criminal’s incarceration or death, they must also confront the inconsistency of defending penal substitution in their theology. Justice, whether divine or human, cannot be just if it punishes the innocent and exonerates the guilty. To accept this contradiction is to undermine the very principles of fairness and accountability, that underpin any credible notion of justice. Recognizing this inconsistency invites Christians to reexamine the foundations of their beliefs and seek a more coherent and compassionate understanding of justice.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: The Contradiction of Penal Substitution

- Premise 1: Christians would condemn the punishment of an innocent mother in place of her guilty son in a real-world legal context.

- Premise 2: Penal substitution, as presented in Christian theology, involves punishing the innocent (Jesus) in place of the guilty (humanity).

- Conclusion: Therefore, there is a contradiction in accepting penal substitution in theology while rejecting it as unjust in real-world legal contexts.

Argument 2: Justice Requires Personal Accountability

- Premise 1: A just society depends on individuals being held accountable for their own actions.

- Premise 2: Punishing the innocent for the actions of the guilty erodes trust in the legal system and fails to rehabilitate offenders or deter future crimes.

- Conclusion: Therefore, justice cannot involve punishing the innocent on behalf of the guilty, as this undermines the principles of accountability and fairness.

Argument 3: Penal Substitution Fails to be Just

- Premise 1: It is unjust to sentence a criminal’s mother to death for her son’s crimes because she did not commit the offense.

- Premise 2: Similarly, it is unjust to sentence Jesus, allegedly sinless, to death for humanity’s sins because he did not commit the offenses.

- Conclusion: Therefore, penal substitution fails to meet standards of justice both in real-world and theological contexts.

Argument 4: Injustice of Divine Justice in Penal Substitution

- Premise 1: Punishing the innocent and exonerating the guilty undermines the principles of justice.

- Premise 2:Divine justice, as presented in Christian theology, relies on the idea of penal substitution, which involves this exact practice.

- Conclusion: Therefore, divine justice as framed in Christian theology is inconsistent with any coherent framework of justice.

Argument 5: Logical Inconsistency in Christian Beliefs

- Premise 1: Christians would rightly condemn the substitution of a criminal’s mother for the criminal’s punishment as unjust.

- Premise 2: Defending penal substitution in theology involves endorsing the substitution of an innocent party (Jesus) for the guilty (humanity).

- Conclusion: Therefore, Christians must confront the logical inconsistency of rejecting penal substitution in a secular context while defending it in theology.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Justice of Penal Substitution

CHRIS: The idea of penal substitution is central to Christianity. Jesus, being sinless, took on the punishment for humanity’s sins, offering a path to forgiveness and reconciliation with God.

CLARUS: But doesn’t penal substitution undermine the principles of justice? If someone commits a crime, it’s unjust to punish an innocent person in their place, regardless of their willingness to bear the punishment.

CHRIS: It might seem that way, but Jesus’s sacrifice is unique because it satisfies both justice and mercy. God’s wrath is appeased, and humanity can be saved.

CLARUS: Let’s test that idea. Imagine a courtroom where a murderer’s mother volunteers to take his place in the electric chair. Would you call that act just?

CHRIS: Of course not. It would be wrong to punish an innocent person for someone else’s crime.

CLARUS: Exactly. You wouldn’t defend penal substitution in a legal context, yet you defend it in your theology. Isn’t that a contradiction? You’re rejecting a principle of justice in one domain while embracing it in another.

CHRIS: But Jesus’s case is different. He willingly took on the punishment, knowing it was the only way to save humanity.

CLARUS: Willingness doesn’t make the act just. If Henry’s mother willingly chose to die for her son, the judge would still be wrong to allow it. The essence of justice is holding the guilty accountable, not punishing the innocent. Wouldn’t you agree?

CHRIS: I see your point, but God’s justice operates on a higher plane, and His ways are beyond our understanding.

CLARUS: That sounds like an appeal to mystery, which doesn’t solve the underlying problem. If divine justice demands punishing the innocent, then it conflicts with the very principles of justice that you and I value. How can a just God behave in a way that you’d condemn in human courts?

CHRIS: But without Jesus’s sacrifice, humanity would be condemned. His death was an act of love to save us from eternal separation from God.

CLARUS: Let’s revisit the electric chair analogy. Suppose the judge allowed Henry’s mother to die, hoping it would rehabilitate Henry or deter future crimes. Wouldn’t that outcome still be tainted by the injustice of punishing the wrong person?

CHRIS: Yes, I suppose it would.

CLARUS: Then how does punishing Jesus, someone who didn’t commit any sins, address humanity’s crimes? If justice is violated in the process, the entire foundation of this atonement collapses.

CHRIS: You’re suggesting that penal substitution cannot reconcile justice and mercy, correct?

CLARUS: Precisely. If justice requires holding people accountable for their actions, then penal substitution is inherently unjust. Christians would rightly condemn this in secular courts, so why should they accept it in theology?

CHRIS: I’ll admit, this raises questions I hadn’t fully considered. If you’re right, it might be worth reevaluating how penal substitution aligns with the principles of justice we claim to uphold.

CLARUS: That’s all I ask. Justice, whether human or divine, must operate on a coherent foundation. Anything less undermines its credibility.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Substitute Driver

Imagine a reckless driver who causes a deadly car accident due to their negligence. When brought to court, the driver’s friend, who is known to be a law-abiding citizen, offers to serve the prison sentence in their place.

- Key Question: Would this substitution be considered just, even if the friend willingly volunteers?

- Analysis: Punishing the innocent friend fails to hold the reckless driver accountable and sends a message that justice can be bypassed through substitution, undermining trust in the legal system.

Analogy 2: The Dishonest Employee

Consider a situation where an employee embezzles money from a company, and the manager, out of loyalty to their subordinate, offers to repay the stolen funds and serve the resulting prison sentence.

- Key Question: Does the manager’s willingness absolve the employee of their crime?

- Analysis: While the repayment might restore the financial loss, imprisoning the innocent manager leaves the guilty employee unaccountable, perpetuating injustice and failing to deter future misconduct.

Analogy 3: The Classroom Cheater

In a classroom, a student cheats on an exam, and their classmate, out of compassion, confesses to the act to protect the cheater from punishment. The teacher, knowing the classmate is innocent, proceeds to punish them instead.

Analysis: Allowing such a substitution does not correct the wrongdoing or ensure fairness. Instead, it undermines the teacher’s credibility and encourages others to avoid accountability for their actions.

Key Question: Does punishing the innocent classmate uphold the principles of justice in the classroom?

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. The Nature of Divine Justice Is Unique

Theologians might argue that divine justice differs fundamentally from human systems of justice. Since God is omniscient and operates beyond human understanding, His use of penal substitution may serve purposes that are morally perfect but incomprehensible to limited human reasoning.

- Key Point: Just because something appears unjust by human standards does not mean it is unjust from a divine perspective.

2. Jesus’s Willingness Validates the Sacrifice

The voluntary nature of Jesus’s sacrifice is often emphasized. Unlike a coerced substitute, Jesus willingly bore the punishment for humanity’s sins, making His act an expression of ultimate love and mercy rather than a forced injustice.

- Key Point: Theologically, justice is satisfied because Jesus chose to take the punishment, fulfilling the demands of both justice and grace.

3. Penal Substitution Reflects God’s Dual Nature

The concept of penal substitution is said to reconcile God’s dual nature as both perfectly just and infinitely merciful. By punishing sin through Jesus, God demonstrates His commitment to justice, while offering forgiveness reflects His mercy.

- Key Point: Without penal substitution, the balance between justice and mercy would be disrupted.

4. The Sacrificial System Foreshadows Atonement

The Old Testament’s sacrificial system is often cited as a precursor to Jesus’s atonement. In these rituals, animals symbolically bore the sins of the people, pointing to a future ultimate sacrifice.

- Key Point: Jesus’s death fulfills these foreshadowed acts, establishing a divine pattern of substitutionary atonement as central to God’s plan.

5. Humanity’s Guilt Is Collective

Some theologians argue that all of humanity bears collective guilt for sin, making Jesus’s substitution a communal act of redemption. This perspective sees justice in the collective nature of sin and atonement, rather than individual accountability.

- Key Point: Jesus’s death addresses the shared sinfulness of humanity, providing a means for universal reconciliation.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “The Nature of Divine Justice Is Unique”

If divine justice is fundamentally different from human systems of justice, it becomes incoherent and lacks any measurable framework. This makes divine justice arbitrary and unintelligible, rendering any claims about its superiority or reliability unverifiable.

- Key Rebuttal: Justice must operate within consistent principles to maintain credibility. A system that punishes the innocent while freeing the guilty undermines its functionality and reliability, regardless of appeals to mystery.

2. Response to “Jesus’s Willingness Validates the Sacrifice”

Willingness does not validate the transfer of consequences from the guilty to the innocent. For instance, if someone offers to serve a murderer’s prison sentence, the willingness of the substitute does not address the actions or accountability of the actual offender.

- Key Rebuttal: Systems based on accountability cannot function if those responsible for actions are not the ones facing their consequences, irrespective of voluntary substitution.

3. Response to “Penal Substitution Reflects God’s Dual Nature”

Balancing the goals of justice and mercy collapses if consequences are applied to the innocent instead of those responsible for the actions. This approach fails to address accountability and instead introduces contradictions in the application of consequences.

- Key Rebuttal: Accountability systems lose coherence when they redirect consequences away from those responsible, undermining any claims of consistency or effectiveness.

4. Response to “The Sacrificial System Foreshadows Atonement”

The Old Testament sacrificial system involved symbolic rituals, not the literal transfer of consequences from one party to another. Animals lacked agency and were used in acts of symbolic representation, not as substitutes for human accountability.

- Key Rebuttal: Shifting from symbolic acts to a direct transfer of consequences onto an innocent individual introduces inconsistencies that were not present in the original framework.

5. Response to “Humanity’s Guilt Is Collective”

Assigning collective guilt ignores the reality of individual responsibility. While individuals are influenced by collective environments, accountability systems cannot justifiably treat all individuals as equally responsible for actions they did not commit.

- Key Rebuttal: Treating humanity as a collective unit for assigning consequences introduces a breakdown in any functional accountability framework by failing to address individual contributions or lack thereof.

Clarifications

Culpability Cannot Be Transferred to Another Individual

1. Definition of Culpability

Culpability is the state of being morally or legally responsible for an act. It arises from:

- Intent: The mental decision to commit an act.

- Action: The physical execution of the act.

- Connection: The causal link between the offender’s actions and the harm caused.

Culpability inherently ties responsibility to the individual who possesses these three elements.

2. Premise 1: Culpability Is Intrinsically Linked to Agency

- Agency as a Precondition: Culpability is rooted in an individual’s capacity to make decisions and act upon them. Only the agent who acts (or fails to act) can be responsible for the outcomes of their actions.

- Moral and Legal Implications: Responsibility cannot be abstracted from the agent without severing the connection between action and consequence, rendering the concept of culpability meaningless.

3. Premise 2: Culpability Is a Function of Personal Intention and Action

- No Transferable Intent: The mental state (mens rea) of an individual cannot be shared or transferred. If someone other than the offender is punished, they do not share the intent or the causal relationship to the crime.

- Unique Accountability: Actions stem from the unique will of the individual. Punishing another violates the link between the will and the action.

4. Premise 3: Punishment Requires Justification Through Desert

- Desert Theory: A core justification of punishment is that it is deserved by the offender. If culpability is not present in the punished party, then punishment becomes inherently unjust.

- Substitution Undermines Justice: Punishing an innocent person creates a moral absurdity, as the punishment is no longer proportional to the crime.

5. Counterarguments and Refutations

- Counterargument 1: Voluntary Substitution

- Claim: If someone volunteers to take another’s punishment, culpability is not transferred but the punishment is carried out.

- Refutation: Punishment without culpability is not justice; it is an arbitrary infliction of harm. Consent to punishment does not create culpability, as culpability is tied to the crime, not the willingness to suffer for it.

- Counterargument 2: Cultural or Collective Responsibility

- Claim: Some cultures accept collective responsibility, where a group or family shares culpability.

- Refutation: Collective responsibility conflates guilt by association with culpability, which violates the principle of individual moral agency. A group cannot collectively share the intentionality or actions of the offender.

6. Conclusion: The Inalienability of Culpability

Culpability is fundamentally tied to the individual who possesses the agency, intent, and causal connection to a wrongful act. It cannot be transferred, because:

- Intent is not shared or transferable.

- Actions belong solely to the actor.

- Desert is a matter of individual accountability.

Any attempt to transfer culpability violates the principles of justice, fairness, and moral reasoning, reducing punishment to an arbitrary or coercive act rather than a justified response to wrongdoing.

Leave a comment