Consider the Following:

Summary: This post questions whether one should evaluate a proposed God’s character and actions before accepting that God as real, arguing that rational belief requires such scrutiny. It contends that any true deity would welcome honest inquiry rather than discourage it, and that assessing a God by their own standards rather than human standards is a circular and potentially misleading approach.

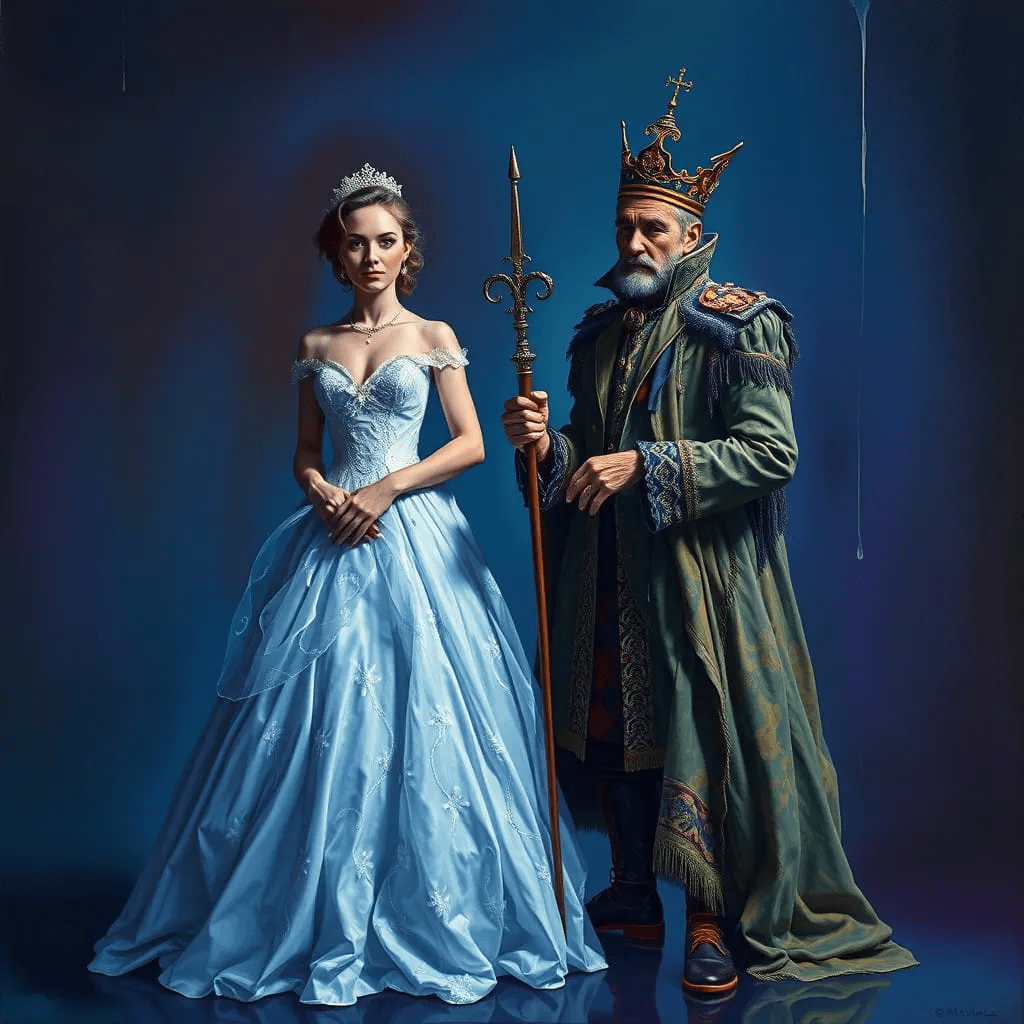

Imagine Cindy marries Roy simply because Roy claims to be a king. Without bothering to assess his character or actions, Cindy assumes Roy truly embodies the qualities of a king. Wouldn’t this seem naive? Wouldn’t it be wiser for Cindy to first verify Roy’s claims before committing her life to him? Now, picture Roy forbidding Cindy from questioning his character, arguing that any inconsistencies or oddities in his actions are beyond her understanding. He tells her, “My ways are not your ways,” asserting that her “lesser” intellect can’t grasp the depths of his character. Wouldn’t this prohibition against scrutiny cast doubt on Roy’s royal status in your mind?

Now, consider a proposed God who similarly prohibits scrutiny and demands unquestioning commitment. Should we accept such a God? Imagine a believer responds to your doubts with horror, saying, “How dare you question God! You lack the wisdom to understand his ways.” How would you respond?

As rational beings, our responsibility is to critically examine all available evidence, both confirming and disconfirming, before committing to a belief. A genuine search for truth should not place any questions off-limits. If an ideology discourages or forbids such questioning, it justifiably becomes suspect. A true ideology should withstand open inquiry and honest doubt.

The Need for Scrutiny in Divine Claims

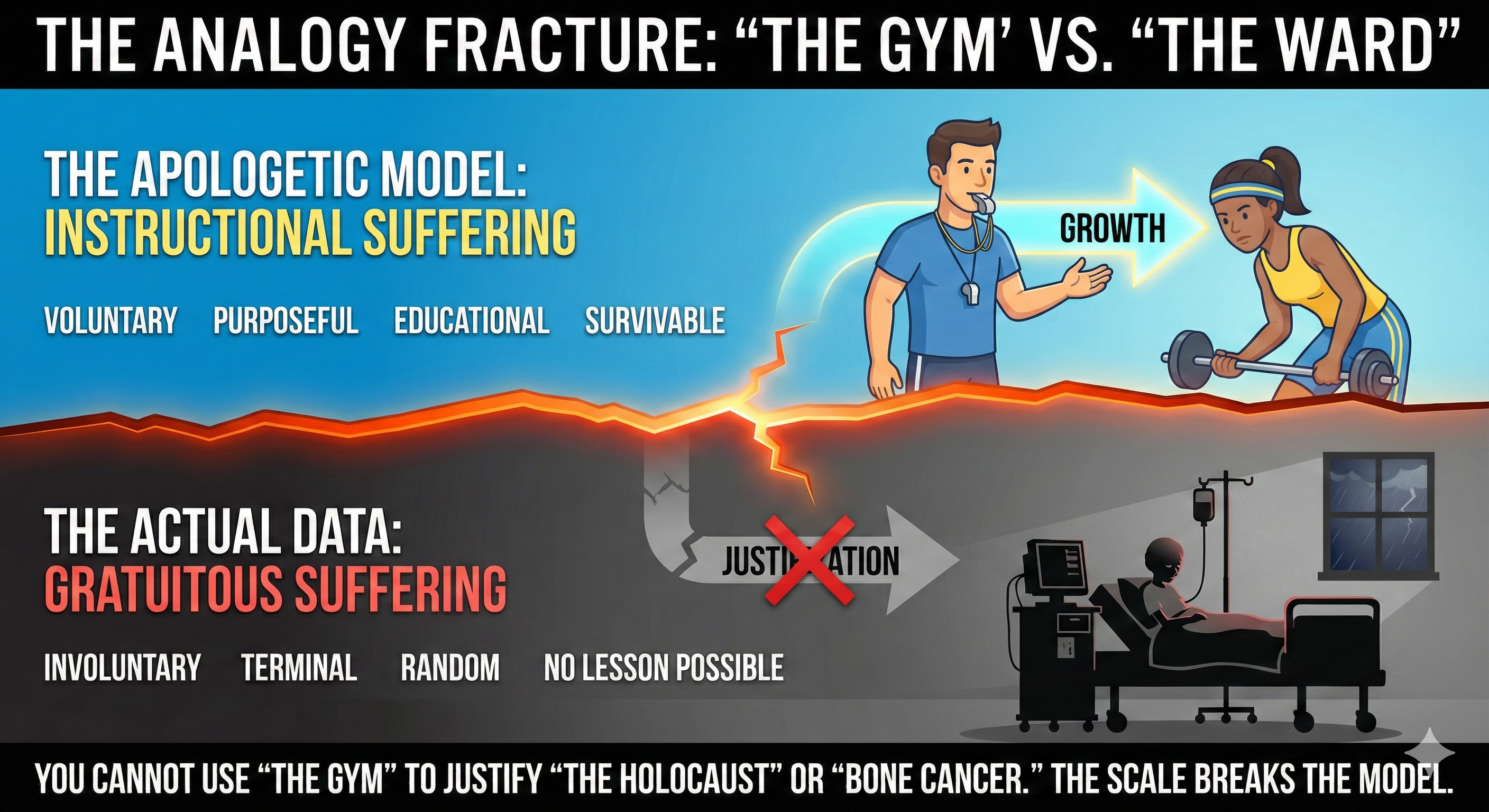

Why dare to question an alleged God’s claims? Simply put, as honest seekers, we must not abandon our duty to critically assess every claim, especially those about divinity. For each proposed God, it is our duty to examine how their supposed attributes and actions align with what we’d expect from an actual deity. Do we, for instance, expect that an actual creator of the universe would demand child sacrifice when offended? If not, we can reasonably consider such a candidate God improbable. If a God claims to be loving yet permits suffering among those he professes to love, such behavior suggests a lack of coherence with the concept of a benevolent deity. Dismissing our questions as “mysteries” to be accepted without understanding is a deflection that undermines genuine belief.

Wouldn’t it be rational to weigh every candidate God against the qualities we would expect in a genuine deity? Is it not irrational to do otherwise?

Does Love Look Like Hate, and Justice Like Injustice?

Could a truly loving God act in ways that seem unloving to us? Possibly. But rational inquiry demands only that our beliefs align with the evidence as we honestly perceive it. If we are to conclude that a certain God’s character is consistent with justice or love, we must arrive at this through an honest evaluation. If we judge a God improbable because his character contradicts our reasonable expectations, then, any “holy book” condemnations of our honest inquiry ascribed to that God renders that God logically incoherent since we reasonably expect any actual God to encourage rationality.

Is it not dishonest to embrace belief in a deity despite unresolved questions surrounding his character and the coherency of his nature? Could a truly just God condemn someone for questioning honestly? Wouldn’t a just God invite scrutiny, rather than deflect absurdities as “mysteries”?

The sincere seeker need not fear that a true God would condemn a critical examination of his nature.

Defaulting to an Unsubstantiated God’s Standards

Sometimes, believers argue, “How can you judge God without a divine standard of morality?” Yet these same individuals often reject other deities whose actions seem problematic under the standards of their favorite deity, whose standards they accepted without scrutiny. Is it surprising that all Gods pass scrutiny when judged under their own standards?

We need not blindly accept the standards of a deity we’re still evaluating to judge that deity by those standards. Nor need we abandon our obligation to scrutinize all Gods before we accept them. We responsibly use our own sense of justice, love, and patience to assess if a deity truly possesses those traits. Though fallible, our standards are all we have. To adopt a God’s standards without first examining their validity is to reverse the proper order of belief and assessment.

Once we accept that “love” might look like hate or “justice” like injustice by some divine mystery, how do we distinguish a true God from a deceitful and malevolent God or demon?

In conclusion, a commitment to assess the description and actions of all proposed Gods for logical coherence is far from arrogance and the risk of eternal damnation. Assessing Gods for logical coherence is the transparent responsibility of all honest seekers and and would be welcomed and encouraged by any actual rational God.

Don’t let others circularly convince you that you must defer to the very God in question on the matter of his logical coherence.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Rational Requirement for Belief in a God

- P1: Any true God would want belief in Him to be rational.

- P2: Rational belief requires evaluating all evidence relevant to an alleged deity.

- P3: A true God would want humanity to examine all evidence for any alleged deity.

- P4: Some versions of Christianity promote a God who discourages this examination.

- Conclusion: Therefore, some versions of Christianity promote a God who is unlikely to be actual.

Argument 2: The Duty of Scrutiny in Divine Claims

- P1: Honest seekers must critically assess every claim, especially those about divinity.

- P2: If a proposed God’s actions or attributes contradict expected divine qualities, we may reasonably doubt that God’s existence.

- P3: Some religious teachings discourage such scrutiny.

- Conclusion: Therefore, some religious teachings may support belief in a deity whose existence is unreasonable.

Argument 3: Coherency and the Nature of God

- P1: A truly just God would not condemn someone for honest questioning.

- P2: Some believers assert that doubting God’s character leads to damnation.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a God who condemns honest seekers for doubt contradicts the nature of a just God.

Argument 4: The Incoherence of “Divine Mysteries”

- P1: If “divine mysteries” allow love to appear as hate and justice as injustice, then these terms lack objective meaning.

- P2: Without objective meaning, we cannot distinguish a true God from a deceitful demon.

- Conclusion: Therefore, accepting “divine mysteries” that obscure objective meaning prevents us from distinguishing a true God from a deceitful demon.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Questioning Divine Justice

CLARUS: Chris, if your God is truly just and loving, shouldn’t we be free to question his actions without fear of punishment?

CHRIS: Clarus, that sounds like pride talking. Who are we to question God’s ways? His wisdom far exceeds our own, and we can’t expect to understand everything he does.

CLARUS: But if God’s wisdom is so great, shouldn’t his actions make more sense to us, not less? It seems odd that we’re asked to believe in a being whose actions often contradict the very qualities of justice and love we’re supposed to admire.

CHRIS: You’re thinking too humanly. God’s love might not always look like our version of love. Sometimes, what appears as suffering to us is part of a greater divine plan that we can’t comprehend.

CLARUS: So, you’re saying love could look like suffering and justice could look like injustice, all depending on some “mystery” we aren’t meant to understand?

CHRIS: Exactly! We have to trust that God knows what he’s doing, even if we can’t see it.

CLARUS: But if that’s the case, how can we tell the difference between a truly just God and a demon who just claims to be one? If “love” and “justice” can look like anything, then they mean nothing. We’d have no way to determine if we’re actually following a good being or a deceitful one.

CHRIS: Well, the Bible gives us God’s standards. We aren’t following some random deity; we’re following the God of Scripture.

CLARUS: But that’s circular, isn’t it? You’re judging other gods as false based on the standards of your own God, without any objective measure. Isn’t that like me declaring that only my friend’s definition of “honesty” is valid, so anyone else must be dishonest?

CHRIS: But Clarus, if you use your own understanding, you’ll inevitably misunderstand divine things. That’s why you have to submit to God’s standards before you can truly understand his nature.

CLARUS: But that’s backwards. I’d need to see that this God’s actions match basic standards of justice and love before I believe. You wouldn’t marry someone without verifying their character, would you?

CHRIS: I see your point, but belief requires faith, and faith is trusting in what we can’t fully see or understand.

CLARUS: I get that, but blind faith seems risky. If an ideology discourages questioning, it’s usually hiding something. If God is just and good, wouldn’t he welcome honest inquiry rather than condemn it?

CHRIS: Perhaps, but at some point, faith requires humility to accept things beyond our understanding.

CLARUS: Humility, yes, but not at the cost of reason. A God who would condemn honest questioning seems more insecure than loving. If he truly values justice, he’d want us to pursue truth—even if that includes questioning him. Right?

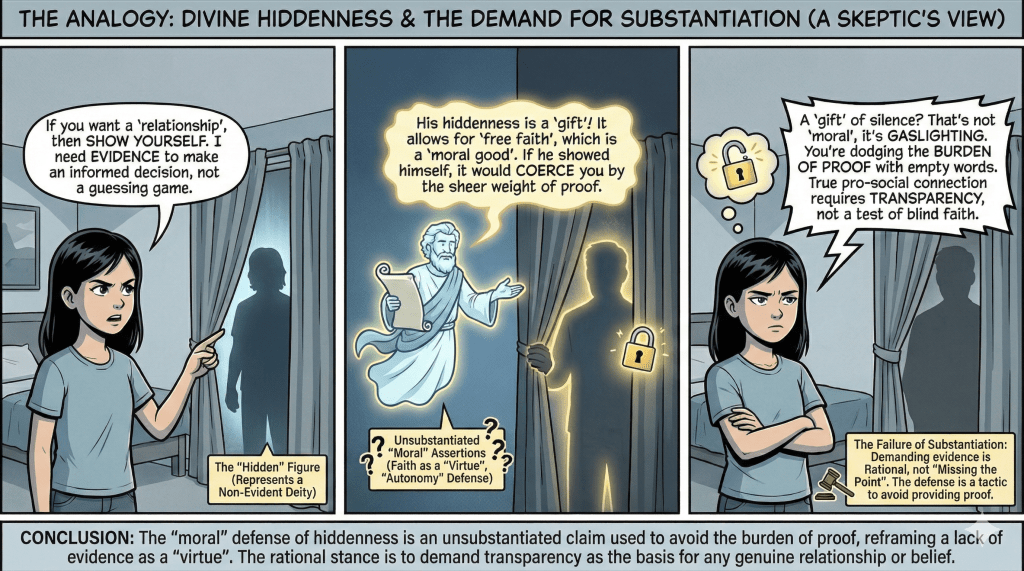

Imagine asking a woman to accept that a man, who is hiding behind her bedroom curtains, is worthy of her love.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Blind Judge

Imagine a judge who is instructed to assess cases of justice but is told that justice could look like injustice or cruelty. If any action could theoretically be justified as “just,” then justice loses its objective meaning, and no measure of justice remains through which the judge’s decisions can be assessed. Similarly, if divine mysteries allow love to resemble hate or justice to appear as injustice, then distinguishing a true God from a deceptive force becomes impossible.

Analogy 2: The Deceptive Leader

Suppose a politician assures people of their integrity but insists that honesty may sometimes look like deception under certain “higher purposes.” Without a stable, objective meaning for honesty, it becomes impossible to hold this leader accountable. Likewise, if divine mysteries allow terms like love and justice to have no fixed meaning, distinguishing a benevolent God from a malicious being becomes untenable.

Analogy 3: The Fake Currency

Imagine receiving currency that a bank claims may look like counterfeit but is still “genuine” under certain hidden conditions. If “genuine” currency can resemble fake money, then the concept of authenticity loses its value, and you can no longer trust the currency. In the same way, if divine mysteries allow justice to resemble injustice, the very concept of a just God loses meaning, preventing us from discerning true divine goodness from deception.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Divine Transcendence Beyond Human Understanding

Theologians might argue that God’s nature is transcendent and therefore surpasses human understanding. What may appear as injustice or hate to human minds might actually be expressions of a higher divine love or justice that we simply cannot fully comprehend. In this view, our conventional terms are limited and cannot encompass the fullness of divine reality.

2. Mystery as a Test of Faith

Another theological response might emphasize that divine mysteries serve as a test of faith for believers. By trusting that God is good even when his actions seem to contradict human moral standards, believers demonstrate faith in his ultimate wisdom and benevolence. This perspective holds that faith itself is strengthened by accepting that God’s ways are beyond our moral frameworks.

3. Redefinition, Not Rejection, of Moral Terms

Theologians may contend that divine mysteries do not reject objective meaning but rather redefine it within a divine context. From this standpoint, terms like love and justice retain their objective meanings, but these meanings are enhanced or broadened by God’s infinite nature. Thus, human understanding of love and justice is considered a partial reflection of God’s perfect qualities, rather than a complete framework for evaluating divine actions.

4. Historical Context of Divine Revelation

Some theologians argue that God’s actions must be viewed within the historical context in which they were revealed. They might assert that certain actions attributed to God in religious texts, which seem harsh or unjust by modern standards, were appropriate for the culture and moral understanding of that time. This perspective suggests that divine actions reflect an adaptive approach to guiding humanity, rather than a fixed adherence to modern ethical standards.

5. Moral Growth Through Divine Mystery

Another response might hold that divine mysteries prompt believers to engage in moral reflection and growth. By grappling with actions or attributes that seem contradictory to human ethics, believers are encouraged to deepen their understanding of moral complexities. This view interprets divine mystery not as moral relativism but as a challenge to grow spiritually and develop a more nuanced comprehension of love and justice.

- See “Clarifications” for an explanation of the reference to morality.

Counter-Responses

1. Limits of Divine Transcendence as a Rational Justification

While divine transcendence is often cited as a reason why God’s actions are beyond human understanding, this response can undermine a behavioral assessment and objective meaning. If love and justice lose their fixed definitions due to divine transcendence, then these concepts are rendered ambiguous and can justify any action. For a term like justice to be meaningful, it must align with certain objective principles; otherwise, it risks becoming a vacuous label that supports any arbitrary claim about God’s nature.

2. Faith Testing and the Need for Coherent Moral Standards

Claiming that divine mysteries are a test of faith implicitly assumes that faith is more valuable when it disregards moral coherence. However, rational belief requires a degree of consistency between claims of goodness and observable actions. If God is depicted as both just and benevolent, then actions that appear as injustice or cruelty call for justification that aligns with these terms. Otherwise, the test of faith becomes a test of credulity, requiring believers to abandon their moral intuitions without any rational basis for moral trust.

3. Redefining Terms Erodes Objective Meaning

While theologians argue that divine mysteries merely broaden the meanings of terms like love and justice, this redefinition dilutes their objectivity. If love or justice can mean one thing to humans and another to God, then these terms lose their stability and fail to guide us in recognizing moral qualities. For objective moral standards to hold, they must be universally intelligible; without this, distinguishing a benevolent God from a malevolent being becomes impossible, as any behavior could be labeled just or loving under an undefined divine perspective.

4. Historical Context Doesn’t Excuse Moral Contradictions

Appealing to historical context suggests that God’s nature adapts to cultural morals rather than transcends them, which contradicts the idea of eternal moral standards. If God’s actions are interpreted as just for one era and unjust by today’s standards, then moral relativism is unavoidable, even in divine contexts. A truly just and loving God would act in ways that reflect consistent moral principles across all times and cultures, rather than adapting to the limitations of each historical period.

5. Divine Mystery Should Not Compromise Moral Clarity

While divine mysteries are often invoked to compromise moral clarity. If believers are expected to grow through moral ambiguities attributed to God’s actions, this growth becomes subjective and unpredictable without an objective moral foundation. Mysteries that erode clear standards for love and justice lead to moral confusion rather than enlightenment, as they provide no stable moral framework for believers to genuinely distinguish good from evil.

Clarifications

The inclusion of the term “morality” in the article above is merely a reductio ad absurdum tool to explore the internal coherence of Christianity and does not imply actual morality exists.

From a moral non-realist perspective, the term “morality” is not taken as an indicator of any objective moral truths or inherent moral realm. Instead, it is used as a reductio ad absurdum device to assess the internal logic of Christian doctrines that claim moral authority and ethical absolutes. In this view, the invocation of “morality” serves purely as a conceptual tool, adopted to highlight potential inconsistencies within a framework that professes absolute moral standards but may fail to uphold them in practice or theology.

For a moral non-realist, moral terms like “good,” “evil,” “justice,” and “love” are understood as expressions of human emotions, cultural conventions, or social agreements without intrinsic truth-value. By temporarily engaging with the language of morality as defined by Christian doctrine, the moral non-realist can question the coherence of these doctrines by examining whether Christianity’s moral claims remain logically consistent within its own terms. However, this does not imply an endorsement of objective morality; rather, it acknowledges that Christianity operates within a moral framework it purports as real and binding.

Thus, when analyzing Christianity’s ethics, a moral non-realist employs moral language only to reveal internal contradictions or logical gaps. The aim is not to affirm any moral truths but to demonstrate that Christianity must, at minimum, adhere to the standards it prescribes if it is to be self-consistent. The use of morality here is, therefore, instrumental and hypothetical—it is a lens through which internal coherence can be evaluated without conceding the existence of moral facts.

That said, the author does encourage those who feel they can articulate a moral system that does not reduce to mere emotions or blind obedience to present coherent grounding for that moral system.

The tactic of feigned horror and the exclamation, “How dare you judge God!” serves as a form of social and intellectual intimidation designed to halt inquiry by appealing to authority and devotion rather than reason.

When someone challenges God’s actions or character, this response implicitly assumes that questioning divine authority is arrogant or blasphemous, attempting to shift the focus from the substance of the critique to the presumed attitude of the questioner. By suggesting that humility equates to unquestioning acceptance, this tactic discourages believers from engaging with potential contradictions or logical gaps within their faith’s moral framework.

For a moral non-realist or a rational inquirer, the notion that one must “humble oneself” before God by suspending all questioning undermines the pursuit of truth and internal coherence. If God’s nature is truly just and benevolent, then genuine inquiry and rational reflection should not be seen as defiant but as sincere efforts to establish the logical coherence of the alleged deity and accompanying morality. Feigned horror implies that faith requires submission without scrutiny, thus sidelining critical examination and potentially allowing for moral contradictions to remain unaddressed. Ultimately, this tactic diverts from a reasoned discussion and introduces an atmosphere where devotion replaces clarity as the measure of faithfulness, which can render belief more about loyalty than logical integrity.

◉ Formalization:

1) Language Domains

— Set of proposed God-concepts. Variables

and

refer to specific concepts within this set.

— Constant representing the honest seeker.

Predicates on

— Predicate meaning “

is coherent” (internally consistent without logical contradictions).

— Predicate meaning “

is consistent with its attributed actions/record” (its descriptions and actions do not conflict).

— Predicate meaning “

is desirable” (allegiance to g promotes human well-being or trustworthiness).

— Predicate meaning “

is open to independent evaluation” (no prohibition on questioning).

— Predicate meaning “

is circular” (assessment of

depends only on g’s own authority).

— Predicate meaning “

is worthy of worship or allegiance.”

— Predicate meaning “commitment to

is high-stakes” (significant consequences for the seeker).

Policies attached to a concept

— Predicate meaning “

forbids independent questioning.”

— Predicate meaning “

requires only its own standards to assess itself.”

Doxastic / Normative

— Predicate meaning “seeker

believes in or commits allegiance to

.”

— Predicate meaning “seeker

has critically evaluated

on the relevant dimensions.”

— Predicate meaning “it is rationally permissible for seeker

to believe

.”

Deontic operator (relative to )

— Means “seeker

ought that φ.” This marks obligation claims.

2) Core Axioms / Premises

— P1 (High-stakes duty): For any entity , if commitment to x is high-stakes, then seeker

ought to evaluate

.

— P2 (Theistic stakes): All God-concepts in set are high-stakes commitments.

— P3 (What “evaluated” entails): If seeker has evaluated

, then

must be coherent, consistent with its record, desirable, open to independent evaluation, and not circular.

— P4 (Failure bars rational permission): If fails on coherence, consistency, desirability, openness, or non-circularity, then it is not rationally permissible for

to believe

.

— P5 (Permission requires evaluation): If it is rationally permissible for to believe

, then

must have evaluated

.

— P6 (Worthiness welcomes scrutiny): If is worthy of worship, then it must be open to independent evaluation.

— Contraposition of P6: If is not open to independent evaluation, then

is not worthy of worship.

— P7 (Belief aiming at allegiance presupposes worthiness): If believes in

, then

must be worthy of worship.

— P8a (Forbidding ⇒ closed): If forbids independent questioning, then

is not open to evaluation.

— P8b (Self-standard ⇒ circular): If allows only its own standards for assessment, then

is circular.

— Optional: P8 can be defined as the conjunction of P8a and P8b.

— P9 (Plurality trigger): If there exists another God-concept in G that is different from

and competes with it, then

ought to evaluate

.

— P10 (Stability of permissibility): Even if belief in is properly basic

and

ought to evaluate

, then evaluation should still occur after belief formation.

3) Immediate Derivations

— D1 (Obligation to evaluate God-concepts): From P2 and P1, for all God-concepts in G, seeker

ought to evaluate

.

— D2 (What permission entails): From P5 then P3, if it is rationally permissible for to believe

, then

must be coherent, consistent with its record, desirable, open to independent evaluation, and not circular.

— D3a (Forbid defeats permission): From P8a and P4, if forbids questioning, then it is not open to evaluation, and therefore it is not rationally permissible to believe

.

— D3b (SelfOnly defeats permission): From P8b and P4, if requires only its own standards for assessment, then it is circular, and therefore it is not rationally permissible to believe

.

— D4a (Closed concepts are unworthy): From the contrapositive of P6, if is not open to evaluation, then it is not worthy of worship.

— D4b (Belief presupposes worthiness): From P7, if believes in

, then

must be worthy of worship.

Conclusion from D4: If is closed to evaluation (

), then it fails the worthiness requirement for belief, so belief is blocked.

— D5 (Headline norm): For every in

, seeker

ought to evaluate

, and if

fails in coherence, consistency, desirability, openness, or non-circularity, then it is not rationally permissible to believe

.

4) Fitch-style Proof of the Central Theorem

Goal 1:

— Target claim A: For every God-concept g, seeker ought to evaluate

.

— Target claim B: For every God-concept g, if is incoherent, inconsistent with its record, undesirable, closed to scrutiny, or circular, then belief in

is not rationally permissible for

.

— From P2: All God-concepts are high-stakes for the seeker.

— From P1: Anything high-stakes should be evaluated by .

— Begin universal generalization by reasoning with an arbitrary but fixed .

— Instantiation of P2 for the arbitrary : commitment to

is high-stakes.

— Modus ponens on P1 with H(g): therefore ought to evaluate

.

— Universal generalization: since was arbitrary, the obligation to evaluate holds for all

.

— From P4 directly: the failure-conditions bar rational permission for any ; this establishes Target claim B.

— Goal 1 established: both the universal obligation to evaluate and the failure-bar on permission are derived.

Goal 2 (Corollaries for prohibitions/circularity):

— Target claim (a): If forbids independent questioning, then it is not rationally permissible for

to believe

.

— Target claim (b): If demands only self-referential standards, then it is not rationally permissible for

to believe

.

— Assume, for conditional proof of (a), that forbids questioning.

— From P8a: forbidding implies lack of openness.

— Modus ponens: thus is not open to independent evaluation.

— From P4: any failure on the listed dimensions defeats rational permission.

— Modus ponens using the specific disjunct : rational permission is defeated; hence

.

— Assume, for conditional proof of (b), that requires only its own standards.

— From P8b: self-standard implies circularity.

— Modus ponens: thus is circular.

— From P4: circularity is among the defeat conditions.

— Modus ponens using the specific disjunct Cir(g): rational permission is defeated; hence .

— Goal 2 established: prohibitions and self-referential standards each defeat rational permission.

Goal 3 (Unworthiness under prohibition):

— From the contraposition of P6: lack of openness entails lack of worthiness.

— From P8a: forbidding questioning implies not open.

— Hypothetical syllogism on the two prior lines: a forbidding concept is unworthy.

— From P7: belief presupposes worthiness.

— If forbids questioning, then it cannot meet the worthiness condition required by belief.

— Goal 3 established: prohibitions undermine worthiness and thereby block belief that presupposes worthiness.

5) Compact Sequent Summary

— From P1 and P2, it follows that ought to evaluate every God-concept.

— From P4, any failure on coherence, consistency, desirability, openness, or non-circularity defeats rational permission.

— From P8a with P4, forbidding evaluation defeats rational permission.

— From P8b with P4, self-referential standards defeat rational permission.

— From P6 (contraposed) and P7, forbidding undermines worthiness while belief requires worthiness; thus forbidding defeats belief-worthiness.

6) Optional “Properly Basic” Add-on

— Premise: s’s belief in begins as properly basic (non-inferentially formed).

— From P9: the existence of competing peer concepts triggers an obligation to evaluate .

— When the plurality condition is met, is obligated to evaluate

even if belief was properly basic.

— From P10: proper basicality does not cancel the duty to evaluate; evaluation proceeds after belief onset.

— By D2, continued rational permissibility requires coherence, consistency with record, desirability, openness, and non-circularity.

Conclusion: even with proper basicality, plural competition and high stakes sustain a duty to evaluate, and permission still requires

— Properly basic onset does not exempt from meeting the same rational-permission profile.

7) Plain-English Gloss

— For any proposed God-concept , the honest seeker

ought to evaluate it; and if

is incoherent, inconsistent with its record, undesirable, closed to scrutiny, or defended circularly, then believing

is not rationally permissible.

Christian Apologists Group Responses

◉ These quotes are some of the most salient, representative quotes in response to this issue from a Facebook group called “Christian Apologetics.” This group consist of quite civil and well-educated apologies, many of them, pastors, or ministers.

Not all of the responses were problematic. The list below contains only the clearly flawed responses, posted here for educational purposes. The last check revealed that there were a total of 340 comments in the thread.

- “God’s ways are higher than ours.”

Why it fails: Appeal to mystery. Evades the question about textual clarity and humanitarian knowledge.

- “Other gods are fallen angels or Satan himself.”

Why it fails: Assumes the truth of Christianity without argument. Does not address the content critique.

- “You are not a serious seeker.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem. Dismisses the arguer instead of the argument.

- “You’re in an Apologetics group.”

Why it fails: Irrelevant procedural point. No engagement with the theological critique.

- “It’s illogical to claim we can judge God.”

Why it fails: Begs the question. The original post is questioning whether such a God is worthy of belief.

- “Apologetics is defending, not questioning.”

Why it fails: Focuses on method, not content. Dodges the criticism.

- “We don’t have to question our beliefs to defend them.”

Why it fails: Evades the issue of whether unexamined belief deserves defense.

- “You’re dictating how God should act.”

Why it fails: Mischaracterizes the post. It questioned the internal coherence of God’s supposed traits.

- “God tells us who he is in the Bible.”

Why it fails: Circular reasoning. Uses the text under critique to justify the critique.

- “God is worthy not by any standard, but because He is God.”

Why it fails: Divine command theory. Assumes authority without epistemic justification.

- “Science happened for me because of God.”

Why it fails: Post hoc fallacy. Personal narrative doesn’t engage with the general critique.

- “A true seeker will find the truth.”

Why it fails: No True Scotsman. Reframes criticism as insincerity.

- “You judge God by human standards.”

Why it fails: Avoids internal coherence checks. Shifts burden away from explanatory adequacy.

- “You assume God’s unworthiness means he doesn’t exist.”

Why it fails: Straw man. The argument critiques divine authorship, not mere existence.

- “You must show worthiness and existence are logically distinct.”

Why it fails: The original post does not argue they are equivalent, but critiques the coherence of worship-worthiness.

- “You only want to win a debate.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem. Assumes motive instead of answering the challenge.

- “You have been told enough.”

Why it fails: Evasion. Dismisses continued engagement without addressing content.

- “I came to faith through research.”

Why it fails: Personal testimony. Doesn’t engage with the systemic critique.

- “Faith isn’t blind.”

Why it fails: Doesn’t explain why faith remains credible without basic empirical grounding.

- “You have a Western intellectual mind.”

Why it fails: Red herring. Impugns methodology rather than arguments.

- “God doesn’t owe us anything.”

Why it fails: Avoids the original question of whether a compassionate deity would act.

- “The Bible’s clarity is proven through faith.”

Why it fails: Circular. Uses faith to validate what is under scrutiny.

- “You can’t limit God to human logic.”

Why it fails: Special pleading. Exempts God from the standards applied to all other truth claims.

- “You just don’t want God to be real.”

Why it fails: Psychological projection. Does not refute the argument.

- “You sound angry at God.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem. Emotional speculation about the arguer.

- “I trust God’s plan even if I don’t understand it.”

Why it fails: Appeal to ignorance. Defers to mystery rather than engaging evidence-based criticism.

- “We can’t expect to understand everything with our limited minds.”

Why it fails: Special pleading. Dismisses rational evaluation.

- “Atheists always twist the Bible.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem and sweeping generalization.

- “You wouldn’t believe even if God appeared to you.”

Why it fails: Mind-reading fallacy. Avoids the substantive argument.

- “The Bible isn’t a science textbook.”

Why it fails: Straw man. The critique is not that it should be, but that it omits crucial life-saving knowledge.

- “Your logic is flawed because it lacks faith.”

Why it fails: Category error. Faith and logic are different epistemic tools.

- “God works in mysterious ways.”

Why it fails: Appeal to mystery. Non-response.

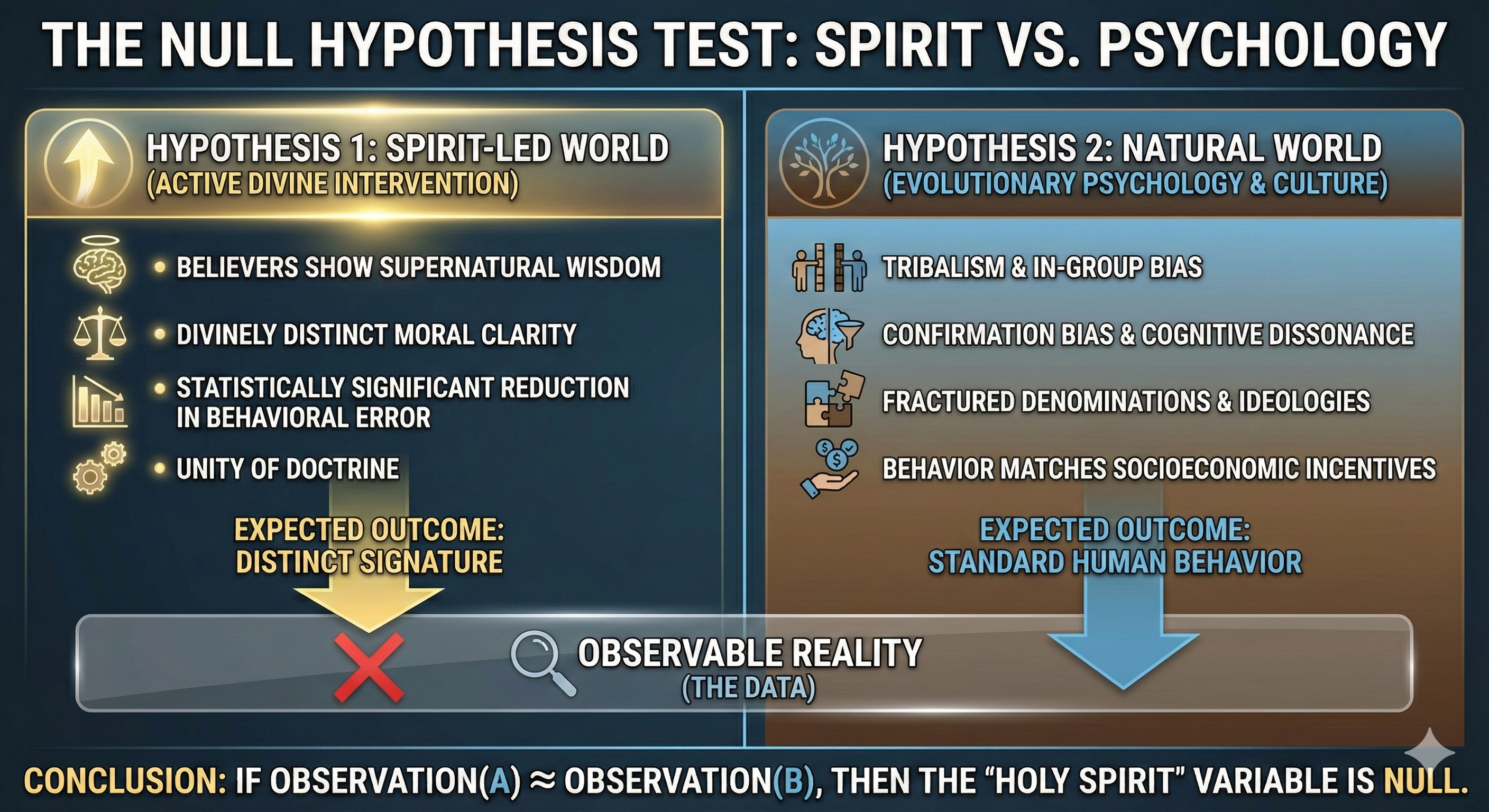

- “You need the Holy Spirit to truly understand.”

Why it fails: Unfalsifiable and excludes nonbelievers from rational inquiry.

- “God’s justice is perfect even if we can’t see it.”

Why it fails: Circular and unverifiable.

- “You’re using man’s reasoning, not God’s.”

Why it fails: Special pleading. Evades shared reasoning standards.

- “Why should God care about disease? It’s part of the fall.”

Why it fails: Theodicy deflection. Avoids the question of divine authorship.

- “All truth is God’s truth.”

Why it fails: Tautological. Doesn’t address omissions in Scripture.

- “Your question shows you don’t fear God.”

Why it fails: Tone policing. Doesn’t respond to substance.

- “You’re reading with a hardened heart.”

Why it fails: Psychological attack. Avoids the argument.

- “God has revealed all we need.”

Why it fails: Assertion without justification. Ignores the critique’s examples.

- “Truth isn’t determined by logic but by revelation.”

Why it fails: Rejects critical scrutiny in favor of dogma.

- “God gave us brains, but not to question Him.”

Why it fails: Contradictory reasoning. Undermines human inquiry.

- “You’re arrogant to think you could judge the Creator.”

Why it fails: Fallacy of hubris. Shifts focus from the argument to tone.

- “Spiritual things are spiritually discerned.”

Why it fails: Exclusionary epistemology. Dismisses reasoned critique.

- “Faith begins where reason ends.”

Why it fails: Abandons logic. Doesn’t respond to the argument.

- “Many have come to Christ through that same Bible.”

Why it fails: Popularity fallacy. Doesn’t address content.

- “Your questions are dangerous.”

Why it fails: Anti-intellectualism. Refuses engagement.

- “Doubt is the devil whispering.”

Why it fails: Demonizes skepticism. Avoids rational debate.

- “Only God knows what’s best.”

Why it fails: Appeal to authority without justification.

- “His silence is part of the test.”

Why it fails: Theodicy by obfuscation. Doesn’t respond to the central concern.

Leave a reply to J Cancel reply