Consider the Following:

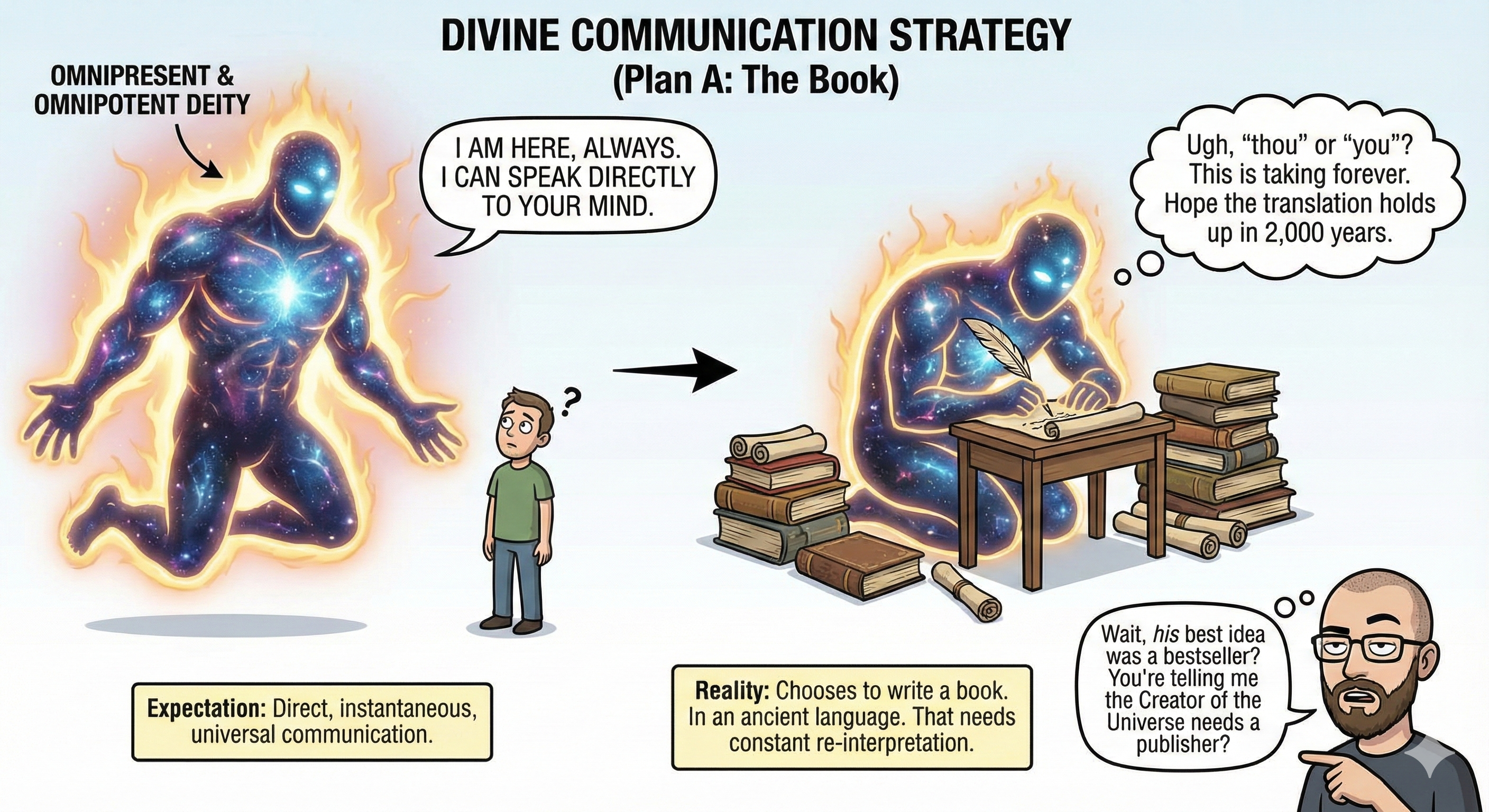

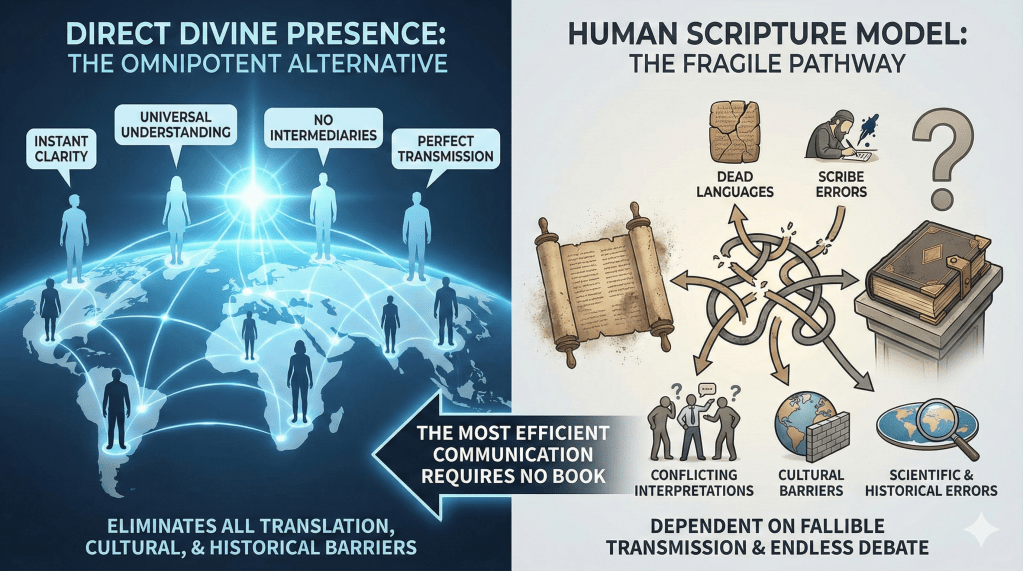

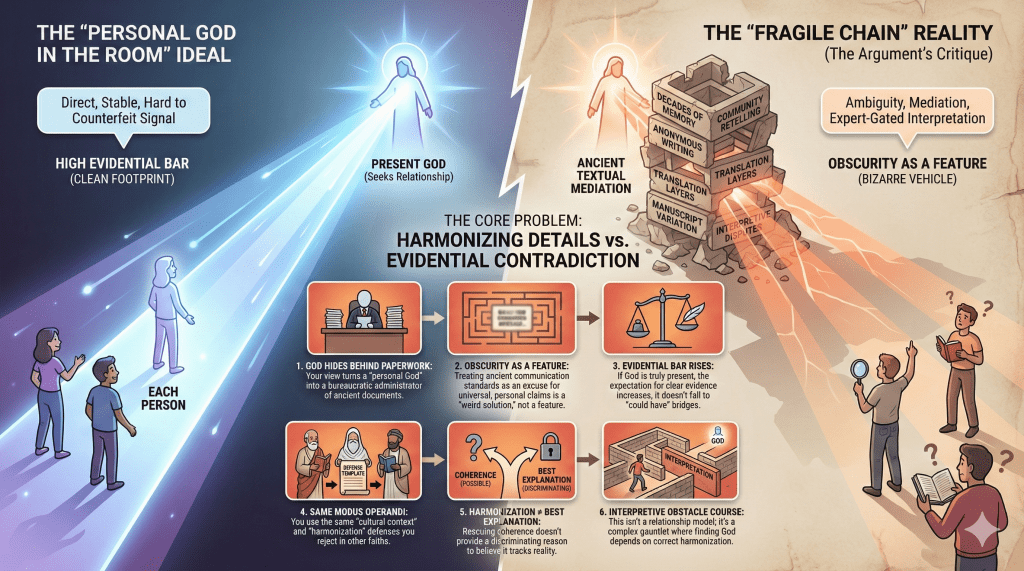

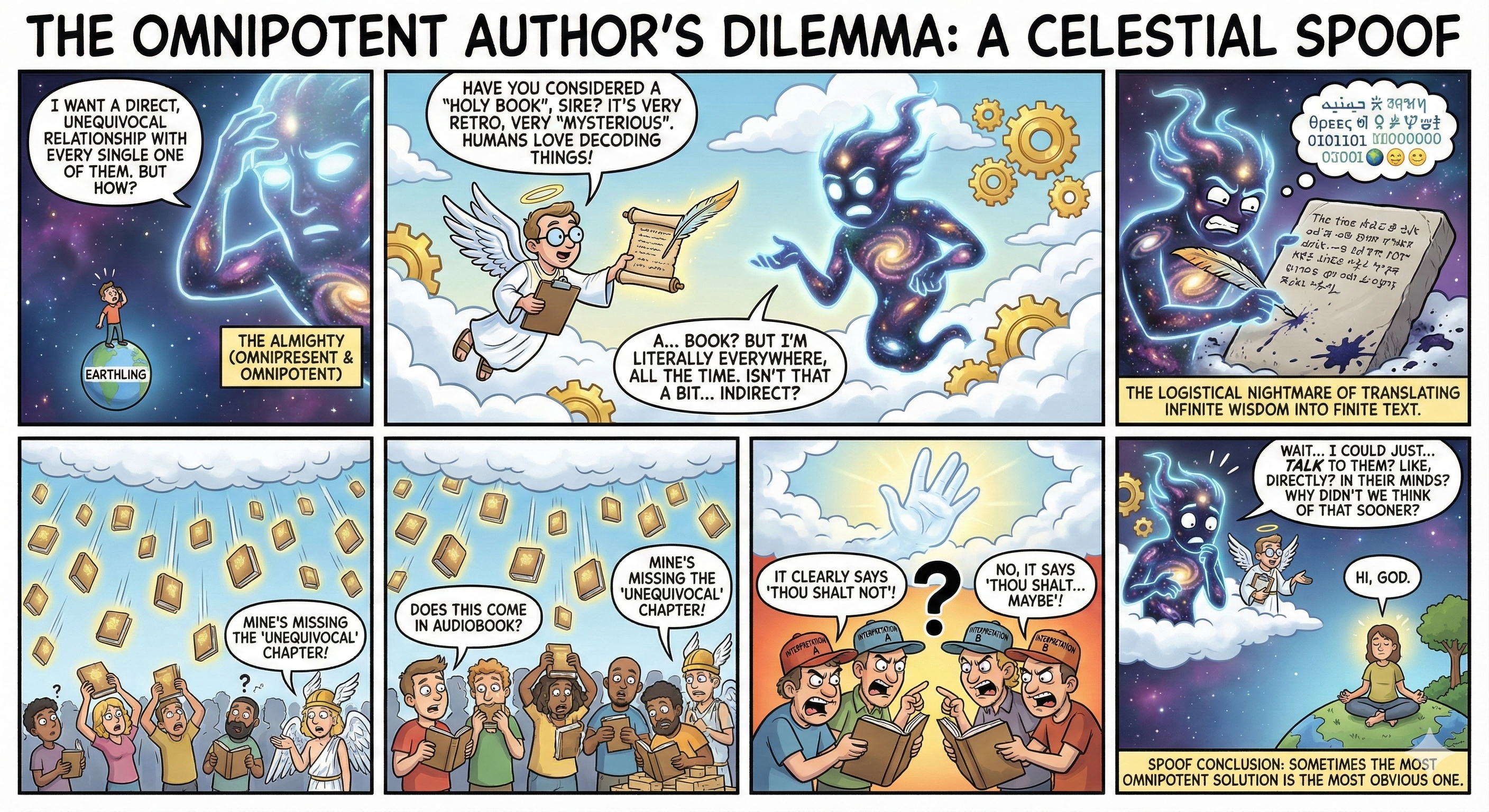

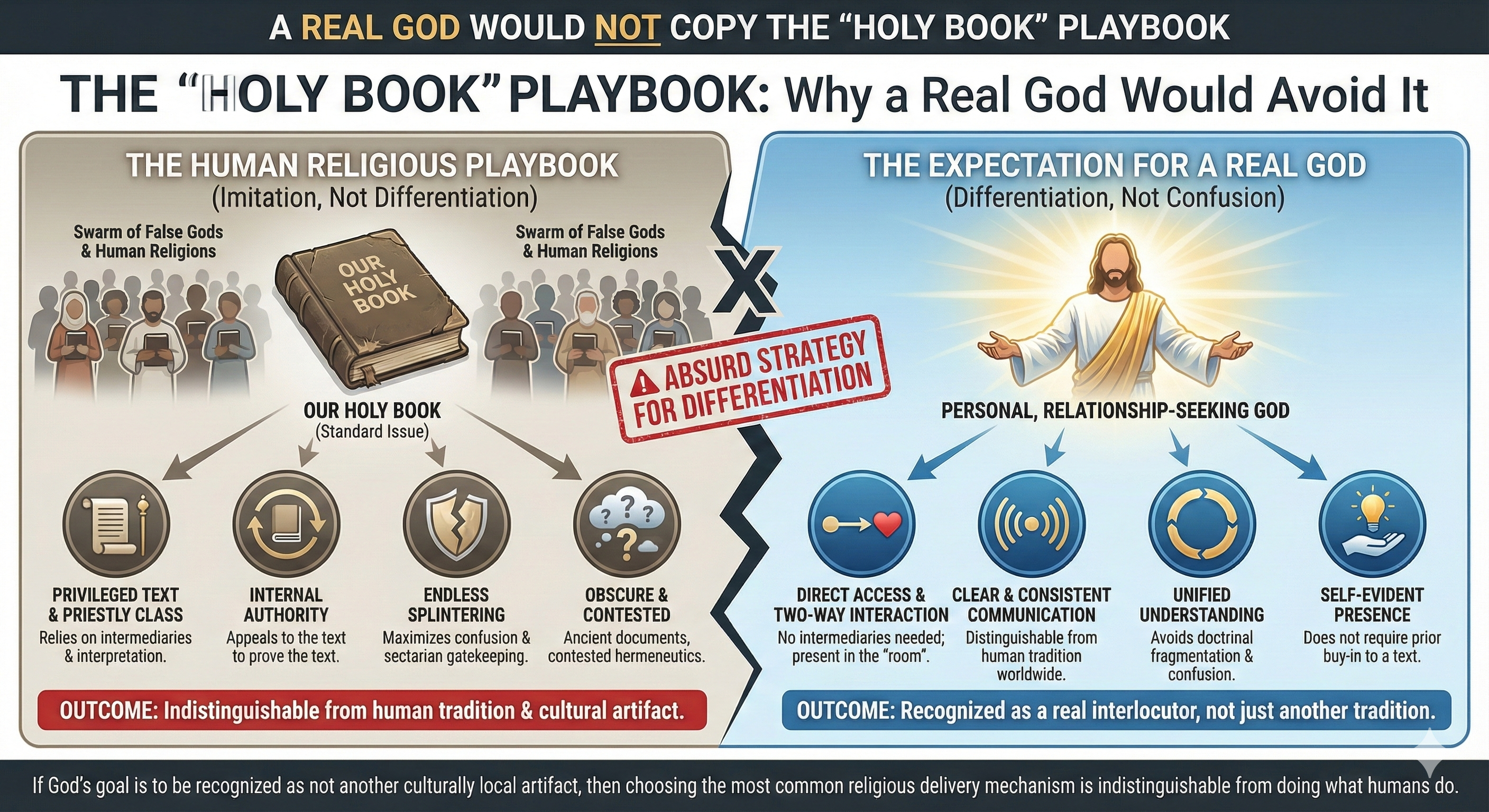

Summary: Why would a personal God who desires a relationship rely on a book for revelation rather than direct encounters, especially given claims of omnipresence and omnibenevolence? This content argues that divine hiddenness and the reliance on indirect methods make God indistinguishable from other deities, casting doubt on the sufficiency of evidence and the authenticity of faith that discourages open inquiry.

Imagine a woman named Julie who discovers a compelling book describing an allegedly real man who loves her deeply. According to the book, this man remains invisible yet is supposedly always within arms reach. Julie learns that unless she believes in his presence, she risks rejecting his love, resulting in his eternal anger. After years of carefully reading the book, Julie never actually encounters the man. She is left with only the romantic promises in the book instead of the actual embrace of the man. Rationally, what can Julie rationally conclude about these claims?

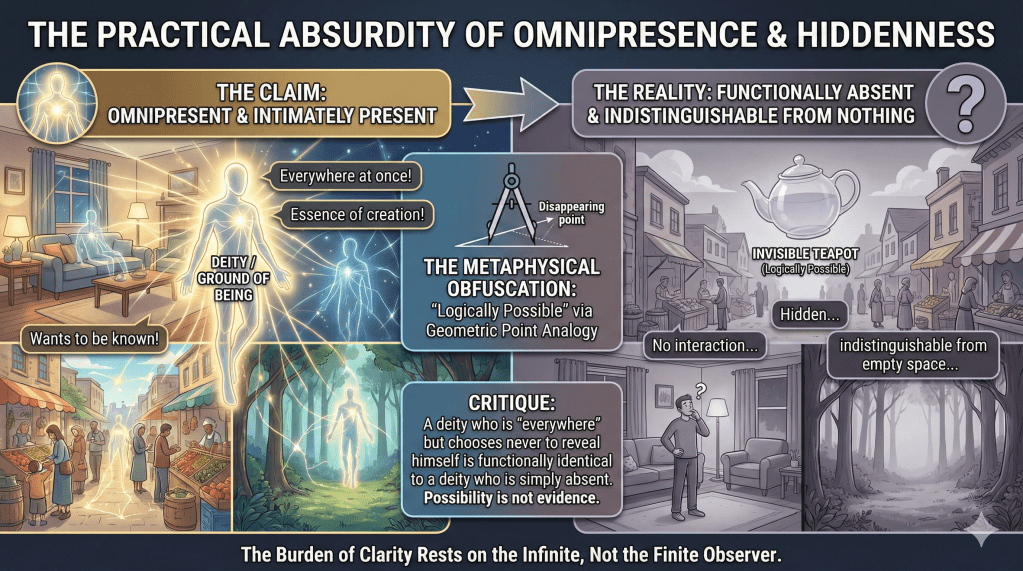

Similarly, what should we conclude about a book that claims an omnipresent, loving God exists but never provides a direct encounter? Many believers in other proposed Gods also report vague feelings of divine presence, so why is there no clear, distinguishing interaction?

The Christian God is said to possess these qualities:

- Omnipresence: He is beside us, observing us.

- Desire for a Personal Relationship: He seeks connection with each of us.

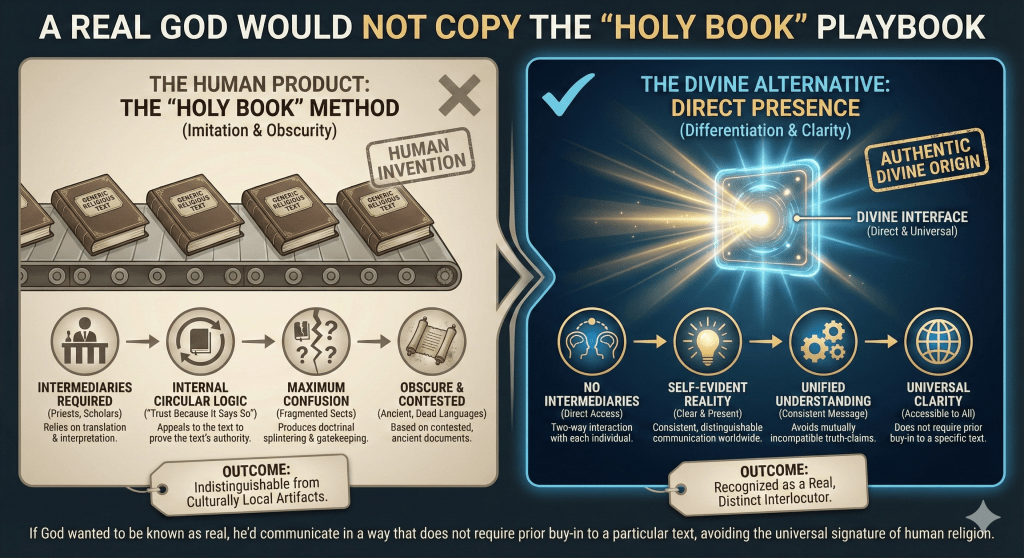

Why, then, would such a God avoid clear, face-to-face interaction with us? What would prevent a truly omnipotent and relational God from fully revealing himself? This silence mirrors the modus operandi of other deities. Yet the Bible portrays its God as jealous and easily angered when people turn to alternative gods (Numbers 25:9). Why would a unique God rely on the same hidden approach used by countless other deities?

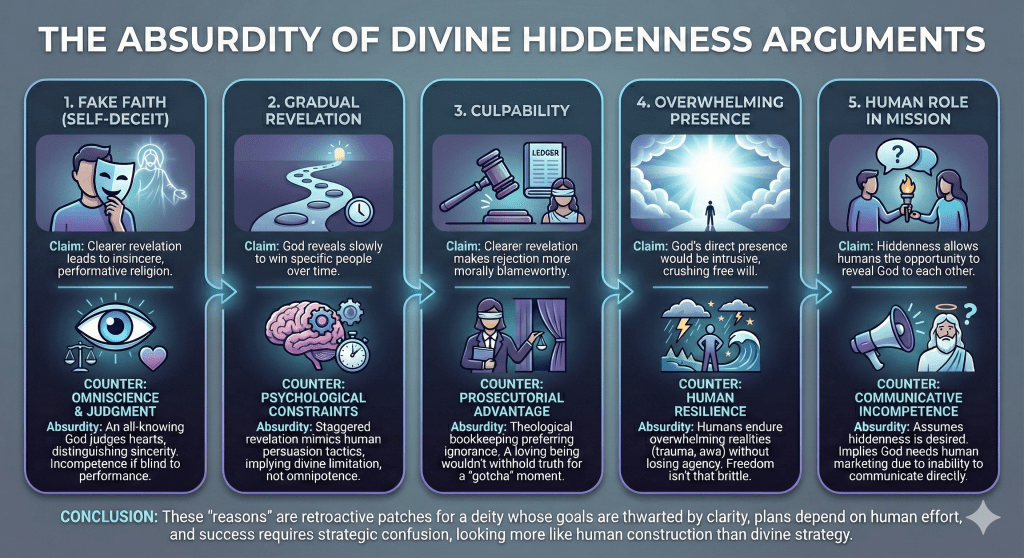

Two arguments are often offered:

- Revealing Himself Would Violate Human Free Will. Does this follow logically? If a suitor appears directly to someone, does that undermine their freedom to accept or reject them? Recognition of someone’s presence is separate from accepting their advances. How could one truly accept a relationship with someone whose existence remains uncertain? If God is omnipotent and desires our love, why wouldn’t he promptly remove any barriers to belief and worship?

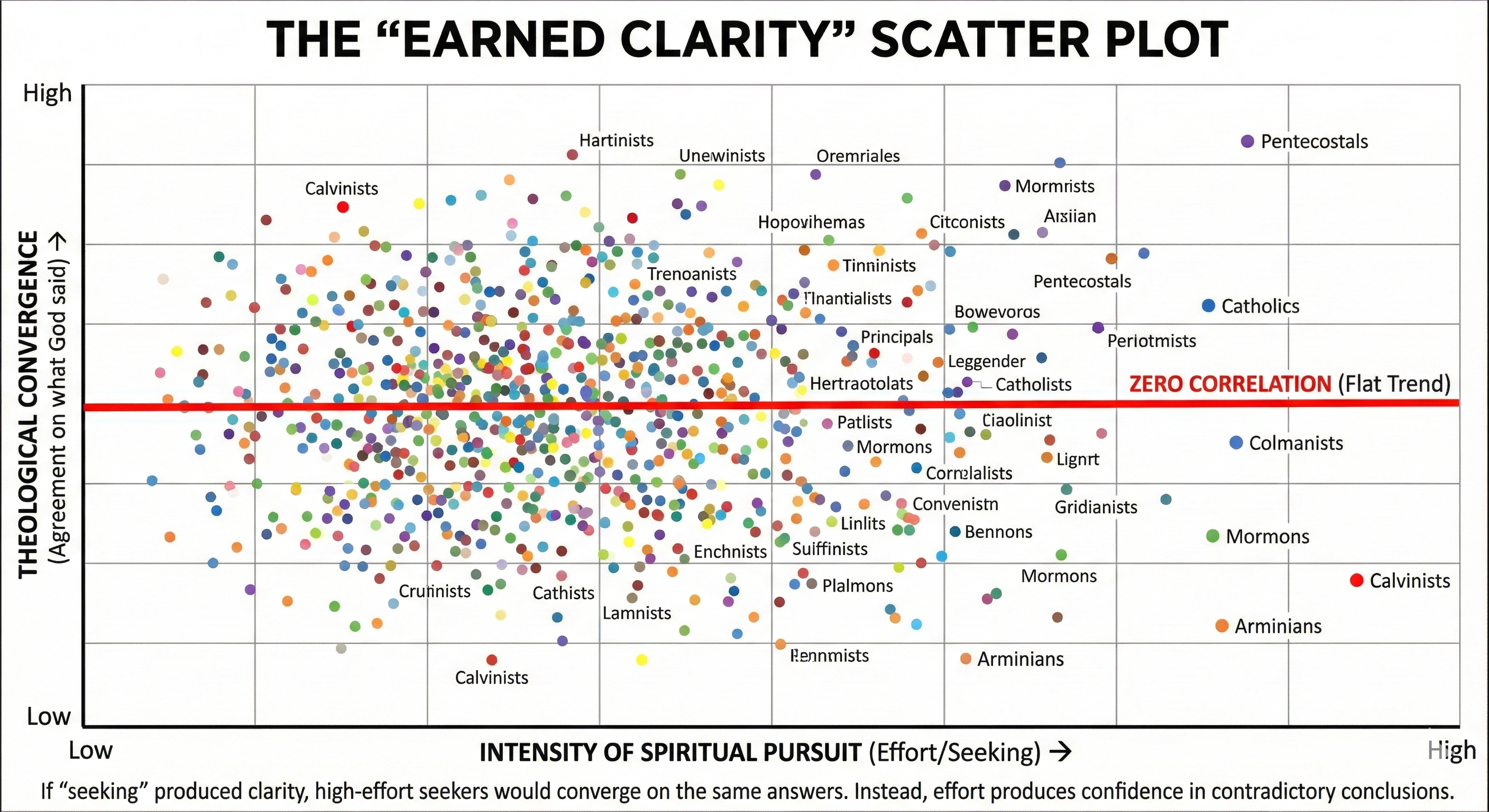

- There is Sufficient Evidence for the Christian God. Is this claim supported by global observations? Do people unexposed to Christianity experience encounters with the Christian God? The Christian God appears to initiate no personal relationship with those unfamiliar with him or even with those steeped in Christian culture. Christians often learn about God not through direct experience but through teachings and scripture. Can this truly be called a ‘personal’ relationship?

Historical Appearances vs. Modern Silence

A genuinely personal God would likely foster an unambiguous, two-way dialogue, eliminating any risk of miscommunication. Yet, the “personal” Christian God seems to use a book—a method of communication similar to countless other deities—without providing clarity. This method has led to numerous sects and interpretations, further obscuring his message. The Bible’s God appears reluctant to step forward.

In biblical accounts, God allegedly appeared directly to individuals, such as Saul on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:3). Historically, Christians have also claimed miraculous encounters with God. Interestingly, such reports have declined with the rise of scientific scrutiny. Has God’s approach “changed” in a way that makes him seemingly averse to evidence-based scrutiny?

The implications of divine hiddenness are profound. Even an indifferent deity might be expected to appear accidentally. Yet the Bible’s God seems to actively avoid human observation. This issue becomes more pressing when we consider the lack of responses to intercessory prayer and the persistence of human suffering. Does the absence of a visible, relational Christian God suggest that he is as unlikely to exist as any other unobservable deity?

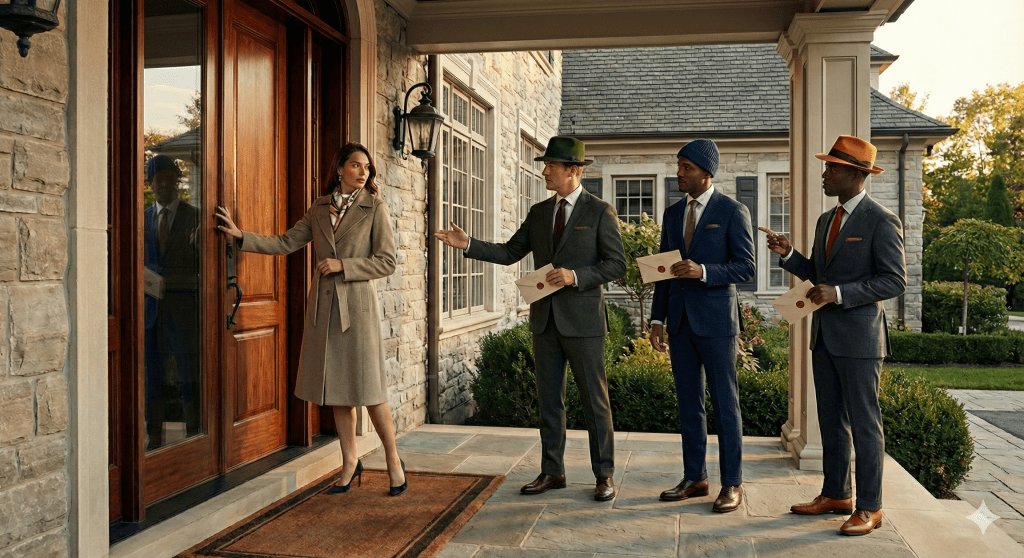

The Hidden Suitor: An Analogy for Divine Hiddenness

Consider Sally, a lonely woman who answers her door to find three men, each wearing a different colored hat. The green-hat man claims his friend Jim loves her deeply and is with her at that moment, urging her to sense his presence. The blue-hat man insists his friend Jack is always with her, needing only her belief. The orange-hat man asserts his friend Jake is standing behind her bedroom curtains, hoping for her belief. When Sally attempts to verify by pulling back the curtain, the men protest, suggesting she should feel his presence instead. They each offer her a love letter from their respective friends, urging her to believe without direct evidence.

(Jim, Jack, and Jake represent various alleged Gods.)

This scenario mirrors the concept of divine hiddenness, where multiple religions present sacred texts as evidence of their deity’s love and presence, yet none provide direct, unambiguous encounters. Believers are often encouraged to rely on faith and personal feelings rather than empirical evidence, leading to a multitude of conflicting beliefs, each supported by similar forms of indirect evidence.

The Power of Labeling Doubt as Wickedness in Religious Contexts

Religious communities often interpret doubt or disbelief in notions such as an omnipresent God authoring a “Holy Book” as a sign of moral failing or rebellion against the God in question. This approach serves several functions:

- Psychological Impact: It induces guilt and fear, discouraging individuals from questioning or seeking evidence.

- Social Impact: It fosters group cohesion by stigmatizing dissent, thereby maintaining uniformity of belief.

- Theological Impact: It reinforces authority and preserves doctrine by discouraging critical examination.

However, this tactic can suppress intellectual honesty, cause emotional harm, and alienate individuals who seek genuine understanding.

In conclusion, will we yield to the notion that any actual powerful God of the Universe desiring a relationship with each of us would have any cause to write a book to reveal himself? Is this not the anemic modus operandi of all religions each religion consider false? Would an actual God not make himself clearly known to honest and earnest seekers?

A Companion Technical Paper:

See also:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Divine Hiddenness and Personal Relationship

- Premise 1: If a personal God exists and desires a relationship with each individual, he would reveal himself in a clear, direct manner.

- Premise 2: The Christian God is said to desire a personal relationship with all individuals but relies on an indirect revelation through a book.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Christian God’s use of an indirect method (a book) instead of direct revelation calls into question the nature of his desire for a personal relationship.

Argument 2: Hiddenness and Free Will

- Premise 1: If free will is compromised by direct revelation, then a personal God would avoid direct interaction to preserve human freedom.

- Premise 2: Human freedom is not compromised by the presence of direct encounters; individuals can still accept or reject a suitor who reveals themselves directly.

- Conclusion: Therefore, direct revelation from a personal God would not violate free will, and the absence of such encounters raises questions about why he remains hidden.

Argument 3: Divine Hiddenness and Global Belief

- Premise 1: If sufficient evidence of the Christian God exists, people worldwide would naturally come to belief in him, regardless of cultural exposure.

- Premise 2: Many people without exposure to Christianity do not experience encounters with the Christian God, and even many Christians rely on scripture and teachings rather than personal experiences.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the lack of global belief in the Christian God suggests that sufficient evidence of his presence is lacking, undermining claims of his omnipresence and desire for relationship.

Argument 4: Comparison with Other Deities

- Premise 1: A unique and personal God would use a distinct and unequivocal method to reveal himself that separates him from other deities.

- Premise 2: The Christian God employs indirect revelation (through a book) that is highly equivocal, a method similar to that of other religions.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the use of scripture as a form of revelation makes the Christian God’s approach indistinguishable from that of other deities, questioning his uniqueness and personal nature.

Argument 5: Divine Silence and Evidence-Based Belief

- Premise 1: If a personal God previously appeared directly to individuals (as described in biblical accounts), then there is a precedent for direct encounters.

- Premise 2: Claims of direct encounters with God have significantly declined with the rise of scientific scrutiny.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the modern absence of direct encounters suggests that the Christian God may avoid evidence-based scrutiny, raising doubts about the reliability of past claims.

Argument 6: Doubt as Moral Failure

- Premise 1: If doubt and disbelief are morally condemned in religious contexts, this can discourage individuals from seeking evidence.

- Premise 2: Labeling doubt as a moral failure promotes group cohesion but can suppress intellectual honesty and emotional well-being.

- Conclusion: Therefore, labeling doubt as a moral failing discourages open inquiry and may alienate individuals seeking a genuine understanding, weakening the authenticity of faith.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Hidden God

CHRIS: As a Christian, I believe that God loves each of us deeply and desires a personal relationship with every individual. It’s why he gave us the Bible—to communicate his will and invite us to know him.

CLARUS: I understand the sentiment, Chris, but why would a personal God rely on a book to reveal himself? If he truly desires a relationship with each of us, shouldn’t he appear directly rather than using an indirect method that can be misinterpreted?

CHRIS: God uses indirect revelation to protect our free will. If he revealed himself in an undeniable way, we would have no real choice but to believe. He wants us to come to him freely, without feeling forced.

CLARUS: But that doesn’t quite follow, does it? Free will wouldn’t be undermined simply because God revealed himself clearly. We encounter other people directly and still have the choice to engage with them or not. Why would a direct encounter with God be any different?

CHRIS: I see your point, but God’s methods are mysterious. There is sufficient evidence in the world that points to God’s existence, and that should be enough for anyone who truly seeks him.

CLARUS: Let’s examine that claim. If there truly were sufficient evidence, we would expect people across all cultures and backgrounds to come to belief in the Christian God, regardless of their prior knowledge of Christianity. Yet, we see that people in non-Christian cultures don’t experience these kinds of personal encounters with God. Doesn’t that suggest a lack of sufficient evidence?

CHRIS: Well, I believe that God reaches people in different ways, often through their spiritual communities or personal faith journeys.

CLARUS: But if God’s primary method of revelation is indirect, how is that different from the methods claimed by other deities? Every religion has sacred texts and personal testimonies. Shouldn’t a unique and personal God employ a distinct method of revelation that sets him apart from these other deities?

CHRIS: God’s uniqueness is in his message of love and salvation, not necessarily in the way he reveals himself.

CLARUS: Yet, that’s exactly what causes confusion, Chris. By relying on the same indirect methods—scripture and feelings—the Christian God ends up looking indistinguishable from countless other gods. That seems at odds with the idea of a unique, all-powerful deity who desires a relationship with us.

CHRIS: Perhaps, but the Bible contains specific historical accounts where God did reveal himself directly. He appeared to Saul on the road to Damascus and spoke to prophets. Just because he doesn’t act this way now doesn’t mean he never did.

CLARUS: That’s an interesting point. Yet, isn’t it curious that these direct encounters seem to have faded precisely as scientific scrutiny has increased? It raises questions about whether these past encounters actually happened or if they were part of cultural beliefs that could not be tested.

CHRIS: You could say that, but maybe God’s interactions have changed to match the times. Faith should transcend evidence, shouldn’t it?

CLARUS: I’d argue that’s precisely the problem. When faith discourages evidence or even doubt, it risks suppressing intellectual honesty. When doubt is labeled as moral failing, people are discouraged from truly seeking truth. Doesn’t that undermine the authenticity of faith?

CHRIS: I wouldn’t call it suppression. Faith is about trust and accepting that we can’t always have all the answers. Not every doubt needs a response.

CLARUS: But encouraging open inquiry rather than discouraging doubt might actually strengthen faith. When faith communities label doubt as wickedness, it alienates those who seek genuine understanding. Isn’t that a dangerous path if truth is really the goal?

CHRIS: Perhaps there is some truth in that. Yet, for many, faith offers peace and community, even without concrete evidence. Isn’t that valuable?

CLARUS: It’s valuable to those who find it fulfilling, but it still leaves questions about divine hiddenness unanswered. If God wants a relationship with us, there’s still a contradiction in using hidden methods instead of direct encounters. The issue isn’t just the method but what it implies about the very nature of this relationship.

CHRIS: That’s a lot to consider. Maybe God’s ways are beyond human logic.

CLARUS: That could be true, but as rational beings, we’re bound to seek clarity where we can. If a personal God truly exists, I’d expect him to meet us halfway—not just with words on a page but with a presence that leaves no doubt.

This dialogue captures the contrasting perspectives on divine hiddenness, free will, evidence, and faith, rigorously addressing each point with an eye toward logical consistency and the implications of a personal God who remains hidden.

Click on the images below for a larger version.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Hidden Suitor

Imagine an unseen man named David who claims to love his partner, Sarah, yet never speaks to her directly. Instead, he leaves written messages around her home and asks her friends to knock on her door and convey his feelings. Sarah begins to wonder: If David truly cares and lives in my home, why doesn’t he reveal himself openly? In the same way, a personal God who wants a relationship but relies only on scripture and indirect methods may appear distant or indifferent, leading to questions about the authenticity of his desire for connection.

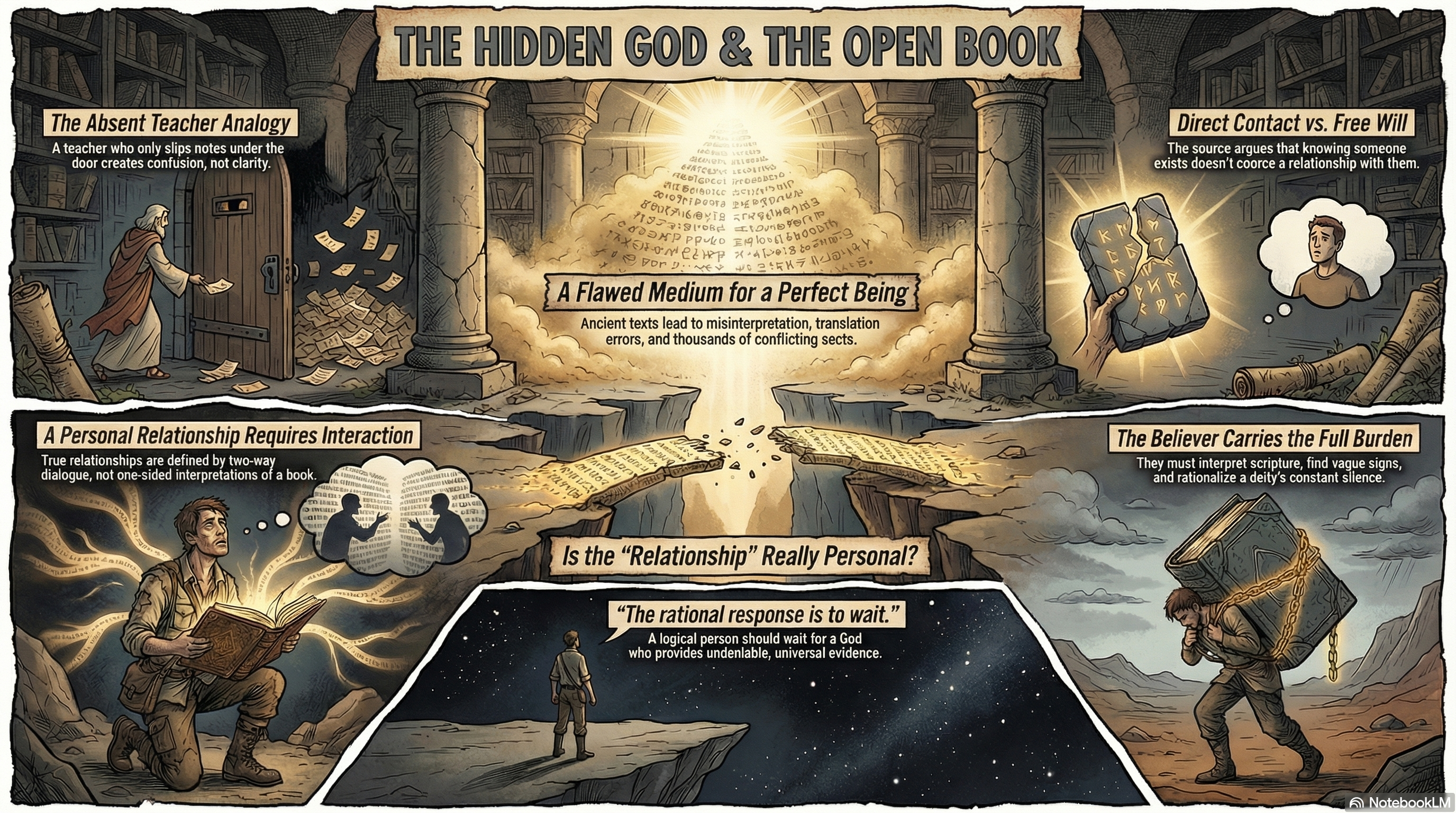

Analogy 2: The Absent Teacher

Consider a teacher who insists on being the best guide for his students but communicates solely through notes slipped under the classroom door, never appearing in person. The students, left to interpret his instructions on their own, often misinterpret his teachings and argue over his intentions. Similarly, a God who chooses a book as his primary communication method rather than direct interaction can leave believers struggling with different interpretations, suggesting that such a method may not be suited to an all-knowing deity who wants to ensure understanding.

Analogy 3: The Silent Friend

Imagine a friend you have never met in person who claims to be standing invisibly behind you at every moment, ready to support you, but never speaks or appears when you need him. He only leaves messages that you find days later, and even then, they are often vague and hard to interpret. Like this friend, a God who is supposedly omnipresent but remains hidden despite professing care leaves those seeking him feeling uncertain, raising doubts about his intentions and commitment to a genuine relationship.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Divine Hiddenness and Human Freedom

Theologians might argue that God’s hiddenness is necessary to preserve human free will. If God were to reveal himself in an undeniable manner, it could compel belief and devotion, effectively coercing individuals into a relationship. By allowing room for doubt, God provides humans with genuine freedom to seek, question, and decide whether to pursue a relationship, making faith an authentic, voluntary response.

2. The Sufficiency of Evidence through Creation and Conscience

Many theologians claim that God’s existence is already apparent through the natural world and the inner workings of human conscience. From this perspective, creation itself acts as a form of general revelation that points to a divine origin, offering sufficient evidence for those who seek him. This view suggests that scripture and personal faith experiences supplement, rather than replace, the broader signs of God’s presence.

3. God’s Use of Scripture as a Universal and Timeless Medium

A common theological perspective is that scripture serves as a universal and timeless medium through which God communicates with all of humanity across generations. Unlike direct appearances limited to a single time and place, scripture provides a consistent, lasting record of God’s will and character. The written word, therefore, allows people from diverse backgrounds to encounter God’s message, irrespective of when or where they live.

4. Scripture as a Catalyst for Faith and Community

Theologians may argue that scripture fosters faith not by eliminating doubt but by encouraging individuals to seek and explore. The Bible invites believers into a community of faith where people can interpret, question, and support each other. This communal approach enables individuals to develop a deeper, relational understanding of God, making faith a journey rather than an immediate certainty.

5. Mystery as a Component of Divine Relationship

Some theologians view divine mystery as essential to a meaningful relationship with God. If God were fully understandable or visible, the relationship might lose depth and reverence, as human minds could never completely grasp an infinite and transcendent being. By maintaining an element of mystery, God encourages believers to approach him with humility, awe, and a recognition of their own limitations.

6. The Role of Personal Revelation in Faith

Theologians might emphasize that God often reveals himself personally through prayer, meditation, and personal experiences rather than through universal encounters. These individual revelations are seen as a core part of faith, designed to meet each person’s unique needs and circumstances. Direct encounters are not absent but may be subtle, accessible to those who cultivate a spiritual openness to God’s presence in their lives.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to Divine Hiddenness and Human Freedom

The assumption that direct revelation would undermine human free will seems questionable. Freedom of choice is not compromised simply by acknowledging the existence of another being; people encounter others daily without losing their autonomy to engage or ignore them. A loving God who desires genuine relationship could still reveal himself plainly, allowing individuals the freedom to choose whether or not to embrace his guidance without having to wonder about his existence in the first place.

2. Response to the Sufficiency of Evidence through Creation and Conscience

While nature may evoke a sense of wonder, it does not unequivocally point to a personal deity with specific intentions and characteristics, let alone the Christian God. Additionally, conscience and moral sense are seen in many cultures and religions, yet they lead to vastly different beliefs about the divine. If God intends to be known specifically as the God of Christianity, relying on general evidence like nature and conscience seems inadequate and indistinguishable from what one might observe in belief systems without a personal, relational God.

(* But this does appear testable.)

3. Response to God’s Use of Scripture as a Universal and Timeless Medium

A book as a medium for universal communication is inherently flawed, as it is subject to cultural, linguistic, and historical interpretation. Over time, scriptures can be misinterpreted, mistranslated, and even altered, leading to sectarian divisions and conflicting doctrines. If God intended to make himself universally known, direct, personal encounters would ensure clarity and prevent the misunderstandings that have led to countless doctrinal disagreements.

4. Response to Scripture as a Catalyst for Faith and Community

While scripture may foster faith and community, it also often encourages conformity over inquiry, discouraging open doubt. The communal reinforcement of scriptural beliefs can lead individuals to accept doctrines without questioning them or seeking evidence. A personal God who values genuine understanding would presumably support a form of communication that facilitates direct knowledge rather than one that often leads to division and indoctrination.

5. Response to Mystery as a Component of Divine Relationship

The appeal to mystery as a basis for faith undermines the goal of any personal relationship, which inherently involves mutual understanding. A relationship rooted in ambiguity and hiddenness resembles a one-sided connection where one party is left to speculate, rather than know, the other’s nature. If God desires a relationship of love and understanding, the reliance on mystery over clarity makes the connection seem distant and even manipulative, as it forces individuals to rely on blind faith rather than informed trust.

6. Response to the Role of Personal Revelation in Faith

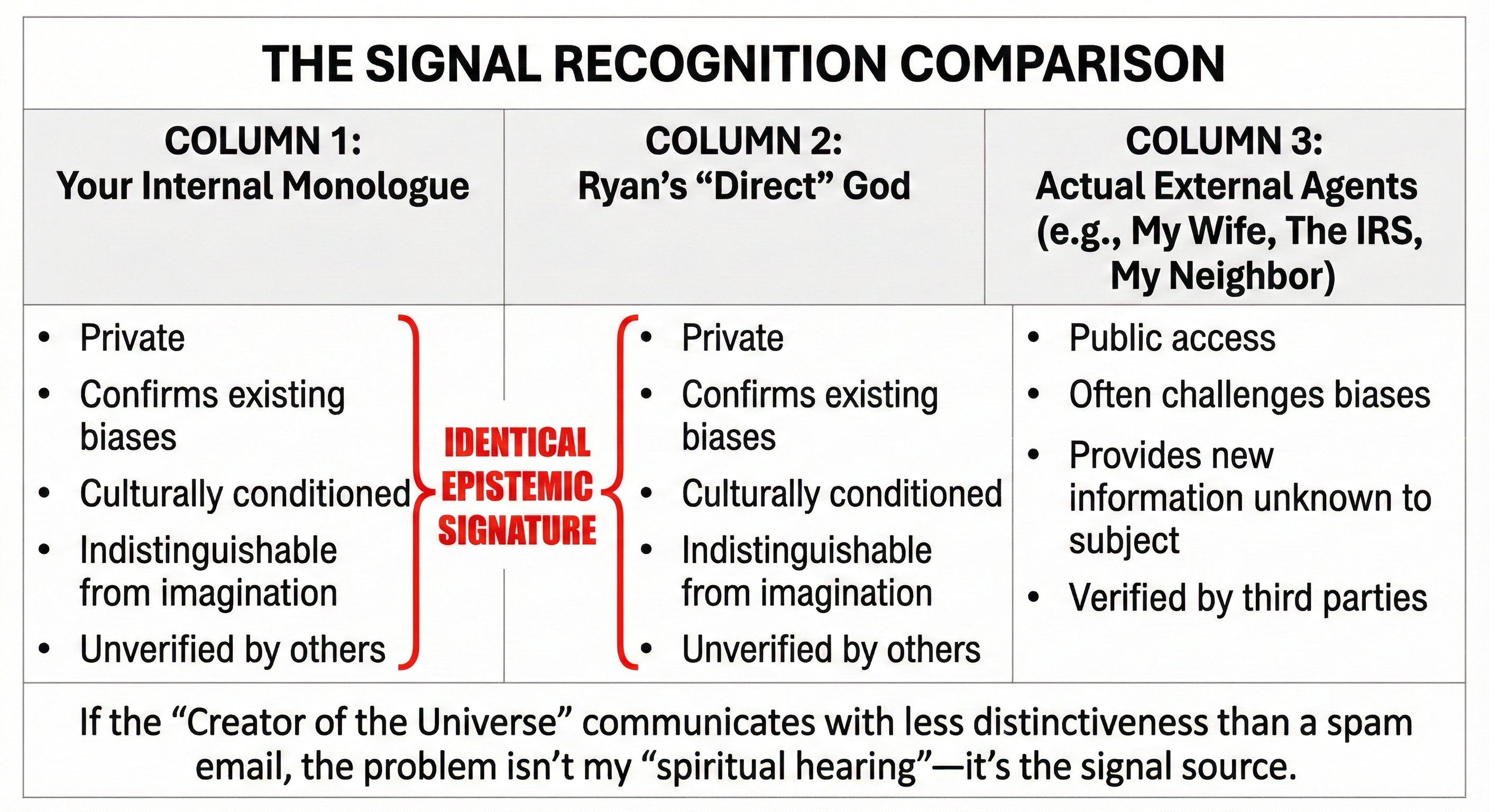

Personal revelation may feel meaningful to individuals, but it is by nature subjective and highly variable, leading to inconsistencies and conflicting beliefs even among those who follow the same religion. This subjectivity makes it difficult to distinguish genuine divine encounters from personal psychological experiences or cultural conditioning. A God who intends to establish universal truths would not rely on private, unverifiable experiences but would instead engage in consistent, clear, and direct communication accessible to all people, regardless of their personal beliefs or mental state.

Clarifications

Divine Hiddenness

Divine hiddenness refers to the theological and philosophical issue of why a loving and personal God remains unseen or seemingly distant. If such a God desires a relationship with humanity, his apparent hiddenness or lack of direct engagement raises questions about his intentions or even existence. This problem is central to arguments questioning the nature of divine interaction with humanity.

Free Will and Coercion

In theological arguments, free will is often cited as the reason God doesn’t reveal himself more directly. The claim is that if God’s presence were undeniable, it would coerce belief, undermining an individual’s ability to freely choose to follow him. However, free will in this context means the freedom to accept or reject a relationship or belief, which is technically different from simply acknowledging someone’s existence.

General Revelation vs. Special Revelation

General revelation refers to knowledge about God inferred from nature, conscience, or creation, accessible to all people. Special revelation, on the other hand, involves specific communications from God, such as the Bible or personal experiences claimed by believers. Theological arguments often suggest that general revelation should be enough to lead people to believe, but critics argue that this evidence is ambiguous and insufficient to establish belief in a specific, personal deity.

Scripture as a Medium

Scripture, in religious terms, is viewed as a written, authoritative document intended to convey divine teachings and guidance. However, the use of scripture as a universal communication tool has limitations. Variations in translations, interpretations, and cultural contexts mean that messages in religious texts are often understood differently, leading to doctrinal splits and a wide array of sectarian beliefs.

Mystery in Theology

In theological contexts, mystery refers to aspects of God or divine will that are thought to be beyond human comprehension. Some theologians argue that mystery invites believers to approach God with humility and faith. Critics, however, contend that too much reliance on mystery can obscure accountability and prevent open inquiry, as it shifts the burden away from seeking clarity and toward accepting uncertainty.

Personal Revelation and Subjectivity

Personal revelation involves experiences or insights individuals believe to be directly from God, often perceived through prayer, meditation, or personal intuition. While these experiences are deeply meaningful to those who have them, they lack objective verification and can differ significantly between individuals, even within the same religion. The subjectivity of personal revelation often makes it difficult to distinguish between genuine divine encounters and personal or psychological experiences.

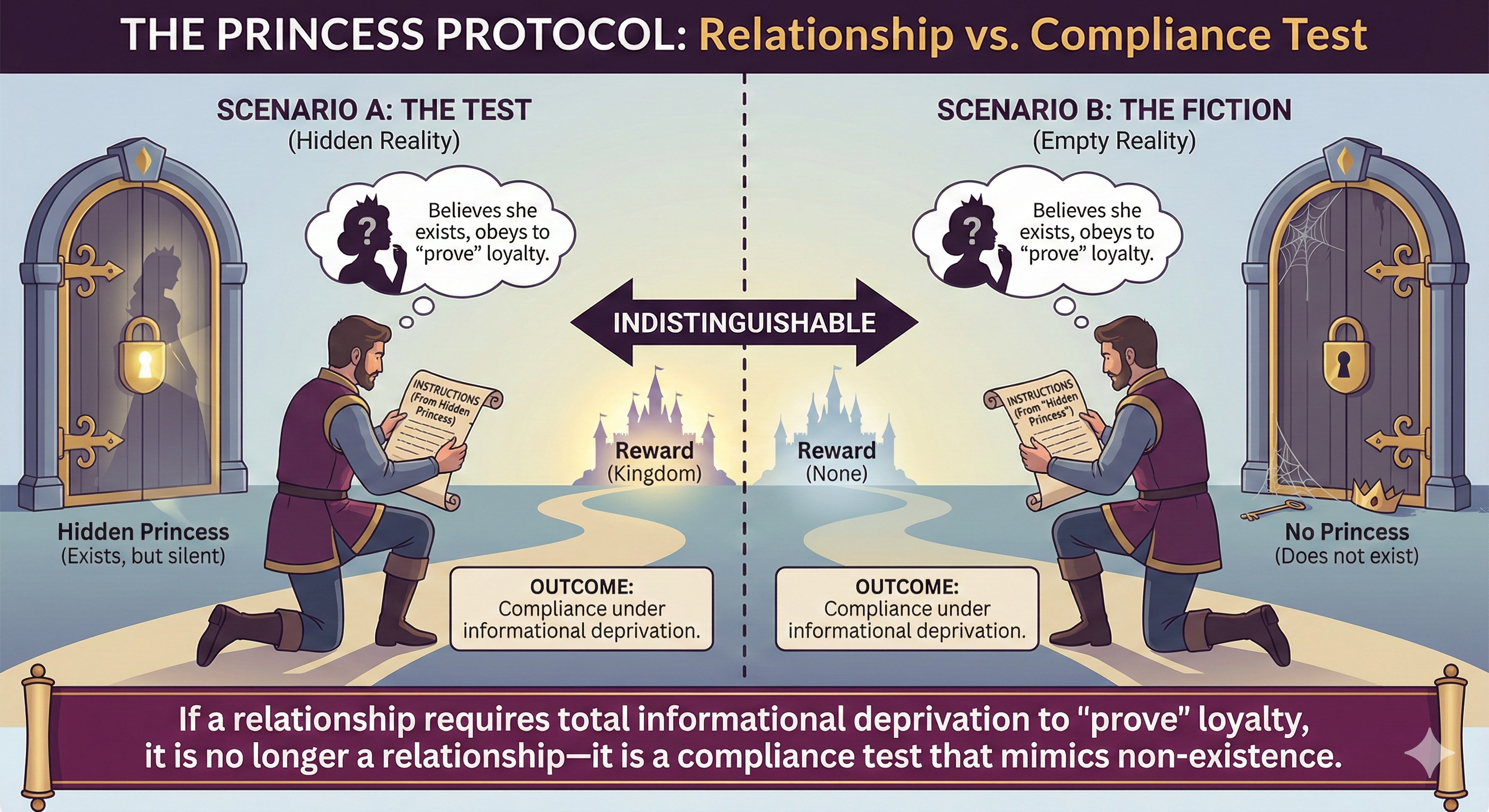

Calling a Relationship with a Hidden God “Personal”

The notion of a personal relationship with a God who remains entirely hidden and communicates only through an ancient book or subjective life experiences deserves rigorous scrutiny. When relationships are defined by mutuality, direct interaction, and shared understanding, labeling such an elusive and indirect connection as “personal” strains the very concept of what a relationship entails. Below, I explore why this characterization is both logically inconsistent and, in many respects, absurd.

1. Lack of Direct Interaction

A defining feature of any personal relationship is direct interaction—the ability to communicate openly and clearly with the other party. In human terms, relationships are strengthened through shared dialogue, gestures, and mutual understanding. By contrast, the Christian God, as described, never engages directly with believers. Instead, communication is purportedly channeled through the Bible, a collection of writings thousands of years old, and through subjective interpretations of life events. This reliance on indirect methods deprives believers of the opportunity to verify, clarify, or respond to the supposed communication, making the “relationship” unidirectional and inherently ambiguous.

2. Overreliance on a Book

The claim that the Bible serves as the cornerstone of a “personal relationship” with God is problematic for several reasons:

- Cultural and Temporal Distance: The Bible was written in ancient contexts that are far removed from the realities of modern life. Readers must navigate historical interpretations, linguistic variations, and theological disputes to even approximate its intended message.

- Conflicting Interpretations: The Bible has led to the creation of thousands of sects, each claiming different understandings of its meaning. This diversity raises questions about whether the text can serve as a coherent or reliable basis for a “personal” connection with an omnipotent deity.

If God desired to establish an unequivocally personal relationship, relying on such an imprecise and divisive medium seems profoundly ill-suited to the task.

3. Subjectivity of Life Events

Believers often cite personal life events as evidence of God’s involvement, interpreting moments of fortune, resolution, or comfort as signs of divine presence. However, this interpretation is inherently subjective and indistinguishable from cognitive biases or psychological tendencies to attribute meaning to randomness. If a “personal” God exists and acts in human lives, these acts should be unambiguous and consistent across cultures and individuals. Instead, the vagueness of such attributions often mirrors similar claims made by adherents of other religions, making them indistinguishable from generalized human experiences rather than evidence of a specific deity’s involvement.

4. Absence of Mutuality

In human relationships, mutuality—the ability for both parties to interact and respond—is key. A personal God, as claimed, neither responds directly nor clarifies his intentions in any verifiable way. Prayer, often described as communication with God, results in no tangible dialogue; believers are left interpreting silence or subjective feelings as divine responses. This absence of mutual exchange reduces the relationship to an exercise in one-sided projection, where the believer assumes God’s presence without receiving any concrete confirmation.

5. Incoherence in Calling Hiddenness “Personal”

The term “personal” implies proximity, accessibility, and intimacy—qualities that directly conflict with divine hiddenness. A God who remains hidden, avoiding direct encounters and failing to offer unmistakable evidence of his presence, cannot logically be described as engaging in a personal relationship. If God’s hiddenness is intentional, as some theologians argue, then it seems to undermine the very idea of a personal connection, making the term both misleading and inconsistent.

6. The Burden on the Believer

In any relationship, the effort to maintain connection should be shared. With the Christian God, however, the burden of belief rests entirely on the believer. They are expected to interpret scriptures, discern God’s presence in vague signs, and accept hiddenness as part of his nature. This dynamic places the entirety of relational effort on one side, leaving believers to do the work of imagining, seeking, and rationalizing God’s role in their lives. Such a lopsided arrangement does not resemble any personal relationship as we understand the term.

7. Parallels to Fictional and Nonexistent Entities

The type of “relationship” described bears striking similarities to the connections people form with fictional characters or abstract ideals. For example, readers of novels or viewers of films often feel emotional connections to characters despite knowing they are not real. The absence of a verifiable response from God makes the connection believers claim indistinguishable from such experiences, further casting doubt on its personal nature.

8. The Problem of Exclusivity

If this God desires a personal relationship with everyone, why is his “voice” so limited to those exposed to certain cultures and religious teachings? Billions of people live and die without hearing of the Christian God, much less experiencing a “relationship” with him. This exclusivity contradicts the idea of a universal, personal God and suggests that the relationship is either inaccessible to many or entirely mischaracterized.

Conclusion

A “relationship” with a God who never interacts directly, relies on an ambiguous and divisive book, and remains hidden behind subjective experiences cannot reasonably be described as personal. The lack of direct interaction, mutuality, and clarity makes the term absurd in this context. If believers wish to claim a personal connection with God, they must reconcile the inherent contradictions in the nature of divine hiddenness and the reliance on indirect methods that resemble those used by fictional or imagined entities. Without such reconciliation, the concept remains logically untenable and fundamentally flawed.

The Tension in Christian Miracle Claims:

Miracles for Revelation vs. Miracles and Human Unbelief

There is a deep and often unexamined tension at the heart of Christian claims about miracles and divine revelation. On one hand, believers assert that miracles are performed by God to make Himself known to humanity—to authenticate messengers, inspire faith, and provide unmistakable signs of His presence and character. On the other hand, when critics question why miracles are not universally observable or reproducible today, apologists commonly argue that miracles would not necessarily produce belief, pointing to biblical examples where witnesses remained skeptical or rebellious despite extraordinary events.

◉ The Stated Purpose of Miracles

Scripture presents miracles as unmistakable interventions—parting seas, raising the dead, healings, and supernatural signs. The supposed function of these acts is to confirm God’s reality, establish authority, and create faith. If this were not their purpose, their public and spectacular nature would seem pointless. Both Old and New Testaments depict miracles as means by which God “proves” Himself, with onlookers either responding with awe and faith or being held especially culpable for disbelief in light of such clear evidence.

◉ The Modern Shift: Miracles and Unbelief

Yet when contemporary skeptics ask why God does not perform obvious miracles today, the response often pivots: “Even in biblical times, people did not always believe despite miracles.” This introduces an equivocation—if miracles fail to produce belief, why does God perform them at all, and why does their absence now excuse disbelief? The argument undermines itself: either miracles are effective signs, or they are not. If they are not, then their apologetic value evaporates. If they are, then the lack of such signs today is conspicuous and problematic for the claim that God wants to be known.

◉ Logical Tension and Its Consequences

This tension can be formalized as follows:

— P1: If God wants to be known, He would provide clear, public evidence (miracles).

— P2: The Bible claims God did so in the past, and those miracles led many to faith.

— P3: But the same Bible and apologists say that many still rejected God even after seeing miracles.

— P4: Therefore, God is justified in not providing public miracles now, since some will disbelieve anyway.

But this line of reasoning fails: the fact that some disbelieve does not negate the profound effect such events would have on sincere seekers, nor does it explain why public, verifiable miracles are now absent, replaced by private anecdotes, third-hand stories, and ambiguous experiences. If the function of miracles is to make God known, their current nonexistence under scrutiny calls into question either God’s desire to be known, His ability to perform them, or the veracity of the original miracle claims themselves.

◉ Conclusion

To claim that God performed miracles to reveal Himself and then withdraws that method because belief was not universal is to set up a contradiction. Miracles cannot be both the primary means of divine revelation and irrelevant to belief. The failure to resolve this tension leaves the doctrine of miracles logically unstable and epistemically unsatisfying for anyone seeking coherent reasons to believe.

Attempted Refutation (Raul #1)

Raul Matsuda Renteria

1. God Is Not Entirely Hidden—But Neither Is He Overwhelmingly Obvious

Scripture affirms both the clarity of God’s revelation and the mystery of His ways:

• “The heavens declare the glory of God…” (Psalm 19:1)

• “…what may be known about God is plain…because God has made it plain… so that people are without excuse.” (Romans 1:19–20)

Creation, conscience, history, and the person of Jesus are presented as real ways God has revealed Himself. But Scripture also says:

• “Truly you are a God who hides himself…” (Isaiah 45:15)

• “We walk by faith, not by sight.” (2 Corinthians 5:7)

This tension suggests God’s presence is available but not unavoidable. He reveals enough for genuine seekers to respond, yet not so much that faith becomes coercion. This is not about playing hide and seek—it’s about love seeking relationship, not robotic compliance.

2. The Cry for God’s Presence Is Found Within the Bible

Scripture doesn’t shy away from this very complaint:

• “How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?” (Psalm 13:1)

• “Why, Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?” (Psalm 10:1)

• Even Jesus cries, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46)

These aren’t signs of disbelief, but the honest wrestling of the faithful. The Bible doesn’t depict perfect knowledge as the prerequisite for relationship with God—but rather humility, trust, and endurance in the face of ambiguity.

3. Why Was God So Visible in the Bible?

It’s important to remember: the Bible condenses centuries of history into a few pages. God’s vivid appearances (theophanies) are rare, even in Scripture. And even those who witnessed miracles often still doubted or disobeyed (e.g., Israel in the wilderness, Judas, the Pharisees).

Jesus acknowledged this paradox when He said:

• “If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.” (Luke 16:31)

In biblical terms, more evidence doesn’t always equal more faith.

4. Is Divine Hiddenness Proof of Absence—or an Invitation to Deeper Seeking?

Jeremiah 29:13 says, “You will seek me and find me when you seek me with all your heart.” The key phrase is “with all your heart.” Scripture insists that true seeking is not merely intellectual pursuit, but relational surrender. The issue isn’t sincerity alone—it’s openness to the kind of God who is, not the kind we prefer.

This is not to invalidate the pain of silence—but to reframe it: God’s apparent absence might sometimes be a way of deepening our longing, our trust, or even stripping away false idols.

5. Faith, Not as Blindness, but Relational Trust

Biblical faith is not belief without evidence; it’s trust based on testimony, experience, and the character of God revealed over time. The call is not to blind assent but to personal relationship—faith in a Person, not just an idea.

In Closing:

From a biblical perspective, divine hiddenness doesn’t point to neglect, but to a God who reveals enough to invite, but not enough to compel. It leaves room for love to be chosen freely.

This doesn’t remove all tension, but maybe that’s the point. Faith, in the biblical sense, lives in the space between silence and presence, between longing and trust. Will you trust?

Phil Stilwell’s Counter-Response:

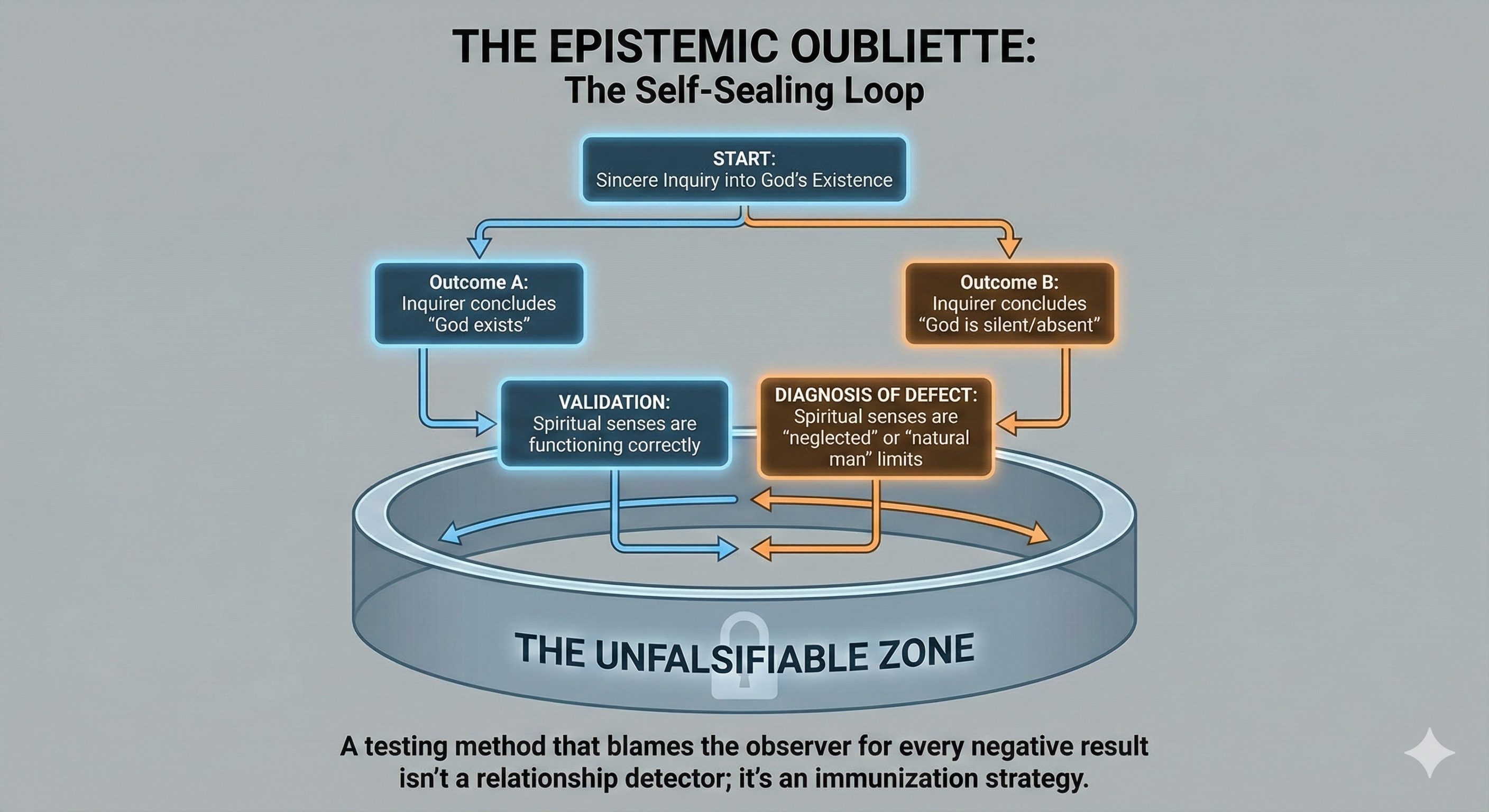

Below you’ll find syllogistic breakdowns to show where your argument either fails logically or rests on circular, untestable claims.

1. “God Is Not Entirely Hidden—But Neither Is He Overwhelmingly Obvious”

You assert that God reveals just enough for sincere seekers, but not enough to coerce belief.

Syllogism A

— P1: God reveals Himself through creation, conscience, Jesus, and history.

— P2: These revelations are sufficient for genuine seekers.

— C: Therefore, God’s revelation is sufficient but non-coercive.

Problem: This collapses into circular reasoning:

Syllogism A′ (Unstated but Implied)

— P1: Genuine seekers find God.

— P2: If someone doesn’t find God, they weren’t a genuine seeker.

— C: Therefore, everyone who sincerely seeks finds God.

This defines sincerity by whether the person ends up believing, making the system unfalsifiable and immune to counterexamples.

1. God Is Partially Hidden to Prevent Coercion

Claim: God reveals just enough to sincere seekers but not enough to overwhelm or coerce.

Formal Logic

Let:: x is a genuine seeker

: x finds God

: Revelation is sufficient

: Revelation coerces belief

Your argument structure implies:

Flaw: Tautology

This reduces to:

Which means sincerity is defined by the outcome (finding God), making the claim logically unfalsifiable.

2. “The Cry for God’s Presence Is Found Within the Bible”

You argue that even biblical believers struggled with divine silence.

Syllogism B

— P1: Biblical believers cry out in times of perceived divine absence.

— P2: These cries reflect ongoing faith despite ambiguity.

— C: Therefore, divine hiddenness is consistent with faithful relationship.

Problem: This only documents the problem—it doesn’t solve it. Quoting lamentations doesn’t prove the God they lamented to was present; it shows that even the faithful felt abandoned. That’s not evidence of presence—it’s evidence of theological rationalization in response to divine silence.

2. Biblical Laments Indicate God’s Hidden Yet Present Nature

Claim: Lamenting God’s silence still occurs within genuine relationship.

Let:: x laments divine hiddenness

: x is in relationship with God

: God is present

: God is hidden

You suggest:

Flaw: Affirming the Consequent

Even if is observed, it does not logically imply

or

. Silence is consistent with both presence and absence. The argument commits:

, therefore

, therefore

,

which is a logical fallacy.

3. “Why Was God So Visible in the Bible?”

You claim theophanies were rare even in scripture, and that miracles didn’t guarantee faith.

Syllogism C

— P1: The Bible condenses centuries of history where divine appearances were rare.

— P2: Even those who saw miracles often still doubted.

— C: Therefore, more visible evidence would not lead to more belief.

Problem: This is a non sequitur.

— Just because some people doubted miracles doesn’t mean clearer evidence isn’t helpful.

— Just because theophanies are rare in scripture doesn’t mean they were rare in reality—it may just reflect selective narrative compression.

Moreover, if God’s desire is universal relationship, why restrict clarity to a few people in one region and era while demanding faith from the rest based on secondhand reports?

3. Rare Theophanies Explain Today’s Hiddenness

Claim: God’s appearances were rare even in the Bible, and many still doubted despite witnessing them.

Let:: Theophany

: x believes

: x disbelieves

: Miracle occurs

Your argument implies:

occurred

Therefore:

Flaw: Hasty Generalization

Inferring from a few recorded instances that miracles do not lead to belief is logically invalid. The move from:

to

is unwarranted.

4. “Is Divine Hiddenness Proof of Absence—or an Invitation to Deeper Seeking?”

You say that hiddenness can refine the seeker, exposing idols and deepening trust.

Syllogism D

— P1: God’s hiddenness can deepen longing, trust, and relational humility.

— P2: This kind of formative silence may be beneficial to the seeker.

— C: Therefore, divine hiddenness serves a relational and sanctifying purpose.

Problem: This is an ad hoc explanation. You’re assigning meaningful intent to silence that is equally consistent with absence. Just as a silent partner in a relationship might not exist, so too might a silent God. You’re interpreting absence as formative because you already believe the person is there. That’s psychological projection, not argument.

4. Hiddenness as Spiritual Formation

Claim: God’s hiddenness produces spiritual benefits like trust and detachment from idols.

Let:: God hides

: Faith deepens

: Idols are stripped

: God exists

Your argument implies:

Flaw: Non Sequitur

From or

, it does not follow that

is true. The conclusion:

is logically invalid. Growth during silence does not prove the presence of a being—only the human capacity for meaning-making.

5. “Faith, Not as Blindness, but Relational Trust”

You claim faith is not blind but trust grounded in God’s revealed character over time.

Syllogism E

— P1: Faith is relational trust in a person, not blind belief in a concept.

— P2: God has revealed His character through scripture, conscience, and experience.

— C: Therefore, faith is justified as a relational response to God’s self-disclosure.

Problem: This presumes what needs to be proven. It’s epistemically circular: you trust God’s character because it’s revealed in sources you already deem reliable—but those sources are the very thing being questioned. If you began from neutral ground, would you find their content sufficient to conclude divine authorship? Cultural and doctrinal variation suggests otherwise.

5. Faith as Trust Based on Testimony

Claim: Faith is relational trust grounded in experience and scripture.

Let:: Testimony

: Character of God

: Faith

: Revelation is reliable

Your argument implies:

Flaw: Epistemic Circularity

This assumes the reliability of the very sources under question. The structure is:

There is no external validation. It becomes:

Which loops without grounding.

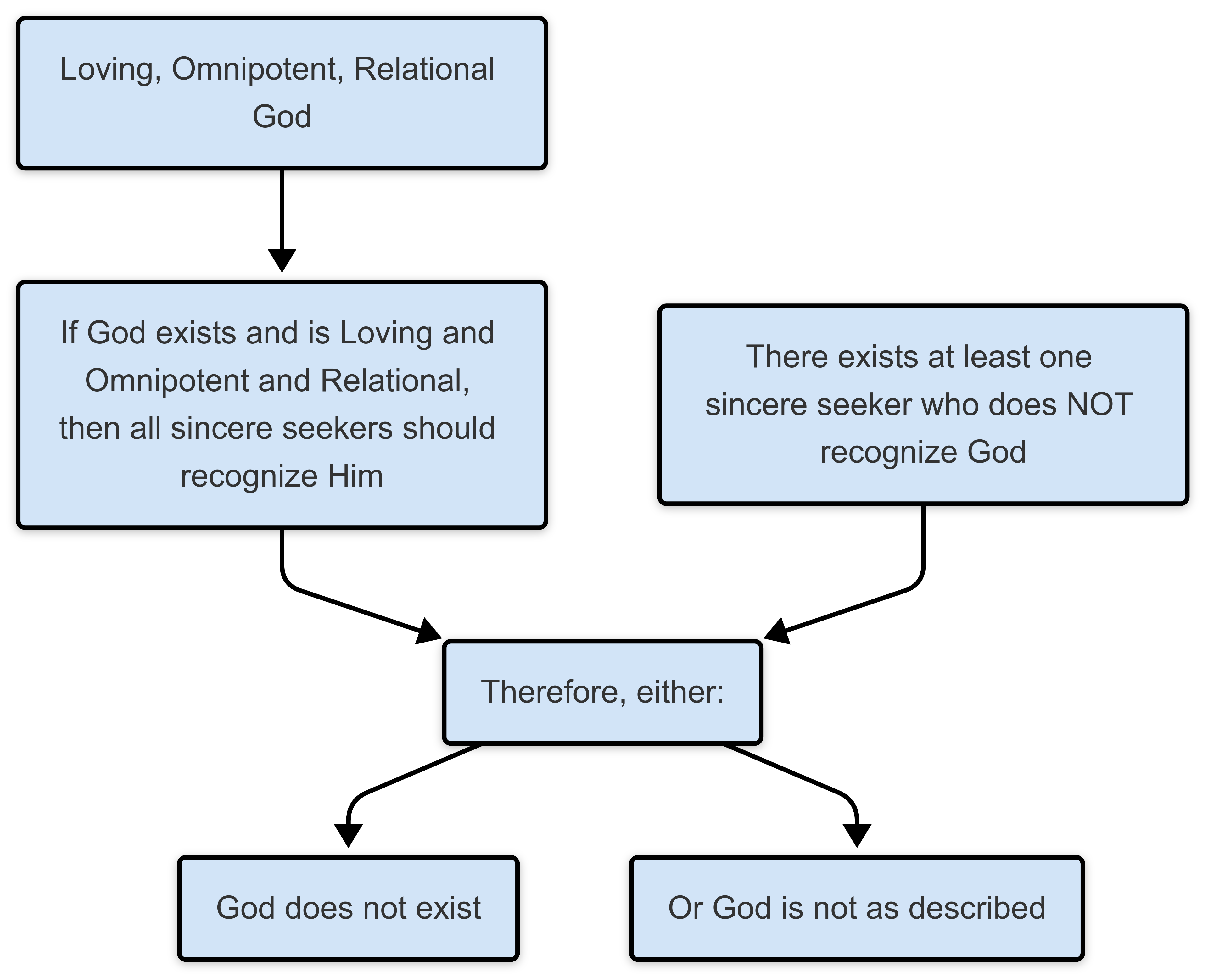

Conclusion: Divine Hiddenness is Incompatible with the Claim of a Relational God

Syllogism F

— P1: A personal, loving God who desires relationship would make Himself clearly knowable to all sincere seekers.

— P2: Countless sincere seekers—across cultures, histories, and religions—fail to perceive this God despite effort.

— P3: The responses to this failure are circular (“they weren’t sincere”) or ad hoc (“God is shaping them”).

— C: Therefore, it is more plausible that either this God does not exist or does not desire universal relationship.

Final Deductive Refutation of Raul’s Model

Let:: God exists and desires relationship

: Revelation is sufficient

: x sincerely seeks

: x finds God

: x experiences divine silence

: Belief in God

If:

and we observe:

Then:

Raul defaults to:

(always the fault of the seeker)

But this is unfalsifiable and circular, confirming whatever the theology demands, not what the evidence reveals.

You speak often of love, trust, and mystery, Raul—but these cannot replace clarity where clarity is required. Faith in a hidden God is not relational—it is speculative. If there were a loving God eager for connection, we would not be debating His existence at all.

Attempted Refutation (Raul #2)

Raul Matsuda Renteria

✳️ Response to Point 1: Absence Is Not Nonexistence

You rightly distinguish between deductive and abductive reasoning, and I appreciate your probabilistic rather than absolutist stance. However, your analogy between human relationships and a divine one assumes parity between finite beings and an infinite, ontologically distinct God. Unlike a spouse or friend, God—if He exists—is not our peer and does not operate under the same social expectations.

Still, Christianity maintains that God desires relationship and is not arbitrarily silent. The phenomenon of divine hiddenness may serve multiple purposes: soul-making, preserving moral freedom, or deepening faith through seeking. Divine presence might not always be overt—but is not wholly absent either. Across cultures and eras, many have reported transformative encounters that they attribute to God. These experiences, while often subjective, are no less meaningful to those who report them.

What some call “absence” may simply reflect an expectation of how God should communicate—not evidence that He does not.

✳️ Response to Point 2: Clarity vs. Coercion

Your challenge to the coercion argument is sharp, but I think it misses the nuance. The recognition of God’s authority involves more than acknowledging His existence. If God’s reality were as obvious as gravity, then submission might become coercion—driven by fear or obligation rather than genuine trust.

Even in the Gospels, Jesus often revealed Himself selectively. The aim appears to be voluntary engagement, not overwhelming proof. Yes, divine ambiguity seems uneven, but Christianity interprets this as divine accommodation—God meets individuals in ways suited to their context, whether through nature, conscience, Scripture, or relationships. Uneven persuasion does not equal randomness—it may signal intentional, relational variance.

✳️ Response to Point 3: Doubt vs. Projection

Your caution against emotional rationalization is valid—but keep in mind that projection can go both ways. Believers and skeptics alike are vulnerable to interpreting the world through emotional lenses. You let go of belief after rational inquiry, which deserves respect. But from a Christian standpoint, a relational God might intentionally allow intellectual struggle because faith involves trusting amid uncertainty.

Skepticism isn’t always brave, and belief isn’t always blind. The challenge is to embody epistemic virtue—following the evidence even when it leads away from comfort. Christians too must be willing to revise their views if God differs from theological expectations. The real question remains: What does the full scope of evidence, history, and experience point to as most plausible?

✳️ Response to Point 4: Jesus and the Hidden God

You argue that Jesus shifts the hiddenness problem without resolving it—but I’d challenge that. Christianity presents Jesus not as a mere historical figure, but as a continuing presence through the Holy Spirit. The disparity in experiences is unsettling—but consider: not everyone experiences beauty, grief, or even love identically. Subjective variation doesn’t eliminate the possibility of objective presence.

Yes, the New Testament is testimonial, but testimony is a legitimate form of evidence—in both history and courtrooms. It should be scrutinized, but not dismissed outright, especially when it’s coherent, well-sourced, and transformative.

The deeper question is: What kind of God chooses testimony over domination? The Christian answer: a God who values vulnerability, invitation, and relational pursuit over raw imposition.

✳️ Response to Point 5: “God on Your Terms”

Your final syllogism is compelling, but hinges on a key assumption: that if God desires relationship, He must remove all doubt for every sincere seeker. But what if God seeks not just intellectual assent, but spiritual transformation? That requires a context where the will remains free, the heart open, and the pursuit authentic.

God’s “absence” on our terms may reflect not negligence, but irreducibility to human expectations. That’s not a dodge—it’s an invitation. Christianity offers a door that is open—but one that leads into relationship, not an experiment.

✅ Final Reflection

You argue that ambiguity is rebranded silence. I see it as an invitation—not to abandon rationality, but to expand it. The God of Scripture promises not spectacle on demand, but: “Seek and you shall find.”

Seeking, in this view, isn’t merely analytical—it’s existential, moral, and emotional. This doesn’t negate rationality; it completes it. If God is love, then knowing Him wouldn’t just involve epistemic rigor—it would demand relational vulnerability.

So I ask again: When will you believe?

Phil Stilwell’s Counter-Response:

Raul, I appreciate the layered reply. You’ve tried to bring depth and nuance, but what we now have is a bundle of smuggled assumptions, category shifts, and sophisticated circularity dressed in the language of philosophical openness. Let’s not confuse complexity for clarity. I’ll walk through your responses by first laying out the strawman syllogisms you appear to rely on, then show why each one fails.

✦ Strawman Syllogism #1: God’s Hiddenness Is Not Absence Because He’s Transcendent

P1: Human absence in relationships implies abandonment.

P2: But God is not human—He is ontologically distinct.

Conclusion: Therefore, God’s absence cannot be judged by human standards and may not constitute abandonment.

Flaw: This syllogism fails by invoking transcendence as an escape hatch. You acknowledge that God desires relationship but then say we shouldn’t expect God to behave like a relational being. That’s incoherent. You invoke human-like attributes (love, desire for relationship, moral concern) to justify belief, then reject human-like expectations (clarity, mutuality, responsiveness) to defend God’s silence. That’s special pleading.

If God is relational, then relational logic applies. Otherwise, you’ve emptied “relationship” of meaning and redefined it into non-testable abstraction.

✦ Flaw in Strawman Syllogism #1

“Invoking transcendence as an escape hatch”

Informal Claim:

“God is not human; therefore, we should not expect God to behave like a relational being even if He claims to be one.”

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “x is relational”

= “x is human”

= “x has relational expectations (e.g., clarity, response)”

= “God”

Raul’s Implicit Structure:

But this commits a non sequitur. The correct inference would be:

(“If God is relational, then relational expectations apply.”)

Raul’s position negates the consequent based solely on ontological difference, which is logically invalid.

✦ Strawman Syllogism #2: Too Much Clarity Would Eliminate Free Will

P1: If God were maximally clear, belief in Him would be compulsory.

P2: Compulsory belief undermines love.

Conclusion: Therefore, God remains ambiguous to preserve free will and genuine love.

Flaw: This is a false dichotomy between coercion and total ambiguity. It assumes that clarity equals compulsion, which is demonstrably false. I know my friends and family exist with 100% certainty, yet I’m not “coerced” into loving them. Love thrives on presence, not epistemic opacity.

Also, it misframes God as a delicate social mechanic—tinkering just enough ambiguity into every culture, personality, and generation to maintain the fragile balance of belief. That’s theology by rational retrofitting.

✦ Flaw in Strawman Syllogism #2

“False dichotomy between coercion and ambiguity”

Informal Claim:

“Too much clarity would force belief, undermining love.”

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “x has clarity of God’s existence”

= “x’s belief is coerced”

= “x can love God freely”

Raul’s Implicit Claim:

Therefore:

This falsely assumes that clarity necessitates coercion.

Countermodel:

Let and

be simultaneously true. This is clearly possible in human relationships:

(“I know you exist and still choose to love you freely.”)

Thus, Raul’s argument fails due to an invalid implication chain.

✦ Strawman Syllogism #3: Both Belief and Skepticism Can Be Projections

P1: Skeptics may project a need for certainty.

P2: Believers may project a need for meaning.

Conclusion: Both are on equal epistemic footing; projection cancels out.

Flaw: This is a tu quoque fallacy. Yes, both belief and doubt can involve emotional projection—but only one is falsifiable. A claim that “God speaks to me” can be tested for internal consistency, psychological bias, and cultural derivation. The claim “I don’t see sufficient evidence” is not a projection—it’s a response to an evidentiary gap. Doubt is not its own worldview; it’s a position withheld until the data supports it.

✦ Flaw in Strawman Syllogism #3

“Tu quoque fallacy between belief and skepticism”

Informal Claim:

“Both belief and skepticism are susceptible to projection; therefore, they are epistemically equal.”

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “x is a projection”

= “belief in God”

= “doubt of God”

= “x is epistemically justified”

Raul’s Structure:

Flaw: Just because both are psychologically explainable does not mean both are epistemically equivalent. Projection is not the metric for epistemic justification.

Correct standard:

(“Doubt is justified when there is insufficient evidence S.”)

So:

and

✦ Strawman Syllogism #4: Jesus Resolves Divine Hiddenness Through History and Testimony

P1: God revealed Himself in Jesus.

P2: We have testimony about Jesus.

Conclusion: Therefore, God is not hidden.

Flaw: This is category conflation. Testimony is not the same as presence. If Jesus’s resurrection is the lynchpin of divine clarity, then we need first-person confirmation, not third-party ancient writings compiled decades later. When God allegedly appeared in history, His acts were not documented universally, not preserved independently, and not repeatable. The historical fog isn’t trivial—it’s decisive.

You say Jesus still appears through the Holy Spirit. Yet this produces wildly divergent doctrines, inconsistent experiences, and zero verifiable appearances. That’s not revelation. That’s theological subjectivism.

✦ Flaw in Strawman Syllogism #4

“Category conflation between testimony and presence”

Informal Claim:

“God showed up in history via Jesus; therefore, divine hiddenness is resolved.”

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “x is testimony of past events”

= “x is present, current interaction”

= “x is reliable revelation”

= “Jesus”

Raul’s Argument Implies:

and

But the conflation is here:

(Testimony of a figure ≠ Present, confirmable experience of God)

The correct analysis distinguishes:

✦ Strawman Syllogism #5: God Must Be Approached Holistically, Not Just Logically

P1: Knowing God requires openness of heart, not just logic.

P2: You (the skeptic) are only evaluating with logic.

Conclusion: Therefore, you may never find God.

Flaw: This reduces rational evaluation to a deficiency in existential posture, which allows you to blame the seeker while preserving the claim. You’ve made divine silence the seeker’s fault by saying the wrong kind of openness was applied.

Imagine applying that logic to any other domain:

“The medicine didn’t work? You must not have wanted healing the right way.”

“The teacher never answered you? You must not have been open to learning.”

No. When we’re told a relational being wants to be known, then the burden of contact lies on the communicator, not the hearer. If your theology requires the hearer to stretch into mystical receptivity before the speaker even shows up, that’s not a relationship. It’s a guessing game.

✦ Flaw in Strawman Syllogism #5

“Shifting burden via existential openness”

Informal Claim:

“You may not find God because you’re only using logic; you need relational openness.”

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “x uses logic”

= “x is relationally open”

= “x finds God”

= “God”

Raul’s Argument:

(“If you’re not relationally open, you won’t find God.”)

But this setup shields the claim from falsifiability. If fails, Raul claims

must be false, thus shifting the fault to the seeker regardless of conditions.

This forms a non-falsifiable loop:

Legitimate reasoning requires:

(“If one finds God, then there exists observable evidence for God.”)

When , continued belief becomes epistemically unjustified.

✦ Summary: What All These Syllogisms Share

Each of your defenses relies on post hoc rationalization:

- Silence is rebranded as subtlety.

- Uneven religious experiences are reframed as “relational intentionality.”

- Lack of evidence is spiritual depth.

- Confusion is mystery.

- Demand for clarity is rebranded as pride.

This is not a worldview engaging in robust inquiry. This is a self-sealing system that reframes every weakness as a strength. That’s not rationality—it’s insulation.

✦ Closing Syllogism: The Real Tension

P1: A loving, omnipotent being desiring relationship would ensure it is epistemically possible for all sincere seekers to recognize Him.

P2: Countless sincere seekers across history, cultures, and religions have not recognized Him—despite honest effort.

Conclusion: Therefore, either such a God does not exist, or He does not behave as Christians claim.

✦ Closing Syllogism: The Core Problem of Divine Hiddenness

Restated from Earlier:

P1: A loving, omnipotent being who desires relationship would ensure that all sincere seekers can recognize Him.

P2: Many sincere seekers do not recognize God despite honest, extended efforts.

Conclusion: Therefore, such a being either does not exist or is not as Christians describe.

Symbolic Formulation:

Let: = “God is loving”

= “God is omnipotent”

= “God desires relationship”

= “x is a sincere seeker”

= “x recognizes God”

= “God exists”

Form:

Therefore:

Interpretation:

If there exists a sincere seeker who does not come to recognize God, then either God does not exist, or the God that exists is not loving, omnipotent, and desirous of relationship as claimed.

Raul, when theology absorbs every failure as “another layer of divine genius,” it becomes indistinguishable from fantasy. If God exists and wants to be known, He knows how to be known. If He doesn’t show up, the intellectually honest response is not to invent theological workarounds—but to update the credence downward.

That’s what rational inquiry demands.

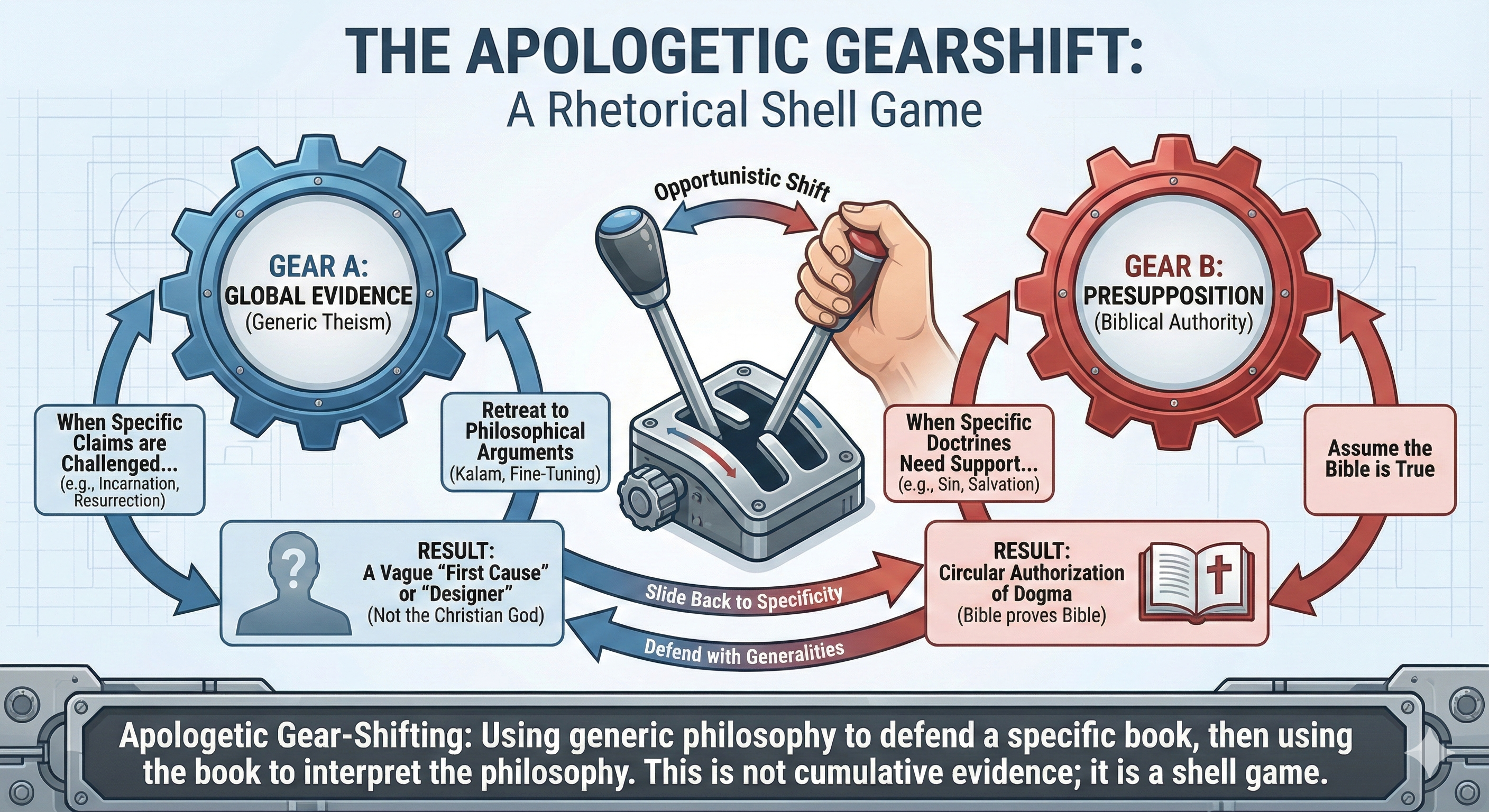

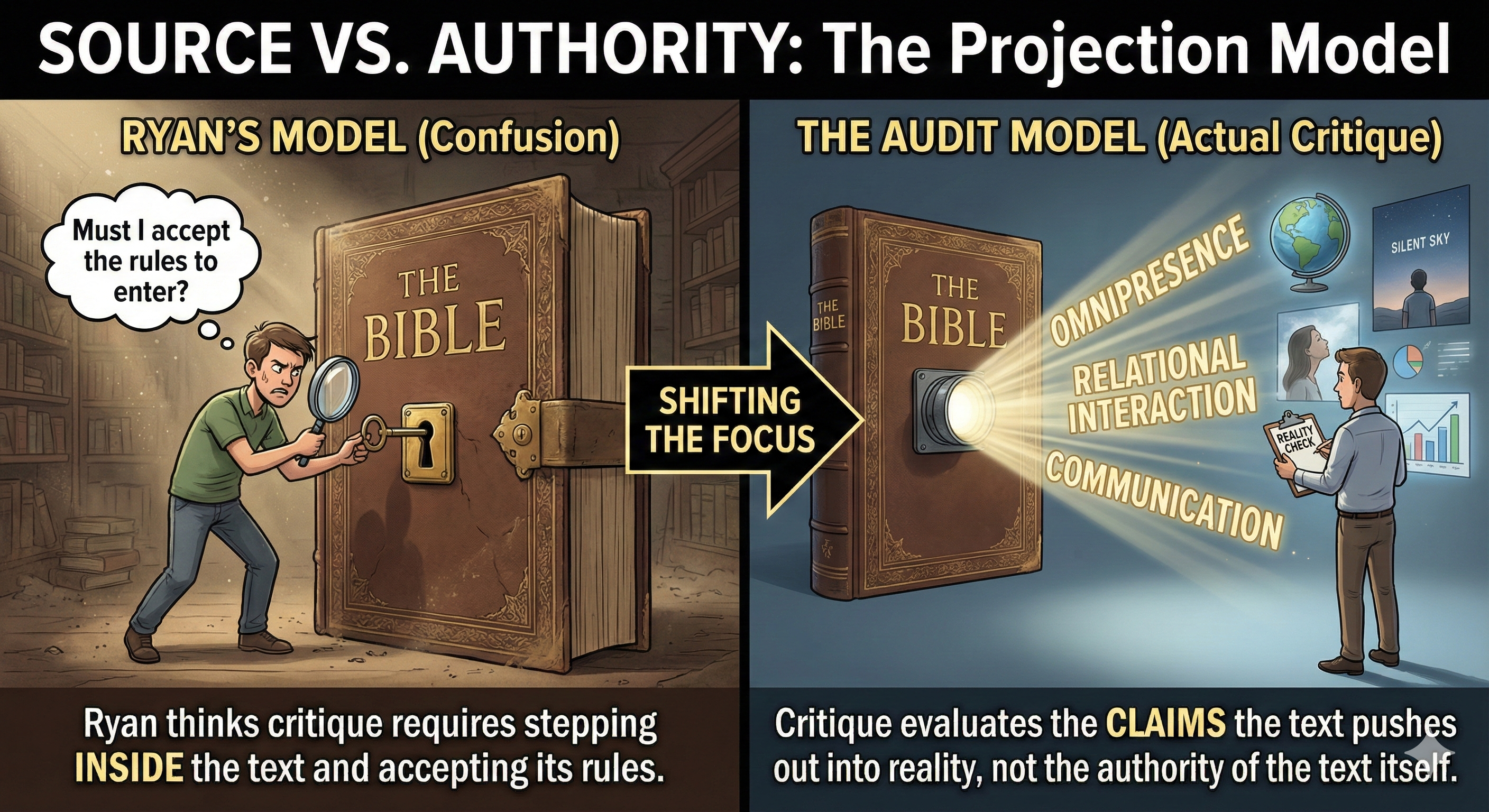

A Common Apologist Tactic

One of the most common tactics employed by Christian apologists when confronted with rational critiques of the Bible or the concept of divine hiddenness is to reframe the critic’s argument as nothing more than a subjective preference. Rather than engage with the actual inference—often a conditional claim like “If God is loving, rational, and communicative, then we would expect His revelation to be clear and accessible”—the apologist sidesteps the logic by asserting, “You’re just expecting God to behave the way you think He should.” This rhetorical move attempts to dissolve the force of the critique by painting it as arbitrary, prideful, or culturally biased, rather than addressing its logical structure. In doing so, the apologist avoids the burden of showing internal coherence within their theology and instead displaces the discussion into a fog of relativized expectations, where no standard short of divine decree is allowed to count.

This type of disagreement is not only common—it’s diagnostic of how many Christian apologists attempt to insulate their claims from falsifiability by recasting rational critique as mere subjective preference. Let’s analyze it in full.

How This Misunderstanding or Tactic Arises

There are several potential sources behind this move, and they vary in motivational character:

1. Ignorance (Epistemic Misunderstanding)

Some apologists genuinely fail to distinguish between inductive expectations grounded in rational analysis and mere personal preferences. They do not understand that when someone says, “We would expect X from a being with attributes A, B, and C,” this is not a demand but an inference. Their confusion is honest, but it reflects a lack of philosophical training in probabilistic reasoning and epistemology.

2. Noble Motivations (Faith-Preserving Reflex)

Others operate from a deep need to preserve their faith commitments. To them, recasting critique as preference lowers the stakes: if it’s all just subjective standards, then they don’t need to feel threatened. They may even believe they are helping the skeptic avoid “arrogant reasoning,” seeing themselves as defenders of humility before divine mystery.

3. Ignoble Motivations (Deflection Strategy)

In more adversarial settings, the tactic is used strategically. By labeling a critic’s expectations as “subjective preferences,” the apologist can dismiss the critique without engaging it. This is an immunizing move—a way to protect doctrine from rational accountability. It’s often paired with ad hominems about the skeptic being “proud,” “rebellious,” or “demanding that God meet them on their terms.”

The Apologist’s Step-by-Step Maneuver

Let’s break down the typical rhetorical structure of the apologist’s tactic:

Step 1: The Critic Offers an Inference

“If God is loving, rational, and communicative, then we would expect His revelation to be clear, epistemically robust, and universally accessible.”

Step 2: The Apologist Reframes the Inference as a Preference

“That’s just what you think a divine being should be like. But who are you to tell God how to behave?”

Step 3: The Apologist Shifts the Standard

“You’re applying human expectations to a transcendent being. God’s ways are higher than ours.”

Step 4: The Critic is Labeled

“Your standard is not objective; it’s prideful, modern, or rationalistic. You’re demanding God meet your criteria.”

This sequence shuts down rational discourse by making all critique look like emotional projection or philosophical arrogance.

How to Best Call Out & Address This Tactic:

To respond effectively and decisively, you must reframe your position as inductive, not prescriptive, and then call attention to the double standard being used.

Here’s the airtight template:

1. Clarify the Nature of the Inference

“What I offered is not a demand—it’s a conditional inference: If God has properties X, Y, and Z, then we would expect outcomes A, B, and C. That’s how inference works. I’m not imposing a standard on God—I’m examining whether the internal claims of the theology cohere with observed reality.”

2. Reveal the Double Standard

“You want me to accept that God is loving, just, and relational, but then exempt Him from behaving in any way we recognize as loving, just, or relational. That’s not humility—that’s a license for incoherence.”

3. Make the Asymmetry Clear

“If someone claimed a loving parent locked themselves away, never responded to their child’s cries, and left cryptic messages interpreted by conflicting messengers, we would call that neglect—not mysterious love. You’re granting divine claims a category exemption you wouldn’t grant to anyone else.”

4. Shift the Burden Back

“You say my critique is based on ‘subjective preference.’ But tell me: What objective features would distinguish divine revelation from human invention? If your answer is ‘nothing that a human could judge,’ then you’ve admitted the view is unfalsifiable—and thus epistemically void.”

Conclusion

The apologist’s tactic of labeling critique as “subjective preference” is often a shield against epistemic accountability. Whether motivated by confusion, comfort, or control, the result is the same: they insulate their beliefs from scrutiny by pretending all standards are arbitrary unless issued by God Himself.

But inference from claimed divine properties to expected outcomes is not preference—it’s Bayesian reasoning. If the evidence doesn’t match the claim, the claim should be reexamined—not the standard for evaluating it.

That is what rational discourse requires. Anything less is special pleading in theological garb.

Facebook Apologist Fallacies

Divine Hiddenness

- “You’re thinking in human terms.”

Fallacy: Category Error — Presumes divine reasoning is beyond human logic, making rational discourse impossible.

- “God has revealed himself through nature.”

Fallacy: Equivocation — Conflates beauty or order with intentional divine communication.

- “Jesus showed himself to 500 people.”

Fallacy: Unverifiable Testimony — Cites ancient hearsay as if it were firsthand evidence.

- “The Bible is the most preserved book in history.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Preservation — Age and preservation are not indicators of truth.

- “Nature proves God’s glory.”

Fallacy: Begging the Question — Assumes the very conclusion it needs to prove.

- “God uses weak vessels to shame the wise.”

Fallacy: Anti-Intellectualism — Dismisses critique by glorifying ignorance.

- “You’re expecting God to be like a vending machine.”

Fallacy: Straw Man — Misrepresents the critic’s point about communication as entitlement.

- “If God did it your way, you wouldn’t need faith.”

Fallacy: False Dilemma — Assumes that faith and clarity are mutually exclusive.

- “God’s silence is a test.”

Fallacy: Ad Hoc Explanation — Retrofits meaning onto silence to avoid falsifiability.

- “You wouldn’t understand even if He did speak.”

Fallacy: Poisoning the Well — Dismisses the critic’s capacity for reason preemptively.

- “God reveals to those who seek with the right heart.”

Fallacy: No True Seeker — Redefines sincerity to exclude dissent.

- “Why do you hate God so much?”

Fallacy: Loaded Question — Presumes hatred for a being under debate.

- “The problem is not the message, but your heart.”

Fallacy: Ad Hominem — Targets the critic’s character rather than the critique.

- “You sound like the serpent.”

Fallacy: Guilt by Association — Associates inquiry with evil intent.

- “It’s not a religion, it’s a relationship.”

Fallacy: Red Herring — Evades epistemic concern with emotional appeal.

- “God works in mysterious ways.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Mystery — Shuts down investigation by fiat.

- “You can’t put God in a box.”

Fallacy: Equivocation — Uses metaphor to escape logical scrutiny.

- “God chose to reveal himself through scripture.”

Fallacy: Assumption of Premise — Begs the question on divine authorship.

- “If you humble yourself, you’ll see the truth.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Virtue — Makes belief contingent on character, not evidence.

- “Those who doubt are just rebellious.”

Fallacy: Psychologizing the Opponent — Reduces inquiry to emotional defect.

- “There’s more evidence for the Bible than any ancient text.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Quantity of Manuscripts — Doesn’t address veracity.

- “Scripture has spiritual clarity even if it seems confusing.”

Fallacy: Special Pleading — Makes scripture exempt from normal expectations of clarity.

- “God gives us just enough light to follow.”

Fallacy: Ad Hoc Rationalization — Reframes ambiguity as divine strategy.

- “Truth is offensive to the proud.”

Fallacy: Tu Quoque — Assumes critique is rooted in arrogance.

- “Even the disciples struggled to understand.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Ignorance in High Places — Uses confusion of others to normalize confusion.

- “You only reject God because of pain.”

Fallacy: Straw Man — Invents motives for rejection instead of addressing arguments.

- “You wouldn’t demand this of other beliefs.”

Fallacy: Whataboutism — Compares unrelated belief systems instead of defending the claim.

- “God is beyond our logic.”

Fallacy: Special Pleading — Suspends logic to preserve belief.

- “If you really wanted truth, you’d see it.”

Fallacy: Mind Reading — Presumes inner motives to dismiss inquiry.

- “God reveals himself to the humble.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Subjectivity — Truth is framed as a function of character.

- “Many people have come to Christ through the Bible.”

Fallacy: Argument from Popularity — Numbers don’t confirm truth.

- “Miracles still happen.”

Fallacy: Non-Sequitur — Doesn’t answer the question of communication method.

- “God has no obligation to prove himself.”

Fallacy: Evasion — Avoids whether a loving god would.

- “Faith is believing without seeing.”

Fallacy: Circular Reasoning — Redefines belief as virtue to justify lack of evidence.

- “You’re judging eternal truths by temporal standards.”

Fallacy: Category Error — Blurs distinction between coherence and duration.

- “No book could ever be enough—only the Spirit is.”

Fallacy: Moving the Goalposts — Redefines the standard after critique.

- “God isn’t a genie to grant your demands.”

Fallacy: Straw Man — Equates request for clarity with selfish demands.

- “You have to be born again to see the truth.”

Fallacy: Epistemic Isolation — Only insiders can assess, making falsifiability impossible.

- “You can’t compare God to man.”

Fallacy: False Analogy Avoidance — Refuses analogy to escape responsibility.

- “This world is a test.”

Fallacy: Post Hoc Rationalization — Ascribes hidden purpose to justify hardship.

- “Your doubts are from Satan.”

Fallacy: Ad Hominem via Demonization — Discredits critique by source-calling.

- “The truth offends.”

Fallacy: Virtue Signaling — Frames offense as validation.

- “God’s word won’t return void.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Prophecy — Uses unverifiable prediction as justification.

- “It’s not up to us to understand.”

Fallacy: Appeal to Ignorance — Uses lack of knowledge as rationale.

- “Jesus is all the evidence you need.”

Fallacy: Assertion without Evidence — Assumes what’s in question.

- “You’re cherry-picking scripture.”

Fallacy: Selective Accusation — No counterexample given.

- “Everyone interprets things differently.”

Fallacy: Relativism Fallacy — Uses disagreement to dodge accountability.

- “God hardened hearts.”

Fallacy: Determinism Excuse — Undermines moral accountability.

- “You will understand in heaven.”

Fallacy: Deferral Fallacy — Postpones resolution beyond scrutiny.

- “You’re just trying to divide the body of Christ.”

Fallacy: Motivational Projection — Assigns divisive intent to suppress critique.

Leave a comment