Consider the Following:

Summary: This post questions whether the Bible, expected to be a clear and unified message from an omniscient God, actually demonstrates the doctrinal clarity one would anticipate from divine authorship. It highlights the Bible’s ambiguity by pointing to the vast disagreements among Christians on core beliefs, suggesting this lack of unity challenges the claim of a divinely authored text.

Imagine you know you have only a few days left to live. You deeply wish for your young children to clearly understand three essential things: who you are, your intentions for their lives, and rules to guide them. Being a skilled writer, you understand precisely which words will unmistakably convey these messages, preventing any possible confusion or division among your children. How would you choose to communicate?

Would your message look anything like the Bible? Or, as one would expect from a powerful communicator, would it surpass even the precision found in legal and scientific texts? Why, then, would an all-knowing God write a book as vague as the Bible? Has it fostered greater unity among its followers than other alleged holy books, or does it mirror the same level of doctrinal ambiguity? If we find only fragmentation rather than cohesion, is that not a reasonable basis for doubting the Bible’s divine origin?

Hundreds of doctrinally diverse Christian denominations cite the Bible as their source of truth. Yet on issues as fundamental as salvation, baptism, morality, and worship, opinions sharply diverge.

The Significance of Doctrinal Disunity

Consider the following topics, many central to Christianity:

- 1. Baptismal Practices

- Debates exist over the mode (e.g., immersion vs. sprinkling), timing (infant vs. believer’s baptism), and significance of baptism, with questions about its role in salvation and spiritual regeneration.

- 2. Predestination vs. Free Will

- The doctrines of predestination and election (Calvinism) are contrasted with beliefs in free will and human responsibility (Arminianism), creating division over God’s role in salvation.

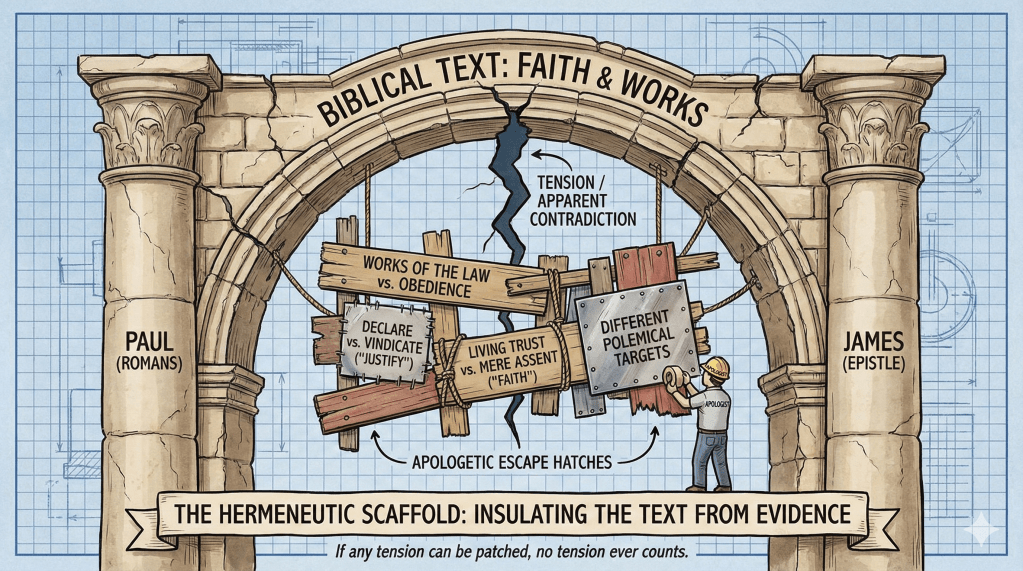

- 3. The Role of Works in Salvation

- There is disagreement on whether good works play any role in salvation, with some groups emphasizing salvation by faith alone (sola fide) and others viewing faith and works as interconnected.

- 4. The Eucharist (Communion)

- Doctrinal disunity exists on the nature of communion: transubstantiation (literal body and blood), consubstantiation, and symbolic remembrance. Different denominations interpret the meaning and practice differently.

- 5. Original Sin and Human Nature

- Christian views vary on original sin—whether humans are born inherently sinful and in need of redemption or are born innocent and choose sin as they mature.

- 6. Divorce and Remarriage

- There are divergent beliefs about whether divorce is ever permissible for Christians and whether remarriage constitutes adultery under biblical law.

- 7. The Nature of Hell and Eternal Punishment

- Disunity surrounds views on hell and eternal punishment—some hold to eternal conscious torment, while others advocate for annihilationism or universal reconciliation.

- 8. Gender Roles in Church Leadership

- While some believe women can hold positions of authority in the church, others restrict roles like pastor or elder to men, interpreting passages in the New Testament differently.

- 9. Sabbath Observance

- There are differing views on the Sabbath—whether it should be observed on Saturday or Sunday, if it’s binding on Christians, and whether its observance should be literal or spiritual.

- 10. Creation and Evolution

- The interpretation of Genesis varies widely, from young Earth creationism to theistic evolution and progressive creationism, with disagreements about the Bible’s compatibility with scientific theories.

- 11. The Charismatic Gifts

- Many Christians disagree over the role of spiritual gifts (e.g., prophecy, healing, tongues) today, with some believing they ceased after the apostolic era (cessationism) and others believing they continue (continuationism).

- 12. Pacifism and Just War

- There are divisions over whether Christians are called to pacifism or may support just war, with differing interpretations of Jesus’ teachings on nonviolence.

- 13. Marriage and Sexuality

- In addition to views on homosexuality, there is debate on whether celibacy is a higher calling, the role of marriage, and views on sexuality and family planning.

- 14. The Role of Israel in Prophecy

- Christian beliefs vary on the modern nation of Israel’s significance in prophecy, with some viewing it as central to end times events and others seeing no prophetic significance.

- 15. Authority of Church Tradition vs. Scripture Alone

- While some denominations adhere strictly to sola scriptura (Scripture alone), others incorporate church tradition as equally authoritative, affecting doctrines and practices.

- 16. The Rapture and Tribulation

- The timing and nature of the rapture (pre-tribulation, mid-tribulation, or post-tribulation) and its place in end times prophecy is a point of disagreement.

- 17. The Degree of Belief Necessary for Redemption.

- Even within a single denomination, the degree of belief for redemption necessary is debated. Is absolute belief necessary? Or will belief the size of a mustard seed suffice?

- 18. Prosperity Gospel and Suffering

- The prosperity gospel asserts that God rewards faith with wealth and health, conflicting with traditional views on suffering, self-denial, and the Christian life.

- 19. Divine Inspiration and Biblical Inerrancy

- Some Christians believe in biblical inerrancy (the Bible is without error in all aspects), while others see it as infallible only in spiritual or moral teachings, leading to different approaches to Scripture.

- 20. Exorcism and Demonology

- Christians hold varying beliefs about demons and exorcism—whether these practices are essential, rare, or even necessary in the modern era.

If you surveyed a thousand Christians—even within a single denomination—how unified would their responses be? Would they demonstrate the clarity and unity one would expect from a message believed to be written by an omnipotent and omniscient deity, determined to reliably communicate his essence and moral intentions to humanity?

- Christian Thought Survey

- (406 Christian Pastor/Minister Participants)

An enlightening experiment might involve isolating two newly converted Christians, who rely solely on the Bible to form their beliefs, without any external doctrinal influences. Would their interpretations align? Does the Bible’s language and structure inherently foster a single, unified understanding of its doctrines, as one would expect from a divinely inspired text?

Throughout history, interpretations of Biblical doctrines have evolved—views on issues like demon possession, slavery, and treatment of non-Christians shift in response to cultural and scientific progress. Would this variability exist if the Bible had been authored by a God aware of its diverse contexts over centuries?

The Bible, rather than presenting unambiguous guidance, offers a level of imprecision comparable to other holy books, as evidenced by the vast doctrinal disagreements among Christians today.

See also Considerations #02:

Additional Considerations:

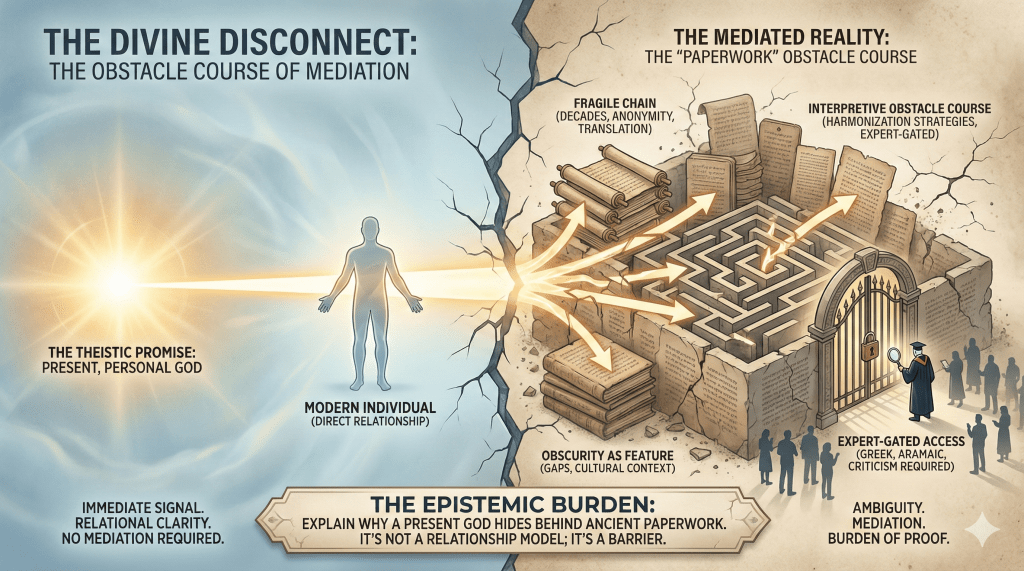

How might a genuinely omnipotent God guarantee a clear, reliable conveyance of his essence and moral intentions? Several possible methods come to mind:

- Any actual God could directly appear and speak with each individual.

- Any actual God could speak in real-time to people’s minds, even if remaining unseen.

- Any actual God could place an indelible memory of essential doctrines within every believer.

- Any actual God could assign angels to audibly deliver his messages.

- Any actual God could create a book with such precise language that believers would not encounter apparent contradictions.

- Any actual God could author a text in a unique, universally understood language that precludes honest doctrinal disagreement.

Wouldn’t any of these options, or countless others, be within the power of an all-knowing God? Instead, the Bible, much like other holy texts, fosters a spectrum of interpretations, each generating its own doctrines.

This lack of doctrinal clarity challenges the notion that the Bible is the definitive word of a God of wisdom and power. The evidence suggests that rather than an indisputable guide, the Bible functions no differently in clarity than other ancient texts of uncertain origins.

A Companion Technical Paper:

See also:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Doctrinal Unity and Divine Authorship

- Premise 1: If a divine book is authored by an omniscient God, it would inherently foster doctrinal unity among its followers.

- Premise 2: The Bible does not foster such doctrinal unity; instead, it leads to vast interpretations and disagreements among believers.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Bible was likely not authored by an omniscient God.

Argument 2: Divine Communication and Doctrinal Clarity

- Premise 1: An all-knowing God would ensure his teachings are communicated with unambiguous clarity if he wished to guide humanity.

- Premise 2: The Bible demonstrates significant ambiguities and contradictions on fundamental doctrines (e.g., salvation, morality).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Bible does not reflect the unambiguous clarity expected from an all-knowing God.

Argument 3: Alternative Methods of Divine Communication

- Premise 1: An omnipotent God has various methods to ensure doctrinal clarity (e.g., direct revelations, universal language, indelible memory implants).

- Premise 2: The Bible does not employ these methods and instead resembles other religious texts in its doctrinal ambiguity.

- Conclusion: Thus, it is unlikely the Bible was authored by an omnipotent God aiming for doctrinal clarity.

Argument 4: Doctrinal Evolution and Divine Authorship

- Premise 1: A book authored by an unchanging God would present doctrines immune to cultural or scientific shifts.

- Premise 2: The Bible’s doctrines (e.g., views on demon possession, slavery) have evolved with cultural and scientific progress.

- Conclusion: This evolution suggests the Bible was likely not authored by an unchanging God.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

Dialogue

Does the Bible Reflect Divine Clarity?

CHRIS: I believe the Bible is the inspired word of an omniscient God, offering everything we need for a meaningful relationship with Him. It may have some challenging passages, but the core doctrines are clear and reveal God’s will for us.

CLARUS: But if the Bible was authored by an omniscient and omnipotent God, wouldn’t it logically foster doctrinal unity among its followers? We see instead a proliferation of interpretations and countless denominations with starkly different views on essential doctrines like salvation, morality, and worship.

CHRIS: Denominational diversity doesn’t necessarily imply doctrinal confusion. These differences often stem from human misunderstanding, not from any lack of clarity in the Bible itself. God provided a solid foundation; it’s up to us to interpret it responsibly.

CLARUS: But if humans were prone to misinterpret it, why wouldn’t an all-knowing God ensure His teachings were conveyed with unambiguous clarity? Shouldn’t a divinely inspired book be clear enough to avoid the endless disagreements we see? After all, God would want us to grasp the essentials without confusion, right?

CHRIS: Perhaps God values our journey of interpretation and the growth it brings. The Bible can still be divinely inspired while encouraging us to search, study, and debate.

CLARUS: But consider this: if you were a parent with only days to live, wouldn’t you choose language so clear that your children couldn’t misunderstand your intentions? You wouldn’t want them divided or guessing about something so crucial. Why wouldn’t an omnipotent God, then, make His message similarly precise?

CHRIS: Well, perhaps God uses the diversity of interpretation to foster different perspectives, allowing each person to experience faith in their unique way.

CLARUS: That might make sense if the Bible only dealt with personal perspectives, but we’re talking about fundamental issues here. If God truly intended for His book to communicate one unifying message, then why does the Bible resemble other ancient texts in its ambiguities? Take speaking in tongues or female leadership—believers don’t agree on these, which raises doubts about the Bible’s divine clarity.

CHRIS: Maybe those differences are just tests of faith or opportunities for deeper reflection. Unity in every aspect may not be the goal.

CLARUS: But doctrinal clarity seems essential if the goal is a unified faith. Imagine if God had given the Bible in a unique, universal language that everyone could understand, precluding doctrinal disagreements. That would align more with the expectations for a text from an all-knowing deity.

CHRIS: Isn’t it possible that these alternatives—like a universal language—would take away from our free will to interpret and grow?

CLARUS: Free will doesn’t require ambiguity in core doctrines. The fact that doctrines on salvation, morality, and even baptism vary so widely suggests a deeper issue. If the Bible is meant to guide humanity clearly, the lack of doctrinal unity raises questions about its divine authorship.

CHRIS: I see your point, but I believe that ultimately, faith bridges these differences, allowing each believer to find their own path to God.

CLARUS: Faith is one thing, but if the Bible was divinely inspired, I’d expect doctrinal clarity on fundamental beliefs. The fact that doctrines evolve, reflecting cultural and scientific shifts, suggests that the Bible behaves more like a human document than a divine one. Wouldn’t that make you wonder about its origins?

CHRIS: It’s challenging, but I still believe God’s wisdom surpasses our understanding, even if it means grappling with these ambiguities.

CLARUS: Fair enough, but from a logical standpoint, the Bible’s doctrinal ambiguity doesn’t align with what we’d expect of a message from an omniscient, omnipotent God. That’s something worth pondering.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

1. The Instruction Manual Analogy

Imagine buying a complex piece of machinery with an instruction manual supposedly written by the manufacturer—the only source you can rely on to understand how to use it safely. If the manual were filled with vague instructions and inconsistent steps, resulting in users assembling it in various, conflicting ways, you would question whether it truly came from the manufacturer. Similarly, if the Bible were written by an omniscient God to guide believers, wouldn’t it provide clear, unified instructions to prevent interpretative discrepancies?

2. The Legal Code Analogy

A legal system depends on precise language to ensure that citizens understand their rights and obligations clearly. If a country’s laws were written in ambiguous language, leading judges and lawyers to interpret them in contradictory ways, it would undermine public trust in the system. In the same way, if the Bible is supposed to be a guide from an omniscient deity, it would likely exhibit doctrinal clarity comparable to, or exceeding, that of a reliable legal code to avoid the risk of interpretative chaos.

3. The Recipe Book Analogy

Consider a recipe book by a world-renowned chef, intended for cooks of all skill levels. If the recipes were written in a way that left key steps or measurements open to interpretation, cooks would produce wildly different results from the same recipe, casting doubt on the chef’s expertise. Likewise, if the Bible were authored by an all-knowing God with the goal of instructing humanity in a single path, it would be expected to provide clear, precise guidance that yields consistency rather than divergent doctrines among its followers.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. God’s Purposes Extend Beyond Doctrinal Uniformity

The Bible may not aim for doctrinal uniformity but rather invites believers into a journey of spiritual discovery and relationship with God. Rather than dictating every detail, the Bible encourages individual growth through interpretation and discernment, allowing God’s truth to be revealed in personal and community contexts.

2. Free Will and Faith Require Interpretative Flexibility

A perfectly clear text might eliminate the need for faith and free will in approaching God. By allowing interpretative flexibility, God gives humans the freedom to seek and find Him, choosing to exercise faith rather than being bound by rigid doctrinal statements. This freedom respects human autonomy and the unique journey each believer takes.

3. Cultural and Temporal Relevance in Divine Communication

The Bible’s evolving interpretations can reflect God’s responsiveness to the cultural and historical contexts in which believers live. God’s message may be inherently transcultural, but its understanding can adapt to time-bound realities, helping believers apply timeless principles in ever-changing societies while still being rooted in God’s overarching will.

4. Doctrinal Diversity as a Reflection of Divine Complexity

A divine message from an omniscient God might inherently contain depths beyond human comprehension. Just as diverse perspectives emerge when interpreting complex literature, the Bible may invite multiple layers of understanding that reflect God’s complex nature, allowing for diverse insights that ultimately contribute to a richer spiritual unity despite doctrinal differences.

5. The Bible as a Sacred Text, Not a Rulebook

Some theologians argue that the Bible functions as sacred literature, offering guidance rather than being an exact rulebook. This approach suggests that God intended the Bible to provide a framework for faith rather than dictating a single, strict interpretation. In this view, doctrinal diversity is not a flaw but a feature, encouraging engagement, reflection, and community dialogue.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “God’s Purposes Extend Beyond Doctrinal Uniformity”

If the Bible is intended as a guide to understanding God’s will, then doctrinal clarity would logically be necessary for achieving that purpose. Ambiguity on core doctrines undermines the claim that God wants a relationship with humans rooted in truth and understanding. Without a shared, consistent interpretation, the Bible seems less like a direct message from an omniscient deity and more like a human artifact prone to interpretative flaws and misunderstandings.

2. Response to “Free Will and Faith Require Interpretative Flexibility”

Free will and faith do not inherently require interpretative ambiguity; a clear message does not prevent individuals from freely accepting or rejecting it. Other legal or ethical systems maintain clear instructions while still allowing people the freedom to follow or ignore them. The claim that a clear Bible would eliminate free will seems unfounded, as individuals could still exercise their choice and faith in response to a clear and unified doctrine.

3. Response to “Cultural and Temporal Relevance in Divine Communication”

If God’s message were truly transcultural and eternal, then an omniscient deity would be capable of articulating doctrines in ways that transcend cultural shifts while remaining clear and consistent. The Bible’s need for reinterpretation across eras suggests limitations inconsistent with divine omniscience. A genuinely timeless text would not require adaptations to maintain relevance but would inherently communicate principles with a clarity that withstands temporal and cultural changes.

4. Response to “Doctrinal Diversity as a Reflection of Divine Complexity”

The notion that doctrinal diversity reflects divine complexity could be more plausibly interpreted as human fallibility in understanding a text that lacks clarity. In any coherent message, complexity does not necessarily equate to contradiction or ambiguity. If God intended multiple interpretations, it contradicts the premise of a singular truth often central to religious belief, suggesting instead that the Bible’s ambiguity is more indicative of human authorship than divine depth.

5. Response to “The Bible as a Sacred Text, Not a Rulebook”

If the Bible is primarily sacred literature and not a rulebook, then it should not be treated as the definitive source of truth on critical issues such as morality, salvation, and God’s will. Sacred literature may inspire, but for a text to serve as the foundation of a unified belief system, it would need to present clear doctrines. The doctrinal diversity resulting from the Bible’s ambiguity weakens its role as a guiding document from an omniscient deity, suggesting it operates more as a spiritual text than a divine revelation.

Clarifications

Syllogistic Proof

Assumptions (Premises):

- God’s Intentions: If God wrote the Bible, He would intend it to be the final authority on doctrine and morality.

- God’s Desire for Clarity: God desires doctrines and moral precepts to be unequivocal (free of ambiguity).

- God’s Omnipotence: God has the power to write a book that is unequivocal in its doctrines and moral precepts.

- Expectations of Divine Authorship: If God wrote the Bible, it would be unequivocal in its doctrines and moral precepts.

- Observation: The Bible is not unequivocal in its doctrines and moral precepts.

Conclusion: Therefore, the Bible was not written by God.

Symbolic Logic

Let:

= “God wrote the Bible.”

= “The Bible is unequivocal in its doctrines and moral precepts.”

= “God has the power to ensure the Bible is unequivocal.”

= “If God wrote the Bible, He intends it to be the final authority and unequivocal.”

Logical Structure:

(If God intends and has the power, then if God wrote the Bible, it would be unequivocal.)

(The Bible is not unequivocal.)

(If God wrote the Bible, it would be unequivocal.)

(If the Bible is not unequivocal, then God did not write the Bible.)

(Therefore, God did not write the Bible.)

Clarifying Notes

This formulation rigorously ensures the assumptions and logical structure are clear and sequential, while the symbolic logic provides a precise representation of the reasoning process. It also highlights the reliance on the observational premise () as central to the conclusion.

1. Doctrinal Unity vs. Doctrinal Diversity

Doctrinal unity implies a shared, consistent interpretation of religious teachings across a faith community, leading to minimal disagreement on core beliefs. Doctrinal diversity, in contrast, refers to the variety of interpretations and beliefs that emerge within a religious group, which can lead to differing views on fundamental doctrines (e.g., salvation, morality). The argument here questions whether a text authored by an omniscient God would permit such diversity on essential issues.

2. Free Will and Interpretative Ambiguity

The theological argument posits that interpretative ambiguity supports free will, allowing individuals to actively engage with the text. The counter-argument suggests that free will does not require ambiguity; one can choose to follow or reject even a clearly defined message. The question centers on whether a clear divine message would inherently limit free will, which the rational response argues it would not.

3. Timelessness and Cultural Adaptation

A truly timeless message would not require adjustments or reinterpretations to fit changing cultural or historical contexts. The rational argument contends that if the Bible’s doctrines were genuinely timeless, they would remain applicable and clear across all eras without needing reinterpretation to maintain relevance, which might suggest human, rather than divine, authorship.

4. Divine Complexity and Contradiction

Theological interpretations may view the Bible’s doctrinal diversity as a reflection of divine complexity, implying that a transcendent message could yield multiple layers of understanding. The counterpoint here is that complexity does not necessitate contradiction or ambiguity. From a rational standpoint, a coherent message—especially one from an omniscient being—would communicate complexity without causing confusion over core doctrines.

5. Sacred Literature vs. Definitive Doctrine

Sacred literature often inspires reflection and can foster diverse interpretations, but it does not necessarily serve as a singular source of truth for all believers. This clarification differentiates between using the Bible as spiritual inspiration and as a doctrinal guide. The rational response argues that if the Bible is to function as the latter, it would need clarity and consistency on essential doctrines to fulfill its role as a divine guide.

Christian Apologetics Group Responses

◉ These quotes are some of the most salient, representative quotes in response to this issue from a Facebook group called “Christian Apologetics.” This group consist of quite civil and well-educated apologies, many of them, pastors, or ministers.

Not all of the responses were problematic. The list below contains only clearly flawed responses, posted here for educational purposes. The last check revealed that there were a total of 98 comments in the thread.

- “You’re judging God by your own standards.”

Why it fails: Shifts the burden. The critique is about internal consistency, not personal preferences.

- “God doesn’t owe us an explanation.”

Why it fails: Avoids the issue of whether a loving deity would provide clarity and guidance.

- “You’re taking verses out of context.”

Why it fails: Generic dismissal. No clarification is offered to show how context would resolve the ambiguity.

- “Apologetics is about defending the faith, not questioning it.”

Why it fails: Focuses on method, not the issue. Dodges content-level critique.

- “You must believe before you understand.”

Why it fails: Circular reasoning. Belief is made a prerequisite for comprehension.

- “Satan wants you to ask these questions.”

Why it fails: Psychological manipulation. Attributes inquiry to malevolence.

- “You don’t have the Holy Spirit, so you can’t understand.”

Why it fails: Excludes outsiders from rational discourse. Unfalsifiable claim.

- “You’re not here to learn; you’re here to argue.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem. Avoids engaging the argument itself.

- “You think you’re the only one who understands the Bible.”

Why it fails: Deflects criticism by accusing the challenger of arrogance, without engaging the textual ambiguity being questioned.

- “Jesus is the answer to everything you’re asking.”

Why it fails: Non-specific and circular. Invokes a conclusion as a premise.

- “God’s ways are above our ways.”

Why it fails: Appeal to mystery. Stops the inquiry rather than addressing it.

- “You’re confusing your interpretation with truth.”

Why it fails: Attempts to relativize the issue instead of addressing whether the text itself is unambiguous.

- “The Bible is spiritually clear, even if not literally.”

Why it fails: Concedes ambiguity. Undermines claims of divine clarity.

- “You’re being arrogant by questioning God.”

Why it fails: Focuses on tone or attitude rather than content.

- “Faith doesn’t rely on evidence; that’s what makes it faith.”

Why it fails: Evades the demand for evidential justification.

- “You’re ignoring the spiritual dimension of scripture.”

Why it fails: Shifts the discussion to a vague metaphysical category rather than addressing doctrinal clarity.

- “Doctrinal unity comes from the Spirit, not logic.”

Why it fails: Appeals to unverifiable sources rather than explaining interpretive fragmentation.

- “You’re just bitter because you don’t like the Bible’s answers.”

Why it fails: Speculates on motive. Fails to engage argument directly.

- “You’re overcomplicating something that’s really simple.”

Why it fails: Dismisses the challenge without acknowledging the real complexity and disagreement among believers.

- “You’re twisting scripture to fit your worldview.”

Why it fails: Bare accusation. No explanation of an alternative interpretation.

- “The Bible isn’t confusing; people just want to be confused.”

Why it fails: Blames the reader without engaging the evidence of interpretive disunity.

- “That’s just your interpretation.”

Why it fails: Self-defeating when clarity is what’s under critique.

- “It’s not God’s fault if people misinterpret His Word.”

Why it fails: Avoids the question of whether a competent communicator would allow that.

- “You’re spiritually blind.”

Why it fails: Ad hominem. Disqualifies the critic rather than addressing the criticism.

- “God hardened some hearts on purpose.”

Why it fails: Evokes divine responsibility for confusion but treats it as excusable.

- “You’re not looking for truth—you’re looking for flaws.”

Why it fails: Projects motives. Ignores argument content.

- “If the Bible was perfect, people would still reject it.”

Why it fails: Hypothetical. Doesn’t justify actual flaws.

- “You can’t expect God to cater to modern minds.”

Why it fails: A timeless message should transcend eras.

- “Everything in the Bible has a purpose, even if we don’t see it.”

Why it fails: Appeal to hidden purpose. Blocks meaningful critique.

- “Your reasoning is limited by pride.”

Why it fails: Discredits the person, not the point.

- “You’re misusing logic; God doesn’t operate that way.”

Why it fails: Special pleading. Avoids standard reasoning.

- “You’re weaponizing doubt instead of seeking truth.”

Why it fails: Accusatory tone. Doesn’t refute the critique.

- “Even the disciples didn’t understand everything at first.”

Why it fails: Excuses confusion rather than resolving it.

- “God doesn’t need to pass your human tests.”

Why it fails: Avoids engagement by denying relevance of evidence.

- “Just read it with an open heart.”

Why it fails: Emotion-based appeal. Doesn’t engage logical challenge.

- “You’re not qualified to interpret the Bible.”

Why it fails: Appeals to authority. Fails to address textual ambiguity.

- “You’re focused on what God didn’t say instead of what He did.”

Why it fails: Ignores omission critique central to the post.

- “You’ve made up a god you want to disprove.”

Why it fails: Straw man. Avoids actual points raised.

- “If you knew God, you’d understand.”

Why it fails: Exclusionary. Offers no route for critical inquiry.

- “Don’t put God in a box.”

Why it fails: Overused cliché. Evades responsibility for clarity.

- “The problem is with your heart, not the Bible.”

Why it fails: Psychological accusation. Avoids argument content.

- “Faith isn’t about facts—it’s about relationship.”

Why it fails: Defers to emotion. Avoids evidence.

- “You’ll see the truth when God reveals it to you.”

Why it fails: Unfalsifiable. Forecloses debate.

- “Skepticism is just rebellion in disguise.”

Why it fails: Dismisses rational doubt as emotional defiance.

- “You sound like the serpent in the garden.”

Why it fails: Guilt by association. Doesn’t touch the critique.

- “Some things are hidden to increase our faith.”

Why it fails: Suggests ignorance is virtuous. Avoids evidence.

- “Even atheists use scripture; that means it has power.”

Why it fails: Non sequitur. Influence doesn’t equal truth.

- “You can’t apply man’s logic to God’s Word.”

Why it fails: Disallows shared standards of reasoning.

- “You’ll regret this on Judgment Day.”

Why it fails: Fear appeal. No logical rebuttal.

- “You’re just trying to divide believers.”

Why it fails: Shifts blame for disunity onto the critic rather than addressing the actual evidence of doctrinal inconsistency in the text.

Leave a comment