Consider the Following:

Summary: This post examines whether the actions of the God depicted in the Bible align with genuine love, questioning if a truly loving deity would inflict suffering on innocents. Through logical syllogisms, it highlights inconsistencies in biblical portrayals of divine love and justice, challenging readers to reconsider traditional views on the nature of God.

Imagine yourself as a monarch who genuinely loves your subjects. You seek their respect, but when they fail to honor you, you impose suffering on them and their children. Does such an approach reflect genuine love? Would love truly inflict suffering on innocent children to make a point to their parents?

This isn’t a fictional scenario if we consider biblical narratives. According to the Bible, every child on Earth perished in the flood, brought by a God described elsewhere as loving. Does this align with what we understand of love? Could you ever lovingly suffocate someone? Should we ignore our human notion of love to accept a radically different definition of love offered by the very God we question? Would a genuinely loving God author a book about love that diverges so drastically from human concepts of love?

Questioning the Divine Standard of Love

When parents discipline their children, sometimes these actions might seem unloving from the child’s perspective. However, this analogy does not apply to situations where a God inflicts suffering on innocent beings. The actions attributed to God in the Bible directly contradict a fundamental human understanding of love. Whose standard are we to use when discerning whether actions are loving? It is incoherent to adopt a perverted (from a human perspective) definition of love attributed to the God of the Bible while attempting to objectively evaluate the coherence of that same God.

Consider the following passages where God’s actions appear indiscriminately punitive, even involving innocent infants:

- “Attack the Amalekites… Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants…”

— 1 Samuel 15:3 (related video)- “Every living thing on the face of the earth was wiped out…”

— Genesis 7:23- “The LORD rained down burning sulfur on Sodom and Gomorrah…”

— Genesis 19:24-25

Here, God did not merely punish transgressors; innocent children suffered by His hand. This raises a critical question: if God’s power allows Him to eliminate innocent suffering entirely, why choose suffering as part of His expression of love? Can such actions genuinely reflect a loving deity?

Responses to Objections

Common responses suggest that the suffering of the Amalekite children was justified by their parents’ actions or that God granted them immediate entry into Heaven. However, these arguments do not account for the suffering itself, which remains unjustifiable.

Others argue that sparing the children would somehow corrupt the Israelites. But when pressed, few supporters of this view advocate for ending a fetus’s life due to a parent’s wrongdoing. Here, the actual suffering inflicted remains the focal concern, unaddressed by such defenses.

Another passage clearly states, “The son will not share the guilt of the father…” (Ezekiel 18:20). Do you feel innocent children should be punished for the offenses of their parents?

Dialogue on Divine Love and Justice

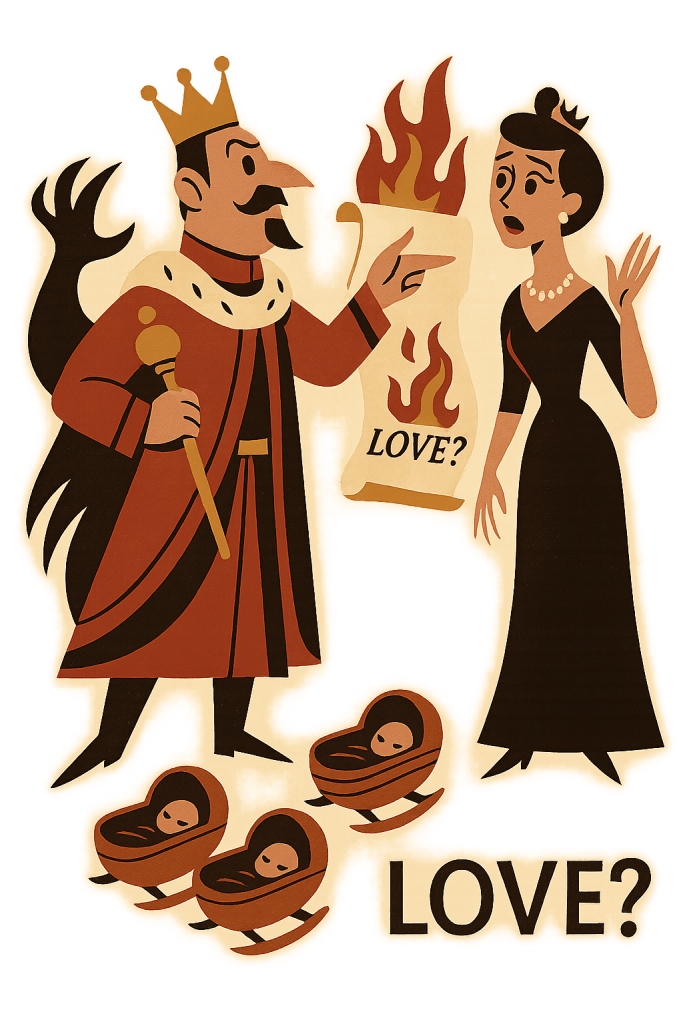

- KING: Remember the family who refused to acknowledge me?

- QUEEN: Yes, I recall.

- KING: I had them all killed, including the infants.

- QUEEN: You said you loved them, yet you killed even the innocent?

- KING: I am a loving king, so yes.

- QUEEN: That defies love itself. How can killing innocent infants be considered loving?

- KING: As king, I decide what love means.

- QUEEN: But twisting concepts into their opposites doesn’t make them true. What you did would be called hatred, not love.

- KING: I have the power to redefine love as I see fit.

- QUEEN: If you so assert, you are then no longer participating in clear and honest communication. Intentional behavior of this sort is undeserving of anyone’s respect.

Broader Implications on Suffering and Inaction

The biblical God, if real, is said to witness children suffer unimaginable pain without intervening. Many argue that He may have a “mysterious reason” for allowing such horrors. But if a neighbor allowed similar atrocities, would we grant them the same benefit of the doubt? No compassionate person would tolerate such suffering, even for a hidden reason. Should we, therefore, honor a God who stands by as children suffer? How much respect should we give a God, substantiated or not, who has ordered grown men to kill infants?

A Companion Technical Paper:

Linguistic Self-Deception

If a king punished not only rebels but also their innocent children, would we still call that king loving, or would the term itself become hollow under such a contradiction? This analogy raises a difficult question about biblical depictions of divine love—especially in narratives like the flood, where every child perishes at the hand of a God described as loving. Can “love” still retain its meaning if it includes such acts, or does redefining it in this way erode the concept into incoherence? Should we accept a version of love that seems indistinguishable from cruelty simply because it is attributed to a deity? And if God’s actions are said to operate on a plane “beyond human understanding,” how can terms like love, justice, or compassion have any consistent or communicable meaning to us at all? Would we tolerate a neighbor who allowed children to suffer horribly for a hidden reason, and if not, why do we excuse a deity for the same behavior? If we continue to call such acts “loving,” are we not engaged in linguistic self-deception, using a word that no longer connects to anything we would recognize as care or compassion?

The Logical Form

Argument 1: The Flood and Innocent Suffering

- Premise 1: A genuinely loving being would not cause innocent suffering as a form of punishment or lesson.

- Premise 2: The God depicted in the Bible caused innocent suffering (e.g., the deaths of all children in the Flood).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the God depicted in the Bible does not act as a genuinely loving being.

Argument 2: Standards of Love and Divine Actions

- Premise 1: Actions that align with genuine love do not involve inflicting harm on innocent beings.

- Premise 2: The God in the Bible inflicts harm on innocent beings (e.g., killing infants and children in various biblical accounts).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the actions of the biblical God do not align with genuine love.

Argument 3: Love Redefined as Hatred

- Premise 1: Redefining concepts like love into their opposites (e.g., love redefined as inflicting harm) distorts their true meaning.

- Premise 2: The Bible describes God as loving while depicting actions that align with hatred (e.g., causing suffering to innocents).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Bible distorts the true meaning of love when applied to God.

Argument 4: Divine Inaction and Suffering

- Premise 1: A compassionate being would intervene to prevent unnecessary suffering.

- Premise 2: The God depicted in the Bible allows suffering, including that of innocents, without intervening.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the God of the Bible does not act in a compassionate manner.

Argument 5: Logical Inconsistency in Divine Love

- Premise 1: The Bible claims that God is loving.

- Premise 2: The Bible also attributes actions to God that do not reflect love (e.g., causing suffering to innocents).

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Bible contains a logical inconsistency regarding the nature of divine love.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Innocent Suffering

CHRIS: The Bible teaches that God is infinitely loving and just, even if we don’t fully understand His actions. His ways are higher than ours, and sometimes what appears harsh to us is part of a greater purpose.

CLARUS: But if we define love by its effects, would a loving God really cause innocent suffering? Take the Flood, for instance—why would a God of love destroy innocent children along with the wicked?

CHRIS: The suffering of those children could have been a means of bringing them into Heaven sooner, sparing them from growing up in a sinful world. God’s perspective on suffering may be far different from ours.

CLARUS: That’s an attempt to justify suffering, but it doesn’t explain why a loving God would inflict it at all. If love inherently avoids harm to innocents, doesn’t claiming that God has a hidden reason for inflicting it undermine the very meaning of love?

CHRIS: Perhaps God allows suffering to emphasize His standards of justice and to show the consequences of disobedience. Without consequences, people might not understand the importance of living righteously.

CLARUS: But true justice should target the guilty, not the innocent. The Bible even says, “The son will not share the guilt of the father” (Ezekiel 18:20), yet God punishes children for their parents’ sins in the Flood and other events. How can we call that justice?

CHRIS: That’s a fair question. Maybe these children were somehow affected by their parents’ sins or would have continued in their ways. God’s wisdom may reveal connections that are invisible to us.

CLARUS: If love and justice can mean anything God does, then they lose any consistent meaning. By redefining love to include harming innocents, aren’t we effectively making it no different from hatred?

CHRIS: But God, as the ultimate authority, has the right to define love and justice as He sees fit. His understanding is perfect, and our human minds are limited.

CLARUS: That’s where faith fails to provide a satisfactory response. If we’re meant to trust in faith alone, we surrender our ability to reason and our understanding of what love and justice truly mean. Faith should not require accepting what contradicts our core sense of compassion.

CHRIS: It’s true that faith can be challenging. But it calls us to trust that God’s actions are ultimately for the good, even if they seem contradictory to our human values.

CLARUS: Yet, if faith requires us to accept the suspension of justice and compassion, it stops being a bridge to understanding and becomes a means to avoid reasoned answers. Shouldn’t we use reason to question whether the biblical depiction of divine love truly aligns with any coherent concept of love and justice?

◉ God’s order to kill infants

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Judge and the Innocent Family

Imagine a judge who seeks to establish justice in a community plagued by crime. To make an example, this judge condemns not only the criminals but also their innocent children, even the youngest infants. The community would likely see such an act as an extreme and unjust abuse of power, not as a reflection of true justice. If justice involves protecting the innocent and holding only the guilty accountable, how can we apply this concept to a deity who punishes innocents alongside the guilty?

Analogy 2: The Surgeon’s Unnecessary Harm

Consider a surgeon who intentionally causes pain or harm to a patient without necessity, claiming it will ultimately benefit the patient in some obscure way. Though the surgeon has the skills to perform a healing procedure without causing unnecessary pain, they choose not to. If love entails minimizing suffering when possible, then how could a loving deity, who has ultimate power, justify inflicting harm on innocents as depicted in various biblical narratives?

Analogy 3: The Teacher’s Redefined Terms

Imagine a teacher who redefines fairness as favoring certain students over others without explanation. When challenged, the teacher claims their authority as a teacher allows them to redefine fairness however they see fit, even if it includes what others would call unfairness. This redefinition undermines the very concept of fairness and would likely erode the students’ trust. Similarly, if love and justice are redefined to include causing harm to innocents, it could undermine the trustworthiness of these terms when applied to a deity. Can a God legitimately invert the definitions of love and fairness to nearly the opposite of how humans understand love and fairness?

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. God’s Ways Are Beyond Human Understanding

Many theologians argue that God’s ways are incomprehensible to human reasoning. This perspective emphasizes that divine justice and love may not align with human standards because God operates on a plane of infinite wisdom and has a broader view of reality. From this standpoint, actions that appear unloving or unjust to humans may be part of a greater divine purpose that we cannot fully understand.

2. Suffering as a Test of Faith and Obedience

Theologians often propose that suffering can serve as a means to test and refine faith. By enduring hardship, believers may develop a stronger reliance on God and a deeper spiritual understanding. From this view, God’s allowance of suffering, even among innocents, can be seen as a temporary difficulty leading to eternal rewards, refining character and reinforcing obedience.

3. Original Sin and the Consequence of a Fallen World

Another theological response involves the concept of original sin, where humanity’s fall introduced suffering and death into the world. The innocent may suffer due to the collective consequences of human sinfulness, rather than as individual punishment. In this framework, God is not seen as directly causing suffering but rather as allowing the natural consequences of a world impacted by sin.

4. Suffering as a Path to Heavenly Reward

The idea that innocent suffering leads to eternal rewards in Heaven is another common theological response. This argument holds that earthly suffering, though painful, is temporary and insignificant compared to the eternal bliss awaiting believers in the afterlife. Thus, even the suffering of innocents is part of a greater divine plan that ultimately benefits them by securing their place in Heaven.

5. Moral Frameworks for Divine Actions Are Inapplicable

Some theologians assert that God operates outside of human moral constraints. Divine actions cannot be evaluated by the same ethical standards we apply to humans because God, as the creator, has the authority to define goodness and justice. This argument suggests that our human perceptions of morality are limited, and any attempt to hold God accountable to them is flawed.

6. The Role of Free Will in a Fallen World

A theological view based on free will suggests that God allows suffering as a consequence of human choices, not as an arbitrary punishment. By granting humans freedom, God accepts the possibility of innocent suffering as part of maintaining moral agency. This position holds that a world with free will is more meaningful, even if it includes suffering, as it enables genuine love and relationship with God.

7. Biblical Accounts as Metaphorical Lessons

Lastly, some theologians interpret biblical stories involving divine actions as metaphors or allegories. Rather than historical accounts, these stories could serve as moral lessons or warnings about the seriousness of sin, encouraging readers to reflect on their actions and relationship with God. In this view, apparent instances of divine punishment are not literal but convey broader spiritual truths.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “God’s Ways Are Beyond Human Understanding”

If God’s ways are truly incomprehensible, then any claims about His love and justice lose their meaningfulness to us. To assert that God is loving while simultaneously saying we cannot understand His actions creates an incoherent concept of divine love—one that undermines itself by placing love beyond rational comprehension. Without a rational basis for understanding God’s morality, such claims cannot serve as meaningful explanations but instead ask for blind acceptance without clarity or consistency.

2. Response to “Suffering as a Test of Faith and Obedience”

Using suffering as a test, particularly involving innocents, raises issues related to the coherence of inflicting harm for loyalty or obedience. If God’s aim is to strengthen faith, there are countless ways to achieve this without causing harm to the innocent. Additionally, the idea of testing by suffering risks reducing faith to compliance under pressure rather than genuine conviction, suggesting a relationship built on fear rather than love.

3. Response to “Original Sin and the Consequence of a Fallen World”

While original sin might explain human fallibility, it does not justify the punishment of innocents for actions they did not commit. If justice involves individual accountability, then blaming or punishing descendants for ancestral sin contradicts that principle. This argument effectively removes agency from God’s justice, making innocent suffering seem arbitrary rather than an expression of a coherent logical framework.

4. Response to “Suffering as a Path to Heavenly Reward”

If innocent suffering is justified by a future Heavenly reward, it implies that suffering is an acceptable means to a positive end. However, a truly loving deity would logically achieve the same reward without requiring innocent pain, making the suffering unnecessary. Relying on future compensation for present suffering does not address the logical issue of a loving God inflicted harm in the first place, undermining the idea of a compassionate deity.

5. Response to “Moral Frameworks for Divine Actions Are Inapplicable”

If God operates outside human moral frameworks, then divine love and justice are effectively meaningless concepts to humans, as they would bear no resemblance to our understanding of those terms. Asserting that divine actions are exempt from logical coherence removes any basis for calling God “good” or “just.” This position essentially admits that God’s morality is arbitrary, failing to provide a rational explanation for why we should consider God’s actions as aligned with true justice or love.

6. Response to “The Role of Free Will in a Fallen World”

Allowing free will is not inherently incompatible with preventing innocent suffering. A loving and just deity would presumably structure a world where choices and consequences fall upon those who make them, not on uninvolved parties. If maintaining free will necessarily involves the suffering of innocents, then God’s design itself appears flawed, as it equates freedom with moral irresponsibility and contradicts the very purpose of a just world.

7. Response to “Biblical Accounts as Metaphorical Lessons”

If biblical stories are metaphorical, then the claim that these stories reflect God’s nature becomes unreliable. Metaphors that involve mass suffering or punishment of innocents convey problematic moral messages, regardless of their historical truth. Using metaphor to justify morally questionable actions in scripture undermines the argument for God’s inherent goodness, as it presents troubling lessons on love and justice that contradict the values expected of a moral deity. (Morality is not assumed in this reductio critique.)

Clarifications

The arguments presented operate on a reductio ad absurdum approach, where the theological claims about divine love and justice are tested for internal coherence. This method highlights logical inconsistencies within the theological framework, especially when divine actions conflict with human concepts of love and justice. Importantly, these critiques do not assume moral realism—they do not claim that objective moral truths exist independently of human interpretation. Instead, they focus on whether the theological definitions of love and justice are meaningful within the context provided by religious texts.

This critique aligns with moral anti-realism, where moral values are human constructs. The arguments explore if theological claims about divine morality can coherently align with these constructs, rather than asserting any absolute standard of right or wrong.

An Enhanced Explanation:

In everyday language, words rely on shared, commonly accepted definitions. When an individual attempts to redefine a term to something close to its inverse, it breaks any meaningful link to the established linguistic community. This can be demonstrated using symbolic logic, where an inverse-like redefinition leads to contradictions and thus a complete failure of mutual understanding.

Symbolic Logic Formulation

Let be a domain of discourse (e.g., all persons or entities). Let

be a term with a common definition

, representing some property or concept, such that:

If someone proposes a new definition that is close to the inverse of

, we can write:

Here “” indicates that

is nearly, though not necessarily perfectly, the negation of

. Once

replaces

in discourse, participants speaking under the original meaning and those speaking under the new meaning will be unable to communicate effectively.

Examples of Radical Redefinition

- Redefining “love”

Letrepresent “x loves y” in the conventional sense (e.g., x actively cares for y’s well-being).

The new definition might be:

This proposedis near the opposite of

.

Under this redefinition, saying “x loves y” would be nearly the negation of any normal usage of love. - Redefining “justice”

Letmean “x enacts justice on a,” traditionally implying that a’s punishment is proportional to a’s actual wrongdoing.

A new definition might be:

This clashes with the core notion of justice as typically understood. It is effectively the opposite of imposing a fair punishment on the actual offender.

Breakdown in Common Language

- Original Meaning

This says: the propertycaptures what the community means by the term

.

- Redefinition

- Contradiction and Confusion

For any, asserting

while the listener interprets

effectively causes a logical clash. They are using the same word but referencing fundamentally opposite concepts.

- Impossible Communication

Thus, the redefined term no longer corresponds to what the community recognizes, destroying any shared frame of discourse.

Conclusion

Redefining a word so that it becomes the inverse of its commonly accepted meaning obliterates the foundation of mutual understanding. Symbolically, if , then statements containing that term lose any chance of coherent interpretation, and no genuine communication is possible.

Christian Apologetics Group Responses

◉ These quotes are some of the most salient, representative quotes in response to this issue from a Facebook group called “Christian Apologetics.” This group of 70K+ members consist of quite civil and well-educated apologies, many of them, pastors, or ministers.

Not all of the responses were problematic. The list below contains only clearly flawed responses, posted here for educational purposes. The last check revealed that there were a total of 311 comments in the thread.

1. “Language exists to glorify God. You exist to love God.”

Begging the Question — It presupposes the existence and authority of God without argument, embedding the conclusion in the premise.

2. “There’s no such thing as an innocent person.”

No True Scotsman — Reframes “innocent” to exclude all counterexamples and preserve theological assumptions.

3. “You don’t have the right to challenge what God says.”

Appeal to Authority (Divine) — Assumes divine command trumps rational examination without justification.

4. “The world didn’t create itself, bud.”

Red Herring — Distracts from the debate about divine love by pivoting to cosmological origins.

5. “Postmodernism is a helluva drug.”

Ad Hominem (Poisoning the Well) — Attempts to discredit the opponent by attributing their views to a suspect ideology.

6. “This entire thread is a temper tantrum…”

Ad Hominem (Dismissive) — Attacks the speaker’s temperament instead of the content of the argument.

7. “You’re just critiquing a figment of your imagination. A strawman.”

Straw Man — Misrepresents the argument as being against an invented God rather than addressing the actual critique.

8. “Fix your fallacy first… this is another red herring.”

Projection — Accuses the opponent of fallacies without identifying or demonstrating them.

9. “You’re just here to be coddled.”

Ad Hominem (Motivational Fallacy) — Attributes the arguer’s stance to emotional fragility instead of addressing the argument.

10. “Phil’s definition of love becomes entirely a meaningless preference.”

Straw Man — Misrepresents a linguistic critique as mere personal preference to undermine its legitimacy.

11. “You’re not clarifying—you’re obfuscating.”

Loaded Language — Uses pejorative terms to characterize the argument without refutation.

12. “Are you appealing to the fallacy of popular opinion?”

False Accusation of Fallacy — Mislabels a linguistic point based on common usage as an appeal to popularity.

13. “It doesn’t take a syllogism to identify a fallacy.”

Dismissive Assertion — Avoids justification while claiming argumentative superiority.

14. “You think you’re smarter than God?”

Appeal to Authority (Omniscience) — Invalidates critique by invoking God’s presumed intellectual supremacy.

15. “Only God can judge God.”

Special Pleading — Exempts God from standards applied to every other agent without rationale.

16. “You’re trying to fit God in a human box.”

Category Error (Misapplied) — Suggests inapplicability of logical critique by placing divine actions outside all human categories.

17. “God’s ways are higher than our ways.”

Appeal to Mystery — Evades logical scrutiny by declaring divine actions unknowable.

18. “You can’t judge God by human standards.”

Special Pleading — Demands different criteria for God’s behavior, insulating it from criticism.

19. “You must submit before you can understand.”

Preemptive Obedience Fallacy — Demands belief before evaluation, reversing epistemic responsibility.

20. “You need the Spirit of God to understand love.”

Epistemic Closure — Insists on exclusive access to understanding, preventing outsider critique.

21. “If God does it, it’s by definition good.”

Circular Reasoning — Defines goodness through divine action, making it unfalsifiable and empty.

22. “That’s not love as you understand it; it’s divine love.”

Equivocation — Changes the meaning of the term “love” mid-discussion to escape contradiction.

23. “You wouldn’t question the sun for burning you.”

False Analogy — Equates a natural, non-agentic phenomenon with agency.

24. “You’re twisting Scripture to fit your logic.”

Anti-Reason Fallacy — Suggests that rational coherence is inferior to scriptural loyalty.

25. “You don’t get to redefine love. The Bible defines love.”

Appeal to Scripture as Final Authority — Treats a text as immune to linguistic scrutiny, halting discussion.

26. “If you understood the Bible, you wouldn’t ask that question.”

Dismissive Circularity — Invalidates inquiry by assuming ignorance of a presumed truth, thus shutting down critique.

27. “You can’t possibly understand without being born again.”

Gnostic Fallacy — Suggests that only insiders with secret/spiritual knowledge can grasp or evaluate the claim.

28. “You’re reading the Bible without the Spirit, so you’re blind to the truth.”

Genetic Fallacy — Disqualifies criticism based on the source (unbeliever), not the substance.

29. “You just want to sin without guilt.”

Motivational Fallacy / Ad Hominem — Attacks the opponent’s motives instead of engaging with their argument.

30. “You’re trying to score points, not seeking truth.”

Ad Hominem (Motivational) — Impugns the intention behind the argument rather than examining its logic.

31. “You’re arrogant to think you can judge God.”

Appeal to Humility (Misused) — Treats confidence in moral reasoning as inappropriate, regardless of argument strength.

32. “God’s justice is perfect even when it seems cruel.”

Appeal to Paradox — Accepts contradiction as virtue and refuses to resolve apparent moral incoherence.

33. “You have to believe first, then the answers make sense.”

Faith-Based Circularity — Assumes belief is required to understand, removing the possibility of rational testing.

34. “I’ll pray for you.”

Condescending Dismissal — Poses as compassionate while evading engagement and implying spiritual deficiency.

35. “You’re just trolling.”

Poisoning the Well — Discredits the speaker’s intent instead of their argument, making honest debate unlikely.

36. “Your AI is your cheerleader.”

Circumstantial Ad Hominem — Dismisses the argument based on the tool used to generate it, not its validity.

37. “You’re just critiquing a God you don’t believe in.”

Category Error (Reframed) — Misunderstands hypothetical critique as belief-based inconsistency.

38. “You’re just parroting atheist talking points.”

Genetic Fallacy / Ad Hominem — Rejects the argument based on its perceived origin, not its content.

39. “I educate my AI, you just use it for claps.”

False Superiority Fallacy — Claims epistemic superiority by insulting how the opponent employs their tools.

40. “You’re angry at a God you say doesn’t exist.”

Straw Man — Misrepresents critique of a concept or narrative as emotional contradiction.

41. “God doesn’t owe you an explanation.”

Appeal to Power — Substitutes authority for justification, dismissing the need for rational defense.

42. “You’re attacking a strawman god of your own making.”

Circular Denial — Rejects critique without analysis by redefining God to always be exempt from it.

43. “You’re blind to the truth because of sin.”

Ad Hominem (Spiritual Condition) — Invalidates the critic’s epistemic legitimacy by attempting to invoke moral deficiency.

44. “You’re not seeking answers; you’re seeking attention.”

Ad Hominem (Psychological Projection) — Assigns base motives without addressing the claim itself.

45. “God’s love looks nothing like human love. That’s why you don’t get it.”

Unfalsifiability — Makes the claim immune to refutation by redefining its terms to exclude comparison.

46. “You’re arguing from a secular worldview, which can’t ground anything.”

Question-Begging Epistemology — Presupposes the falsity of the secular framework without argument.

47. “God defines justice. You don’t.”

Divine Command Theory Circularity — Treats divine fiat as sufficient basis for logical coherence without independent standard.

48. “Even your logic comes from God.”

Totalizing Claim / Absorption Fallacy — Enfolds all possible epistemic tools into the theology to make contradiction impossible.

49. “Faith doesn’t require evidence—that’s the point.”

Epistemic Abdication — Celebrates belief without evidence, abandoning rational standards entirely.

50. “The clay doesn’t get to question the potter.”

Appeal to Analogy (Submissive Model) — Uses a flawed analogy to deflect logical scrutiny of divine actions.

Leave a comment