Consider the Following:

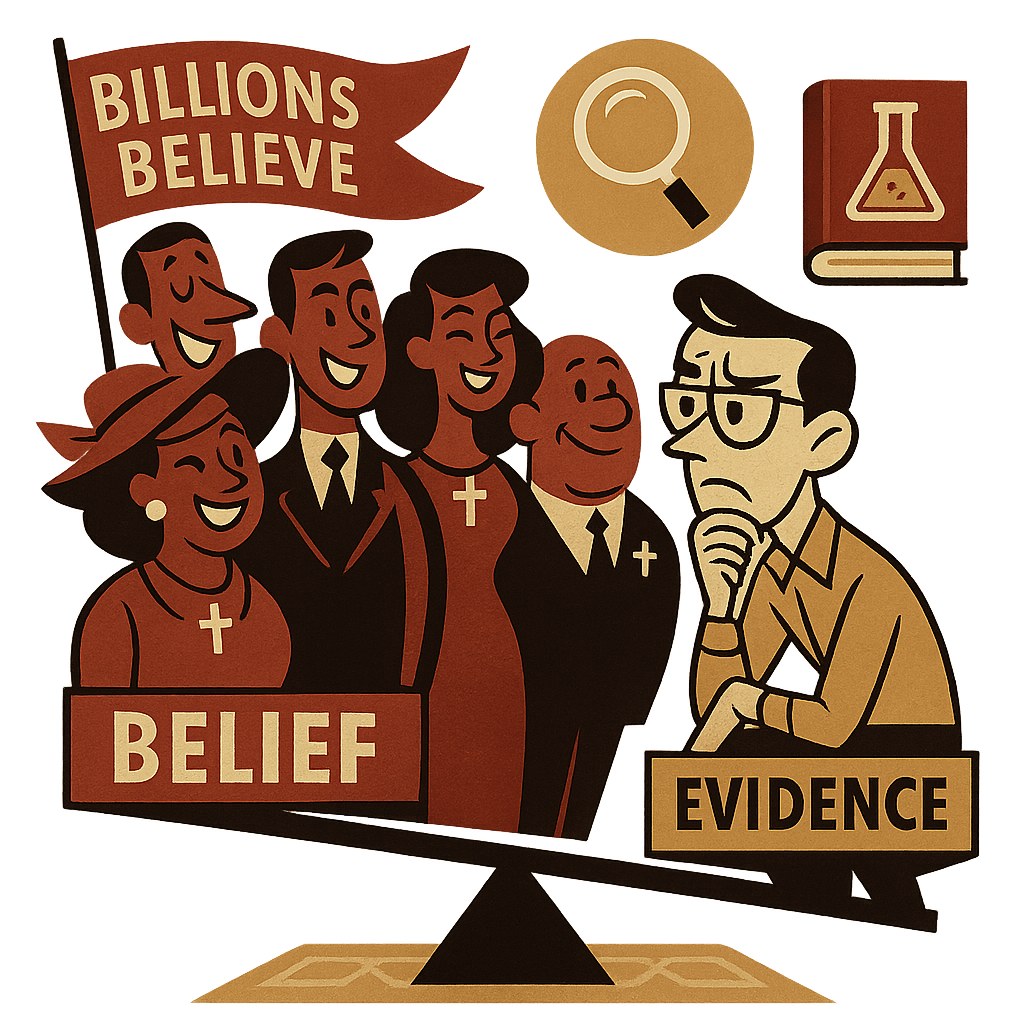

Summary: The belief of billions in any religion, including Christianity, does not equate to evidence of its truth, as collective conviction often results from cultural conditioning, emotional reinforcement, and a lack of objective scrutiny. True validity requires evidence-based standards that religious beliefs generally lack, leaving them unverified and uncorrected despite conflicting doctrines among world religions.

Imagine the experience of a Muslim child raised within a close-knit community of devout believers in Allah. From an early age, this child witnesses thousands around them—people they deeply trust—engaged in sincere worship, convinced of Allah’s existence. Given such conviction from trusted figures, the child could naturally think, “So many genuine people couldn’t possibly be wrong.”

However, for an outside observer, this widespread belief doesn’t equate to evidence of Allah’s existence. Now, apply the same reasoning to Christianity. Many Christians find comfort in their numbers, viewing the sheer size of the faithful as validation of Christian doctrine. But do numbers alone make a belief true?

This assumption that large groups validate religious truth is a logical fallacy. Here’s why collective belief fails as evidence:

1. The Flaw of Popularity in Determining Truth

Large numbers of people can believe in conflicting religions. Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism have billions of followers combined, yet each claims exclusive truths. For instance, Christians believe in the resurrection of Jesus, whereas Muslims believe Jesus was a prophet who wasn’t crucified. Both cannot be factually accurate. Thus, truth cannot hinge on numbers, or these contradictions would imply billions of people simultaneously hold false beliefs.

Even when truth-seeking communities form, as seen in science, mere agreement does not confirm absolute truth. However, science relies on falsifiable methods—testing, peer review, and evidence revision—which religion generally lacks. In science, consensus arises through objectivity, not popularity, as evidenced by the fact that scientific beliefs are updated or abandoned when proven wrong. Religious doctrines, by contrast, remain static despite conflicting beliefs or lack of empirical evidence.

2. Cultural Conditioning and Isolation Reinforce Beliefs Without Question

A child born in a religious household inherits not only the beliefs but the assumptions underpinning them. They’re encouraged to interpret the world within a cultural framework that discourages questioning. Religions often label non-believers as morally or spiritually flawed, as suggested in passages like Romans 1:18, reinforcing the notion that those outside the belief system are misguided.

Few believers truly examine their own faith with the critical perspective they might apply to others. This insularity means people rarely question the beliefs they grew up with, viewing their religion as “natural” and others as strange or misguided. Belief thrives on social reinforcement, leading to the perception that large numbers of believers lend authenticity. Yet, this approach isn’t evidence-based; it’s sociologically driven.

3. Psychological Effects of Religious Gatherings Create Illusions of Truth

The power of aesthetics and ritual in religious gatherings cannot be underestimated. Religious ceremonies, sermons, and music elicit deep emotional responses, often felt as spiritual confirmation. Psychology tells us that these experiences generate powerful feelings of unity and transcendence, which may be mistaken as divine presence.

In effect, religious rituals become self-reinforcing: the more profound the experience, the stronger the belief. However, emotions are unreliable indicators of truth. Just as a movie scene can bring us to tears without reflecting reality, a religious service can evoke intense emotions without validating the supernatural claims behind it. This emotional affirmation isn’t evidence; it’s psychological reinforcement.

4. Lack of Accountability to Evidence-Based Standards

Unlike scientific claims, which are tested and revised over time, religious claims remain unchanged despite contradictions or counter-evidence. Science has advanced by eliminating errors through testing and experimentation, leading to tangible successes in medicine, technology, and knowledge of the natural world. Religion offers no such self-correcting mechanisms, as doctrines are held as sacred rather than testable.

Religious beliefs are often justified through unverifiable promises (such as afterlife rewards) and reinterpreted explanations (like answered or unanswered prayers), insulating them from falsifiability. Religious leaders may offer interpretations for why certain prayers are “answered” or not, yet these explanations are immune to objective scrutiny. In the absence of evidence-based accountability, belief is encouraged to persist on faith, not facts.

Logical Argument: Do Large Numbers Validate Religious Belief?

Let’s structure the logic:

- P1: Over a billion people believe in Christianity.

- P2: Over a billion people believe in Islam.

- P3: Christianity and Islam present mutually exclusive claims about God and salvation.

- P4: Since both cannot be true, at least one billion people must be mistaken.

Conclusion: If billions of people can be wrong in one context, they can be wrong in another. Therefore, numbers do not validate a belief’s truth.

Key Takeaway

The size of a religious group does not confirm its beliefs’ validity. Collective conviction can foster a false sense of certainty without offering evidence-based assurance. True truth-seeking requires objective scrutiny, cultural awareness, and independence from emotional biases—elements that religions, relying on faith over fact, typically discourage.

Ultimately, the sincerity or number of believers in any religion is insufficient as proof of its truth, as demonstrated by the persistent conflicts and contradictions among world religions.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: The Flaw of Popularity in Determining Truth

- Premise 1: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and other religions have billions of followers who hold contradictory beliefs about God and salvation.

- Premise 2: Contradictory beliefs cannot all be true, as they assert mutually exclusive claims.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the size of a religious group does not validate its beliefs, as billions of people can hold false beliefs.

Argument 2: The Lack of Evidence-Based Standards in Religion

- Premise 1: Scientific claims are subjected to rigorous testing and revision, resulting in tangible advancements and the elimination of errors.

- Premise 2: Religious beliefs remain unchanged despite contradictions or a lack of empirical evidence and are often justified through unverifiable promises and reinterpreted explanations.

- Conclusion: Consequently, religious beliefs are not held to evidence-based standards, and their truth cannot be confirmed through objective scrutiny.

Argument 3: Cultural Conditioning Reinforces Religious Belief Without Question

- Premise 1: People raised within religious communities are often discouraged from questioning their beliefs, viewing them as “natural” due to cultural isolation.

- Premise 2: Exposure to only one belief system fosters a sense of authenticity that is psychologically reinforced by community and cultural ties rather than evidence.

- Conclusion: Therefore, cultural conditioning creates the perception of religious truth without validating it through objective measures.

Argument 4: Emotional Experiences in Religious Gatherings as False Indicators of Truth

- Premise 1: Religious gatherings often use music, rituals, and aesthetically powerful settings to evoke strong emotions in participants.

- Premise 2: Emotions, while profound, do not serve as reliable indicators of truth and can create an illusion of confirmation.

- Conclusion: Hence, emotional experiences in religious settings reinforce belief without providing objective evidence of its validity.

Argument 5: Logical Incompatibility of Conflicting Religious Beliefs

- Premise 1: Over a billion people believe in Christianity, and over a billion people believe in Islam, which present mutually exclusive claims about God and salvation.

- Premise 2: Since both religious systems cannot be true simultaneously, at least one billion people are necessarily mistaken in their beliefs.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the large number of believers in any given religion does not confirm the truth of their beliefs.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Reliability of Collective Belief in Establishing Religious Truth

CHRIS: I think the fact that billions of people believe in Christianity adds credibility to its truth. How could so many people, across generations, be wrong about the existence of the Christian God?

CLARUS: That’s an understandable perspective, Chris, but large numbers of believers don’t necessarily confirm a belief’s validity. Think about it: Islam also has over a billion followers who hold beliefs directly contradictory to Christian doctrines, especially regarding Jesus. Since both can’t be right, we know that large groups can indeed be mistaken.

CHRIS: But in science, when many experts converge on a conclusion, it’s usually a strong indicator of truth. Why wouldn’t the same apply to religion?

CLARUS: The difference lies in evidence-based standards. In science, consensus arises from objective testing and falsifiability—ideas are challenged, revised, and sometimes abandoned based on evidence. Religions, on the other hand, maintain their doctrines despite contradictions and lack the self-correcting mechanisms that science depends on. So, while scientific convergence can be reliable, religious consensus isn’t held to those same standards.

CHRIS: Still, isn’t it likely that the persistence of belief in Christianity across cultures and eras speaks to some underlying truth?

CLARUS: Not necessarily. Many people remain within the cultural framework they were raised in, rarely questioning the beliefs that feel natural to them. Most are simply taught to view their religion as “true” and others as misguided. Without stepping outside their own cultural and religious assumptions, they can’t see these beliefs critically.

CHRIS: I understand that point, but I’ve personally experienced the presence of God in worship. The emotional power of religious gatherings seems too profound to be mere coincidence or illusion.

CLARUS: Emotional intensity in religious settings is common and powerful, but emotions don’t equate to truth. Religious ceremonies and rituals are designed to evoke strong emotions, which can feel like divine confirmation but are actually psychological responses to music, community, and familiar ritual. Just because something feels real doesn’t mean it is objectively true.

CHRIS: So, you’re saying that despite the sincerity and size of the Christian community, these factors don’t prove the truth of Christian doctrine?

CLARUS: Exactly. Sincerity and numbers alone don’t validate beliefs—especially when large numbers of people across different religions hold incompatible beliefs. If we accepted large groups as evidence of truth, we’d be forced to conclude that billions of people simultaneously hold false beliefs in other religions. Therefore, while faith may feel meaningful, it doesn’t stand as evidence of objective truth.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

1. The Popularity of Ancient Beliefs

Consider that for centuries, vast numbers of people believed the Earth was flat and that the sun revolved around the Earth. Their collective conviction did not make these beliefs true; they were simply widely accepted because they aligned with what seemed intuitively correct to those societies. Popularity alone did not validate these beliefs, and it was only with objective evidence and scientific advancements that we corrected these misconceptions. Similarly, religious beliefs held by billions do not guarantee truth without the support of evidence-based standards.

2. Cultural Influence on Taste Preferences

Imagine a culture in which everyone believes a specific food is the most delicious in the world, despite people in other cultures finding it unpleasant. For them, the belief that it’s “the best” is based on cultural conditioning, not on any objective measure of taste. Their collective opinion doesn’t make the food objectively superior; it simply reflects their shared experience. Likewise, religious communities often hold their beliefs as true because of cultural isolation, not because these beliefs have been objectively validated.

3. Emotional Responses to Music as Indicators of Truth

Imagine a concert where the entire audience feels deeply moved by the music. The emotions are powerful, yet they don’t imply that the song’s lyrics represent any universal truth—they simply resonate personally with listeners. Similarly, in religious gatherings, the emotional experience can feel profound and validating, but these feelings do not serve as evidence of the beliefs behind them. Just as music evokes emotions without confirming truth, religious ceremonies can create intense feelings without validating religious doctrines.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. The Nature of Religious Truth

Theologians may argue that religious truth is distinct from scientific truth and doesn’t rely on empirical evidence alone. In Christianity, faith is a fundamental component, and believers would claim that divine revelation and spiritual experiences are legitimate ways of knowing God, offering a type of truth that transcends what science can measure or test. While science seeks objective facts, religion is concerned with ultimate meaning and moral guidance, which require a different approach to truth.

2. Diversity of Religious Experience as Evidence of a Higher Reality

Some theologians argue that the diversity of religious experiences worldwide actually supports the existence of a higher reality or divine source. They suggest that while different religions may interpret the divine differently, the shared experience of the transcendent across cultures points to a common spiritual dimension. This perspective maintains that even though beliefs differ, the underlying experience of the divine is universally significant and hints at an objective reality beyond human comprehension.

3. Role of Cultural and Emotional Influences in Divine Revelation

Theologians might accept that cultural conditioning and emotional experiences play roles in shaping one’s religious faith, but they would contend that these elements are part of how God reveals Himself to humanity. They argue that God’s presence can be felt through community, rituals, and shared worship, which use emotional engagement as a means for divine connection rather than as a source of illusion. Thus, religious gatherings don’t just evoke emotions; they provide a context for experiencing and responding to God’s presence.

4. The Transformative Impact of Faith as Evidence

Theologians may highlight that faith often has a transformative effect on individuals, leading them toward positive moral change, charity, and self-sacrifice. This effect, they argue, suggests that religious beliefs are not only psychologically powerful but also genuinely impactful in ways that go beyond naturalistic explanations. The argument here is that if faith in God consistently results in life-changing outcomes for billions, this impact is itself a kind of evidence of divine truth, as it produces results that align with God’s teachings.

5. God’s Ways Beyond Human Understanding

A common theological response is that God’s nature is beyond human comprehension, meaning that attempts to apply human logic or scientific standards to divine matters are inherently limited. Theologians argue that expecting religion to conform to the same standards as science misunderstands its purpose; faith requires humility and acceptance that some truths transcend human logic. From this view, the lack of empirical evidence is not a flaw but rather an invitation to trust in a higher reality that humans are not fully equipped to understand.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to the Claim of Distinct Religious Truth

While religious truth might be understood as distinct from scientific truth, this distinction does not excuse the lack of evidence supporting its claims. In fact, if religious truths are to inform or dictate moral guidance and ultimate meaning for billions, they should be even more rigorously scrutinized. Accepting truths solely based on faith can be problematic, as it permits any belief to stand unchallenged. When religious truth makes factual assertions about reality—such as the existence of God or life after death—these should meet evidence-based standards to hold credibility beyond mere conviction.

2. Response to the Argument of Shared Religious Experience as Evidence

The existence of shared religious experiences across cultures does not necessarily point to a single higher reality. Psychology and anthropology offer natural explanations for why humans across cultures seek transcendent experiences and create shared rituals. Similar psychological mechanisms can lead to diverse interpretations without implying an actual divine source. Additionally, the incompatibility of different religious doctrines undermines the idea of a universal spiritual truth; rather, these experiences may simply reflect common human cognitive and social patterns.

3. Response to Cultural and Emotional Influences as Divine Revelation

If God’s presence is revealed through cultural and emotional experiences, then it becomes difficult to distinguish between genuine divine contact and psychological reinforcement. Many non-religious gatherings—such as concerts or sports events—also evoke powerful emotions and a sense of unity, yet no divine presence is claimed. Without objective means to separate divine experiences from emotional responses, it remains speculative to attribute these feelings specifically to God. If emotional aesthetic engagement is all that’s needed, then any deeply felt conviction could be mistaken for divine revelation, diluting the credibility of such claims.

4. Response to the Transformative Impact of Faith

The transformative impact of faith can be explained without invoking divine truth. People have been deeply changed by ideologies, philosophies, and secular practices that promote self-discipline and community values. Positive change is not exclusive to religious faith; rather, it reflects the motivational power of commitment to a cause or belief system. A naturalistic explanation suggests that people’s moral transformation stems from the communal reinforcement of values, not necessarily from the truth of the religious doctrine itself. Thus, the outcomes of faith do not prove its divine origin any more than similar effects in non-religious contexts validate their beliefs as ultimate truths.

5. Response to God’s Ways Being Beyond Human Understanding

The claim that God’s nature is beyond human comprehension creates an untestable and unfalsifiable proposition, effectively placing religious beliefs outside of rational inquiry. This move not only shields religion from evidence-based challenges but also raises questions about the coherence of such beliefs. If God’s ways are truly incomprehensible, then religious doctrines derived from human understanding cannot reliably represent God’s will. Using incomprehensibility to justify a lack of evidence undermines the reliability of religious teachings, as it renders any claim about God equally valid or invalid without an objective basis for discernment.

Clarifications

Here are arguments that some Christians might use to argue that the billions of Muslims do not validate the truth of Islam, along with notes on how these arguments can be equally applied to Christianity and its billions of believers:

1. Different Cultural Foundations

Christians might argue that Islamic beliefs are heavily influenced by cultural and regional factors, which shape religious adherence rather than objective truth. They might suggest that Muslims often remain within their faith due to the cultural framework they were raised in rather than independent conviction.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: Many Christians also inherit their beliefs within predominantly Christian cultures. Thus, the cultural foundations argument could imply that both Christianity and Islam may be held due to cultural conditioning rather than objective truth.

2. Emphasis on Emotional and Communal Experience

Christians might claim that Islamic gatherings and rituals create powerful emotional experiences that reinforce belief but don’t confirm Islam’s truth. They may argue that such experiences are psychological rather than divine.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: Many Christian gatherings also create strong emotions through rituals, music, and community, which could similarly be seen as psychological reinforcement rather than evidence of divine truth.

3. Contradictory Doctrines

Christians often point to doctrinal contradictions between Islam and Christianity—for instance, Islam’s rejection of Jesus as divine—as evidence that Islam cannot be true, despite the large number of Muslims. They argue that if one religion’s beliefs are factually incorrect, then size alone cannot validate its truth.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: Since Christianity and Islam make mutually exclusive claims, it’s possible that billions of Christians are also mistaken in their beliefs. Therefore, numbers alone do not validate the truth of either religion.

4. Lack of Evidence-Based Standards

Some Christians argue that Islam, like other religions, does not hold its beliefs to evidence-based standards and relies on faith rather than empirical proof. They may claim that faith alone is insufficient to establish truth.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: Christianity, too, relies heavily on faith and lacks falsifiable evidence for many of its core beliefs. Thus, an argument against Islam for lacking evidence-based standards would also apply to Christianity.

5. Moral and Theological Criticisms

Christians might argue that certain moral teachings or theological doctrines in Islam seem to conflict with what they consider rational or moral, suggesting that this undermines Islam’s claim to truth, regardless of its billions of adherents.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: People can similarly critique aspects of Christian moral teachings or doctrinal claims, especially where they conflict with contemporary ethical views. If moral criticisms against Islam weaken its validity, the same could apply to Christianity’s doctrines and practices.

6. Divergent Interpretations Within Islam

Christians may point to sectarian divisions within Islam, such as Sunni and Shia differences, to argue that internal conflicts undermine its truth claims. They may say that these divergent beliefs show a lack of unity and clarity, casting doubt on Islam’s validity.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: Christianity itself has numerous denominations—Catholicism, Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and countless sects within each branch—suggesting internal conflicts about interpretation and doctrine. This division could similarly suggest that Christianity’s size does not reflect a unified truth.

7. Historical Spread by Socio-Political Means

Some Christians argue that the historical spread of Islam was often tied to political and military expansion, which influenced its wide adoption but does not confirm its truth.

- Equally Applied to Christianity: The spread of Christianity also involved political and social factors, including colonization and state endorsement. Thus, attributing Islam’s growth to socio-political expansion could equally challenge Christianity’s spread as evidence of truth.

Leave a comment