Consider the Following:

Summary: Rational belief requires that confidence in a claim aligns proportionately with the weight of supporting evidence, adapting as evidence changes. In contrast, the Bible often promotes a binary approach to belief—either unwavering faith or none at all—which can conflict with the evidence-responsive nature of rational thinking.

In the framework of rational belief, the strength of one’s conviction should reflect the degree of supporting evidence. This approach is evidence-responsive, suggesting that belief ought to adjust dynamically with new information. However, in contrast, the Bible often promotes a binary conception of belief: you either believe, or you don’t. This binary stance starkly contrasts with the nuanced, evidence-proportionate approach of rational thinking, where belief strength is seen as a continuum directly influenced by evidence.

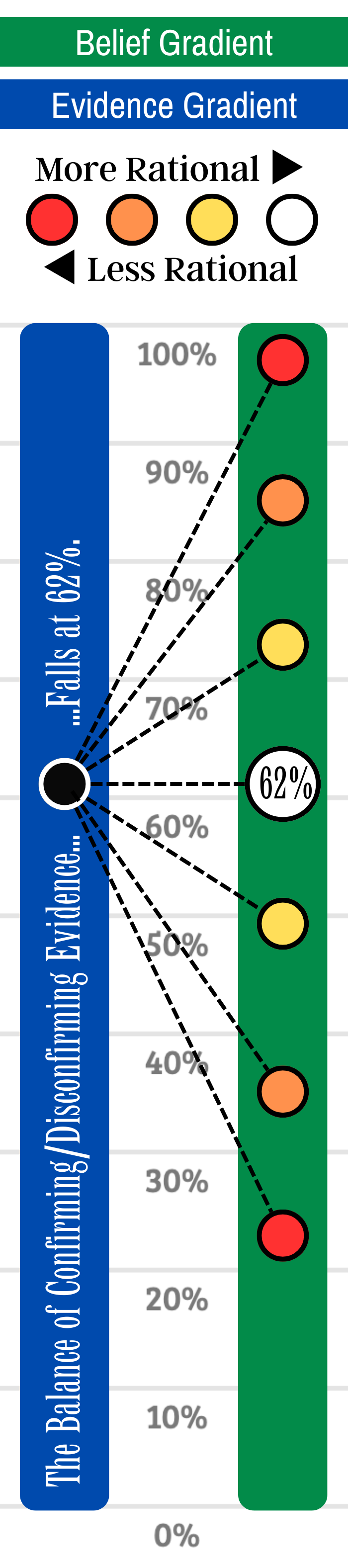

The Belief Gradient vs. Evidence Gradient: A Rational Perspective

Rational belief relies on two gradients:

- Belief Gradient – This reflects the strength or confidence one has in a claim.

- Evidence Gradient – This gradient represents the cumulative balance of evidence, both confirming and disconfirming.

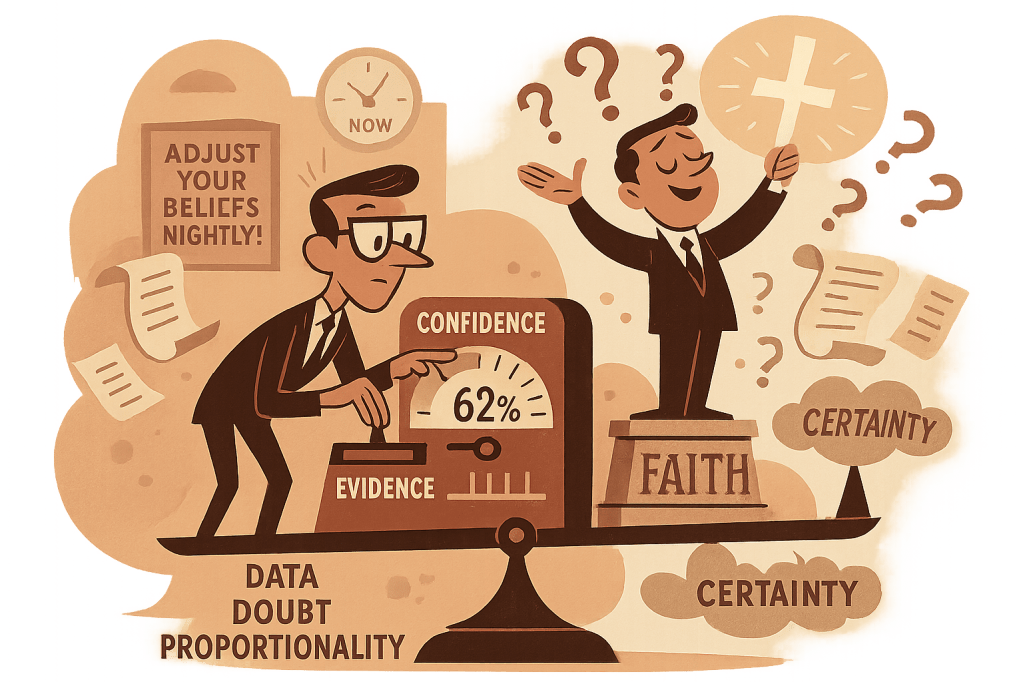

In rational thinking, these gradients should be aligned: if evidence for a claim stands at, say, 62%, then belief should match that level of confidence. Rationality requires belief to mirror evidence, neither inflating confidence beyond what is warranted nor ignoring contrary data. In the biblical perspective, however, belief isn’t graded by evidence but is presented as an all-or-nothing proposition—one either has faith, or one lacks it. This binary approach does not accommodate the spectrum of confidence that evidence-based belief demands.

Examples of Irrational Belief

- Health Treatments: A person may strongly believe in the effectiveness of a dubious alternative medicine despite minimal scientific evidence, driven by an intense hope for a cure or relief from symptoms.

- Investment Decisions: An investor might have high confidence in a speculative stock despite limited data or poor financial indicators, fueled by the hope of a large return, disregarding the actual risks involved.

- Conspiracy Theories: An individual may hold an unwavering belief in a conspiracy theory despite significant evidence debunking it, due to a deep-seated skepticism toward mainstream sources or authority figures.

- Relationship Expectations: Someone might believe their partner will change problematic behaviors despite repeated evidence to the contrary, out of an irrational hope to avoid the reality of a breakup.

- Apocalyptic Predictions: A person may believe that an apocalyptic event is imminent based on anecdotal or ambiguous signs, maintaining this belief even as past predictions fail, driven by a heightened skepticism toward counter-evidence and a desire to feel “in the know.”

Evidence-Proportionate Belief vs. Biblical Certainty

Rational belief holds that each belief should correlate with the weight of evidence available. The rational thinker must be willing to shift their belief as new evidence emerges, ensuring that beliefs remain proportionate to the balance of confirming and disconfirming information. In contrast, biblical faith often implies unwavering certainty that does not fluctuate with shifts in evidence. Biblical faith is depicted as an absolute conviction, a commitment to a belief in God or doctrine that is not to be swayed by external validation or evidence. This approach essentially promotes epistemic rigidity—a stance that prioritizes a fixed, binary belief over dynamic, evidence-responsive reasoning.

The Problem of Static, Binary Belief

A static belief, which remains unchanged regardless of shifts in evidence, is inherently irrational from a rational perspective. Biblical teachings, however, often encourage believers to hold their faith unwaveringly, treating doubt as a sign of weakness or even moral failure. This binary approach discourages the fluidity of belief essential to rational inquiry. In rational thought, beliefs should adapt according to the balance of confirmation and disconfirmation. A belief that remains unmoved by evidence isn’t just irrational; it reflects dogmatism and a reluctance to engage with reality in a meaningful, evidence-based way.

Rational Belief as Evidence-Responsive vs. Biblical Faith as Binary

In rational belief systems, confidence is proportionate to evidence:

- Updating Beliefs: Rational thinkers adjust their beliefs as new evidence emerges, constantly refining their beliefs to match the evidence gradient.

- Moderating Confidence: Confidence is tempered to reflect the evidence, avoiding the pitfalls of overconfidence or blind faith.

- Bias Reduction: Beliefs are held accountable to evidence alone, minimizing the influence of biases and personal inclinations.

However, biblical faith encourages a binary commitment where belief does not adjust based on evidence. Instead, believers are often urged to hold a steadfast faith, suggesting that evidence—whether supporting or opposing—is secondary to the act of belief itself. In the biblical paradigm, doubt and questioning are frequently seen as spiritual failings rather than essential components of rational inquiry. This contrasts sharply with the epistemic humility and intellectual openness found in evidence-responsive belief systems.

The article linked to above discusses survey findings on differing beliefs about the degree of faith necessary for redemption, highlighting a notable divide between those who see redemptive faith as requiring absolute certainty and those who accept a high but not complete level of faith. It also explores the biblical context of the “faith of a mustard seed” and the surprising survey results that suggest confusion among Christian leaders about faith’s role in salvation.

Biblical Binary Belief: A Barrier to Rational Thinking

The binary nature of biblical faith discourages believers from engaging in the responsive adjustment of belief that is central to rationality. When belief is treated as an absolute—either you believe or you don’t—there is little room for intellectual flexibility or for beliefs to evolve with new evidence. This binary approach can lead to confirmation bias, where one only seeks evidence that supports pre-existing beliefs and dismisses anything that contradicts them. In contrast, a rational approach encourages believers to recalibrate their belief in response to evidence, keeping belief and evidence in dynamic alignment.

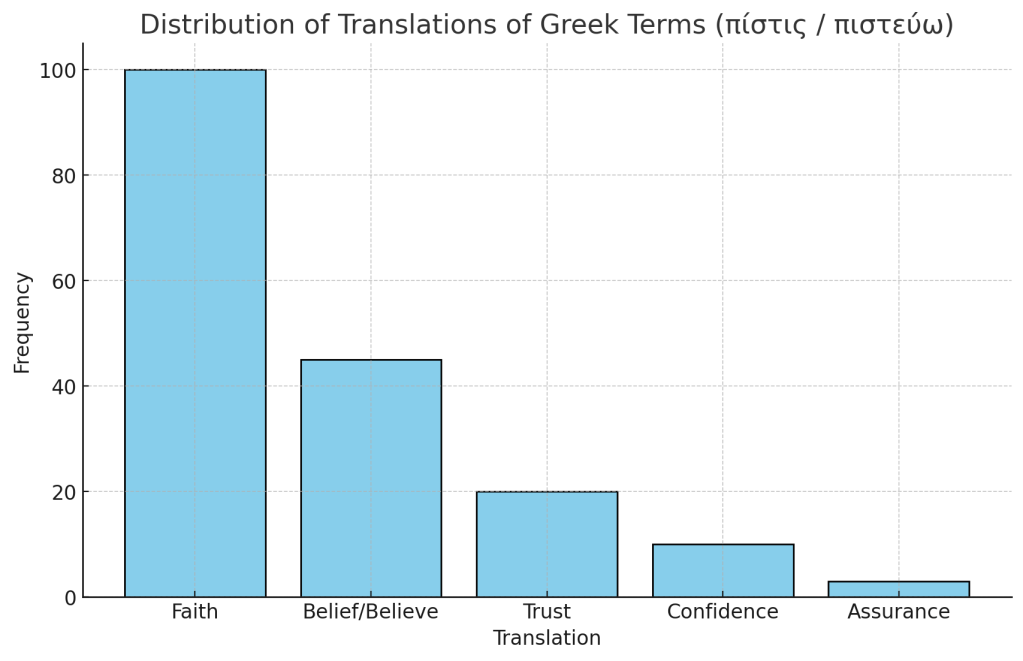

The article linked to above provides an in-depth analysis of each New Testament verse containing the Greek terms for “faith” (πίστις) and “to believe” (πιστεύω), scoring them based on whether they encourage evidence-based belief. It concludes that biblical faith is generally depicted as trust in divine authority rather than a response to empirical evidence, emphasizing relational or moral belief over rational evaluation.

Rational Belief as Epistemic Responsibility

In rational thinking, belief is a continuum, not a binary. This continuum allows for beliefs that are tentative, moderately confident, or near certain, all depending on the strength of the evidence. The evidence-proportionate approach to belief respects both the integrity of truth and the limits of current knowledge. In contrast, biblical belief emphasizes absolute commitment rather than proportional confidence. The binary model of belief leaves little room for doubt, adaptation, or the nuanced engagement with evidence that rational thinking requires.

This difference highlights the tension between the rational model and the all-or-nothing model of biblical faith:

- Rational belief is a commitment to intellectual humility, where belief adapts to evidence.

- Biblical belief is a commitment to faith, often depicted as unchanging regardless of evidence.

Conclusion: Rational Belief Demands Evidence Alignment, Not Binary Faith

Rational belief is an ethical responsibility that demands belief be proportional to evidence. This evidence-responsive approach fosters intellectual integrity, where beliefs are shaped by reality rather than by a static, binary commitment. Rational thinkers recognize that belief is not about unwavering conviction but about maintaining a dynamic balance with evidence.

The Bible, however, often frames belief as a binary—an unyielding “yes” or “no” position. This approach can be seen as inherently opposed to evidence-proportionate belief. Rationality calls for flexibility, where belief is continuously adjusted based on the weight of evidence. In contrast, the biblical model prioritizes an immovable faith that resists evidence-based adaptation, suggesting that belief, to be valid, must be unconditionally held.

In the end, rational belief aligns with evidence, while biblical belief aligns with commitment, often at the expense of responsiveness to reality. Rational belief embodies epistemic humility, while binary faith can lead to epistemic rigidity. Rationality seeks truth through evidence; binary belief seeks conviction despite evidence. The former is a pathway to truth-seeking; the latter, a pathway to certainty-seeking detached from the evolving landscape of evidence.

The article linked to above argues that faith, traditionally understood as belief exceeding available evidence, is intrinsically irrational. It critiques the defenses of faith that attempt to normalize it by claiming faith is unavoidable or that many are unaware of their faith-based beliefs, showing that such defenses create semantic confusion to shield faith from rational criticism.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Rational Belief Requires Evidence-Proportionate Confidence

- Premise 1: Rational belief is a belief that aligns its degree of confidence with the strength of the evidence supporting it.

- Premise 2: If a belief is held with a degree of confidence that does not match the degree of evidence, then it is irrational.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a belief can only be rational if its confidence level is proportionate to the evidence available.

Argument 2: Static Belief is Irrational

- Premise 1: A static belief is a belief that remains unchanged, regardless of any new or contrary evidence.

- Premise 2: Rational belief requires the adjustment of confidence in response to new evidence or changes in the balance of supporting and disconfirming evidence.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a static belief is inherently irrational because it fails to respond to evidence.

Argument 3: Biblical Faith Promotes Binary Belief

- Premise 1: The Bible often presents belief as a binary choice: one either has faith or one does not, with little or no emphasis on adjusting belief according to evidence.

- Premise 2: Rational belief, in contrast, is a continuum that aligns with the degree of evidence and changes with new information.

- Conclusion: Therefore, biblical faith promotes a binary belief model that is inconsistent with rational, evidence-responsive belief.

Argument 4: Epistemic Rigidity Undermines Rational Belief

- Premise 1: Epistemic rigidity occurs when an individual maintains a belief with absolute certainty, even when contrary evidence arises.

- Premise 2: Rational belief requires epistemic flexibility, or the ability to modify one’s confidence level as the evidence landscape changes.

- Conclusion: Therefore, epistemic rigidity undermines rational belief because it prevents alignment with changing evidence.

Argument 5: Evidence-Resistant Beliefs Lead to Bias and Dogmatism

- Premise 1: Beliefs that are evidence-resistant—unresponsive to contrary evidence—are often influenced by confirmation bias and social validation rather than objective evaluation.

- Premise 2: Rational belief requires an openness to disconfirming evidence and a commitment to align belief with the evidence, reducing bias.

- Conclusion: Therefore, evidence-resistant beliefs lead to bias and dogmatism, undermining the objectivity needed for rational belief.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Rational Belief vs. Biblical Faith

CHRIS: Why do you think rational belief and faith are in conflict? Isn’t faith simply a form of belief?

CLARUS: Faith and rational belief serve different functions. Rational belief aligns its confidence level with the strength of the evidence, adjusting as evidence changes. Faith, especially in a biblical sense, often operates as a binary commitment: you either believe fully, or you don’t, regardless of evidence.

CHRIS: But faith isn’t supposed to be unstable or always shifting. It’s meant to be steadfast and unchanging. Isn’t it better to have certainty?

CLARUS: That steadfastness is exactly the issue for a rational framework. Rational belief thrives on what we call epistemic flexibility—the willingness to modify belief strength as the evidence landscape changes. A static belief, by nature, cannot be rational, because it doesn’t respond to new or contrary evidence.

CHRIS: But wouldn’t constantly shifting beliefs show weakness or indecisiveness? Faith is about holding strong to what we know in our hearts to be true.

CLARUS: The strength you’re describing sounds like epistemic rigidity, a refusal to adjust belief in light of new evidence. In rational thought, that rigidity opens the door to confirmation bias, where beliefs are supported not by evidence but by a selective focus on what confirms them. Rational belief requires openness to disconfirming evidence—it’s not about weak conviction; it’s about a commitment to truth, not simply certainty.

CHRIS: So you’re saying that rationality always needs to see proof? But isn’t that restrictive? Some things, like faith, go beyond what we can see.

CLARUS: That’s one way to look at it, but rational belief isn’t about demanding absolute proof; it’s about holding a degree of confidence that matches the evidence. For example, if I have 62% confidence in a claim, that confidence should reflect the supporting evidence without exceeding it. By contrast, biblical faith often calls for absolute certainty regardless of the evidence balance, which creates a disconnect between belief and reality.

CHRIS: But faith is about trust, not constantly questioning. Isn’t there value in believing without requiring evidence?

CLARUS: Trust has value, but in rational terms, belief should be evidence-proportionate. Belief without evidence is prone to dogmatism, where we cling to an idea as absolute truth without the willingness to let new data challenge it. This can lead to epistemic stagnation, which prevents intellectual growth and openness to truth-seeking.

CHRIS: But the Bible teaches a kind of faith that doesn’t rely on evidence. Isn’t that a strength?

CLARUS: From a rational perspective, that’s actually a weakness. When belief is binary—an all-or-nothing acceptance—it resists the evidence-responsive alignment that makes belief rational. If a belief stays static, even when strong disconfirming evidence arises, it becomes irrational. True strength in rationality is not in unwavering certainty but in epistemic humility—the recognition that beliefs need to align with what is most likely true based on available evidence.

CHRIS: So you’re saying biblical faith leads to dogmatism?

CLARUS: I’m saying that, without evidence proportionate belief, faith can lead to epistemic rigidity and confirmation bias. By setting belief as binary, biblical faith discourages the kind of intellectual flexibility essential to adjusting one’s stance with the changing balance of evidence. In a rational framework, aligning belief strength with evidence not only respects truth but also avoids the pitfalls of belief based solely on personal conviction.

CHRIS: I see your point about evidence, but isn’t there still value in a belief that transcends evidence?

CLARUS: The value, from a rational perspective, lies in epistemic responsibility—keeping beliefs in dynamic alignment with evidence. While belief beyond evidence might offer personal comfort, it runs the risk of detaching from reality. Rational belief is less about transcending evidence and more about reflecting it accurately to maintain intellectual integrity.

✓ Rational Belief Survey

Rational Belief Survey

Instructions: For each statement, rate your level of agreement on a scale from 1 to 5.

Scale:

- 1 = Strongly Disagree

- 2 = Disagree

- 3 = Neutral

- 4 = Agree

- 5 = Strongly Agree

Section 1: Evidence-Based Belief

- I adjust my confidence in a belief if new evidence emerges, even if it contradicts my current viewpoint.

- I am willing to lower my confidence in a belief if the evidence supporting it is weak.

- I am open to changing my beliefs if presented with strong disconfirming evidence.

- When I hold a belief, I actively seek out information that challenges it as well as information that supports it.

- I consider the reliability and credibility of sources before fully committing to a belief.

Section 2: Bias Awareness and Control

- I recognize that personal preferences or emotions can sometimes influence my beliefs and try to minimize their impact.

- I actively try to identify and correct any biases that might distort my understanding of the evidence.

- I avoid relying solely on group consensus or social validation to strengthen my beliefs.

- I am cautious about overconfidence and regularly question whether my belief strength accurately reflects the evidence.

- I recognize that believing something very strongly doesn’t make it true if the evidence doesn’t support it.

Section 3: Intellectual Flexibility and Skepticism

- I maintain a skeptical stance until there is sufficient evidence to warrant a high level of belief.

- I accept that I may be wrong, even about beliefs that feel intuitively or emotionally “right” to me.

- I value being accurate over being certain, and am willing to hold tentative or partial beliefs.

- I am open to adjusting my belief strength as new, relevant evidence becomes available.

- I avoid treating belief as binary (either absolutely true or false) and instead view it as a matter of degrees.

Scoring Rubric

For each statement, score the response as follows:

- 1 point for responses rated 1 (Strongly Disagree)

- 2 points for responses rated 2 (Disagree)

- 3 points for responses rated 3 (Neutral)

- 4 points for responses rated 4 (Agree)

- 5 points for responses rated 5 (Strongly Agree)

Score Interpretation

0-14 points: Low Evidence Alignment

Your beliefs show minimal alignment with evidence, and you may frequently hold fixed, rigid beliefs. Working on openness to new information, managing biases, and moderating confidence levels based on evidence could help move toward a rational degree of belief.

60-75 points: Highly Evidence-Aligned

You demonstrate a strong commitment to aligning your beliefs with the degree of evidence, practicing a high level of intellectual flexibility, skepticism, and bias awareness. You are likely to hold beliefs that accurately reflect available evidence and adjust beliefs as new information arises.

45-59 points: Moderately Evidence-Aligned

You generally aim to align beliefs with evidence, but there may be instances where biases or emotional influences affect your stance. Improving awareness of personal biases and increasing openness to disconfirming evidence could enhance your rational alignment.

30-44 points: Somewhat Evidence-Aligned

Your beliefs show some alignment with evidence, but emotional factors or social validation may occasionally skew your degree of belief. Developing habits of seeking counter-evidence and reducing overconfidence could help strengthen your evidence-based reasoning.

15-29 points: Limited Evidence Alignment

You may often hold beliefs that do not correspond with the evidence, likely due to emotional or social influences. Increasing self-reflection on biases and actively adjusting beliefs in response to evidence could improve rationality in belief formation.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

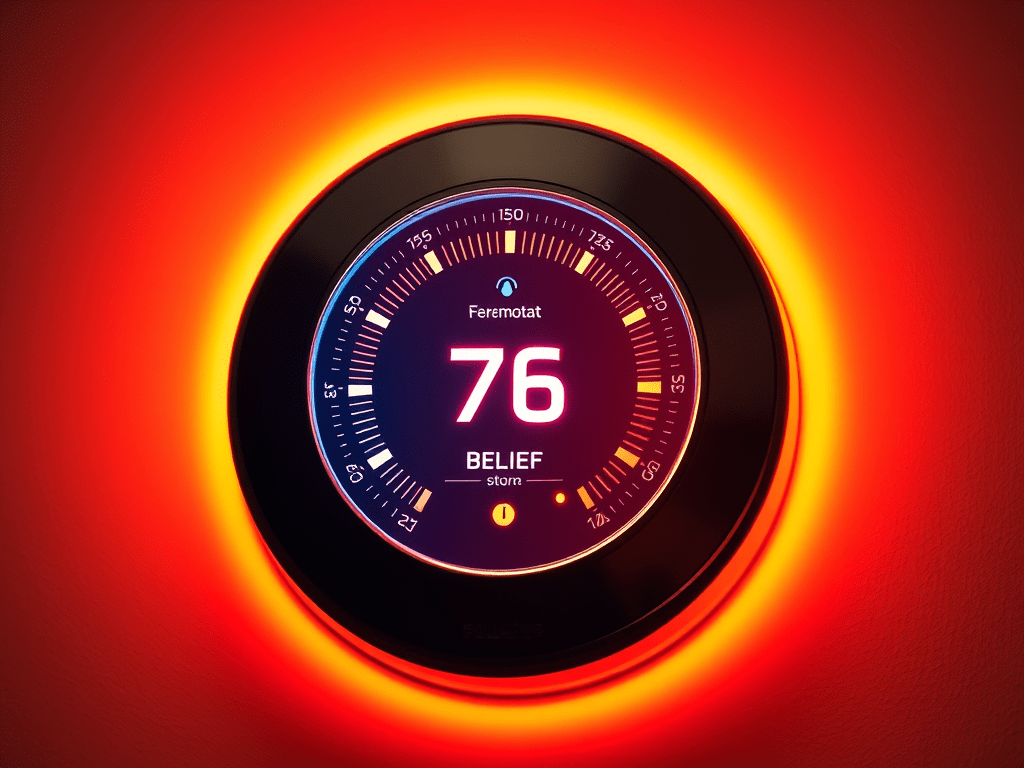

Analogy 1: The Thermostat of Belief

Imagine your belief as a thermostat that adjusts the temperature according to the evidence available, just as a thermostat adapts to changes in ambient temperature. If the evidence supporting a claim is at 76% certainty, your belief should reflect this level, setting at 76 degrees. However, a binary faith model acts like a thermostat stuck at full heat or completely off, disregarding any nuances or fluctuations in the environment. Just as a thermostat becomes ineffective if it cannot adjust to temperature changes, a static belief becomes irrational if it cannot adapt to new evidence.

Analogy 2: Navigating with a Compass vs. a Fixed Arrow

In rational thinking, belief acts like a compass needle, constantly adjusting its direction in response to new evidence, like shifts in the magnetic field. This allows you to stay oriented toward the truth. Conversely, binary belief is like navigating with an arrow fixed in one direction, regardless of where evidence points. While the compass maintains epistemic flexibility and adjusts with new information, the fixed arrow leads to a rigid, unyielding path, ignoring important updates along the journey. Rational belief requires that we recalibrate our bearings based on evidence rather than sticking to a preset route.

Analogy 3: Calibrating Scales for Accurate Weight vs. Fixing the Measurement

Consider a scale calibrated to measure weight precisely, with each reading directly reflecting the weight it measures, just as a rational belief reflects the evidence. If evidence supporting a belief increases or decreases, a rational approach adjusts the strength of belief to match. However, binary faith is like a scale fixed to always show “100 lbs” regardless of the actual weight. This inflexibility ignores the true measurement and replaces it with a static number. Just as a fixed scale gives inaccurate readings, static belief gives a distorted view of reality, failing to represent the actual balance of evidence.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Faith as a Different Kind of Knowledge

Some theologians argue that faith represents a form of knowledge distinct from empirical evidence. While rational belief aligns with observable evidence, faith is seen as knowledge of spiritual truths that go beyond what can be measured or proven in the physical realm. In this view, faith operates in a different epistemic domain and fulfills a purpose that empirical evidence cannot, guiding believers in matters of meaning and moral truth.

2. Faith and Certainty as Anchors in an Uncertain World

Theologians might also claim that the certainty of faith provides stability in a world where evidence can be ambiguous or incomplete. This stability offers psychological and spiritual benefits, allowing believers to maintain hope and purpose even when circumstances challenge logical understanding. According to this view, epistemic flexibility is less valuable in contexts of deep, existential belief, where unchanging faith can serve as an anchor.

3. Faith as a Rational Trust in Divine Authority

Some theologians argue that faith is not blind but rather a rational trust in the authority and reliability of God. Just as one might trust an expert on a topic they cannot personally verify, faith entails trusting God’s knowledge and authority on matters beyond human understanding. In this framework, faith is not about disregarding evidence but about placing trust in a divine source viewed as inherently reliable.

4. Evidence Alone is Insufficient for True Belief

Theologians may argue that evidence can point toward truth but does not necessarily compel genuine belief or commitment. True belief, in this view, requires a personal leap of faith that goes beyond mere evidence, engaging the believer’s heart and will. According to this perspective, rational belief based solely on evidence lacks the depth of conviction that faith fosters.

5. Faith as Transformative Knowledge

Theologians often view faith as a transformative experience that changes one’s character and outlook, which goes beyond what can be accomplished by evidence alone. In this view, rational belief lacks the power to deeply alter a person’s life, while faith invites a relationship with the divine that impacts a believer’s entire way of being. Therefore, faith is not primarily about evidence alignment but about spiritual transformation.

Counter-Responses

1. Faith as a Different Kind of Knowledge

From a rational perspective, defining faith as a “different kind of knowledge” introduces epistemic ambiguity and risks bypassing the need for justification. Knowledge traditionally implies a justified belief rooted in evidence or logic. If faith operates outside these bounds, it cannot meet the standards of knowledge applied to other beliefs. While spiritual truths may feel compelling, they should be held proportionate to the evidence supporting them; otherwise, they risk dogmatism rather than epistemic integrity.

2. Faith and Certainty as Anchors in an Uncertain World

While the stability of faith may offer psychological comfort, rational belief suggests that comfort should not outweigh truth alignment. Anchoring belief in certainty without evidence can lead to confirmation bias and resist reality. Rational belief advocates for epistemic humility, recognizing that unwavering certainty can obscure genuine understanding, particularly in a world where evidence and knowledge are constantly evolving. True stability in a rational framework is grounded in a commitment to seek truth rather than unwavering adherence to belief.

3. Faith as a Rational Trust in Divine Authority

Trusting in divine authority without proportionate evidence differs fundamentally from trusting an expert, as expertise is typically verified through transparent, observable evidence. In rational terms, belief in divine authority should similarly be evidence-responsive. Without demonstrable credentials or reliability, treating faith as trust in divine authority assumes what it seeks to prove, creating circular reasoning rather than a rational, evidence-based belief.

4. Evidence Alone is Insufficient for True Belief

While commitment may require more than evidence, rational belief argues that commitment without evidence risks blind allegiance. Rational belief calls for alignment with verifiable facts before any personal commitment is justifiable. Deep conviction or heartfelt commitment may be powerful, but without evidence to ground it, such belief can drift toward wishful thinking rather than a truth-oriented approach.

5. Faith as Transformative Knowledge

Transformation alone does not validate truth; many beliefs may lead to personal change without being grounded in reality. While transformative experiences are valuable, rational belief contends that evidence must support any belief to ensure it reflects objective reality. Faith without evidence risks becoming self-reinforcing and insular, transforming a person based on subjective conviction rather than an accurate alignment with truth. Rational transformation derives from beliefs grounded in empirical and logical evidence, ensuring personal growth is tethered to reality.

Clarifications

Syllogistic Representation

Premise 1: Rational belief requires that the degree of belief is proportionate to the degree of evidence supporting it.

Premise 2: Any belief that is not proportionate to the degree of evidence is not rational (an inferior epistemic model).

Premise 3: Beliefs that are not rational lead to flawed perceptions of reality.

Premise 4: Flawed perceptions of reality result in decisional blunders.

Conclusion: Therefore, any belief that is not proportionate to the degree of evidence leads to decisional blunders.

Expanded Explanation:

- Rational Beliefs and Evidence: Rationality in belief demands alignment between the strength of one’s belief and the supporting evidence. A rational belief cannot exist without being proportionate to the evidence.

- Non-Evidence-Proportionate Beliefs are Irrational: If a belief does not align with the evidence, it fails the criterion of rationality and is considered an inferior epistemic model.

- Irrational Beliefs Lead to Flawed Perceptions: Holding irrational beliefs distorts one’s understanding and perception of reality, leading to errors in judgment.

- Flawed Perceptions Cause Decisional Blunders: Misinterpreting reality due to flawed perceptions inevitably results in poor decision-making.

Symbolic Logic Representation

Definitions:

Let:

: x is a belief

: x is evidence-proportionate

: x is rational

: x is an inferior epistemic model (irrational belief)

: x leads to flawed perceptions

: x results in decisional blunders

Premises:

All rational beliefs are evidence-proportionate.

Any belief that is not evidence-proportionate is an inferior epistemic model (irrational).

Any inferior epistemic model leads to flawed perceptions.

Flawed perceptions result in decisional blunders.

Logical Derivation:

- From Premise 1, the contrapositive is:

If a belief is not evidence-proportionate, it is not rational.

Therefore, Premise 2 can be restated using the definition of :

Since , this aligns with Premise 2.

Using Hypothetical Syllogism:

- From Premise 2 and Premise 3:

Beliefs that are not evidence-proportionate lead to flawed perceptions.

From the above and Premise 4:

Therefore, beliefs that are not evidence-proportionate result in decisional blunders.

Conclusion:

Any belief that is not proportionate to the degree of evidence leads to decisional blunders.

Summary:

By logically connecting the premises, we establish that holding beliefs without proportionate evidence undermines rationality, leads to flawed perceptions, and culminates in poor decision-making. This underscores the necessity of aligning one’s degree of belief with the supporting evidence to maintain a sound epistemic model and avoid decisional errors.

The Drive for “Knowledge” and Unwarranted Belief

Humans have a deep-seated drive to attain knowledge, a need that underpins much of our cognitive and emotional lives. This drive, while a cornerstone of human progress, often leads individuals to overestimate their certainty in areas where the evidence is weak or ambiguous. In pursuit of understanding and control, people sometimes cultivate unwarranted levels of belief in claims that do not have the corresponding support from facts or reliable data. This tendency can be seen in diverse areas such as pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and extreme political ideologies, where belief systems flourish despite limited or contradicting evidence.

One of the primary motivations behind this drive is the desire for certainty. Certainty provides a psychological comfort, reducing anxiety by creating a structured worldview that feels reliable and understandable. Uncertainty, on the other hand, leaves individuals vulnerable to ambiguity, which can be uncomfortable or even frightening. This discomfort often pushes people to adopt firm beliefs in propositions that lack adequate evidential grounding, merely to satisfy the craving for security and mental clarity. As a result, people may embrace ideas prematurely or cling to beliefs doggedly, not because the evidence warrants such conviction, but because doing so provides a sense of knowing and control.

Another force driving unwarranted belief is the social reinforcement of knowledge claims. People tend to seek out communities that affirm their beliefs, where group consensus amplifies individual certainty. When a claim, however unsupported, is widely accepted or validated by peers, individuals are more likely to overrate its validity. This social confirmation reinforces belief without necessarily increasing the factual basis behind it, creating an illusion of knowledge that feels robust but is actually built on shaky ground. In such environments, the drive to know is satisfied by community affirmation rather than by rigorous, evidence-based inquiry.

Finally, the allure of special knowledge or the feeling of having insights that others lack can also fuel unwarranted belief. Many individuals are drawn to ideas that appear exclusive, complex, or hidden from the mainstream, finding a sense of identity and intellectual superiority in these beliefs. This can lead to what is known as “epistemic overconfidence,” where the desire to possess unique insights overrides caution and critical thinking. The attraction of “secret knowledge” can cause people to embrace claims that stand on the fringes of credibility, motivated not by the strength of evidence but by the psychological rewards of feeling uniquely informed.

In essence, the human drive to know can paradoxically lead to epistemic pitfalls where belief and evidence are misaligned. The psychological comfort of certainty, the social reinforcement of consensus, and the allure of exclusive knowledge all play into this dynamic, encouraging people to settle on beliefs with unwarranted confidence. While this drive has contributed to both personal and collective advancement, it also demands vigilance: to seek genuine knowledge requires a commitment to evidence proportionate belief, remaining open to doubt, and resisting the comfort of certainties that the evidence does not justify. Only by balancing our drive for knowledge with epistemic humility can we avoid the pitfalls of unwarranted belief and approach true understanding.

“Thinking in Bets” by Annie Duke transforms how we approach decisions by encouraging us to think like poker players: seeing choices as informed bets rather than matters of certainty. Duke, a former professional poker champion, introduces the powerful concept of “resulting”—our tendency to evaluate decisions based solely on outcomes rather than on the quality of the decision-making process itself. She argues that outcomes can be influenced by factors outside our control, and therefore, focusing only on results can lead to flawed reasoning and reinforce bad habits. Instead, Duke teaches us to focus on the quality of our decisions, making choices that reflect probabilities, risks, and evidence, regardless of the ultimate outcome. This book is packed with practical strategies to challenge our biases, accept uncertainty, and become more resilient decision-makers in every aspect of life. Ideal for anyone who wants to make smarter, more calculated choices—whether in business, relationships, or personal growth.

The Logical Incoherence of a “Leap of Faith”

The concept of a “leap of faith”—committing unreservedly to a belief in the absence of corresponding evidence—presents serious logical incoherence when analyzed through the lens of rational belief and evidence-based decision-making. In rational terms, belief demands a degree of confidence that matches the strength of available evidence. However, a “leap of faith” bypasses this standard, promoting a binary commitment where one either believes fully or not at all, regardless of evidence. This approach, prevalent in religious contexts, conflicts with the epistemic standards that underpin rational thinking and sound decision-making. Such a leap can lead to cognitive distortion, flawed decision-making, and ultimately unsustainable belief systems, whether in faith or any domain requiring evidence-responsiveness.

One core problem with a “leap of faith” is that it encourages epistemic rigidity over flexibility. Rational belief, as demonstrated in Annie Duke’s Thinking in Bets, hinges on evidence-proportionate belief—the practice of adjusting one’s confidence according to the strength and balance of evidence. Rational belief functions as a dynamic alignment with the evidence, constantly recalibrating to reflect the best available information. At the poker table, a leap of faith might mean going “all in” without any supporting hand or strategy, leading to painful losses when the evidence doesn’t match the bet. Just as such irrational gambles can quickly drain a poker stack, leaps of faith can result in misguided actions and decisional blunders in nearly all areas of life. This is true in personal decisions, professional judgment, and financial investments, where faith-based leaps can overlook risks and result in significant losses.

Furthermore, a leap of faith relies on emotional certainty rather than logical grounding. In Thinking in Bets, Duke explains resulting, the error of judging decisions based solely on outcomes rather than the quality of the decision-making process. In a leap of faith, individuals often focus on the emotional comfort of certainty rather than on the quality of evidence. This creates a cognitive bias where people hold beliefs with absolute certainty despite partial or ambiguous evidence. While this can offer psychological stability, it ultimately produces cognitive dissonance, since the belief is rooted more in wishful thinking than in reality. This approach easily results in decisional blunders in life, where relying on unsupported confidence over actual evidence can lead to repeated setbacks and missed opportunities.

Theologically, faith is often depicted as an epistemic virtue, where trust in divine authority supersedes the need for evidence proportionate to belief. Religious perspectives, like those explored in the Christian Thought Survey, suggest that faith should be unwavering, with doubt seen as a weakness or failure of commitment. From a rational standpoint, however, trust without evidence creates logical problems, as it relies on authority without transparent verification. In rational thought, any claim to authority must come with credentials or demonstrable reliability. Without these, faith risks becoming circular reasoning, with the source of belief becoming its own justification. Like betting everything on a poker hand without checking the cards, taking an unsupported leap of faith risks substantial loss in life’s choices.

Additionally, the “leap of faith” promotes the idea of transformation as validation—arguing that deeply held beliefs transform a person’s outlook or moral character, which evidence-based beliefs cannot match. However, personal transformation does not confirm the truth of the underlying belief. While a leap of faith may bring subjective conviction, it fails to ensure truth alignment with external reality. In poker, one might feel euphoric betting on an unlikely hand, but this feeling does not change the actual odds of winning. Similarly, personal transformations based on unsupported beliefs run the risk of self-reinforcing illusions that ultimately mislead rather than clarify. Rational belief, by contrast, advocates for transformation grounded in evidence, so that growth aligns with reality, not subjective hope.

Finally, the leap of faith creates a binary belief model in which certainty is seen as morally superior to intellectual caution or doubt. Rational belief, however, holds that belief operates along a continuum, allowing for degrees of confidence that reflect degrees of evidence. This continuum promotes epistemic humility—recognizing that certainty should be proportional to the strength of evidence. In the leap of faith, certainty is elevated as a virtue, turning doubt into an intellectual failing. This mindset prevents truth-seeking, as beliefs resistant to scrutiny and revision risk becoming dogmatic rather than open to evidence. Just as overconfidence in poker leads to risky, ill-informed bets, binary faith in any domain risks acting on overblown confidence rather than the realities of the situation.

In conclusion, the leap of faith is logically incoherent within a rational framework, disregarding principles of evidence alignment, epistemic flexibility, and truth-seeking. Such a leap leads to flawed perceptions of the world, confirmation bias, and decisional blunders that parallel the kinds of losses seen at the poker table when irrational bets are made without strong hands. Rational belief—grounded in evidence and open to adjustment—is the superior model, both in pursuit of truth and in practical life decisions. This approach avoids the risks inherent in leaps of faith and promotes intellectual integrity that benefits all areas of life where informed, balanced beliefs are essential.

Leave a reply to Ron Morley Cancel reply