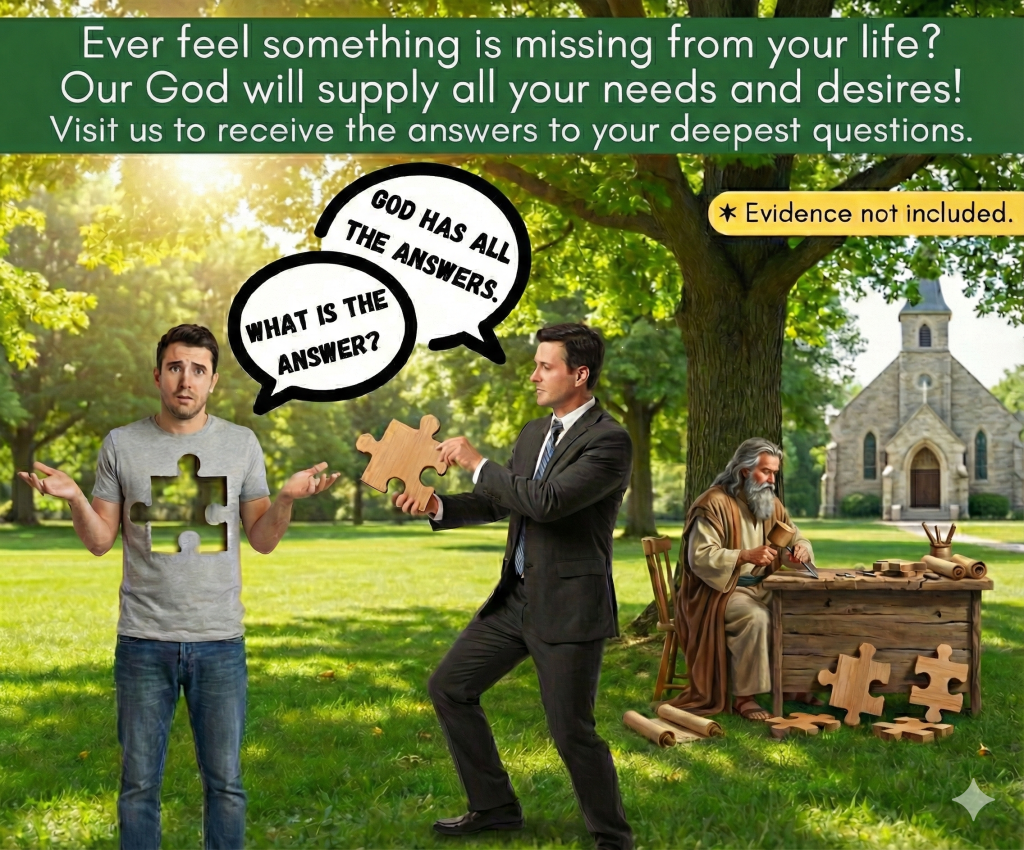

Consider the Following:

Summary: Christianity provides a wide range of answers to life’s profound questions, offering emotional comfort and meaning without the constraints of scientific evidence or falsifiability. However, the capacity to address these questions extensively does not inherently validate the truth of these answers, as they remain untested and unverifiable.

Imagine an ideological framework that purports to answer life’s most profound questions: What is the purpose of life? Why do we suffer? What happens after we die? Religion, and Christianity in particular, provides narratives that address these questions in ways that can be deeply compelling. But does this breadth of response genuinely indicate truthfulness, or does it reveal an adeptness in creating satisfying narratives?

Unlike science, which is bound by evidence and empirical testing, religions have the flexibility to craft answers that fit our deepest existential needs without the constraints of verification. Christianity, specifically, presents an extensive array of answers to questions that humans have pondered for centuries. However, does providing answers to these questions inherently validate the truth of those answers?

The Power of Unfalsifiable Answers

Religions hold a distinctive position when it comes to addressing life’s questions. They can formulate answers unbounded by empirical evidence or scientific scrutiny, which gives them the freedom to offer narratives that are both complete and internally consistent. Christianity, for instance, provides answers that may be emotionally satisfying but are structured in a way that makes them difficult, if not impossible, to disprove. This very unfalsifiability allows for the preservation of beliefs that science might otherwise challenge.

Consider the way Christianity responds to specific questions:

- What is the purpose of life?

- Christianity teaches that humans exist to glorify God and seek eternal life through Jesus Christ.

- Why is there suffering?

- Christianity proposes that suffering entered the world through sin and serves to test faith, build character, or fulfill divine purposes.

- What happens after death?

- Christianity posits an afterlife where the righteous are rewarded in heaven and the sinful face eternal separation from God.

- Where did we come from?

- Christianity claims that humans were created by God, specifically in his image, with an inherent purpose.

- Is there absolute justice?

- Christianity answers affirmatively, with the promise of divine judgment where all will be held accountable in the afterlife.

- How should we live our lives?

- Christianity provides ethical guidelines based on the teachings of Jesus and the Bible.

This extensive list of questions reflects Christianity’s scope and adaptability. It offers answers that, on their face, provide meaning, purpose, and reassurance. Yet, this freedom to offer expansive and unverifiable answers does not inherently reflect the truth of these claims. Rather, it emphasizes the flexibility of religious storytelling.

Does the Quantity of Answers Imply Truth?

Having numerous answers does not correlate with having truthful answers. If a system is free to create explanations without accountability to evidence or falsifiability, it can generate an endless number of satisfying yet unverifiable responses. This is not unique to Christianity. Many religions and belief systems provide internally consistent answers to life’s mysteries, but consistency does not equal validity.

Consider an example from folklore: If I claim that a spirit called a “house sprite” is responsible for lost items, I could create an elaborate narrative around this being’s actions and motivations. This story may be internally consistent, comforting, and even explanatory. However, without evidence or the possibility of disproving this claim, it remains a story rather than a reflection of truth.

The same principle applies to religious answers. Christianity’s answers may be consistent and emotionally resonant, but without a method to substantiate these answers, they remain untested beliefs.

When History Confronts Religious Explanations

Historically, religious explanations have often been supplanted by scientific understanding. For instance, ancient religious beliefs explained natural events—such as lightning—as acts of gods or expressions of divine will. These explanations provided meaning and were widely accepted. However, science eventually uncovered the natural causes of lightning, rendering the religious answers obsolete.

This historical pattern suggests that religion can provide temporary “answers” to satisfy human curiosity or fear, but these answers do not necessarily reveal truths about the universe. Rather, they reflect humanity’s need for meaning in a world that can appear indifferent.

The Comfort of Answers vs. The Reality of Truth

Ultimately, the ability to answer profound questions with packaged answers does not automatically validate the answers themselves. Christianity, like many religions, offers a worldview that addresses the human desire for purpose, justice, and continuity beyond death. But while these answers may provide emotional comfort, they do not constitute evidence of truth. The quantity of answers Christianity provides highlights its adaptability and capacity to meet psychological needs rather than offering any factual basis for its beliefs.

In summary, while Christianity provides a vast and interconnected set of answers to life’s questions, this ability to answer does not imply truth. The freedom to present unfalsifiable answers enables religions to appear all-encompassing and satisfying but does not serve as evidence that these answers reflect reality.

An Explanation of the Graphic: Coherence vs. Testability in Religious and Mythical Beliefs

The graphic illustrates the difference between internally coherent but untestable concepts and coherent, testable concepts as they pertain to religious and mythical beliefs.

On the left side, labeled the Infinite Set, we see a collection of entities like “God X,” “God Y,” “God Z,” demons, and angels. These entities represent concepts that are internally coherent (i.e., they follow a logical structure within their own framework) but are untestable by science. This untestability arises because these beings are often defined as immaterial, non-interactive, or existing beyond the realm of empirical investigation. As a result, any belief in these entities can persist without challenge because science cannot verify or falsify claims that lack measurable characteristics.

On the right side, labeled the Finite Verified Set, there are entities such as atoms, DNA, bears, and whales—these are coherent and testable by science. These elements exist in a finite set that can be empirically investigated, verified, and potentially falsified through scientific methods. In this category, claims are subject to evidence-based scrutiny and can be validated or disproven over time.

Between these two sets is the Unverified Set, which includes mythological or speculative entities like Bigfoot, mermaids, and space aliens. These entities may have characteristics that, in theory, could be testable, but they remain unverified due to a lack of reliable evidence. While there are claims and stories around these beings, their existence has not been scientifically confirmed.

The question marks between the categories for ghosts and fairies indicates that their categorization depends on whether these entities are defined in a way that can be scientifically tested. So long as they these entities don’t lend themselves to testability, they remain in the unsubstantiated and unsubstantiable domain on the left with most if not all Gods.

The “set” graphic above demonstrates that untestable entities occupy an “infinite” category because there is no limit to the number of possible coherent, imaginative explanations that can be proposed without evidence. Testable entities, however, are finite because they are constrained by the observable universe and the limitations of empirical investigation.

Key Insight: Religions, by including untestable, coherent entities, provide answers that are immune to scientific scrutiny, which can lend these beliefs a sense of permanence and resilience in the absence of empirical validation.

A Companion Technical Paper:

See Also:

◉ CS Lewis — Argument from Innate Desires

Dialogue:

😇 Everyone needs clear answers to the biggest questions — what our purpose is, where morality comes from, what our destiny will be. Christianity gives me all of that. Without it, people like you are left confused and hopeless.

🤔 I don’t deny that those are emotionally compelling questions. But notice: what you’ve listed are really desires, not neutral questions about reality. Wanting a castle doesn’t prove the gold mine exists beneath the hill. The promise of a gold mine may be accepted by those who feel incomplete without a castle, but the promise itself doesn’t produce evidence.

😇 But aren’t those desires evidence in themselves? Why would we long for meaning, justice, and hope unless there was a God who provided them?

🤔 That’s like saying our desire for treasure proves there must be buried treasure somewhere. Human desires tell us a lot about psychology, not necessarily about external reality. If we project our needs outward and mistake them for evidence, we collapse “what I wish to be true” with “what is true.”

😇 Still, Christianity offers clarity. I don’t have to say “I don’t know.” Isn’t that better than the uncertainty you’re defending?

🤔 But clarity is only valuable if it tracks reality. A forged map can give you very clear lines and labels, but if it doesn’t match the terrain, it leads you astray. “I don’t know” is not hopelessness; it’s intellectual honesty. Rational belief is not binary affirmation but a degree of confidence that must map to the degree of evidence.

😇 So you’re saying it’s better to be left in confusion than to have faith?

🤔 I’m saying it’s better to endure discomfort than to accept closure that isn’t earned. Real discovery begins when we resist the temptation of easy answers and let evidence guide us. If the castle is real, the gold mine will reveal itself with evidence. But if all we have is the promise, believing too quickly may stop us from ever finding what’s true.

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Unfalsifiable Claims and Perceived Truth

- Premise 1: Religions, including Christianity, provide internally coherent answers to profound questions, which do not require scientific verification.

- Premise 2: Internally coherent answers that are unfalsifiable (not subject to scientific scrutiny) cannot be disproven by empirical evidence.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the presence of internally coherent but unfalsifiable answers in religions does not imply these answers reflect truth but rather highlights the adaptability of religious storytelling.

Argument 2: Quantity of Answers vs. Truthfulness

- Premise 1: Christianity and other religions provide a wide range of answers to fundamental existential and moral questions, which often meet human psychological needs.

- Premise 2: Providing a large number of answers does not guarantee the truthfulness of those answers, especially if they lack empirical verification.

- Conclusion: Thus, the quantity of answers that Christianity provides does not equate to the truth of those answers; it only demonstrates an ability to satisfy human curiosity and psychological needs.

Argument 3: Freedom from Scientific Scrutiny and Religious Claims

- Premise 1: Christianity and other religions are not bound by scientific scrutiny, allowing them to provide answers that may be comforting but remain untestable.

- Premise 2: Concepts that are untestable are immune to falsification, which means they cannot be proven or disproven through scientific methods.

- Conclusion: Consequently, the freedom from scientific scrutiny allows Christianity to maintain beliefs that provide emotional satisfaction, but this freedom does not establish the truth of those beliefs.

Argument 4: Historical Examples of Religious Explanations

- Premise 1: Historically, many religious explanations for natural phenomena, such as attributing lightning to divine will, provided satisfying answers before scientific explanations were available.

- Premise 2: Over time, science has replaced many religious explanations with empirical evidence-based answers, demonstrating that religious answers were not truthful but merely temporary solutions to unknowns.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the historical pattern of scientific advancements replacing religious explanations indicates that religious answers may provide comfort but do not necessarily reflect truth.

Argument 5: Coherence and Verifiability

- Premise 1: Entities that are coherent and testable by science exist within a finite verified set that can be empirically investigated and either confirmed or falsified.

- Premise 2: Entities that are coherent but untestable exist within an infinite set and can never be disproven if they lack empirical characteristics.

- Conclusion: Thus, while coherence provides internal consistency, it does not imply truthfulness unless coupled with verifiability through scientific methods.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Examining Christianity’s Claims and the Nature of Truth

CHRIS: Christianity provides answers to the most profound questions in life—questions about purpose, suffering, justice, and the afterlife. Isn’t the fact that Christianity addresses these existential concerns evidence that it’s the true path?

CLARUS: I understand that Christianity offers a comprehensive set of answers to these questions, but the mere ability to provide answers doesn’t automatically equate to truthfulness. A system of beliefs can be internally coherent and emotionally satisfying, but still lack a basis in reality if it isn’t subject to empirical verification.

CHRIS: But isn’t it compelling that Christianity has answers for so many existential questions? Surely, this scope of explanation points to something real, something more than random invention.

CLARUS: Not necessarily. The ability to answer many questions is often a result of freedom from scientific scrutiny. Christianity and other religions aren’t required to verify their answers in the way science is. Religions can construct narratives that are untestable, meaning they’re protected from disproof. Just because something can’t be proven false doesn’t make it true.

CHRIS: Are you saying that because Christianity’s claims aren’t scientifically testable, they’re invalid?

CLARUS: I’m saying that untestable claims are neither validated nor invalidated by science—they’re simply unverified. Historically, religions often provided explanations for phenomena like lightning or disease before science developed evidence-based answers. Those religious answers met psychological needs at the time, but they weren’t true. Over time, empirical science replaced them with verifiable explanations.

CHRIS: But what about the existential answers that science can’t touch, like the meaning of life or the existence of God? Doesn’t Christianity’s consistent, coherent approach to these questions imply its truthfulness?

CLARUS: Consistency and coherence don’t imply truthfulness without verifiability. I can create a coherent story about invisible fairies stealing lost keys, and it might even be satisfying. But if that story includes elements that are untestable, it remains a narrative rather than a reflection of reality. Coherence alone isn’t enough to establish truth—the testability of claims matters.

CHRIS: So you’re saying that untestable concepts, like many of those in Christianity, are potentially infinite because they’re beyond falsification?

CLARUS: Exactly. There’s an infinite set of possible untestable entities and explanations, limited only by human imagination. But the set of entities that are coherent and testable by science—like atoms, DNA, and species we can observe—is finite. Religions, by allowing for untestable entities, have the freedom to construct answers that may feel complete but aren’t subject to the same standards of truth as scientific claims.

CHRIS: But what if Christianity offers a level of comfort and hope that science simply can’t provide? Isn’t that valuable in itself?

CLARUS: Absolutely, the comfort Christian assertions provides can alleviate many human fears and worries. But comfort and truth are different matters. Christianity’s capacity to comfort does not establish its truthfulness. A belief system can fulfill psychological needs without accurately describing reality. Truth requires more than just satisfying answers—it requires answers that withstand scrutiny and verification.

CHRIS: I see your point. You’re saying that while Christianity may answer deep questions in a way that feels meaningful, this doesn’t confirm its factual accuracy. The answers might be internally consistent but still lack empirical support.

CLARUS: Precisely. The fact that Christianity offers extensive, coherent answers reflects its adaptability and appeal to human psychological needs, but this doesn’t inherently make those answers true. A system that avoids falsifiability can appear all-encompassing, but that very unfalsifiability is why we can’t assume it accurately represents reality.

CHRIS: I appreciate your explanation. It’s a challenging perspective to consider, especially when we’re so used to equating coherence and comfort with truth. I’ll need to think more about the role verification plays in understanding reality.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Detective’s Infinite Suspects

Imagine a detective trying to solve a mystery with no eyewitnesses or physical evidence. With no constraints, the detective can create an infinite list of suspects—from unknown strangers to imaginary characters—each with a detailed backstory and motive. While these hypothetical suspects might offer a coherent explanation for the crime, they are unhelpful without any testable evidence to support them. Similarly, religious answers to existential questions, while coherent, can include untestable elements that prevent verification, leaving them in the realm of hypothetical narratives rather than truth.

Analogy 2: The Invisible Bridge Builder

Imagine a community claiming that an invisible bridge builder constructed a bridge overnight. The bridge is visible and functional, but there is no evidence of the builder’s existence beyond the community’s word. They insist that this invisible builder is the only explanation, and because he is defined as undetectable, there’s no way to verify or disprove his involvement. Just like this unfalsifiable claim, many religious explanations rely on invisible or supernatural agents that cannot be subjected to scientific scrutiny. The claim might be internally consistent but lacks the verifiability required to establish truth.

Analogy 3: The Comforting Map of Imaginary Lands

Imagine someone creating a detailed map of an imaginary land, complete with mountains, rivers, and towns. The map is coherent and follows all the rules of cartography, making it easy to understand and even comforting to envision as real. However, if the land it represents doesn’t exist, the map, while detailed, is ultimately a fiction. Similarly, Christianity and other religions offer comprehensive answers to life’s questions that can feel comforting, but without empirical evidence, these answers resemble a well-drawn map of an imaginary place—satisfying but not necessarily a reflection of reality.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. The Limitation of Empirical Science on Spiritual Matters

A theologian might argue that empirical science is inherently limited to the physical realm and therefore cannot address spiritual or metaphysical questions. Just as science doesn’t attempt to answer questions about love or purpose with hard evidence, religious answers aim to provide meaning rather than scientific verification. From this perspective, untestability doesn’t diminish the value or truth of spiritual insights, as they operate in a different domain from empirical inquiry.

2. The Universality of Existential Questions and Their Answers

Theologians might argue that the widespread existence of certain existential questions across cultures and history suggests an innate human need for answers that go beyond material explanations. Religions, especially Christianity, provide responses that address this universal human longing for understanding life’s purpose, justice, and the afterlife. The comprehensive nature of Christianity’s answers could thus be seen as evidence that it addresses fundamental truths about human existence that empirical methods overlook.

3. The Role of Coherence as Indication of a Divine Design

A theologian could argue that the internal coherence within Christianity, as well as its ability to address diverse human experiences and questions, suggests a divine origin. While coherence alone doesn’t establish empirical truth, theologians might propose that a consistent worldview across varied aspects of life points to a higher design. This cohesive structure in Christianity’s teachings could be viewed as evidence that its answers come from an intelligent and purposeful source.

4. Historical Validation Through Lived Experience and Tradition

Theologians might emphasize the historical resilience of Christianity and the way its teachings have been validated by the experiences and testimonies of countless believers. Christianity has endured over millennia, shaping societies and inspiring people to lead meaningful lives. Theologians may argue that practical, lived validation—from personal transformation to communal moral guidance—serves as a different form of evidence that complements empirical knowledge.

5. Faith as a Necessary Foundation Beyond Empirical Limits

Theologians often assert that faith itself is a response to the limits of human knowledge and the inability of science to address certain questions. Faith allows individuals to accept truths that lie beyond the reach of evidence but are crucial for personal and moral development. Theologians may argue that faith-based answers to existential questions should not be dismissed merely because they are untestable, as they provide an essential foundation for a meaningful life that science cannot supply.

6. The Complementary Roles of Science and Religion

Some theologians view science and religion as complementary rather than contradictory. They might argue that science explains the mechanisms of the physical world, while religion addresses the “why” behind existence and purpose. By providing answers to metaphysical questions—which science cannot measure or validate—Christianity complements scientific understanding, contributing to a fuller picture of reality that encompasses both empirical and spiritual dimensions.

Counter-Responses

1. Science’s Scope and the Testability of Spiritual Claims

While it’s true that empirical science is limited to the physical realm, many religious claims extend into domains that directly impact the observable world, such as miracles or answered prayers. When religions make assertions that should, in principle, have detectable effects—such as divine intervention in human affairs or the efficacy of prayer—these claims should be testable. If a claim has real-world implications, then evidence becomes relevant, and a failure to verify such claims may suggest they do not accurately reflect reality.

2. Universal Questions Do Not Validate Specific Religious Answers

The presence of universal existential questions does not imply that any particular set of religious answers is true. The fact that humans across cultures seek meaning and purpose may simply reflect a psychological need for narratives that make life’s difficulties more bearable. Different cultures have produced vastly different answers to these same questions, which suggests that existential needs drive the creation of comforting explanations rather than pointing to any specific truth in one religious framework, including Christianity.

3. Coherence Does Not Equal Truth

While internal coherence within a belief system may make it appear logically consistent, coherence alone does not imply truthfulness. A coherent story can be entirely fictional—just as fictional universes in literature can be internally consistent without reflecting reality. The cohesiveness of Christianity’s worldview could simply reflect its ability to adapt and reinterpret its doctrines over time, rather than any indication of a divine design. Truth requires more than coherence; it requires external verification.

4. Lived Experience as Subjective Validation, Not Objective Evidence

While personal testimonies and historical endurance may offer subjective validation for some, these elements do not constitute objective evidence of a religion’s truth claims. Many belief systems, some of which contradict Christianity, have also endured and positively impacted individuals and societies. Personal experiences, while powerful, are vulnerable to confirmation bias, cultural influence, and emotional needs, which makes them unreliable indicators of universal truth.

5. Faith Does Not Justify Beliefs Beyond Evidence

Faith may indeed address questions that science cannot answer, but this does not make faith-based answers true or justifiable. Resorting to faith to accept untestable claims does not confer any epistemic authority on those beliefs. Faith, in the absence of evidence, merely reflects a psychological commitment rather than a rational endorsement. Embracing faith as a foundation for answers could simply mean accepting comforting assumptions without the necessary scrutiny to determine their validity.

6. Science and Religion as Complementary is Problematic

The claim that science and religion are complementary ignores the fundamental difference in their methods. Science relies on evidence, falsifiability, and the willingness to discard incorrect hypotheses, whereas religion often resists revision even in the face of contradictory evidence. If religions make claims about the “why” of existence, these claims remain speculative without evidence to back them. True complementarity would require that both fields uphold similar standards of verification, which is not the case with religious beliefs that are resistant to empirical testing.

Clarifications

Intellectual and Emotional Questions Addressed by Religions Through Untestable Answers

1. What happens after we die?

Religions frequently claim to provide answers about the afterlife, presenting ideas such as heaven, hell, reincarnation, or eternal soul existence. For example, Christianity teaches that the faithful will enter heaven, while those who reject its tenets face eternal separation from God in hell. Hinduism and Buddhism offer answers in the form of reincarnation or spiritual liberation. These concepts are untestable because they rely on non-physical realms or immaterial souls that lie beyond empirical observation, making them impossible to confirm or disprove scientifically. They provide emotional comfort by alleviating the fear of oblivion without requiring any verifiable evidence.

2. What is the purpose of life?

Religions often assert that human life has a divinely ordained purpose. For example, in Christianity, believers are taught that their purpose is to worship God and live according to His will, aiming for eternal life in God’s presence. This answer provides emotional fulfillment and direction but is untestable because it presumes the existence of a transcendent deity with specific intentions for human life, which cannot be empirically investigated or measured. As such, this answer functions as a narrative tool rather than a verifiable statement about the human condition.

3. Why is there suffering and evil in the world?

The problem of evil is a central intellectual question for which religions provide varied answers. Christianity, for instance, often explains suffering as a result of original sin, human free will, or as a test of faith and character that ultimately leads to spiritual growth. These answers imply a divine purpose behind suffering that is beyond human comprehension. Such explanations offer psychological comfort but are untestable, as they rely on assumptions about an unobservable divine plan and moral justifications that cannot be validated. The existence of suffering and evil remains unsolved by evidence, leaving these answers as philosophical assertions rather than verified truths.

4. Does justice exist beyond human society?

Religions frequently claim that ultimate justice exists in a divine realm, even if not realized on Earth. For example, Christianity teaches that God will administer final judgment after death, rewarding the righteous and punishing the wicked. This concept of divine justice addresses emotional needs for fairness in a world where justice is often imperfect. However, it is untestable because it presumes the existence of a supernatural judicial system that cannot be observed or measured. There is no way to verify that divine justice is real, making it a comforting yet speculative solution to human dissatisfaction with earthly justice.

5. Why does the universe exist?

Many religions offer creation stories that explain the origin of the universe. For instance, Abrahamic religions teach that God created the universe out of nothing, motivated by His will or purpose. This explanation satisfies intellectual curiosity about cosmic origins but remains untestable, as it involves a transcendent act beyond the realm of empirical investigation. Science offers explanations like the Big Bang Theory but does not address the ultimate “why” behind existence, whereas religious explanations assume intentional divine causation without evidence to substantiate this claim.

6. Is there meaning in suffering or hardship?

Religions often claim that suffering has a greater purpose beyond human understanding. For example, some religious frameworks suggest that hardship is meant to build character, cleanse karma, or prepare believers for a better life after death. This provides emotional solace by assigning purpose to seemingly senseless suffering. However, this answer is untestable, as it assumes an invisible mechanism or cosmic plan that cannot be empirically validated. The idea that suffering is meaningful operates on an assumptive belief rather than observable evidence, functioning more as a psychological comfort than a factual explanation.

7. Is there a way to gain supernatural protection or intervention?

Religions frequently claim that prayer, rituals, or sacrifices can lead to divine intervention or protection. For instance, many faiths teach that by praying or performing specific rituals, believers can invoke divine aid or ward off evil. While these practices may foster a sense of security or empowerment, their effects remain untestable and unproven beyond the psychological benefits of ritual. Claims that supernatural beings respond to human requests are not observable and often rely on confirmation bias or subjective interpretation rather than objective validation.

8. Are there moral absolutes dictated by a higher power?

Religions frequently assert that moral values are derived from divine commandments, such as the Ten Commandments in Christianity or the Five Precepts in Buddhism. This claim provides a sense of moral authority and certainty in ethical decision-making. However, it is untestable because it assumes the existence of an invisible deity who defines morality without providing empirical evidence. The notion of divinely ordained moral laws functions as a moral framework but remains speculative without any verifiable source beyond religious doctrine.

9. Can we communicate with divine beings or spirits?

Many religions teach that humans can communicate with deities or spiritual entities through prayer, meditation, or rituals. For example, Christianity encourages prayer as a means to speak to God and receive guidance, while other traditions promote contact with spirits for healing or insight. These practices fulfill the emotional need for connection with a higher power but are untestable because there is no observable interaction that can be measured. Claims of divine communication rely on personal belief and subjective experience, which cannot be corroborated by objective evidence.

10. Why do people die at different times and in different ways?

Some religions claim that death occurs according to a divine plan or cosmic purpose, suggesting that when and how people die is beyond human understanding but meaningful within a larger framework. For example, some Christian teachings hold that God determines the time of each person’s death as part of His will. This explanation can provide comfort in the face of unexpected loss but is untestable because it presupposes a hidden divine reasoning behind individual life spans. Such claims are ultimately philosophical assertions without empirical support, offering emotional relief rather than a scientifically grounded explanation.

These examples illustrate how religions often provide untestable answers that fulfill psychological needs rather than empirical inquiries. While they address fundamental intellectual and emotional questions, their lack of verifiability means they remain within the realm of narratives and beliefs, rather than validated truths.

Leave a reply to Phil Stilwell Cancel reply