Consider the Following:

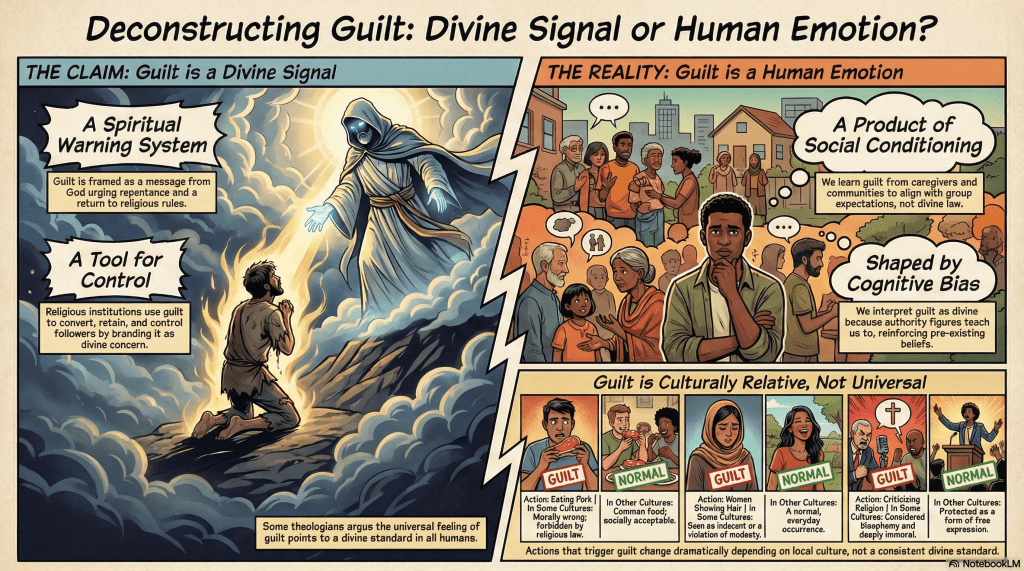

Summary: Religious institutions often interpret feelings of guilt as evidence of divine judgment, co-opting this natural emotion to reinforce their teachings and maintain control over followers’ behavior. However, guilt is shaped by cultural and social influences, making it a psychological response rather than proof of any divine presence.

Imagine a young girl who is taught from a young age that wearing earrings and makeup is sinful and offensive to a supreme being who demands strict obedience. When she eventually tries on these items, she experiences guilt, which she interprets as the disapproval of this deity. But is her feeling of guilt true evidence of divine conviction, or could it be a product of social conditioning?

“They feel guilty because they are guilty.”

“God has made us moral creatures and we are ethically guilty. To put it simply, people feel guilt because they are guilty.”

— A Frequent Claim of Apologist Greg Koukl

This example is not unique. Around the world, people are conditioned to interpret guilt as a sign of spiritual wrongdoing, often reinforcing religious beliefs. However, the specific actions considered “sinful” and the corresponding guilt vary widely across cultures. While one culture may regard wearing jewelry as neutral, another may view it as “immoral”. This inconsistency raises questions: if guilt were genuinely divine, why would it arise from behaviors that depend so heavily on cultural norms? Is guilt really a message from a higher power, or a reflection of social and psychological influences?

Natural Origins of Guilt: Social Conditioning and Cognitive Development

Psychologists explain that guilt is an emotion deeply embedded in the process of socialization. From a young age, people learn to associate guilt with behaviors that violate the values of their caregivers and communities. Repeated reinforcements teach children to feel guilt when they act against these expectations, embedding these feelings in their moral framework. In the case of the young girl, guilt over wearing earrings and makeup is not an innate signal of sinfulness but rather an internalization of her family’s and community’s beliefs.

Cultural Anthropology and the Diversity of “Moral” Norms

Cultural anthropology shows that guilt is influenced by social norms and varies across cultures. A woman may feel guilty for wearing makeup in a conservative society but might feel entirely unburdened in a liberal one. These differences suggest that guilt does not arise from any universal divine source but rather from contextual “moral” standards that cultures impose.

The Role of Cognitive Biases and Authority Indoctrination

In addition, cognitive biases can lead individuals to interpret feelings of guilt as proof of divine judgment. When authority figures repeatedly link guilt with spiritual messages, it conditions individuals to expect guilt as a sign of divine displeasure, reinforcing the belief that guilt confirms divine reality.

How Religious Authorities Co-opt Guilt as “Evidence” of Divine Presence

Religious leaders and doctrines frequently seize upon feelings of guilt, framing them as evidence of a “convicting spirit” or divine presence. This approach exploits a natural emotion, positioning guilt as a pathway to religious conviction and obedience.

- Framing Guilt as a Divine Warning:

Many religions claim that guilt is more than a natural response; they suggest it’s a signal from God urging believers to repent and return to prescribed moral behavior. This framing allows religious authorities to attribute natural emotional responses to a supernatural cause, providing “evidence” of divine engagement in people’s daily lives. By claiming that guilt originates from a “convicting spirit,” religious leaders co-opt a universal emotion to validate the teachings of their particular faith. This tactic convinces believers that each pang of guilt they feel is direct evidence of a higher power’s concern for their moral decisions. - Leveraging Guilt for Conversion and Retention:

Religious institutions often use guilt not only to keep followers but also to bring new converts into the fold. Many religions emphasize the notion of “sin” and “repentance,” presenting guilt as a divine call to “return” to God. This tactic exploits the common experience of guilt to encourage introspection aligned with religious teachings. For instance, if individuals feel guilt over actions deemed sinful by religious doctrines—such as premarital sex or questioning authority—religious teachings capitalize on these feelings to draw individuals toward religious rituals of repentance, which they claim alleviate divine displeasure. In effect, guilt becomes a tool for maintaining control over personal behavior. - Justifying Doctrine through the Universality of Guilt:

Some religious traditions argue that the very fact that guilt is a universal emotion serves as proof of their doctrines. They contend that everyone’s experience of guilt points to a higher moral authority instilled within humanity. However, this interpretation ignores substantial evidence that guilt is influenced by upbringing, culture, and social expectations rather than a divine law. By attributing guilt to the “spirit of God,” religious leaders convert a common psychological response into a perceived spiritual phenomenon, encouraging adherents to view guilt as irrefutable proof of their faith’s validity. - Amplifying Guilt through Doctrinal Teachings:

Many religious doctrines actively intensify feelings of guilt by introducing an ever-expanding list of “sins.” Individuals are taught to monitor their thoughts, words, and actions meticulously, leading to frequent encounters with guilt. When believers internalize these messages, they begin to experience guilt for minor or natural behaviors, interpreting these emotions as reminders of their “fallen” state and their need for divine guidance. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where believers see guilt as ongoing evidence of divine scrutiny and their need for religious guidance, all while feeling dependent on the religion for forgiveness and relief.

Comparing Guilt with Other Emotionally Driven Responses

While guilt is compelling, it is not unique among emotions in how it drives behavior. For example:

- Jealousy over a partner’s interactions does not validate possessive beliefs.

- Resentment toward a peer’s success does not confirm a higher entitlement.

- Shame after failure does not indicate absolute unworthiness.

These emotions, like guilt, arise from a combination of personal experiences and social conditioning. The fact that guilt feels powerful does not confirm its divine origin. Instead, like jealousy or shame, it is a complex response, reflecting the psychological and social processes that shape our behavior.

Conclusion: Rethinking Guilt as Evidence of the Divine

Considering the natural, culturally influenced origins of guilt—and how religious institutions co-opt guilt as a tool of control—it becomes clear that guilt alone is not evidence of divine judgment. If guilt truly indicated divine displeasure, it would arise consistently across cultures for the same actions, independent of societal norms. Instead, guilt is variable, shaped by social expectations, cultural standards, cognitive biases, and indoctrination.

- P1: If guilt can be explained by natural socialization, cultural influence, cognitive biases, and religious indoctrination, it does not reliably indicate divine presence or will.

- P2: Evidence shows that guilt is culturally dependent, often arising from social conditioning rather than universal moral truths.

Therefore: Guilt, while influential, is not reliable evidence of divine conviction. It is an emotion that religious authorities frequently co-opt to sustain adherence and validate their doctrines, yet it remains a fundamentally human experience, rooted in the social and psychological fabric of human life rather than divine intervention.

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Social Conditioning as the Basis of Guilt

- Premise 1: Feelings of guilt are shaped through socialization, where behaviors are learned and reinforced according to cultural and familial norms.

- Premise 2: If guilt were truly indicative of divine disapproval, we would expect guilt-provoking behaviors to be consistent across cultures, independent of social context.

- Conclusion: Therefore, guilt is not a reliable indicator of divine judgment but rather a product of social conditioning.

Argument 2: Cultural Variation of “Moral” Codes

- Premise 1: Cultural anthropology shows that guilt-provoking behaviors vary significantly across societies, with different cultures instilling unique “moral” codes.

- Premise 2: If guilt were a universal signal of divine displeasure, it would correspond to a uniform set of actions across all cultures.

- Conclusion: Thus, the variability of guilt suggests it aligns with culturally specific behavioral expectations, not an absolute divine standard.

Argument 3: Cognitive Biases Reinforcing Guilt as Divine Evidence

- Premise 1: Cognitive biases such as confirmation bias lead individuals to interpret guilt as a sign of divine conviction, especially when this interpretation is reinforced by religious authorities.

- Premise 2: When individuals expect guilt to signal divine judgment, they are more likely to interpret it this way, even when no inherent “moral” transgression has occurred.

- Conclusion: Therefore, guilt may feel like divine conviction due to cognitive biases, but this interpretation lacks objective grounding.

Argument 4: Religious Institutions’ Co-opting of Guilt

- Premise 1: Religious authorities often frame guilt as proof of a “convicting spirit” or divine presence, claiming it is a sign of God urging individuals to align with prescribed “moral” standards.

- Premise 2: This framing of guilt as divine evidence relies on interpreting natural emotional responses to suit religious doctrines, without objective proof of divine origin.

- Conclusion: Consequently, religious institutions co-opt guilt to reinforce adherence to their teachings, even though guilt itself does not substantiate the presence of a divine being.

Argument 5: Emotional Responses Do Not Imply Divine Judgment

- Premise 1: Emotions like jealousy, resentment, and shame are complex responses to social and psychological factors and do not signify divine judgment.

- Premise 2: Guilt, as one of these emotions, serves a motivational purpose but is equally subject to social and psychological conditioning.

- Conclusion: Therefore, guilt, like other emotions, is not evidence of divine displeasure but a human psychological response.

Argument 6: Unreliable Evidence for Divine Conviction

- Premise 1: If guilt can be explained by socialization, cultural influence, cognitive biases, and religious indoctrination, it lacks a basis as an objective indicator of divine will.

- Premise 2: Evidence shows that guilt is often culturally specific and shaped by authority-driven social expectations.

- Conclusion: Therefore, guilt is not a reliable form of evidence for divine conviction but is instead influenced by human social constructs.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Is Guilt Evidence of Divine Conviction?

CHRIS: It seems to me that the guilt we feel when we’ve done something wrong is a clear indication of God’s presence in our lives, convicting us of our sins. If we didn’t have this convicting spirit, how else would we know that we’re breaking divine laws?

CLARUS: I understand where you’re coming from, but feelings of guilt don’t inherently prove divine involvement. Psychological research suggests that guilt largely results from social conditioning—our values are shaped by the culture and family we grow up in. If guilt were universally tied to God, we’d see people across all cultures feeling guilty for the same actions, yet what’s considered “sinful” varies widely across societies.

CHRIS: But doesn’t the very existence of guilt in all cultures point to a universal moral standard? Even if societies differ on specifics, the fact that we all experience guilt shows we have a deep sense of right and wrong, one that I’d argue is God-given.

CLARUS: The universality of guilt actually doesn’t imply a divine moral order. Cultural anthropology shows that guilt aligns with culturally specific codes of behavior. For example, a woman in a conservative society might feel guilty for wearing makeup, whereas in another culture, makeup might be encouraged. If guilt were truly divine, we’d expect it to arise from a universal set of “sins,” but instead, it’s shaped by social expectations that vary.

CHRIS: I see, but even within a culture, don’t people often feel guilty without any obvious reason? For instance, a Christian might feel guilt even without anyone explicitly condemning their actions, which suggests an internal conviction—couldn’t this be evidence of God working within?

CLARUS: That’s an interesting point, but cognitive biases like confirmation bias can lead people to interpret emotions, such as guilt, as divine. If you’ve been taught that guilt means God is displeased, you’re more likely to feel it’s divine when you experience guilt, even if it’s just a conditioned response. This interpretation doesn’t objectively prove that guilt originates from God; it’s more a result of how people frame their experiences.

CHRIS: But religious doctrines emphasize guilt and repentance as pathways to purity and closeness with God. Doesn’t that suggest a spiritual source behind guilt?

CLARUS: Religious institutions indeed capitalize on guilt, often framing it as a “convicting spirit” to encourage obedience. However, that’s part of a cycle where guilt is used to reinforce belief, not necessarily because it’s divine but because it’s effective at maintaining adherence to the faith. By framing guilt as divine, religious authorities co-opt a natural emotional response, making it appear as though guilt itself validates their doctrines, which doesn’t objectively demonstrate divine involvement.

CHRIS: So you think religions are just using guilt to control people?

CLARUS: I’d say that religions often amplify feelings of guilt to sustain their authority. They expand the list of “sins” so people feel guilt even over minor actions, like your example of a Christian feeling guilty without an external reason. This tactic keeps believers dependent on religious forgiveness, but it doesn’t prove guilt has a divine origin. It’s more about social and psychological control.

CHRIS: But we all experience other strong emotions too, like jealousy or resentment, and we don’t see those as divine messages. So why should guilt be different?

CLARUS: Exactly. Emotions like jealousy or shame drive our actions, but we don’t attribute them to a higher power. Guilt, like these emotions, serves a purpose in guiding behavior but reflects social and psychological conditioning rather than divine judgment. Just because guilt feels powerful doesn’t mean it has a supernatural source.

CHRIS: So in your view, guilt is just… human, not divine?

CLARUS: Yes, I’d argue that guilt is a human response shaped by our upbringing, culture, and cognitive biases. If guilt were really divine, it would be consistent across all cultures and societies, pointing to the same “moral” truths. Instead, it’s highly variable, which suggests that guilt, while significant, is rooted in social expectations rather than in a divine will.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The “Traffic Light” of Social Norms

Imagine driving in a foreign country where the traffic lights follow an unfamiliar color scheme—perhaps purple means “stop” and green means “yield.” At first, you feel uneasy, as though you’re doing something wrong when obeying this unfamiliar system. This unease is not because there’s an objective moral law in traffic lights; it’s simply the result of being conditioned to follow a specific set of rules. Similarly, guilt operates as an emotional response conditioned by cultural norms. Just as one’s traffic light “intuition” changes with the environment, guilt is a learned reaction aligned with the “moral” signals set by one’s society.

Analogy 2: The “School Dress Code” of Cultural “Morality”

Imagine growing up in a school with a strict dress code that considers wearing jeans “unacceptable.” Students who break this rule feel embarrassed or guilty, fearing punishment or judgment from teachers. However, in other schools, wearing jeans might be completely normal or even expected. This variation shows that guilt isn’t tied to an objective wrong but to the social standards within a given community. In the same way, religious institutions capitalize on socially imposed guilt, framing it as a divine standard, even though the feeling itself results from arbitrary norms, much like a dress code.

Analogy 3: The “Parental Approval” Effect

Consider a child who feels guilty when they displease their parents, even over harmless actions like choosing an unpopular hobby. The guilt doesn’t come from the inherent “sinfulness” of the hobby but from the fear of parental disapproval. As the child grows, they may still feel guilt over these choices, conditioned to see certain actions as “wrong” based on authority figures’ opinions. Similarly, religious guilt arises from indoctrinated expectations, with authority figures positioning guilt as divine “disapproval.” Yet, like parental approval, this guilt doesn’t confirm an objective standard; it reflects a conditioned response to social or religious authorities.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Guilt as a Universal Moral Compass

Theologians might argue that the universality of guilt across cultures suggests an innate moral compass that points to a divine source. While the specifics of guilt-provoking actions may vary, the underlying sense of “oughtness” in human conscience could indicate a God-given moral law embedded in all people, reflecting a shared sense of right and wrong beyond social conditioning.

2. Cultural Variation Does Not Eliminate Divine Standards

While different societies have distinct norms, theologians could contend that this cultural variation doesn’t negate the existence of a divine standard. Instead, they might argue that human fallibility leads to distorted moral understandings across cultures. The underlying principle of guilt still points toward a higher divine truth, with some cultures closer to it than others.

3. Cognitive Biases Can Coexist with Divine Influence

Theologians might agree that cognitive biases influence how we interpret emotions like guilt, but they would argue this doesn’t preclude divine involvement. They might claim that God uses guilt to convict individuals, even if human psychology shapes its manifestation. Cognitive biases could be seen as a natural means through which divine conviction operates, allowing humans to interpret God’s guidance in ways familiar to their personal experiences.

4. Religious Teachings on Guilt Reflect Divine Wisdom

In response to the claim that religious authorities exploit guilt for control, theologians might argue that doctrines on sin and repentance exist to guide individuals toward a higher moral path. They would assert that guilt, when properly understood, is a divine tool meant to lead people to self-reflection, humility, and growth, rather than a mere psychological tool for authority. The teachings, they might contend, are intended to help individuals align with God’s will, not to manipulate.

5. Divine Guilt as Different from Human Emotions

Theologians could argue that guilt is distinct from other emotions like jealousy or shame because it specifically involves a sense of moral failure. They might suggest that this unique quality of guilt indicates divine engagement with human conscience. While other emotions are often ego-centered, guilt might be seen as selfless and redemptive, a form of spiritual insight meant to guide one’s moral development in accordance with divine standards.

Counter-Responses

1. Rational Response to Guilt as a Universal Moral Compass

While guilt is a common emotion, its universality does not necessarily indicate a divine source; rather, it can be explained through evolutionary psychology. Social cohesion is vital for human survival, and guilt functions as a social tool to encourage behaviors that align with group norms, ensuring cooperation and trust. This perspective explains why guilt is widely felt yet differs in what it responds to, as it adapts to diverse cultural and social contexts rather than pointing to any absolute or divine moral standard.

2. Rational Response to Cultural Variation and Divine Standards

Claiming that cultural variation in “moral” codes reflects “distorted” understandings of a divine standard is circular reasoning unless one can demonstrate that a divine standard exists in the first place. Without clear, independent evidence for such a standard, appealing to “distortion” doesn’t address why guilt aligns with cultural norms rather than universal ones. The observable fact is that guilt arises from socialization processes, adapting to local standards and contexts, which is more consistent with a naturalistic explanation than with divine influence.

3. Rational Response to Cognitive Biases and Divine Influence

Invoking divine influence alongside cognitive biases raises the question of why such biases would be necessary if guilt were truly divine. If a deity were communicating through guilt, the message would logically be direct and consistent rather than filtered through biased, fallible psychology. The existence of cognitive biases suggests that guilt is more likely an evolved psychological mechanism influenced by social contexts than a reliable indicator of divine judgment.

4. Rational Response to Religious Teachings on Guilt Reflecting Divine Wisdom

The claim that guilt in religious teachings is a divine tool for “moral” guidance ignores the fact that guilt is often weaponized by religious authorities to maintain control over believers. History is full of examples where institutionalized guilt has been used to enforce obedience, often for purposes far removed from any genuine character growth. Furthermore, guilt’s alignment with culturally specific “sins” undermines its reliability as a divine tool; if it were divinely sourced, it would consistently target universally harmful behaviors rather than reinforcing arbitrary religious or cultural rules.

5. Rational Response to Divine Guilt as Different from Human Emotions

While guilt involves behavioral expectations and considerations, this does not distinguish it as a divine emotion; it simply reflects the social importance of pro-social behavior in human communities. The fact that guilt often promotes behavior aligned with group cohesion suggests an evolutionary, not supernatural, origin. Guilt is similar to other emotions in that it motivates actions beneficial to social harmony, indicating that it functions as an adaptive social mechanism rather than a unique spiritual insight or evidence of divine engagement.

Clarifications

Distinguishing Psychogenic from Theogenic Guilt: The Need for a Coherent Methodology

In examining guilt, individuals often encounter two perspectives: psychogenic (psychological) and theogenic (divinely inspired). If some guilt is recognized as psychologically induced and potentially unjustified, then a method becomes essential for distinguishing between feelings of guilt rooted in psychological conditioning and those allegedly arising from divine influence. This essay argues that, to maintain coherence, one must develop a reliable approach for discerning when guilt arises solely from social or psychological factors and when it may reflect a divine source.

Defining Psychogenic and Theogenic Guilt

Psychogenic guilt refers to guilt stemming from internalized social norms, cultural expectations, and personal psychology. This form of guilt is typically learned through socialization and reflects the attitudes and values prevalent in one’s community or upbringing.

Theogenic guilt, in contrast, is presumed to be a response to a universal standard or divine will that goes beyond cultural and social influences. Those who view guilt as theogenic argue that certain feelings of guilt indicate a genuine alignment with a higher source of guidance.

Given these distinctions, the challenge becomes determining whether guilt in specific cases arises from psychological or social conditioning alone or could genuinely indicate divine influence. Without a method to assess this distinction, interpretations of guilt risk becoming arbitrary and unreliable.

The Problem of Cultural Relativity and Variability in Guilt

One major obstacle in differentiating psychogenic from theogenic guilt is the cultural variability of guilt-inducing actions. Diverse societies assign guilt to a wide range of behaviors—examples include women showing their faces in public, same-sex relationships, or the consumption of certain foods. These culturally specific guilt responses suggest that guilt is often influenced by social conditioning rather than universal standards.

If guilt were purely theogenic, we would expect to see a consistent response to certain actions globally, regardless of cultural context. The lack of uniformity in guilt-inducing actions casts doubt on guilt’s reliability as a universal indicator of any higher standard, highlighting the need for a structured approach to separate culturally induced guilt from guilt that could be considered independent of social norms.

Cognitive Bias and Psychological Influences

Cognitive psychology offers significant evidence that guilt can be influenced by cognitive biases and personal conditioning, which complicates the claim that guilt reliably indicates divine influence. For example, confirmation bias can lead people to interpret guilt as an external warning when they are predisposed to view it that way, while authority bias can induce guilt over behaviors condemned by respected figures or institutions.

These cognitive mechanisms indicate that guilt is often a subjective response influenced by emotional states, beliefs, and social pressures. Without a method to filter out biases and subjective influences, distinguishing psychogenic guilt from theogenic guilt becomes problematic. If guilt can arise independently of any divine or absolute standard, relying on it without a coherent evaluation system risks confusing personal or cultural biases with supposed universal insights.

Criteria for Distinguishing Psychogenic from Theogenic Guilt

For guilt to function as a dependable indicator of anything beyond social conditioning, a coherent and rigorous method must address the following criteria:

- Universality: A coherent method should assess whether the guilt arises consistently across cultures and societies. Theogenic guilt, if valid, would presumably reflect universal standards rather than culturally specific taboos. Hence, guilt that differs across cultures is more likely psychogenic.

- Objective Harm: A reliable indicator of theogenic guilt would involve actions that produce objective harm or significant disruption. Guilt over actions that are socially neutral or harmless is more likely a product of socialization than an independent signal.

- Independence from Authority Bias: True theogenic guilt should arise without reliance on human authority figures or institutional rules. If guilt emerges primarily because of pressure from authority, it is more likely psychogenic, influenced by social obedience.

- Consistency in Personal Beliefs: A coherent method would evaluate whether guilt aligns consistently with a person’s own reflections, rather than fluctuating with social or situational pressures. If guilt varies based on social settings or authority influences, it is likely psychogenic.

- Alignment with Principles of Well-being: Guilt that emerges in response to behaviors that disrupt well-being, cause harm, or degrade communal trust could suggest a broader basis for interpretation. Guilt felt in contexts not related to well-being may indicate psychological conditioning.

Practical Application of the Method

Applying these criteria can help distinguish between psychogenic and theogenic guilt. For example, consider a woman in a conservative society who feels guilt for showing her face in public. If her guilt fails the tests of universality (as not all societies find this wrong) and objective harm (since no harm results from showing her face), it would be reasonable to interpret her guilt as psychogenic. Alternatively, guilt arising after direct harm caused to another may align more readily with principles related to broader interpersonal well-being.

By systematically applying these standards, individuals can start to separate guilt stemming from psychological or cultural influences from guilt that might reflect an alignment with broader, less context-bound insights. This approach offers a way to assess guilt without relying on subjective emotional interpretation alone.

Conclusion: The Need for Methodological Rigor

The distinction between psychogenic and theogenic guilt is essential for clear analysis. Without a method to discern between them, guilt remains an unreliable and subjective response, prone to personal, cultural, and cognitive biases. By developing a disciplined system based on universality, objective harm, independence from authority bias, consistency, and well-being alignment, individuals can better evaluate guilt as either a personal or broader social response, fostering a more structured understanding of its significance.

Distinguishing Psychogenic from Theogenic Guilt: The Need for a Coherent Methodology

To distinguish between psychogenic (psychological) and theogenic (presumably divine) feelings of guilt, a scientific test would need to isolate specific characteristics that are unique to either form. Below is a proposed experimental framework to investigate this distinction, based on examining cultural consistency, neural activation patterns, and predictive validity.

Experimental Framework: Distinguishing Psychogenic from Theogenic Guilt

1. Cross-Cultural Consistency Assessment

- Objective: Determine if the feelings of guilt arise universally across diverse cultural groups or are culturally specific.

- Hypothesis: If a feeling of guilt is truly theogenic, it should consistently appear across different cultures for the same actions, suggesting a universal basis. In contrast, psychogenic guilt should vary based on cultural norms and upbringing.

- Method:

- Select culturally diverse participants from a wide range of societies (e.g., Western, Eastern, Indigenous, and traditional religious communities).

- Present each group with scenarios involving actions that are both culturally specific (e.g., showing one’s face in public) and theoretically universal (e.g., causing harm to another person).

- Assess and record the guilt responses for each scenario.

- Analysis: If certain guilt responses are universal (e.g., guilt from causing harm to another), they may indicate a shared human response. If guilt responses differ widely based on cultural context (e.g., guilt over attire), they likely reflect psychogenic guilt tied to social conditioning.

2. Predictive Validity and Longitudinal Behavioral Consistency

- Objective: Assess whether psychogenic or theogenic guilt better predicts changes in behavior over time, regardless of social pressures.

- Hypothesis: If guilt has a theogenic foundation, it should drive behavior changes more consistently across different social contexts, as it would theoretically stem from an intrinsic, non-social source.

- Method:

- Conduct a longitudinal study tracking individuals who have reported feelings of guilt (categorized as either psychogenic or theogenic) over several years.

- Categorize initial guilt feelings based on cultural specificity and the factors that initially triggered the guilt.

- Measure whether these guilt responses consistently influence behavior over time, regardless of changing social contexts (e.g., does a person continue to avoid certain actions despite moving to a society where those actions are culturally accepted?).

- Analysis: If guilt responses that are more universal (possibly theogenic) lead to more stable and consistent behavioral changes across different social contexts, this could suggest a different foundation than culturally specific (psychogenic) guilt, which might weaken or change in new social environments.

Combined Results Interpretation

The results from these three tests could help distinguish psychogenic from potentially theogenic guilt by examining cultural universality and behavioral consistency over time. If a form of guilt is universal across cultures, and leads to behavior change independent of social pressures, it might suggest a more intrinsic origin, one that some could interpret as aligning with theogenic guilt.

However, it’s crucial to note that even if such a pattern is observed, further philosophical and scientific investigation would be needed to interpret whether this pattern truly indicates a “theogenic” basis or simply reflects a universal aspect of human psychology.

Morally Controversial Actions Across Cultures

These activities often elicit unwarranted feelings of guilt.

- Women Showing Their Faces or Hair in Public – In certain Muslim-majority countries, women are expected to cover their faces or hair in public as an act of modesty. Uncovered faces are seen as morally indecent, while in other countries, showing one’s face is entirely unproblematic.

- Engaging in Same-Sex Relationships – Same-sex relationships are often deemed immoral and may even be criminalized in some countries, particularly in conservative or religious societies, while in many other countries, these relationships are fully accepted and legally recognized.

- Consuming Alcohol – In several Islamic countries, drinking alcohol is considered immoral and is sometimes punishable by law, seen as a violation of religious values, whereas in other cultures, alcohol consumption is normalized and socially acceptable.

- Publicly Criticizing Religious Figures or Beliefs – In countries where blasphemy is strictly prohibited, criticizing or questioning religious beliefs or figures is seen as deeply immoral and can lead to legal punishment. In contrast, in secular societies, such criticism is considered a matter of free expression.

- Women Driving or Traveling Alone – In some conservative cultures, it is considered improper or immoral for women to drive or travel unaccompanied by a male guardian, as it is believed to defy societal norms on gender roles. In other cultures, women driving or traveling alone is entirely normal.

- Eating Pork – In Islamic and Jewish cultures, consuming pork is considered morally wrong, as it is viewed as unclean and contrary to religious teachings. However, pork is a common and unremarkable food in many other countries.

- Interfaith Marriages – Marrying outside of one’s religious community is often considered morally unacceptable in some cultures, where it is seen as disloyal or sacrilegious. Conversely, interfaith marriages are common and accepted in many societies.

- Premarital Relationships and Intimacy – In some cultures, particularly those with conservative or religious views, premarital relationships are considered immoral, and engaging in them can bring shame or social penalties. In contrast, premarital relationships are widely accepted in secular societies.

- Eating Meat – In some Hindu and Jain communities, eating meat is considered morally wrong due to beliefs about non-violence toward animals. Vegetarianism is seen as a moral imperative, whereas meat consumption is normal and widely practiced in many other cultures.

- Women Speaking Loudly or Publicly Asserting Themselves – In some traditional societies, women are expected to be quiet and reserved, and publicly asserting themselves or speaking loudly can be seen as morally improper. In other countries, self-expression and assertiveness are encouraged regardless of gender.

- Renouncing One’s Religion – In some countries, apostasy (the act of renouncing one’s religion) is considered morally reprehensible and may even be punishable by law. In contrast, freedom to change or abandon religious beliefs is protected and respected in other societies.

- Tattooing or Body Modification – In certain cultures, particularly conservative or religious ones, tattooing or body modification is considered immoral as it is seen as defiling the body. In other cultures, tattoos are a common and socially accepted form of self-expression.

- Wearing Revealing Clothing – In some conservative societies, wearing clothes that reveal arms, legs, or shoulders is considered morally wrong for women, as it is viewed as immodest. In many other cultures, such attire is standard and acceptable.

- Gambling – Gambling is considered morally wrong in some religious societies, especially in Islamic countries, where it is viewed as unethical and harmful. However, in other societies, gambling is socially accepted and even celebrated as a form of entertainment.

- Practicing or Endorsing Atheism – In highly religious societies, atheism or lack of belief in a deity is considered immoral and sometimes even punishable. In contrast, in secular societies, atheism is considered a personal belief and is fully accepted.

- Failing to Perform Ancestral or Religious Rituals – In certain cultures, failing to perform rituals for ancestors or religious ceremonies is considered morally wrong, as it is seen as neglectful of one’s duties. In other societies, such rituals are optional and not morally binding.

- Divorcing – In some cultures, particularly those with strong religious influences, divorce is seen as morally unacceptable and may carry social stigma, as it is believed to undermine family values. However, in many societies, divorce is accepted as a personal choice.

- Living Together Before Marriage – In some conservative and religious societies, cohabitation before marriage is considered morally wrong, often associated with a lack of respect for traditional values. In contrast, cohabitation is a common and accepted practice in other cultures.

- Engaging in Public Displays of Affection – Public displays of affection between couples are seen as morally inappropriate in some conservative societies, especially in parts of Asia and the Middle East. However, in many Western societies, public displays of affection are viewed as normal expressions of love.

- Practicing Non-Monogamy or Polyamory – Non-monogamous relationships are considered immoral in many traditional societies that prioritize monogamous marriage. However, in some modern cultures, polyamory and open relationships are seen as legitimate personal choices.

These examples illustrate that notions of morality are not universally consistent but instead reflect cultural and religious standards. Actions deemed immoral in some societies can be entirely acceptable or even celebrated in others, challenging the idea of an absolute moral standard tied to any divine authority.

Leave a comment