Consider the Following:

Summary: This argument challenges the notion that God’s hiddenness is necessary to preserve free will, asserting instead that clear evidence of God’s existence would enhance autonomy by enabling informed decision-making. A deity valuing rational choice would likely make His existence unmistakable, allowing for genuine freedom through knowledge rather than ignorance.

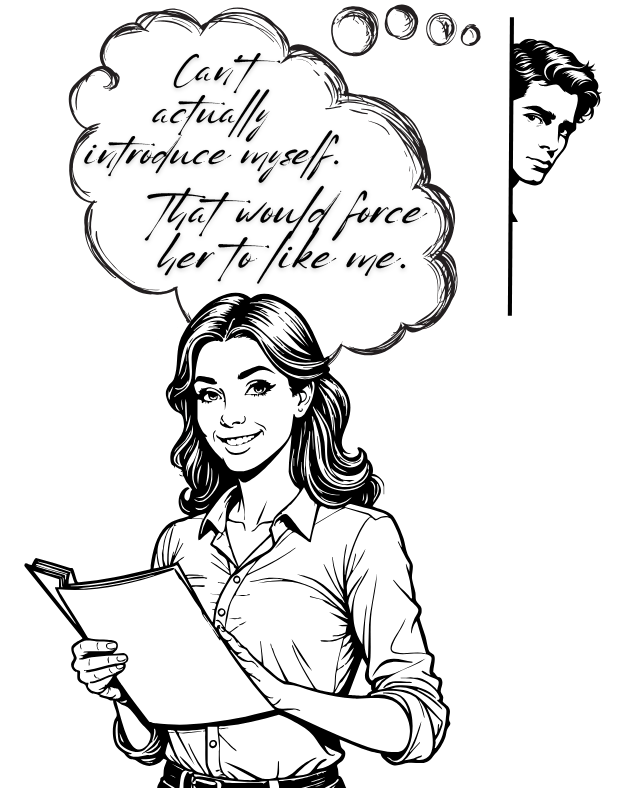

Imagine Jim wants Julie to marry him. He fears that if he openly reveals himself and meets her face-to-face, her freedom to choose him authentically might be compromised. In this situation, Jim’s fear seems absurd; clarity about who he is does not strip Julie of her ability to choose. This is akin to a common argument made by Christian proponents regarding God’s hiddenness: that an unequivocal appearance by God would take away human freedom to reject Him. But does this idea withstand critical examination?

If we turn to the biblical narrative, we see that Satan supposedly rejected God despite having direct evidence of His existence. If Satan could rebel with full knowledge, why would a clear revelation of God’s existence today strip humans of their choice? Let’s consider the nature of evidence, free will, and how a straightforward revelation by God could clarify our ability to make an informed decision without forcing acceptance.

Reasons a Direct Revelation from God Shouldn’t Impact Free Will

- Certainty Does Not Mean Compulsion

Certainty of God’s existence would provide people with clarity, not coercion. Freedom of choice does not require ignorance of options but rather the ability to choose among clear ones. Knowledge enables a well-informed decision; it doesn’t dictate acceptance. - Evidence Builds Trust

Just as a suitor would reveal himself before proposing, a deity demanding allegiance could be reasonably expected to provide clear evidence of His existence. Trust cannot flourish without evidence, and faith based on evidence is more rational and resilient. - Making Rational Choices

Asking someone to commit to an invisible deity may demand irrational loyalty. Would any rational person marry an unseen stranger? Demanding blind faith disregards human cognitive requirements for rational trust.

Counterarguments and Reflections on God’s Hiddenness

- Faith as the Basis for Love

A common argument suggests that God desires love rooted in faith rather than knowledge. Yet, imagine if Jim proposed to Julie without ever revealing himself, claiming that her acceptance would demonstrate “greater love.” This doesn’t foster a genuine connection; rather, it places a barrier of uncertainty between them, which could foster mistrust instead of love. - The ‘Seek and Find’ Argument

It’s argued that those who genuinely seek God will find Him. However, this notion is vulnerable to confirmation bias and lacks empirical grounding. History shows countless individuals seeking divine truth, only to arrive at beliefs in deities of vastly differing natures. The quest for God should be distinguishable from imaginative projection if it were a pursuit with a real, singular outcome.

Hypothetical Dialogue: What Would Jesus Say?

- MAN: Can I help you?

- JESUS: Yes, I’m Jesus, the Savior of humanity. I’d like to give you the opportunity to choose me.

- MAN: But if you’re really Jesus, wouldn’t that force my hand? My pastor says I’d lose my freedom to reject you if you revealed yourself too clearly.

- JESUS: Interesting. But let’s think about this. Does knowing who I am rob you of your freedom to walk away? Just as knowing a loved one is real doesn’t force you to love them, knowing I exist doesn’t compel you to follow me.

- MAN: But how would I really know it’s you? Isn’t faith about believing without proof?

- JESUS: There are simple, direct ways I could make myself known: I could appear simultaneously to people around the world, unmistakably in multiple languages and forms. I could also perform acts that leave verifiable evidence, such as healing incurable diseases. Would this take away your freedom to doubt or reject me?

- MAN: No, I suppose I’d still have my doubts or biases. But I could make a much more informed choice.

- JESUS: Exactly. Knowing I exist lets you exercise your choice based on reality. It doesn’t strip you of your freedom; it enhances your capacity to choose knowingly.

- MAN: So why hasn’t God done that?

- JESUS: That’s a question to reflect upon. If I am who I say I am, and I want a genuine relationship, would it make sense to remain hidden?

Logical Summary

- P1: Rational decision-making requires sufficient evidence to justify trust in any significant claim or relationship. Without adequate evidence, belief becomes arbitrary, undermining the reliability and integrity of the choice.

- P2: A benevolent deity would presumably value the well-being and autonomy of humans, thus providing enough clear evidence for them to make an informed decision. Requiring trust without evidence contradicts the principles of both rationality and autonomy, as it discourages decisions based on knowledge and agency.

- P3: If free will were compromised by evidence of God’s existence, then other forms of knowledge that lead to clear choices would also compromise free will. However, empirical evidence consistently shows that knowledge enables free choice rather than constraining it, as seen in countless life decisions where informed choice does not prevent autonomy.

- P4: Biblical and theological texts recount examples of beings with full knowledge of God’s existence—such as Satan and certain angels—who still retained the ability to accept or reject Him. Thus, knowledge of God’s existence does not inherently compel acceptance or allegiance.

- P5: If belief in God were central to humanity’s purpose, and if salvation or judgment were based on this belief, a just and benevolent God would logically ensure that evidence for His existence is unmistakably clear to maximize humanity’s freedom to choose responsibly.

- Conclusion: The traditional concept of a deity who withholds clear evidence to preserve free will is logically flawed. Instead, an unequivocal revelation of God would enhance genuine freedom, as people could then make fully informed choices without uncertainty. Therefore, a deity who values human autonomy and rationality would not hide but would make His existence demonstrable, allowing humans to engage their full capacity for informed, autonomous decision-making.

In summary, the logical coherence of God’s hiddenness as a necessity for free will is exceedingly weak. Evidence enhances the quality of choice, empowering individuals to exercise true autonomy. Thus, clarity of evidence would honor free will rather than diminish it, suggesting that the hiddenness argument does not hold up under rigorous scrutiny.

See also:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Rational Decision-Making Requires Evidence

- Premise 1: Rational decision-making requires sufficient evidence to justify trust in any significant claim or relationship.

- Premise 2: Without adequate evidence, belief becomes arbitrary and undermines the reliability and integrity of the choice.

- Conclusion: Therefore, rational decision-making about significant beliefs, such as belief in a deity, requires sufficient evidence to justify the trust placed in it.

Argument 2: A Benevolent Deity Would Provide Evidence

- Premise 1: A benevolent deity would prioritize human well-being and autonomy, which includes making informed choices.

- Premise 2: Providing clear evidence of existence would enable informed decision-making, honoring both rationality and agency.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a benevolent deity would logically provide sufficient evidence of His existence to allow humans to make informed and autonomous choices.

Argument 3: Knowledge Does Not Compromise Free Will

- Premise 1: If free will were compromised by knowledge of an option, then any informed choice would also restrict autonomy, which contradicts real-life observations.

- Premise 2: In practical contexts, informed choices enhance autonomy rather than diminish it, as demonstrated in countless everyday decisions.

- Conclusion: Therefore, knowledge of God’s existence would not inherently compromise free will but would instead enable genuine freedom through informed choice.

Argument 4: Biblical Evidence Shows Knowledge Does Not Compel Acceptance

- Premise 1: Biblical accounts include examples of beings, such as Satan and certain angels, who possessed full knowledge of God’s existence yet retained the freedom to reject Him.

- Premise 2: If these beings retained freedom of choice despite clear knowledge, then humans with similar knowledge would also retain freedom to accept or reject.

- Conclusion: Therefore, full knowledge of God’s existence does not compel acceptance and is consistent with the retention of free will.

Argument 5: Clear Evidence Maximizes Responsible Freedom

- Premise 1: If belief in God is central to humanity’s purpose and affects salvation or judgment, a just deity would ensure evidence of His existence is sufficiently clear for responsible choice.

- Premise 2: Without clear evidence, individuals may lack the necessary information to make a responsible and informed decision regarding such a significant choice.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a deity concerned with human freedom and responsibility would make His existence clearly evident, allowing humans to exercise genuine free will in an informed manner.

Final Conclusion: Clarity of Evidence Honors Free Will

- Premise 1: Rationality, autonomy, and responsibility are respected when humans make informed decisions based on clear evidence.

- Premise 2: A deity who values these qualities would logically ensure clarity of evidence regarding His existence.

- Conclusion: Thus, the argument that God’s hiddenness preserves free will is flawed; clear evidence of God would honor genuine freedom by allowing people to exercise informed, autonomous decision-making.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Role of Evidence in Free Will and Belief

CHRIS: Clarus, I believe that God remains hidden to protect our free will. If His existence were undeniably obvious, we’d be compelled to believe, and that would strip us of our freedom to choose Him.

CLARUS: But why would certainty about God’s existence remove our freedom to reject Him? Rational decision-making depends on having clear evidence, not on ignorance. Being informed doesn’t take away our autonomy; it empowers it.

CHRIS: I see what you’re saying, but doesn’t God want us to have faith without needing full proof? Faith that comes without clear evidence shows greater love and trust in Him.

CLARUS: I understand that perspective, but if God is a benevolent being who values both our well-being and autonomy, wouldn’t He prefer that we make decisions based on clear, informed evidence? Imagine a doctor asking you to take a treatment without explaining why it’s necessary—you’d be right to question them, and so would anyone with a rational mind.

CHRIS: Perhaps, but if we had absolute evidence of God’s existence, wouldn’t that force everyone to believe? Free will, in this context, is meaningful because we’re choosing without certainty.

CLARUS: Not necessarily. In life, knowledge doesn’t equate to compulsion. We often make informed choices—whether about careers, relationships, or personal beliefs—based on clear evidence. Just knowing the reality of something, like a job offer, doesn’t mean we’re forced to accept it. Evidence enhances freedom by allowing us to choose responsibly.

CHRIS: So you’re saying that knowledge of God’s existence would still leave us free to choose whether or not to follow Him, just as we might freely choose or reject any other clear option?

CLARUS: Precisely. In fact, biblical examples support this. Think of Satan and certain angels—they had full knowledge of God’s existence yet retained the ability to reject Him. If clear evidence didn’t force them to obey, why would it force us?

CHRIS: But if God made His existence crystal clear, wouldn’t that remove the need for faith altogether? Isn’t faith valuable for its role in guiding people without full proof?

CLARUS: Faith based on clear evidence is still valuable because it reflects a rational commitment rather than a blind leap. Trust in God, if He exists, could then be rooted in a well-founded understanding. Additionally, if salvation or judgment depends on our choice to believe, a just deity would logically want us to make that decision with all the facts in front of us, not in uncertainty.

CHRIS: So, you’re suggesting that a loving and just God would make His existence undeniable to ensure we have the freedom to make an informed choice rather than leaving us to guess?

CLARUS: Exactly. If a deity wants genuine, autonomous acceptance, He would honor our rationality and freedom by being clear. Just as we wouldn’t expect someone to marry an invisible suitor, we shouldn’t be expected to commit to a hidden deity. True freedom is not guessing in the dark but choosing in the light of knowledge.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Doctor and the Treatment

Imagine a doctor prescribes a life-altering treatment but refuses to explain why it’s necessary or how it works. The patient is told to trust the doctor’s judgment without any evidence or information. Just as blind faith in this doctor is unreasonable and could lead to uninformed decisions, so too would blind belief in a hidden deity compromise one’s freedom to choose responsibly. Informed consent requires clear evidence, empowering the patient to make a rational, autonomous choice. Similarly, clear evidence of God’s existence would respect human autonomy rather than undermining it.

Analogy 2: The Invisible Suitor

Imagine a person being asked to marry an invisible suitor whom they have never seen, heard, or touched. They are told that committing to this person without any proof of existence would show greater love and trust. In any ordinary relationship, trust builds on knowledge; the more you know about someone, the freer you are to love or reject them authentically. Expecting someone to make a commitment without clarity is unreasonable. Just as clarity in human relationships enables genuine freedom of choice, so would clear evidence of God enable people to make an informed, voluntary choice without losing autonomy.

Analogy 3: The Employee and the Job Offer

Consider a job offer from an unseen company that provides no information about the position, salary, or work culture. The potential employee is told to trust that it’s the right job, but without any tangible evidence, the choice becomes a gamble. In contrast, when a company provides detailed information, the employee has the freedom to make an informed decision based on genuine understanding. Similarly, if God’s existence were made clear and evident, individuals would be able to choose freely, supported by knowledge rather than uncertainty, making the decision more authentic and responsible.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. God’s Hiddenness Protects the Integrity of Faith

Some theologians argue that faith is valuable precisely because it involves trust without conclusive evidence. They may claim that certainty in God’s existence would diminish the spiritual depth of belief, as it would become less a matter of genuine trust and more a reaction to undeniable proof. In this view, faith without sight honors the voluntary commitment that God values.

2. Free Will Might Be Compromised by Absolute Knowledge

Another response posits that absolute knowledge of God’s existence would indeed affect free will, making rejection irrational and potentially coercive. Theologians who support this idea might argue that divine hiddenness allows individuals to make a genuine choice without feeling pressured by overwhelming proof, thus preserving their freedom to choose or reject God based on personal conviction rather than evident compulsion.

3. Suffering and Evil as Ways to Understand God’s Presence

Some theologians suggest that suffering and evil in the world serve as subtle forms of evidence for God’s presence, as they allow individuals to experience the need for redemption, compassion, and hope. From this perspective, direct evidence of God might limit humans’ ability to seek deeper spiritual truths found in life’s challenges. This hiddenness encourages individuals to turn inward, seeking God’s presence through faith rather than empirical confirmation.

4. God’s Revelation as Accessible through the Heart, Not Proof

Theologians may assert that God’s revelation is spiritual rather than empirical, experienced in the heart rather than through evidence. This perspective claims that God’s presence is clear to those who are open to it, allowing individuals to experience His reality through inner conviction rather than external proof. They argue that true faith transcends evidence, as it is a relationship built on personal, subjective experience with God rather than objective knowledge.

5. Respect for Human Intellectual and Spiritual Autonomy

A further response is that divine hiddenness respects human intellectual and spiritual autonomy by allowing people to form beliefs through reflection and inner searching. Theologians might argue that an overt demonstration of God’s existence would override individuals’ natural journey of spiritual discovery. In this view, hiddenness ensures that belief emerges from personal growth and self-determined searching rather than a forced acknowledgment of undeniable facts.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “God’s Hiddenness Protects the Integrity of Faith”

While the value of faith is often presented as trust without conclusive evidence, true integrity in decision-making is built on knowledge rather than uncertainty. Genuine trust is not undermined by clarity; rather, it is enhanced when it has a solid foundation. Faith based on clear evidence can foster a richer, more resilient belief that does not rely on ambiguity or guesswork but on informed commitment, allowing individuals to engage their full capacity for rational choice while still exercising freedom.

2. Response to “Free Will Might Be Compromised by Absolute Knowledge”

Free will is not threatened by absolute knowledge; rather, it is the lack of clarity that limits autonomous decision-making. In other areas of life, individuals regularly make choices based on clear knowledge without feeling compelled. For instance, knowing the factual consequences of dietary choices does not eliminate freedom but enables informed and responsible choices. Similarly, certainty of God’s existence would not compel acceptance but would allow individuals to exercise genuine freedom by choosing knowingly, not out of ignorance.

3. Response to “Suffering and Evil as Ways to Understand God’s Presence”

While theologians may view suffering and evil as ways to encounter God’s presence, relying on indirect and often painful experiences as indicators of a benevolent deity’s reality can seem counterintuitive. A just deity would likely provide clear, direct evidence rather than leaving individuals to interpret hardship as a sign of divine existence. Seeking God through suffering assumes that ambiguity is more beneficial than clarity, yet clarity would allow for a healthy, rational relationship with the concept of a deity, reducing the emotional confusion often associated with interpreting suffering as evidence of divinity.

4. Response to “God’s Revelation as Accessible through the Heart, Not Proof”

The claim that God’s revelation is solely a spiritual experience risks undermining the universality of belief, as subjective experiences vary widely and can be unreliable. Objective evidence provides a common ground for all individuals, regardless of personal disposition or emotional state, allowing for a universally accessible path to belief. A deity who wishes for a genuine relationship with humanity would likely value evidence-based accessibility to ensure that individuals can reach informed conclusions, rather than relying solely on subjective, internal experiences that may not translate into a stable or coherent understanding.

5. Response to “Respect for Human Intellectual and Spiritual Autonomy”

While respecting human intellectual autonomy is important, hiddenness can undermine autonomy by forcing people to make significant choices without necessary context or clarity. Autonomy is best respected when individuals are able to make informed decisions that reflect reality, rather than basing choices on guesswork or incomplete knowledge. If a deity’s aim is for individuals to choose freely, then providing evidence would actually enhance their intellectual and spiritual freedom, allowing them to act with both autonomy and insight rather than being confined to uncertainty.

Clarifications

Leading Christian figures who have claimed clarity reduces free will

Several religious leaders and theologians have articulated the idea that an undeniable revelation of God would compromise or diminish human free will, especially in the context of Christian theology. Here are some notable examples:

- C.S. Lewis: In The Screwtape Letters, Lewis suggests through the character Screwtape (a senior demon advising a junior demon) that if God were to reveal Himself undeniably, it would “override human will” by removing the possibility of doubt, which is necessary for genuine faith and choice. According to Lewis, humans need a “degree of obscurity” to freely choose faith in God.

- St. Augustine: Augustine touches on this idea in several works, notably in Confessions and The City of God. He argues that part of God’s decision to remain somewhat hidden allows individuals to seek Him voluntarily rather than being compelled by undeniable proof. Augustine held that faith without compulsion was a deeper expression of human choice and love for God.

- Pope Benedict XVI: In several writings, including his book Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict XVI discusses the value of faith that arises from an internal search and trust, as opposed to forced belief resulting from overwhelming evidence. He emphasizes that if God’s presence were too obvious, it would reduce the capacity for individuals to exercise genuine choice.

- Alvin Plantinga: As a prominent Christian philosopher, Plantinga has written about the concept of epistemic distance—the idea that God maintains a certain degree of hiddenness to allow humans to freely respond to Him. Plantinga argues that if God’s existence were overly evident, humans would be coerced into belief, undermining authentic free will.

- Richard Swinburne: In his book The Existence of God, Swinburne presents the idea that God provides “enough evidence” for belief but not so much that it would eliminate all doubt. This balance, Swinburne argues, preserves human autonomy by allowing individuals to choose belief without feeling forced.

- Tim Keller: In sermons and books, including The Reason for God, Keller has suggested that God’s partial hiddenness allows for a faith that is more about relationship than coercion. He argues that if God made Himself completely obvious, it would overwhelm personal freedom, and people would follow God out of compulsion rather than genuine love.

These leaders share a common view: that God’s hiddenness preserves free will by allowing for faith to be chosen, rather than forced. They suggest that an undeniable revelation of God’s existence would interfere with human autonomy by leaving people with no real choice in their response.

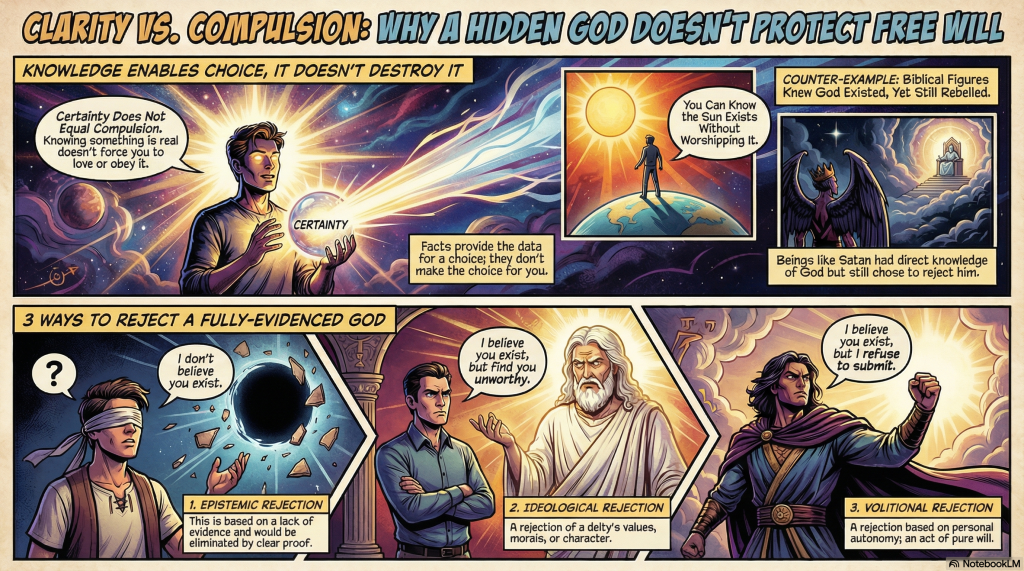

◉ The Three Modes of Rejection: Epistemic, Ideological, and Volitional

When a figure asserts supreme authority—be it a political sovereign or a deity—there are fundamentally distinct modes through which that figure may be rejected. These modes are often muddled in discourse, especially in religious debates, where disagreement is sometimes caricatured as mere obstinacy or rebellion. But upon closer inspection, we find that rejection can arise from three very different axes: epistemic rejection (lack of belief in existence), ideological rejection (disagreement with values or character), and volitional rejection (refusal of allegiance). Each operates on a separate justificatory plane: evidence, evaluation, and agency.

Understanding the distinctions and relationships among these three forms of rejection provides a more nuanced map of how individuals respond to claims of authority or divinity—and decisively refutes the idea that overwhelming evidence for a god would necessarily eliminate the freedom to reject that god.

1. Epistemic Rejection: “I Don’t Believe You Exist”

Epistemic rejection is grounded in the standards of rational belief. It occurs when a person withholds belief in the existence or identity of a proposed entity due to insufficient evidence. A reasonable skeptic confronted by someone claiming kingship might ask, “Where is your crown? Your royal lineage? Institutional backing?” Absent compelling justification, the response is clear: “I don’t believe you.”

This form of rejection is not hostile. It is rooted in evidential insufficiency and epistemic humility—the suspension or denial of belief until the evidentiary burden is met. It operates entirely within the cognitive domain of justified belief formation.

Syllogism 1: Epistemic Rejection

P1: Rational belief should be proportioned to the strength of available evidence.

P2: The evidence for the entity’s existence or identity is insufficient.

Conclusion: Therefore, one should reject the claim epistemically.

This is the position of the evidentialist and of most non-theists: rejection not out of spite, but due to the failure of the claim to meet rational standards.

2. Ideological Rejection: “I Believe You Exist, But I Disagree With You”

Ideological rejection begins after epistemic assent. One accepts that the figure exists and may even possess great power or authority—but then rejects the figure’s values, character, or teachings. The being is seen not as non-existent, but as unworthy.

This is the realm of the axiological atheist, who asserts:

“Not only do I lack belief in such a god (epistemic rejection), but even if that god did exist, I would reject Him on grounds of character, values, or conduct.”

This is not hypothetical in the sense of being merely speculative. It is conditional in the same way that ethical standards are conditionally applied: “If such a being exists, then I judge it by criteria of value and justice.” That judgment may result in rejection, regardless of epistemic certainty.

Syllogism 2: Ideological Rejection (Conditional Form)

P1: If a being exists and displays values that are unjust, cruel, or unworthy, it is rational to reject that being ideologically.

P2: If the God of classical theism existed, He would display such values (e.g., genocide, eternal torment, arbitrary favoritism).

Conclusion: Therefore, if that God existed, it would be rational to reject Him ideologically.

Importantly, this form of rejection remains valid even if epistemic rejection becomes untenable. That is, even if God’s existence were established beyond doubt, rejection on evaluative grounds remains a live and justifiable stance.

3. Volitional Rejection: “I Believe and Understand, But I Still Say No”

Volitional rejection is an act of personal agency. It is the refusal to obey, worship, or align—even when belief and even agreement exist. A person may affirm a god’s existence and even accept that the god’s values are generally sound, but still refuse allegiance out of personal autonomy, resentment, lack of trust, or defiant self-determination.

In theological narratives, this is the posture ascribed to Satan: he knows God, may understand God’s power and wisdom, but refuses submission. The Christian trope of the “reprobate mind” or “suppression of the truth” projects this kind of rejection onto atheists—but often mistakenly, since many atheists simply lack belief and are operating on epistemic or ideological grounds.

Nevertheless, volitional rejection remains conceptually distinct. It does not depend on disbelief or disagreement. It is a decision of the will.

Syllogism 3: Volitional Rejection

P1: A person can rationally choose to reject authority even when they believe in and understand that authority.

P2: Belief and understanding do not necessitate submission or allegiance.

Conclusion: Therefore, one can rationally reject a god volitionally, even if epistemic and ideological rejection are absent.

This syllogism demonstrates that free will remains intact even in the face of overwhelming evidence. The presence of incontrovertible evidence for God’s existence does not eliminate the capacity for ideological disapproval or for volitional non-submission.

4. Mapping the Modal Space of Rejection

The three types of rejection can be organized not hierarchically, but dimensionally—each independent but often co-occurring. Here is a functional map:

| Belief Status | Value Alignment | Willingness to Submit | Rejection Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denies existence | N/A | N/A | Epistemic only |

| Affirms existence, disapproves values | No | No | Ideological + Volitional |

| Affirms existence, agrees with values | Yes | No | Volitional only |

| Affirms existence, agrees, submits | Yes | Yes | None (acceptance) |

This shows clearly that ideological and volitional rejection remain active options even when epistemic rejection is precluded. One does not cease to be free merely because one is informed.

Closing Thoughts: Rejection Beyond Disbelief

Understanding the landscape of rejection—epistemic, ideological, and volitional—disentangles three very different modes of dissent that are often flattened into accusations of “denial” or “rebellion.” Each has its own structure of justification and its own ethical weight.

The axiological atheist, in particular, serves as a case study in the intersection of these categories. This person withholds belief due to lack of evidence (epistemic), but also pre-commits to rejection should that god exist and display repugnant values (ideological). Such a person retains the right, were epistemic doubts resolved, to reject volitionally as well—simply on the grounds of unwillingness to submit to an authority they regard as unworthy, regardless of its existence or power.

Thus, even if a god were to reveal itself with overwhelming clarity—removing all space for epistemic rejection—this would not nullify the free will to reject on ideological or volitional grounds. The human capacity to evaluate, judge, and disobey remains intact, and so too does the burden of any deity to be not only believed in, but found worthy and freely chosen.

Leave a comment