Consider the Following:

Summary: This post challenges the assumption that a universe without objective morality necessitates a moral lawgiver, emphasizing that humans can thrive through compassion, empathy, and cooperative behavior. It argues that societies and individuals can function harmoniously without invoking morality, as evidenced by both human psychology and the success of secular cultures.

Imagine a universe completely devoid of objective morality. Would such a world compel humans to descend into chaos or predatory behavior? The answer is not as straightforward as some claim. The absence of objective moral standards does not inherently dictate that humans must act as predators rather than as cooperative and empathetic beings. Human behavior, as it has evolved, is influenced not just by philosophical notions of morality but by a combination of social instincts, empathy, and pragmatic cooperation.

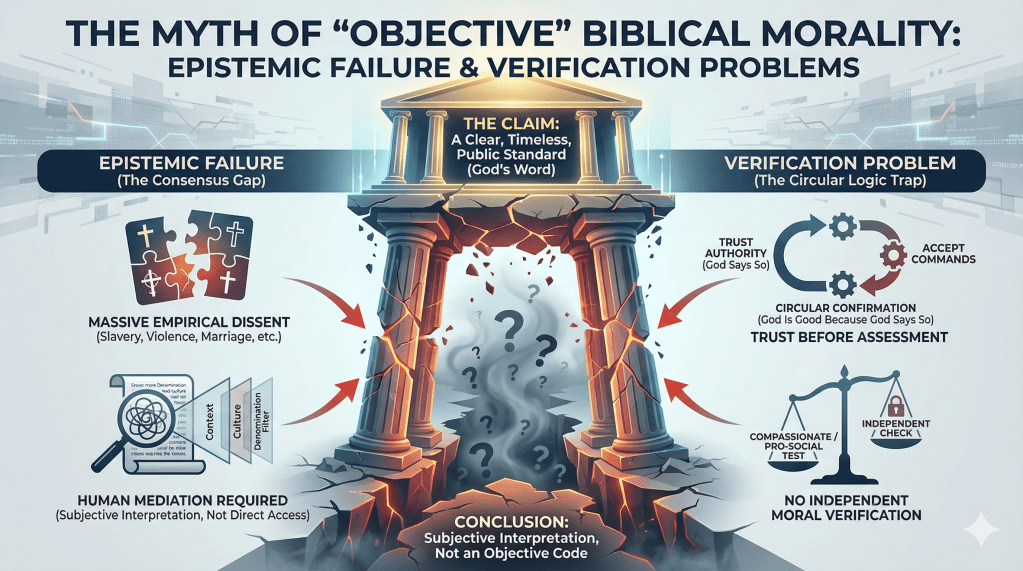

The False Dilemma: Morality vs. Absurdity

Christian apologists often argue that a universe without objective morality would be an emotionally unbearable and logically incoherent place, and from this emotional aversion, they infer the necessity of a moral lawgiver. However, this argument rests on a false dilemma: either there is objective morality, or the universe is absurd. But is this dichotomy valid? Does the emotional dissatisfaction with a lack of moral absolutes logically necessitate their existence? Emotions, while important to human experience, do not dictate the fundamental nature of reality.

To expand, consider the proposition that the absence of objective morality could simply reflect an amoral universe, one that does not care about human preferences or values. This neutral perspective on morality aligns with scientific observations: the universe operates under the principles of physics, chemistry, and biology, without apparent regard for human notions of morality. Humans, as conscious beings, have developed behavioral frameworks and norms through cultural evolution, but these are contingent, not universal absolutes.

Compassion and Empathy as Sufficient Guides

Many argue that without objective morality, humanity would spiral into unchecked selfishness and harm. Yet this overlooks the profound influence of compassion and empathy in guiding behavior. Compassion and empathy are deeply ingrained in human psychology and serve as powerful motivators for altruistic action. In fact, individuals who act out of genuine care and understanding for others often demonstrate more consistent prosocial behavior than those acting under rigid adherence to a prescribed moral code.

Consider this question: Which is more admirable—treating others well out of obligation or out of sincere compassion? Treating others kindly because of fear of divine retribution or societal judgment might ensure compliance, but it lacks the depth and authenticity of actions driven by empathy and understanding.

Counterexamples from Societal Observations

To evaluate the claim that objective morality is necessary for societal harmony, we can look to cultures and nations with minimal emphasis on belief in a universal moral code. Scandinavian countries and Japan, for instance, are notable for their low crime rates and high levels of social trust, despite widespread secularism and skepticism toward objective moral claims. By contrast, nations with strong assertions of objective morality often face significant societal challenges, including corruption and violence.

This comparison suggests that belief in objective morality is neither a prerequisite nor a reliable predictor of moral behavior. Instead, societal outcomes are more strongly correlated with factors such as education, economic stability, and social equality.

The Role of Evolutionary Psychology

Human beings are not blank slates; our behaviors are influenced by evolutionary mechanisms that favor cooperation and altruism. Traits such as reciprocity, kin selection, and group cohesion have been naturally selected because they enhance survival. Even in the absence of objective moral truths, these evolutionary tendencies would continue to promote behaviors that foster group stability and individual well-being.

For example, humans are biologically predisposed to feel guilt when harming others and joy when helping. These emotions serve as internal regulators of behavior and can function independently of any belief in objective moral laws. In this sense, morality can be understood as an emergent property of social and psychological processes rather than a divinely mandated construct.

Assessing Leadership and Individual Morality

Some critics argue that the absence of objective morality has led to atrocities committed by figures like Stalin or Hitler, who rejected religious moral frameworks. However, such examples are not representative of broader human behavior. Leaders who commit atrocities often rise to power through manipulation, narcissism, or sociopathy, traits that are unrelated to their belief or disbelief in moral absolutes.

More instructive are the behaviors of ordinary individuals in secular societies. Studies consistently show that non-believers are just as likely—if not more so—to engage in charitable acts and pro-social behavior as their religious counterparts. Moreover, these acts are often motivated by empathy rather than fear of punishment or hope for reward.

Rethinking the Argument: Premises and Conclusion

- Premise 1: If there were no objective moral realm, humans could still exhibit compassion and empathy, which are sufficient to guide behavior.

- Premise 2: Societies without belief in objective morality can and do function effectively, often with greater social harmony than those with strong beliefs in objective morality.

- Premise 3: Emotional dissatisfaction with a world lacking objective morality does not logically necessitate the existence of objective moral laws.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the absence of objective morality does not lead to absurdity, nor does it require the existence of a moral lawgiver.

The Path Forward: Embracing a Rational Approach to Human Behavior

A world without morality is not inherently absurd. Humans have the tools—compassion, empathy, and rationality—to construct and encourage systems of behavior that promote well-being and reduce harm. By embracing these tools, we can foster a society where actions are guided not by fear or obligation but by genuine care for others.

Far from being bleak, such a world holds the potential for profound authenticity and mutual respect. It challenges us to take responsibility for our actions, not because we are commanded to, but because we recognize their impact on others and on ourselves. This, perhaps, is the ultimate test of human maturity: to live harmoniously not out of compulsion but out of a deeply felt commitment to the shared human experience.

The Logical Form

1. Compassion and Empathy as Sufficient Guides

- Premise 1: If compassion and empathy exist, they can guide ethical behavior independently of objective moral laws.

- Premise 2: Human psychology is deeply influenced by compassion and empathy, which encourage altruistic behavior.

- Conclusion: Therefore, compassion and empathy are sufficient to guide ethical behavior, even in the absence of objective morality.

2. Emotional Dissatisfaction Does Not Imply Necessity

- Premise 1: Humans may feel emotionally dissatisfied with the idea of a universe lacking objective morality.

- Premise 2: Emotional dissatisfaction with a concept does not logically necessitate that the concept is real or required.

- Conclusion: Therefore, emotional dissatisfaction with a universe lacking objective morality does not necessitate the existence of a moral lawgiver.

3. Societies Without Objective Morality Can Thrive

- Premise 1: Societies with minimal belief in objective morality (e.g., Scandinavian countries and Japan) exhibit high levels of social trust and low crime rates.

- Premise 2: Societal outcomes correlate more strongly with factors like education, economic stability, and social equality than with belief in objective morality.

- Conclusion: Therefore, societies without belief in objective morality can function and thrive effectively.

4. Evolutionary Psychology Favors Cooperation

- Premise 1: Human behavior is shaped by evolutionary mechanisms that promote reciprocity, kin selection, and group cohesion.

- Premise 2: These mechanisms encourage cooperation and altruism, regardless of belief in objective morality.

- Conclusion: Therefore, evolutionary psychology provides a natural foundation for cooperative and altruistic behavior, making objective morality unnecessary.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Is a Moral Lawgiver Necessary for a Functional Universe?

CHRIS: Without a moral lawgiver, how can there be any true sense of right and wrong? Wouldn’t the universe descend into chaos if humans were left to their own devices?

CLARUS: I think the question assumes too much. First, the absence of a moral lawgiver doesn’t mean humans lack compassion or empathy—qualities deeply rooted in our psychology and evolution. These traits guide cooperative and altruistic behaviors effectively, without invoking absolutes.

CHRIS: But isn’t that subjective? If there’s no universal standard, how can we ensure people won’t act purely out of self-interest?

CLARUS: The fear of unchecked self-interest overlooks the evidence. Humans are social creatures whose survival has long depended on cooperation. Societies like those in Scandinavia and Japan, which don’t heavily rely on belief in a moral lawgiver, demonstrate higher levels of trust and lower crime rates. Clearly, humans are capable of living harmoniously without external mandates.

CHRIS: Perhaps, but doesn’t the emotional discomfort people feel when imagining a world without objective morality suggest there’s something essential about it?

CLARUS: Emotional discomfort isn’t evidence of necessity. Just because the idea of a universe without absolutes feels unsettling doesn’t mean such absolutes exist. The universe operates independently of our emotions. Our task is to build systems of rational cooperation grounded in what fosters well-being, not what feels comforting.

CHRIS: Without absolutes, though, how do we account for the atrocities committed by figures like Stalin? Doesn’t this show the dangers of rejecting the idea of a moral lawgiver?

CLARUS: Atrocities committed by leaders often stem from their narcissism or sociopathy, not their philosophical stance on absolutes. Meanwhile, the average non-believer is just as likely—if not more so—to act kindly and ethically as their religious counterparts. The behavior of ordinary people, not extreme figures, tells us more about human nature.

CHRIS: Still, without a universal standard, how do we prevent people from justifying harm?

CLARUS: Humans have evolved instincts like reciprocity and empathy, which promote cooperation and discourage harm. These natural tendencies make external absolutes redundant. Additionally, people driven by genuine care tend to act more authentically than those motivated by fear of punishment or hope for reward.

CHRIS: But what about building a functional society? Doesn’t it require a framework rooted in something beyond human emotions?

CLARUS: Societies thrive when guided by rational ethics, not absolutes. By using reason, compassion, and shared goals, we can construct systems that reduce harm and promote well-being. This isn’t hypothetical—modern secular societies already demonstrate this effectively.

CHRIS: So, you’re saying a universe without a moral lawgiver isn’t absurd?

CLARUS: Precisely. A world without absolutes isn’t absurd; it’s an opportunity for humans to take responsibility for their actions and relationships. Far from being bleak, it’s a chance to foster cooperation and genuine care based on what truly benefits humanity, rather than external mandates.

See also:

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

1. The Compass Analogy: Guidance Without Absolutes

A compass points north, but it doesn’t dictate the exact path you take to your destination. Similarly, compassion and empathy act as internal compasses for human behavior. They provide direction—promoting cooperation and well-being—without requiring the existence of absolute coordinates like a moral lawgiver. Just as travelers navigate successfully without a rigidly fixed route, humans can live harmoniously by following innate social instincts, rather than relying on external absolutes.

2. The Language Analogy: Rules Without a Single Authority

Languages develop and evolve naturally over time, guided by usage and context, not by a single ultimate authority. Grammar rules emerge from collective agreement, yet communication thrives without an all-powerful linguist dictating them. Similarly, human societies create behavioral systems through shared experiences, shaped by compassion, empathy, and rational cooperation. These systems don’t require a universal enforcer to function effectively, just as languages don’t need a central authority to flourish.

3. The Garden Analogy: Flourishing Through Natural Tendencies

A garden grows lush and vibrant when its natural elements—water, sunlight, and nutrients—are balanced, not because a gardener imposes absolute rules. In the same way, human behavior thrives when compassion and empathy are nurtured. These inherent tendencies act like the nutrients and sunlight for cooperation and altruism, enabling people to flourish without requiring a moral lawgiver, just as a garden can thrive without constant interference.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Response: Compassion and Empathy Are Insufficient Without Absolutes

Theologians might argue that compassion and empathy are subjective and can vary widely between individuals and cultures. Without an absolute standard, people could justify harmful actions by redefining what compassion means in their context. For example, oppressive regimes have claimed to act compassionately for the “greater good,” but without a universal measure, these claims cannot be objectively refuted.

2. Response: Emotional Discomfort Reflects Innate Knowledge

Theologians could assert that the emotional discomfort humans feel when contemplating a universe without objective morality stems from an innate recognition of a higher, transcendent standard. This discomfort might be viewed as evidence that humans are “wired” to seek alignment with a moral lawgiver, suggesting that such a being exists.

3. Response: Secular Societies Still Benefit from Theistic Foundations

Theologians might claim that secular societies like those in Scandinavia and Japan still operate on social frameworks originally rooted in religious traditions. While these nations may appear secular now, their historical moral systems, informed by theistic influences, continue to shape societal norms and laws. Without these foundational principles, they argue, societal cohesion might eventually erode.

4. Response: Evolutionary Psychology Lacks Prescriptive Power

Theologians could critique the reliance on evolutionary psychology by pointing out that it explains how behaviors might develop but doesn’t prescribe what behaviors humans ought to follow. Evolutionary mechanisms may promote reciprocity and cooperation, but they also account for traits like selfishness and violence. Without an external standard, there’s no rational basis to favor one evolutionary tendency over another.

5. Response: Atrocities Reflect Human Sinfulness

Theologians might counter that atrocities committed by leaders like Stalin or Hitler illustrate the dangers of rejecting a higher moral authority. They argue that such leaders, devoid of accountability to a moral lawgiver, succumbed to their own egotistical impulses. This reflects not just sociopathy but a deeper flaw in humanity that requires divine guidance to overcome.

6. Response: Rational Ethics Are Vulnerable to Relativism

Theologians could challenge rational ethics, arguing that they are inherently vulnerable to relativism. Without a universal benchmark, rationality can be used to justify vastly different ethical systems, some of which might condone harm or exploitation. They might contend that only a transcendent standard, grounded in a moral lawgiver, can provide the stability necessary for truly universal ethical principles.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “Compassion and Empathy Are Insufficient”

Compassion and empathy are indeed subjective, but this subjectivity does not preclude them from being effective guides for cooperative behavior. Social contracts, laws, and cultural norms arise from collective human experiences, evolving pragmatically to reduce harm and enhance well-being. While compassion can be misused rhetorically, shared human experiences and reasoned dialogue provide checks against harmful redefinitions. For example, secular frameworks like human rights declarations demonstrate that shared values can create stable and robust ethical systems without requiring absolutes.

2. Response to “Emotional Discomfort Reflects Innate Knowledge”

The feeling of discomfort in a world without absolutes can be explained by evolutionary psychology rather than being evidence of an external moral realm. Humans evolved to seek patterns and meaning, as these tendencies enhance survival. The discomfort likely arises from confronting existential uncertainty, not from an innate knowledge of absolutes. Additionally, emotions cannot serve as evidence of an external reality; many people feel equally strong emotions about concepts that are demonstrably false (e.g., superstitions).

3. Response to “Secular Societies Still Benefit from Theistic Foundations”

While it is true that some behavioral norms in secular societies may have historical ties to religious traditions, these societies have adapted and refined these norms independently of their theistic origins. For instance, concepts like equality and freedom have evolved significantly beyond their initial theological frameworks, often in opposition to restrictive religious doctrines. The sustained success of secular behavioral frameworks demonstrates that their functionality does not depend on the continued belief in a moral lawgiver.

4. Response to “Evolutionary Psychology Lacks Prescriptive Power”

Theologians are correct that evolutionary psychology describes behavior rather than prescribing it. However, prescriptions (social or legal, not “moral”) do not require absolutes; they can emerge from shared human goals such as reducing harm and promoting well-being. Rational agents can agree on principles that work pragmatically to achieve these goals. For instance, reducing violence and fostering cooperation are universally beneficial, even in the absence of absolutes, because they align with shared interests.

5. Response to “Atrocities Reflect Human Sinfulness”

Atrocities committed by leaders like Stalin or Hitler were more influenced by narcissism, political ideology, and authoritarian structures than by the absence of belief in a moral lawgiver. Additionally, many atrocities have been committed by religious leaders or under religious justifications, showing that belief in absolutes does not prevent such acts. A better measure of human behavior is found in the actions of the average individual, where secular societies consistently demonstrate high levels of cooperation and altruism.

6. Response to “Rational Ethics Are Vulnerable to Relativism”

While rational ethics (better referred to as “behavioral norms”) may allow for variation, this is a strength rather than a weakness. Such systems of pro-social behavior can adapt to cultural and historical contexts while maintaining core principles of reducing harm and enhancing well-being. This adaptability avoids the rigidity of absolutes, which can become oppressive or outdated. Shared human interests and reasoned discourse serve as effective safeguards against harmful relativism, as evidenced by international agreements on issues like human rights and environmental protection.

Note on the Absence of a Moral Realm

It is essential to clarify that the arguments provided above do not affirm the existence of a moral realm or any framework in which moral facts actually reside. The concept of morality itself does not need to exist as an objective or external reality for humans to construct and experience a civil society.

Human behavior, social cohesion, and cooperative frameworks can emerge entirely from shared goals, pragmatic agreements, and natural tendencies like compassion, empathy, and rational thought. These tools are sufficient to foster societal well-being, promote cooperation, and reduce harm without invoking or assuming the existence of an actual moral realm in which moral facts reside.

Clarifications

The Baseless Fear of a World Without a Moral System

A world without a moral system often evokes unease, driven by the perception that chaos and selfishness would prevail. Many assume that without an external structure dictating behavior, individuals would default to harmful actions. However, this fear is not grounded in evidence but in a misunderstanding of human nature and society’s reliance on empathy, compassion, and cooperation—qualities that exist independently of any moral framework. A closer examination reveals that not only is a world without a moral system possible, but compassion, as a guiding principle, can often outperform moral systems even when evaluated by their own metrics of success.

Lessons from the Animal Kingdom

The behavior of non-human animals offers a compelling counterpoint to the fear of a world without a moral system. Animals, devoid of codified rules or moral structures, frequently exhibit behaviors that foster cohesion and mutual survival.

- Wolves rely on intricate social hierarchies and cooperative hunting strategies that benefit the pack as a whole. Their survival hinges not on individual selfishness but on group solidarity.

- Bonobos, our closest relatives in the animal kingdom, are known for resolving conflicts through affectionate behaviors rather than aggression, demonstrating that social harmony can arise from instincts rather than imposed systems.

- Elephants show remarkable empathy, assisting injured herd members and mourning their dead. Their cooperative behavior is driven by intrinsic bonds, not by an external moral code.

These examples illustrate that cohesive, harmonious living is not unique to humans and does not require a moral system. Instead, it arises from natural tendencies toward cooperation and compassion.

Compassion as the Superior Guide

Compassion, an innate human quality, has a profound ability to guide behavior in ways that align with societal well-being. Unlike rigid moral systems, which often rely on arbitrary rules or external authorities, compassion emerges from a genuine concern for others and a desire to alleviate suffering. This makes it both more flexible and more authentic as a guiding principle.

- Compassion Is Intrinsically Adaptive: Moral systems tend to impose universal rules that may fail to account for context. Compassion, however, adapts to individual circumstances, promoting actions that are situationally appropriate. For example, providing food to a starving person is an act of compassion that transcends moral debates about ownership or entitlement.

- Compassion Outperforms Metrics of Success: Even when measured against the goals of moral systems—such as reducing harm or promoting justice—compassion excels. A compassionate approach naturally avoids harm because it prioritizes the well-being of others. In contrast, moral systems often justify harm through rigid adherence to principles (e.g., punitive justice systems that neglect rehabilitation).

- Compassion Is More Inclusive: Moral systems frequently delineate insiders and outsiders, offering preferential treatment to members of specific groups. Compassion, by contrast, recognizes the shared humanity of all individuals, fostering inclusivity and reducing conflict.

Dispelling the Fear of Chaos

The fear of chaos in a world without a moral system is rooted in the assumption that humans are inherently selfish or destructive. However, this perspective ignores the evolutionary and social mechanisms that have shaped human behavior.

Humans, like many social animals, have evolved to prioritize cooperation because it enhances group survival. Traits such as reciprocity, trust, and altruism are not byproducts of moral systems but foundational elements of human nature. Even in the absence of a moral framework, these traits ensure that societies remain cohesive and functional.

Additionally, modern secular societies demonstrate that robust social structures can exist without reliance on moral absolutes. Countries with high levels of secularism and emphasis on human rights, such as Sweden and Norway, consistently rank among the most peaceful and equitable in the world. These examples prove that societal success does not depend on adherence to a moral system but on pragmatic cooperation and shared values.

Compassion Beyond Morality

Critically, compassion is not only sufficient but often superior to moral systems because it operates on the level of human connection, not abstract rules. Where moral systems falter—becoming rigid, exclusionary, or outdated—compassion remains relevant, adapting to the needs of individuals and communities.

Moreover, compassion’s effectiveness is not theoretical; it is demonstrable in everyday life. Acts of kindness, generosity, and understanding frequently solve conflicts and promote well-being in ways that moralistic approaches cannot. For example, a compassionate response to poverty—addressing its root causes—outperforms punitive moral judgments about the behavior of those in poverty.

A World Without Fear

A world without a moral system is not a dystopian nightmare but an opportunity to embrace a more authentic and humane approach to living. Compassion, as a guiding principle, offers the flexibility, inclusivity, and effectiveness that moral systems often lack.

The fear of such a world is baseless because it overlooks the inherent capacities of humans and other social creatures to build harmonious societies. By focusing on shared humanity, rather than rigid principles, we can achieve a world that is not only civil but profoundly connected and flourishing.

The Erosion of Compassion in the Pursuit of a Universal Moral System

The aspiration for a universally enforced and accepted moral system is often born from a desire to bring order and coherence to human behavior. However, history demonstrates that such systems frequently come at a significant cost: the erosion of compassion. When rigid rules and external authority take precedence, individuals may sacrifice empathy and genuine concern for others in favor of blind adherence to a prescribed standard. The tragic story of the Israelite soldiers ordered to kill Amalekite infants exemplifies this dynamic, revealing how commitment to a divine or absolute moral framework can suppress the natural instincts of compassion and empathy.

The Problem with Universally Enforced Moral Systems

At the heart of any universal moral system is a set of fixed principles that claim to transcend individual perspectives and emotions. These systems promise clarity and order but often require their adherents to override their innate instincts in favor of rigid obedience. This is particularly true when the system is linked to divine authority, where disobedience is framed as a rebellion against a higher power.

- Suppressing Individual Judgment: Universal moral systems demand that personal compassion be subordinated to the “greater good” as defined by the system. For example, an individual might feel empathy for an enemy combatant but suppress this feeling if the system mandates their execution as a moral duty.

- Dehumanizing the “Other”: These systems frequently delineate insiders and outsiders, labeling the latter as unworthy of compassion. This dehumanization facilitates actions that would otherwise be unthinkable, as adherents justify harm as necessary to uphold the system’s standards.

- Prioritizing Rule Adherence Over Empathy: In universal moral systems, the focus shifts from understanding others to fulfilling obligations. Compassion, being situational and flexible, is often viewed as a weakness or distraction in the face of rigid moral imperatives.

The Israelite Soldiers and the Amalekites: A Case Study

The biblical story of the Israelites’ war against the Amalekites (1 Samuel 15:3) illustrates the dangers of universal moral systems tied to divine authority. According to the text, the Israelite soldiers were commanded by their God to “destroy the Amalekites—men, women, children, and infants.” This command was presented as a moral duty, justified by the Amalekites’ past transgressions against the Israelites.

From a modern perspective, this directive is horrifying. How could soldiers carry out such an order, particularly against infants, who are innocent by any rational standard? The answer lies in their commitment to a moral system that placed divine commands above all else.

- Moral Justification Over Compassion: The soldiers likely suppressed their natural compassion for the Amalekite children because their moral framework framed the act as just. They believed their God’s authority validated actions that, under normal circumstances, would be unthinkable.

- Dehumanization of the Amalekites: By portraying the Amalekites as enemies of God, the moral system stripped them of their humanity in the eyes of the Israelites. This dehumanization made it easier for the soldiers to carry out the atrocities without guilt.

- Fear of Divine Repercussions: In such systems, disobedience to moral commands often carries severe consequences. The soldiers may have feared punishment or divine wrath more than they trusted their own compassionate instincts.

Compassion Versus Morality

Compassion, as a flexible and context-sensitive guide to behavior, directly conflicts with the rigidity of universal moral systems. While moral systems impose one-size-fits-all rules, compassion considers the nuances of each situation, prioritizing the well-being of those involved over adherence to abstract principles.

- Compassion Humanizes: Unlike universal moral systems, which often dehumanize those outside their scope, compassion recognizes the shared humanity of all individuals. A compassionate Israelite soldier might have refused to kill an Amalekite child, not because of a moral rule, but because of an instinctive recognition of the child’s innocence.

- Compassion Seeks Connection: Universal moral systems often focus on separation—good versus evil, insider versus outsider. Compassion, on the other hand, seeks connection, fostering understanding and reducing harm.

- Compassion Adapts: Moral systems are rigid and struggle to accommodate complex situations. Compassion, being rooted in empathy, adapts to context, allowing for responses that better align with human well-being.

The Consequences of Suppressing Compassion

History is replete with examples of atrocities committed in the name of universal moral systems. From religious crusades to ideological purges, the pursuit of moral universality has frequently led to violence, oppression, and suffering. The common thread in these events is the devaluation of individual compassion in favor of adherence to rules or doctrines.

The story of the Israelite soldiers demonstrates this vividly. Their actions, horrifying by modern standards, were justified by their moral system. Yet the absence of compassion in their deeds left a legacy of violence and dehumanization that continues to challenge us to this day.

A Better Path Forward: Compassion Without a Moral System

The antidote to the failures of moral systems is not the imposition of another rigid framework but the embrace of compassion as the guiding principle for human behavior. Unlike moral systems, compassion is adaptable, inclusive, and deeply human. It allows for the complexities of life, fostering understanding and connection rather than division and violence.

In a world guided by compassion, the story of the Amalekite infants would unfold differently. Rather than adhering to a command to kill, the soldiers would recognize the humanity of their supposed enemies and act in ways that reduce suffering and promote mutual well-being. Compassion, far from being a weakness, would prove itself as the superior guide to action, capable of fostering a world that is not only civil but profoundly humane.

Leave a comment