Consider the Following:

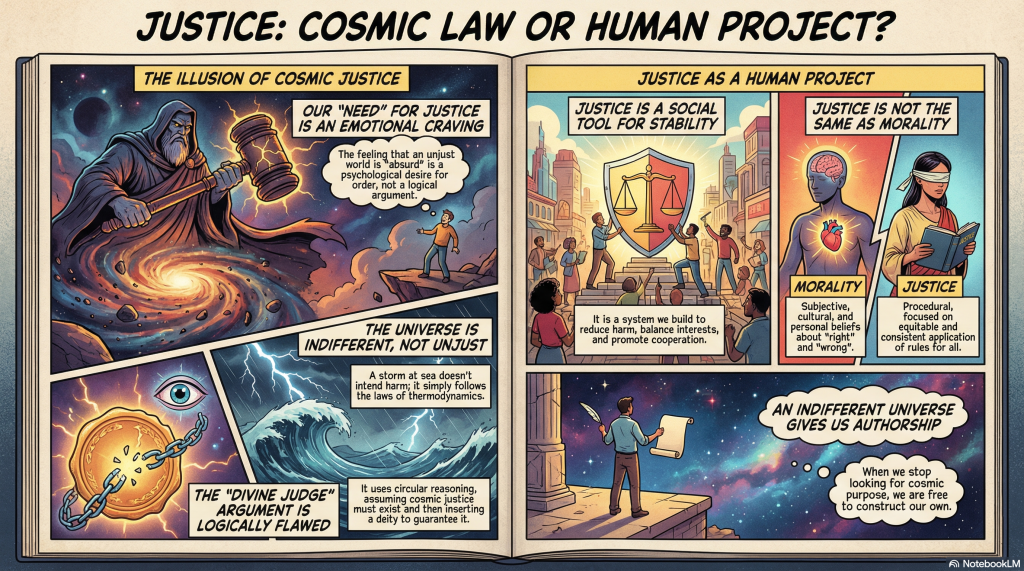

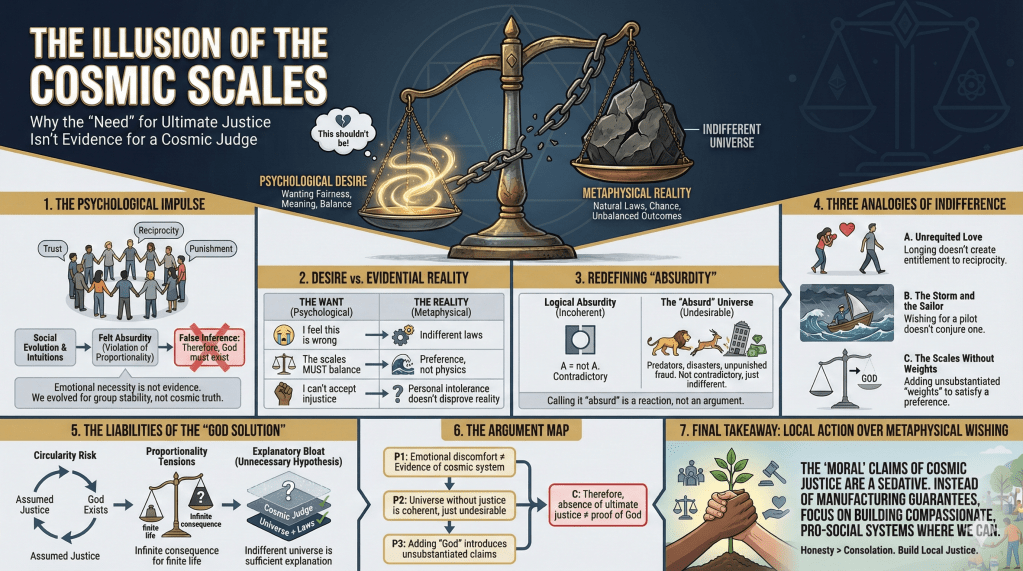

Summary: This article argues that the absence of ultimate justice in the universe does not logically imply the existence of a God of justice, as emotional discomfort is insufficient evidence for such a conclusion. It emphasizes the importance of intellectual honesty in confronting an indifferent universe without resorting to emotionally prompted assumptions.

Imagine a universe devoid of ultimate justice—a reality in which heinous acts often go unpunished, and acts of selflessness are not rewarded beyond the immediate social sphere. While this scenario may seem emotionally unsettling, does its perceived absurdity justify belief in a divine arbiter to ensure ultimate justice? Or is the discomfort merely a reflection of our emotional biases rather than a clue to some ultimate truth?

To answer this question rigorously, we must untangle the emotional appeal from the logical structure of the argument and critically assess whether the notion of ultimate justice is a necessity or merely a consolation.

Emotional Appeals Do Not Establish Truth

One of the most pervasive mistakes in reasoning is allowing emotional unease to dictate beliefs about reality. While the longing for cosmic justice—a universal reckoning that aligns outcomes with merit—feels compelling, feelings alone are not reliable indicators of objective truths. Consider the following:

- Desires and Reality Are Not Synonymous: Human experience is replete with desires that do not correspond to reality. For example, an unrequited love does not imply a cosmic injustice, nor does it demand the existence of a higher being to ensure fairness. Similarly, our indignation at unchecked injustices does not imply a system of ultimate justice exists beyond our world.

- Fallibility of Emotional Reasoning: Emotions are valuable in motivating actions but are often ill-suited for determining the nature of external reality. Consider emotions like jealousy or infatuation, which frequently distort clear thinking. Just as these emotions can lead to flawed conclusions (“They belong to me because I feel jealous”), so too can our yearning for ultimate justice lead us to assume a divine judge.

The logical leap from emotional unease to the assertion of a divine arbiter is not only unwarranted but risks introducing significant biases into our reasoning.

A Universe Without Ultimate Justice Is Not Absurd

The claim that a universe without ultimate justice is “absurd” reflects an emotional discomfort, not a logical contradiction. Absurdity implies a violation of reason or coherence. However, a world where justice is incomplete or nonexistent is neither illogical nor incoherent—it is simply a world where human desires are not universally fulfilled. Consider:

- Neutrality of the Universe: The natural world is indifferent to human concepts like fairness or justice. Earthquakes, diseases, and other natural phenomena do not reflect intentional harm but rather the neutral mechanics of the physical universe. To project human notions of justice onto the cosmos is anthropocentric and unwarranted.

- Justice as a Social Construct: Justice, in its practical form, arises from human societies as a means to foster cooperation, reduce harm, and maintain order. It is neither universal nor eternal but contingent upon social agreements and norms. Its existence in human society does not necessitate an ultimate, cosmic counterpart.

- Existence Does Not Depend on Justice: Many aspects of life—such as love, creativity, or scientific discovery—thrive independently of any ultimate system of justice. While justice is valuable for human flourishing, its absence on a cosmic scale does not render life meaningless or absurd.

The Pitfalls of a Theistic “Solution”

Advocates of a just deity often argue that belief in God provides the only foundation for meaningful justice. However, this position faces several critical challenges:

- Circular Reasoning: Assuming the existence of a just God to address the lack of ultimate justice is circular. It presupposes the very thing it seeks to prove: that ultimate justice is necessary and must be enforced by a higher power.

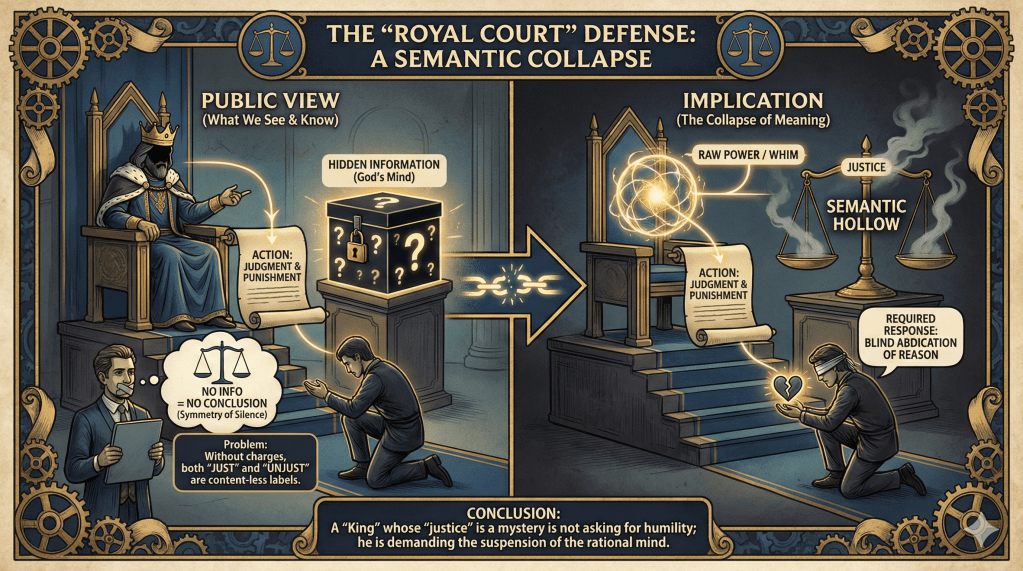

- Moral Incoherence in Theistic Justice: The concept of divine justice as depicted in many religious traditions introduces its own contradictions. For instance, the idea of eternal punishment for finite crimes, as described in certain doctrines, conflicts with our intuitive understanding of proportionality and fairness. Such a system of “justice” may be emotionally satisfying to its adherents but is logically incoherent.

- Unnecessary Hypothesis: Invoking a God of justice to resolve the absence of ultimate justice is an unnecessary addition to the explanation of the universe. According to Occam’s Razor, simpler explanations that do not multiply entities unnecessarily are preferable. A universe governed by indifferent natural laws is sufficient to explain the lack of ultimate justice without resorting to metaphysical constructs.

The True Challenge: Accepting an Indifferent Universe

The emotional discomfort with a universe lacking ultimate justice stems not from its incoherence but from its challenge to human expectations. We desire a world that aligns with our sense of fairness, yet the universe offers no guarantees. The real task is not to invent comforting beliefs but to confront reality with intellectual honesty.

- Acceptance as Strength: Accepting the universe as it is, without imposing unwarranted assumptions, demonstrates intellectual and emotional maturity. It allows us to focus on the here and now, striving to create justice where we can rather than yearning for a cosmic arbiter.

- Courage to Face Uncertainty: By acknowledging the indifference of the universe, we liberate ourselves from the need for ultimate explanations and open ourselves to the richness of human experience as it unfolds.

Conclusion

The perceived absurdity of a universe without ultimate justice is not a valid argument for the existence of a God of justice. Emotional discomfort and the longing for fairness do not constitute evidence of a higher power that might dispense ultimate justice. Instead, we must recognize the limits of our emotional reasoning and embrace the reality of an indifferent universe with honesty, refusing to allow conclusions emergent of emotional discontent.

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Emotional Discomfort Does Not Establish Truth

- P1: Emotional unease with the absence of ultimate justice does not constitute evidence for the existence of such justice.

- P2: Emotions, while motivating, are unreliable tools for discerning objective reality.

- P3: Emotional reasoning often leads to flawed conclusions, as seen in examples like jealousy or infatuation.

- Conclusion: Emotional discomfort with a universe lacking ultimate justice does not logically necessitate the existence of a God of justice.

Argument 2: A Universe Without Ultimate Justice Is Not Absurd

- P1: Absurdity implies a logical contradiction or incoherence.

- P2: A universe lacking ultimate justice is neither contradictory nor incoherent; it simply fails to align with human desires.

- P3: Many aspects of existence, such as natural phenomena, operate without regard to human concepts like fairness or justice.

- Conclusion: The absence of ultimate justice in the universe does not make it absurd.

Argument 3: Belief in a God of Justice Introduces Logical Problems

- P1: Assuming a God of justice to resolve the discomfort of incomplete justice presupposes the very thing it seeks to prove.

- P2: Religious depictions of divine justice often contain internal contradictions, such as the disproportionate nature of eternal punishment for finite offenses.

- P3: Invoking a God of justice is an unnecessary hypothesis when simpler explanations, such as the indifference of natural laws, suffice.

- Conclusion: The concept of a God of justice introduces logical inconsistencies and is not required to explain the absence of ultimate justice.

Argument 4: An Indifferent Universe Is Intellectually Honest

- P1: The universe operates according to natural laws that are indifferent to human concerns, including justice.

- P2: Accepting the universe’s indifference avoids the biases introduced by emotionally driven assumptions.

- P3: Facing an indifferent universe with intellectual honesty fosters maturity and clarity in understanding reality.

- Conclusion: Accepting the indifference of the universe without invoking unwarranted assumptions is a more intellectually honest position than assuming the necessity of ultimate justice.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Ultimate Justice

CHRIS: Doesn’t the absence of ultimate justice make the universe absurd? If there’s no God ensuring justice, people like Hitler or Stalin could escape consequences entirely. Surely that means a just God must exist.

CLARUS: Not necessarily, Chris. Absurdity refers to a logical contradiction or incoherence, not merely an emotional reaction of dissatisfaction. A universe lacking ultimate justice is entirely coherent; it simply fails to meet our desires for fairness. Moreover, natural phenomena like earthquakes or diseases are indifferent to concepts like justice, yet we do not find them absurd. The absence of ultimate justice may challenge our expectations, but it does not violate the logical consistency of the universe.

CHRIS: But don’t our emotions point to a deeper truth? Our outrage at injustice feels like a clue to the existence of a just God. Why would we have that reaction otherwise?

CLARUS: Emotions are powerful but unreliable indicators of objective reality. They often lead to distorted conclusions, as in the case of jealousy or infatuation, which can make us believe things that aren’t true. Just as jealousy doesn’t entitle someone to another person, our outrage at injustice doesn’t prove the existence of ultimate justice. Instead, emotional unease reflects our preferences and values, not evidence for a divine truth. While our feelings may motivate us to seek justice, they are not a valid basis for concluding that ultimate justice or a God of justice exists.

CHRIS: Still, wouldn’t a just God resolve the problem of injustice? If we believe in God, we can hope for justice in the afterlife even if it’s absent now.

CLARUS: That approach introduces significant logical problems. Assuming a God of justice to resolve the absence of justice presupposes the very thing you’re trying to prove, which is circular reasoning. Moreover, many religious depictions of divine justice are internally inconsistent. For instance, the idea of eternal punishment for finite crimes conflicts with our understanding of proportionality and fairness. Finally, invoking God as the solution to injustice is unnecessary when natural explanations, such as the universe’s indifference to human concerns, adequately explain the lack of ultimate justice. Rather than solving the problem, belief in a God of justice adds unnecessary contradictions.

CHRIS: If there’s no ultimate justice, doesn’t that make life meaningless? How can we find purpose without it?

CLARUS: Purpose and justice are separate issues. The universe operates according to natural laws indifferent to human concepts like justice, and accepting this indifference is not nihilistic but intellectually honest. Meaning arises from our relationships, creativity, and understanding of reality, rather than from the promise of ultimate justice. Acknowledging the absence of cosmic guarantees allows us to focus on what we can control, finding fulfillment and purpose in the here and now.

CHRIS: But doesn’t believing in God give people hope, even if you think it’s unnecessary?

CLARUS: Hope based on unsupported assumptions may feel comforting, but it compromises intellectual honesty. True hope comes from embracing reality as it is and finding strength in our ability to confront challenges without resorting to unwarranted beliefs. Accepting an indifferent universe enables us to focus on creating justice and meaning through our efforts, rather than relying on a speculative and unproven God of justice.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Unrequited Love

Imagine someone who deeply loves another person but does not have their feelings reciprocated. They may feel intense longing and even perceive this lack of mutual affection as an injustice, but their emotions do not make it true that they are entitled to the other person’s love. Similarly, the emotional discomfort we feel about injustice in the universe does not necessitate the existence of ultimate justice. Just as unrequited love is a reality many must accept, so too must we accept the universe’s indifference to human desires for fairness.

Analogy 2: The Storm and the Sailor

Consider a sailor caught in a storm at sea. The storm is indifferent to the sailor’s plight, neither intending harm nor offering mercy—it simply follows the laws of nature. While the sailor might wish for a guiding force to calm the storm, this longing does not prove the existence of such a force. In the same way, the indifference of the universe to human concerns, such as justice, reflects the natural order and not the presence of a cosmic arbiter.

Analogy 3: The Scales Without Weights

Imagine a pair of scales that have no external weights placed upon them. The scales remain balanced in their natural state, unaffected by human notions of fairness or proportion. Adding weights to tip the scales introduces unnecessary interference. Similarly, invoking a God of justice to balance perceived injustices in the universe is an unnecessary addition to an already coherent natural order. The universe’s balance exists independently of our ideas about justice or fairness.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Emotional Intuitions as Evidence

Theologians might argue that our emotional discomfort with injustice is not merely a subjective feeling but an indication of an innate moral awareness instilled by a higher power. From this perspective, emotions like outrage at injustice serve as evidence for a transcendent moral order rather than a mere byproduct of human evolution or social conditioning.

2. Absurdity and Meaning

They could contend that a universe without ultimate justice is not just emotionally unsettling but also existentially absurd. Without a divine source of justice, they may argue, the moral and ethical frameworks we rely upon lose their grounding, leaving life devoid of objective meaning or purpose.

3. Justice Beyond Human Constructs

Theologians might claim that while justice is socially constructed in part, the universal longing for justice across cultures suggests the existence of an ultimate moral lawgiver. This universal longing is proposed as evidence that ultimate justice exists and points to the nature of a divine being.

4. Logical Consistency of Divine Justice

They could argue that the notion of eternal punishment for finite crimes aligns with the theological view of offenses against an infinitely holy God. From this perspective, eternal consequences are not inconsistent but proportional to the nature of the being against whom the offense is committed.

5. Hope as a Rational Foundation

Theologians might assert that belief in a God of justice provides a rational foundation for hope, enabling individuals to strive for justice even in the face of seemingly insurmountable injustice. They could argue that this hope is not merely comforting but also inspires moral action and resilience in the human experience.

6. The Universe’s Fine-Tuning

Theologians may argue that the fine-tuning of the universe for life suggests intentionality and purpose, which is compatible with the existence of ultimate justice. They might propose that this purpose extends beyond physical parameters to include a moral dimension governed by a just God.

7. Divine Justice as Necessary for Free Will

Lastly, theologians might claim that ultimate justice ensures the meaningfulness of human free will. Without consequences beyond this life, they could argue, moral choices lose their ultimate significance, undermining the concept of freedom and responsibility. Ultimate justice, in this view, preserves the coherence of moral agency.

Counter-Responses

1. Emotional Intuitions as Evidence

While emotions like outrage at injustice might reflect deeply ingrained social or evolutionary values, they do not constitute evidence for a transcendent moral order. Emotional reactions often result from adaptive mechanisms that enhance group survival rather than pointing to objective truths. For instance, feelings of fairness help maintain social cohesion but do not necessarily imply the existence of an ultimate moral lawgiver. Without empirical evidence to support this claim, emotional intuitions remain insufficient to prove ultimate justice.

2. Absurdity and Meaning

The absence of ultimate justice does not render life devoid of objective meaning, as meaning and purpose are not contingent on external validation. Humans find profound significance in relationships, creativity, and understanding the world, none of which require a divine guarantor. The assertion conflates existential discomfort with logical incoherence, which is a category error. Ultimate meaning is a human construct, not a necessity for life to be rich with value.

3. Justice Beyond Human Constructs

The universality of the longing for justice can be explained through evolutionary psychology and cultural development, as societies thrive when fairness and cooperation are valued. This longing does not require a divine moral lawgiver but can instead reflect practical adaptations for group survival. Furthermore, cultural differences in concepts of justice challenge the claim of a universal moral order, showing that justice is highly contextual and socially derived.

4. Logical Consistency of Divine Justice

The concept of eternal punishment for finite crimes is inconsistent with proportional fairness, as it violates the principle that consequences should be commensurate with actions. Invoking an infinitely holy being as justification does not resolve this problem but shifts the inconsistency onto the nature of the deity itself. A just system would seek restoration or proportional consequences, not infinite retribution, making the theological defense logically incoherent.

5. Hope as a Rational Foundation

While hope can inspire moral action, it does not depend on belief in a God of justice. Secular frameworks provide rational foundations for hope based on human progress, cooperation, and resilience. Basing hope on unverifiable beliefs introduces a dependency on potentially false premises, which undermines intellectual honesty. Genuine hope arises from confronting reality as it is, not as we wish it to be.

6. The Universe’s Fine-Tuning

The argument from fine-tuning conflates physical constants necessary for life with evidence for ultimate justice. Even if the universe is finely tuned for life, this does not imply that it is governed by a moral dimension or a just God. Fine-tuning can be explained through natural mechanisms such as the multiverse hypothesis or the anthropic principle, both of which provide alternatives without invoking divine intentionality.

7. Divine Justice as Necessary for Free Will

The meaningfulness of free will does not require ultimate justice; moral decisions can carry significance within the temporal and social realms where their consequences are realized. Furthermore, the introduction of eternal consequences undermines true freedom, as it coerces choices through fear of infinite punishment. Free will is better understood as a capacity to make decisions based on reason and context rather than a construct dependent on a punitive or rewarding afterlife.

Clarifications

The Categorical Difference Between Morality and Justice: Equitability as the Core of Justice

While morality and justice are often treated as overlapping or interdependent, they differ categorically in their focus and application. Morality concerns subjective notions of right and wrong, often rooted in cultural, religious, or individual frameworks. Justice, by contrast, centers on the fair and consistent application of rules and the equitable treatment of individuals within a society. The key distinction lies in equitability—the objective and measurable fairness of outcomes—which serves as the cornerstone of justice, distinguishing it from the subjective domain of morality.

Morality: Subjective and Variable

Morality is primarily concerned with the intrinsic nature of actions, asking whether something is inherently right or wrong. It draws upon subjective frameworks that vary widely across cultures, individuals, and time. For example, moral norms surrounding issues like honesty, dietary restrictions, or interpersonal relationships often diverge significantly between societies, reflecting their rootedness in cultural or personal beliefs.

The variability of moral systems underscores their subjective nature. While morality seeks to provide guidance on individual behavior, its reliance on culturally contingent norms makes it unsuitable as a universal foundation for societal systems. What is “moral” in one context may be viewed as neutral—or even immoral—in another, making morality inherently relative.

Justice: Structural and Grounded in Equitability

Justice, by contrast, transcends subjective values by focusing on the equitable treatment of individuals and groups under a shared framework of rules. It evaluates whether people are treated fairly in relation to one another, emphasizing impartiality and consistency. Equitability ensures that justice operates not on moral judgments but on objectively assessable principles, such as fairness in distribution, equal access to opportunities, and proportionality in enforcement.

For example, a fair tax system would be judged not on its moral righteousness but on whether it distributes the tax burden equitably among citizens, considering factors like income, wealth, and societal contribution. Equitability allows justice to function independently of subjective moral claims, ensuring that outcomes are assessed based on their fairness rather than their alignment with specific ethical beliefs.

Equitability as the Core Metric of Justice

Justice can be objectively assessed by measuring equitability through three key dimensions:

- Equality of Opportunity: Justice systems should provide individuals with equal access to opportunities, regardless of factors like race, gender, or socioeconomic status. This dimension ensures that systemic biases or structural barriers are minimized.

- Proportionality in Consequences: Equitability requires that consequences are proportionate to actions. For instance, a justice system that imposes the same penalty for minor theft as for violent crimes fails to uphold proportional fairness.

- Consistency and Impartiality: Equitable justice ensures that rules are applied consistently across cases, without favoritism or prejudice. A predictable system fosters trust and stability, as individuals can rely on impartial enforcement of laws.

These dimensions provide objective, non-moral criteria for evaluating the fairness and functionality of justice systems, making equitability the defining characteristic of justice.

The Practical Divide: Justice Without Morality

The categorical difference between morality and justice lies in their evaluative focus. Morality concerns itself with the intrinsic “rightness” of actions, relying on subjective and culturally contingent norms. Justice, grounded in equitability, evaluates fairness objectively through measurable criteria like proportionality, consistency, and equality of opportunity. This makes justice not only distinct from morality but also independent of it.

By centering equitability, justice can be assessed and applied in a manner that transcends cultural or moral relativism. A justice system does not need to rely on moral assumptions to be fair; it achieves fairness by objectively ensuring equitable treatment and outcomes for all. This distinction is critical for building systems that prioritize societal harmony, order, and trust over subjective ethical debates.

Leave a comment