Consider the Following:

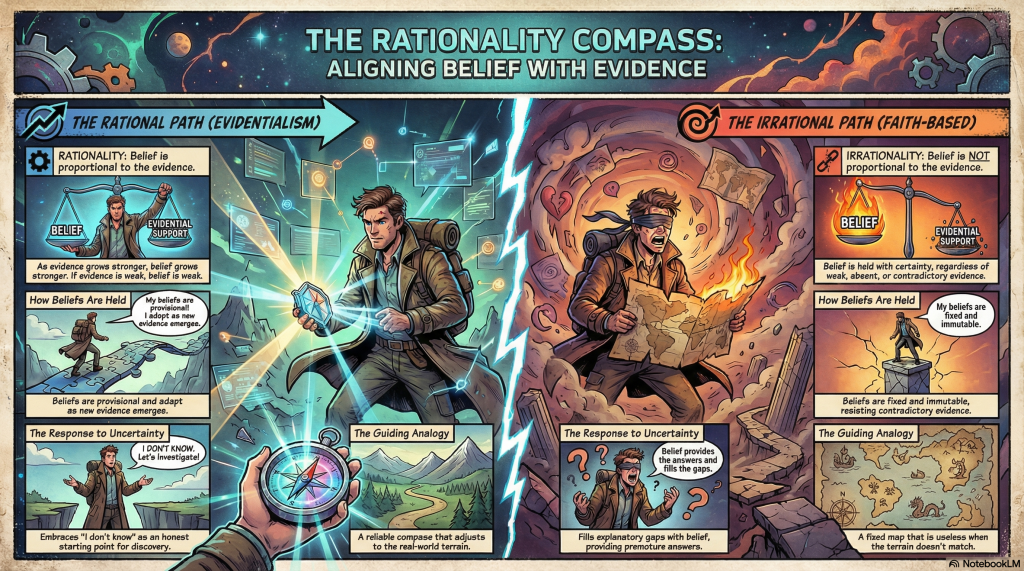

Summary: This post argues that belief should align with the evidence, rejecting faith-based ideologies that exceed or contradict the balance of confirming/disconfirming evidence. By embracing intellectual humility and prioritizing rational inquiry, individuals can navigate uncertainty while fostering adaptable and coherent worldviews.

Imagine a young man named Nick in ancient Greece. Nick embodies the principle that belief should never exceed the degree of evidence available. He rejects prevailing explanations attributing phenomena such as lightning, disease, and reproduction to the whims of the gods. When confronted by his mother, who demands to know what belief system has replaced his faith in the gods, Nick responds, “None.” She retorts, “But everyone believes in something!” Nick replies, “I believe in proportioning my belief to the evidence and reserving judgment when evidence is insufficient.”

What follows is a rigorous exploration of the key questions raised by this exchange.

Is Nick’s Commitment to Rationality an Ideology?

To describe Nick’s approach as an “ideology” risks diluting the term. An ideology typically refers to a rigid system of beliefs that shapes one’s worldview. Nick’s commitment, by contrast, is a methodological stance: beliefs must track evidence, and where evidence is lacking, belief is suspended.

Nick’s approach, often called evidentialism, stands in stark contrast to dogmatism (unquestioning adherence to beliefs) and nihilistic skepticism (denial of the possibility of knowing anything). Instead, evidentialism acknowledges the provisional nature of understanding, where beliefs evolve as evidence grows. This is not ideology; it is the antithesis of ideology—a framework for remaining ideologically unshackled.

Is Nick’s Mother’s Belief-Based Approach Reasonable?

Nick’s mother represents a widespread psychological impulse: the need to fill explanatory gaps with belief. While this inclination has evolutionary roots—early humans benefited from positing explanations for unknown phenomena—it frequently leads to superstition and premature conclusions.

Faith-based belief systems often prioritize emotional comfort over epistemic accuracy. They provide answers, but not necessarily the correct ones. By contrast, admitting uncertainty, as Nick does, is an act of intellectual humility. It places inquiry above comfort, prioritizing the search for truth over the need to appease existential anxieties.

Is It Incoherent to Say, “I Don’t Know”?

Far from incoherence, “I don’t know” is a hallmark of epistemic integrity. It signals the ability to recognize the boundary between knowledge and ignorance—a boundary that is both dynamic and necessary for discovery.

Insisting on belief where evidence is absent fosters confirmation bias: the tendency to favor information that supports one’s preexisting beliefs. In contrast, acknowledging uncertainty preserves openness to new evidence, a critical feature of rational inquiry.

“I don’t know” is not a dead end; it is an open door.

Do All Individuals Place Their Trust in Some Ideology?

Some Christian leaders assert that everyone places faith in something—whether it be God, science, or oneself. However, this argument conflates faith with confidence grounded in evidence. Trusting in the reliability of the scientific method or in reasoned inference is qualitatively different from faith, which requires belief beyond—or even contrary to—evidence.

Faith is often characterized by immutability; evidence does not sway it. By contrast, evidential commitments are inherently revisable. A belief held in proportion to evidence can shift as the evidence evolves. To equate these two forms of trust is to commit a category error.

Is It Rational to Adopt an Ideology Beyond the Evidence?

The rationality of a belief hinges on its relationship to evidence. To adopt an ideology beyond evidence is to commit to a fideistic stance—a leap of faith unsupported by reason. Such a stance is inherently precarious, for it divorces belief from the mechanisms that ensure its reliability.

This detachment leads to cognitive dissonance, where individuals experience psychological tension when confronted with evidence that undermines their beliefs. The more entrenched the ideology, the more elaborate the mental gymnastics required to reconcile it with reality.

By aligning beliefs with evidence, one avoids this epistemic instability and fosters a worldview that is both coherent and adaptable.

Is the Person Without an Ideology to Be Pitied?

On the contrary, the person who aligns beliefs with evidence is to be commended. Such individuals embody the principle of intellectual humility, recognizing that certainty without sufficient evidence is arrogance masquerading as conviction.

These individuals are not rudderless; they are guided by a compass calibrated to the real world. This compass—the commitment to proportion belief to evidence—enables them to navigate complexity without succumbing to oversimplified dogmas. They are flexible, open to correction, and equipped to thrive in a reality that resists neat categorization.

The Pitfalls of Faith-Based Epistemology

Faith-based epistemology—holding beliefs with certainty in the absence of evidence—has several drawbacks:

- Encourages Confirmation Bias: Faith tends to seek self-affirming evidence while ignoring disconfirming data.

- Discourages Questioning: Faith valorizes steadfastness, often branding doubt as a moral failing rather than a virtue.

- Inhibits Discovery: By providing premature answers, faith discourages the continued search for evidence.

Faith may offer emotional solace, but this solace often comes at the cost of intellectual stagnation.

Recognizing and Avoiding Fallacies in Ideological Debates

Some Christian leaders employ rhetorical tactics to equate rational approaches with faith-based ones. These include:

- Tu Quoque Fallacy: Accusing critics of harboring ideologies to deflect attention from their own unjustified beliefs.

- False Equivalence: Conflating evidence-based trust with faith, as though both were equally unjustified.

- Strawman Arguments: Misrepresenting skepticism as a nihilistic rejection of all belief.

Such fallacies obscure the substantive differences between rational inquiry and faith-based systems. Recognizing these tactics is essential for meaningful dialogue.

Conclusion: Rationality as a Lifeline

To live without faith in an ideology is not to live without a guide. The guide is reason, tethered to the evidence that reality provides. This approach, while perhaps less comforting than faith-based systems, is far more reliable. It allows us to grow, to adapt, and to inch ever closer to truths that are as provisional as they are profound.

To ask what we should place our faith in after rejecting the Christian God is to misframe the question. We should not seek to place faith in anything. Rather, we should strive to proportion belief to the evidence and embrace uncertainty as a friend, not an enemy. This is the path of intellectual courage, the path of Nick, and the path that truly honors the complexity of existence.

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Evidentialism Is Not an Ideology

- Premise 1: An ideology is a rigid system of beliefs shaping one’s worldview.

- Premise 2: Evidentialism is a methodological stance that aligns beliefs with evidence and revises them as evidence evolves.

- Conclusion: Evidentialism is not an ideology but a framework for avoiding ideological rigidity.

Argument 2: Faith-Based Belief Systems Are Psychologically Comforting but Epistemically Flawed

- Premise 1: Faith-based belief systems prioritize emotional comfort by providing answers to unexplained phenomena.

- Premise 2: Faith often leads to superstitions and unfounded beliefs that hinder the pursuit of knowledge.

- Conclusion: While faith-based belief systems may offer comfort, they are epistemically inferior to evidence-based reasoning.

Argument 3: “I Don’t Know” Is an Honest and Coherent Response

- Premise 1: Acknowledging uncertainty signals the ability to recognize the boundary between knowledge and ignorance.

- Premise 2: Premature assertions of belief foster confirmation bias and impede genuine understanding.

- Conclusion: Admitting “I don’t know” is a coherent and intellectually honest response when evidence is insufficient.

Argument 4: Not All Trust Is Faith

- Premise 1: Faith involves belief that exceeds or contradicts available evidence.

- Premise 2: Trust based on evidence is revisable and evolves with new information.

- Conclusion: Trust based on evidence is distinct from faith and cannot be equated with it.

Argument 5: Adopting Ideologies Beyond Evidence Is Irrational

- Premise 1: Rational beliefs are proportional to the evidence supporting them.

- Premise 2: Ideologies adopted without sufficient evidence foster cognitive dissonance and epistemic instability.

- Conclusion: Adopting ideologies that exceed available evidence is irrational.

Argument 6: A Person Without an Ideology Should Be Commended

- Premise 1: A person who aligns beliefs with evidence embodies intellectual humility.

- Premise 2: This approach fosters flexibility, openness to correction, and adaptability to changing circumstances.

- Conclusion: A person without an ideology, committed to evidence-based belief, should be commended rather than pitied.

Argument 7: Faith-Based Epistemology Is Fundamentally Flawed

- Premise 1: Faith-based epistemology encourages confirmation bias, discourages questioning, and inhibits discovery.

Premise 2: Rational inquiry prioritizes evidence, questioning, and the pursuit of accurate understanding.

Conclusion: Faith-based epistemology is inferior to evidence-based rational inquiry.

Argument 8: Fallacies Obscure Rational Debate

- Premise 1: Fallacies like tu quoque, false equivalence, and strawman arguments misrepresent rational approaches as ideologies or faith.

- Premise 2: These fallacies hinder meaningful dialogue and obscure the distinction between faith and evidence-based reasoning.

- Conclusion: Recognizing and avoiding fallacies is essential for constructive ideological debates.

Argument 9: Rationality Offers a Superior Guide

- Premise 1: Reason, tethered to evidence, provides a reliable framework for navigating complexity and uncertainty.

- Premise 2: Faith, which exceeds evidence, lacks the adaptability and reliability of rational inquiry.

- Conclusion: Rationality, not faith, is the superior guide for understanding and engaging with the world.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Faith vs. Rationality

CHRIS: Why don’t you place your faith in God? Everyone believes in something—whether it’s religion, science, or themselves.

CLARUS: That’s a common misconception. Faith involves holding a belief that exceeds or contradicts the evidence, while I align my beliefs with the available evidence. This isn’t the same as faith—it’s a commitment to evidentialism, which is not an ideology.

CHRIS: But isn’t this commitment to evidence itself an ideology? You’ve just replaced faith in God with faith in reason or science.

CLARUS: Not at all. An ideology is a rigid system of beliefs. My approach, evidentialism, is a methodology, not an ideology. It allows me to revise my beliefs as new evidence arises, unlike ideological frameworks that resist change.

CHRIS: Don’t you think it’s better to have faith in something rather than saying, “I don’t know”? That seems weak and directionless.

CLARUS: Quite the opposite—admitting “I don’t know” demonstrates intellectual integrity and opens the door to genuine discovery. Prematurely adopting beliefs without sufficient evidence leads to confirmation bias and hinders understanding.

CHRIS: So, you’re saying it’s okay to have no answers at all? That sounds unsettling.

CLARUS: It’s more unsettling to cling to unfounded beliefs that close off inquiry. Admitting uncertainty fosters curiosity and ensures that when we do reach conclusions, they are grounded in reality.

CHRIS: But you can’t live without trust in something. Surely you have faith in science or reason.

CLARUS: I trust science and reason because they are based on evidence, but this trust is revisable. Faith is inflexible—it persists regardless of contradictory evidence. My trust is not faith; it’s confidence proportional to the evidence.

CHRIS: Why not just adopt faith in God if it brings comfort? Doesn’t it serve a purpose?

CLARUS: Faith might bring psychological comfort, but it sacrifices epistemic rigor. It encourages confirmation bias, discourages questioning, and inhibits the pursuit of accurate knowledge. Rational inquiry, on the other hand, fosters adaptability and openness to new truths.

CHRIS: You seem to think faith is fundamentally flawed. Isn’t that harsh?

CLARUS: It’s not harsh; it’s realistic. Faith discourages critical thinking by valuing belief over evidence. Rational inquiry challenges us to seek truth, even if it’s uncomfortable. It’s the path to growth and understanding.

CHRIS: But some argue that everyone worships something—whether it’s money, success, or even evidence itself.

CLARUS: That’s another misunderstanding. I don’t worship evidence; I follow where it leads. Worship implies an emotional or spiritual attachment, but my commitment to evidence is rational, revisable, and practical.

CHRIS: Aren’t you being a bit rigid yourself? You seem so sure that rationality is better than faith.

CLARUS: I’m confident, not rigid, because my position is based on evidence and remains open to revision. Rationality isn’t a static ideology—it’s a dynamic process that evolves with new information.

CHRIS: So, you believe your approach is superior to faith?

CLARUS: Yes, because it aligns with reality and fosters intellectual humility. Rationality provides a reliable framework for navigating complexity and uncertainty, while faith demands unwavering belief regardless of the evidence. That difference makes all the difference.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Compass vs. the Fixed Map

Imagine navigating an unfamiliar wilderness. A compass, like rationality, provides consistent direction based on reality and adjusts to changes in terrain. In contrast, a fixed map, like faith, assumes a predetermined layout regardless of the actual environment. While the fixed map might provide comfort through certainty, it becomes useless—or even dangerous—when the terrain doesn’t match its depiction. Rationality, like the compass, is a flexible tool that evolves with evidence, ensuring reliable navigation through life’s uncertainties.

Analogy 2: The Provisional Diagnosis

Consider a doctor evaluating a patient with unclear symptoms. The doctor who relies on evidence, like a rational thinker, waits for test results to form a provisional diagnosis. In contrast, a doctor who relies on guesswork, akin to faith, declares a diagnosis prematurely, risking misdiagnosis and harm. By embracing uncertainty and allowing beliefs to develop with evidence, the first doctor demonstrates intellectual humility and ensures better outcomes, while the second sacrifices accuracy for false certainty.

Analogy 3: Building a House on Bedrock vs. Sand

Imagine constructing a house. Building on bedrock, like forming beliefs based on evidence, provides a stable foundation that withstands scrutiny and environmental changes. Building on sand, like adhering to faith, might seem easier and faster, but it lacks the resilience to endure shifting circumstances. Over time, the sand shifts, and the structure collapses, while the house on bedrock stands firm. Rational inquiry, like building on bedrock, prioritizes long-term stability and reliability over immediate gratification.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Evidentialism Itself Relies on Faith

Theologians might argue that evidentialism assumes the reliability of human reason and empirical observation without providing proof for these assumptions. This reliance on unprovable premises is itself a form of faith, making evidentialism no less ideological than religion.

2. Faith and Evidence Are Not Mutually Exclusive

Some theologians could contend that faith does not necessarily reject evidence. For instance, they might claim that belief in God is supported by historical evidence, philosophical arguments, and personal experience, and that faith is simply trust in this body of evidence.

3. “I Don’t Know” Is a Philosophically Vacuous Position

Theologians might argue that stating “I don’t know” without engaging with deeper metaphysical questions avoids addressing life’s most critical issues. They could suggest that faith fills the gap, providing meaning and purpose where evidence falls silent.

4. Trust in Science Requires Faith

Theologians might assert that trust in science is akin to faith because it assumes the uniformity of nature, the validity of logic, and the accuracy of human perception—concepts that cannot be empirically proven and must be taken on faith.

5. Faith Complements Rationality

It might be argued that faith is not a replacement for evidence but a necessary companion to rationality. Theologians could claim that faith fills epistemic gaps that reason alone cannot bridge, enabling humans to address questions of morality, purpose, and ultimate reality.

6. Faith Produces Tangible Benefits

Theologians might highlight the psychological, social, and ethical benefits of faith, such as providing hope, fostering community, and promoting altruistic behavior. These tangible outcomes could be presented as evidence that faith is not inferior to rational inquiry.

7. Rationality Alone Is Insufficient

Some theologians could claim that rationality, while useful, cannot address the ultimate questions of existence, such as why there is something rather than nothing. Faith, they might argue, transcends rationality to provide answers that science and logic cannot reach.

8. Misrepresenting Faith as Dogmatism

Theologians may argue that the content conflates faith with blind dogmatism, ignoring the nuance in many religious traditions where faith includes doubt, questioning, and openness to reinterpretation. This misrepresentation could be seen as a strawman argument.

9. Rational Inquiry Presupposes Metaphysical Truths

Theologians might argue that rationality depends on objective metaphysical principles, such as the existence of truth and the reliability of logic, which cannot be justified through empirical means alone. Faith in these principles underpins all rational inquiry.

10. Faith Is Not About Certainty

Some theologians might emphasize that faith does not claim absolute certainty but involves trust despite incomplete knowledge. This trust, they could argue, is not irrational but a reasonable response to the limits of human understanding.

Counter-Responses

1. Evidentialism Itself Relies on Faith

Evidentialism does not rely on faith but on pragmatic justification. The reliability of human reason and empirical observation is supported by their consistent success in explaining and predicting phenomena. This is not a leap of faith but an inductive inference based on observed patterns, which remains open to revision should evidence arise against their reliability.

2. Faith and Evidence Are Not Mutually Exclusive

While faith and evidence can coexist, faith is defined by believing beyond or against the evidence. For instance, historical claims supporting religious doctrines often fail to meet the rigorous standards of peer-reviewed historical analysis, and personal experiences, while compelling, are inherently subjective and prone to bias. Rational inquiry prioritizes publicly verifiable evidence, which faith often lacks.

3. “I Don’t Know” Is a Philosophically Vacuous Position

Acknowledging “I don’t know” is not vacuous but intellectually honest and foundational to further inquiry. Accepting ignorance in the absence of evidence prevents the adoption of premature or erroneous conclusions. Unlike faith, this position maintains an openness to future evidence, fostering genuine understanding rather than filling gaps with unfounded assumptions.

4. Trust in Science Requires Faith

Trust in science is not equivalent to faith because it is empirically grounded and self-correcting. Science assumes uniformity not arbitrarily but because this assumption has repeatedly proven reliable in practice. These assumptions remain provisional, meaning they can be revised if contradictory evidence arises, which distinguishes science from faith.

5. Faith Complements Rationality

Faith does not complement rationality if it involves beliefs that exceed the bounds of evidence. While rationality addresses gaps in knowledge through inquiry, faith closes those gaps prematurely, often impeding further investigation. Rationality alone is sufficient for grappling with moral, existential, and epistemological questions through a process of reasoned exploration.

6. Faith Produces Tangible Benefits

The tangible benefits attributed to faith, such as psychological comfort or social cohesion, do not justify its epistemic validity. Similar benefits can arise from secular systems, such as community-driven humanism or evidence-based therapeutic practices. Faith’s utility does not equate to its truthfulness, which must be assessed independently of its consequences.

7. Rationality Alone Is Insufficient

While rationality may not yet answer ultimate questions, this does not justify defaulting to faith. The absence of current answers does not validate unsupported beliefs but rather highlights the need for continued inquiry. Faith provides illusory answers that can mislead, whereas rationality preserves the integrity of the search for truth.

8. Misrepresenting Faith as Dogmatism

Faith may not always be rigid dogmatism, but it still involves believing beyond evidence. Even when faith includes doubt or questioning, it often requires commitment to specific doctrines without sufficient justification. This distinguishes it from evidentialism, which evolves entirely in proportion to the strength of the evidence.

9. Rational Inquiry Presupposes Metaphysical Truths

Rational inquiry does not presuppose metaphysical absolutes but builds on pragmatic, empirically justified principles. For example, the consistency of logic and the reliability of observation are based on their demonstrated utility rather than blind faith. These principles remain open to revision, which faith-based systems often resist.

10. Faith Is Not About Certainty

Even if faith is not about absolute certainty, it still demands belief beyond evidence, which distinguishes it from rational inquiry. Trusting in incomplete knowledge is not inherently irrational, but faith often involves committing to conclusions that cannot be adequately supported, which undermines its epistemic credibility.

Clarifications

Faith vs. Rationality

Introduction:

Imagine standing on a shaky bridge over a roaring river. Beneath you is faith: the comforting notion that, no matter how weak the planks are, you’ll cross safely if you just believe. Rationality, however, offers something sturdier—an engineered structure built on evidence and tested through trial and error. Which would you trust with your life? The answer reveals a deeper truth about the way we navigate uncertainty.

Faith has long been celebrated as a virtue, lauded for its role in providing hope, meaning, and purpose. But beneath the veneer of its emotional appeal lies an uncomfortable reality: faith, by definition, bypasses the safeguards of evidence and critical scrutiny. This makes it not only unreliable but also inherently irrational. Rationality, in contrast, thrives on evidence, logic, and adaptability. It may lack faith’s comforting shortcuts, but it offers something far greater: the intellectual tools to engage with reality as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Section 1: What Is Faith?

Faith is often presented as a benign or even noble act of trust, but its defining feature is believing beyond—or in spite of—the evidence. For instance, religious faith may insist on the literal truth of sacred texts, even when they contradict historical or scientific evidence. Similarly, pseudosciences like astrology rely on emotional resonance rather than empirical support. What unites these examples is their immunity to falsification: Faith does not seek evidence; it resists it.

Why does faith hold such appeal? It bypasses intellectual rigor, offering certainty where none exists. This cognitive shortcut feels satisfying but comes at a cost: It leaves beliefs untested and unaccountable. Unlike rational inquiry, which demands the labor of questioning and evaluating, faith asks only for submission.

— A Comprehensive Survey of Biblical Faith

Section 2: What Is Rationality?

Rationality, by contrast, operates on the principle that belief should be proportional to evidence. If the evidence is strong, the belief is strong; if the evidence is weak, the belief is tentative. This method, though less comforting than faith, is far more reliable. Rationality thrives on tools like critical thinking and empirical observation, which collectively guard against biases and errors.

Consider the progress of science: From the eradication of diseases to the mapping of the cosmos, rationality has transformed human understanding. Its strength lies in its adaptability—unlike faith, which resists change, rationality evolves with new information. Intellectual humility is not a weakness but a hallmark of rationality: the willingness to revise beliefs in the face of better evidence.

Section 3: Common Defenses of Faith

Faith’s defenders often claim that everyone exercises it, but this is a semantic sleight of hand. When a scientist trusts their instruments or a friend trusts their partner, this is not faith but confidence grounded in evidence. Faith, by contrast, demands belief without—or beyond—such grounding.

The emotional appeal of faith is another common defense. Yes, faith may provide comfort, but comfort is not the same as truth. A placebo might make you feel better temporarily, but only evidence-based medicine can cure the underlying ailment. Similarly, the ethical benefits attributed to faith—such as altruism—can be cultivated through secular, evidence-based systems of morality without the epistemic pitfalls of faith.

Section 4: Faith’s Harmful Consequences

Faith, far from being harmless, often fosters dogmatism and discourages questioning. Consider the anti-science movements that reject vaccines or climate change based on faith-driven ideologies. These movements thrive on confirmation bias, selectively accepting evidence that aligns with their beliefs and dismissing the rest.

The harm extends beyond intellectual stagnation. Faith has historically fueled sectarian violence, from religious wars to modern-day extremism. By demanding uncritical allegiance, it erects barriers to dialogue and cooperation. In a world facing global challenges, the divisiveness of faith is not a virtue but a liability.

Section 5: Rationality as the Superior Framework

Rationality, in contrast, offers a shared language of evidence and logic. It welcomes doubt, not as a threat, but as an invitation to learn. Unlike faith, which clings to certainties, rationality thrives in uncertainty, transforming it into a catalyst for discovery.

Consider the achievements of rational inquiry: It has unlocked the secrets of DNA, explored distant galaxies, and harnessed energy from the atom. These advances were not the result of faith but of critical scrutiny and evidence-based reasoning. Rationality is not just a tool for understanding the world; it’s a framework for fostering cooperation and progress.

Conclusion

Faith might offer the illusion of stability, but it is a rickety bridge—an act of trust unsupported by evidence. Rationality, though less comforting, provides the tools to build bridges that last. By aligning belief with evidence and welcoming doubt, we gain not only a clearer understanding of reality but also the ability to navigate its complexities with integrity.

The time has come to embrace rationality not merely as an alternative to faith but as its superior. This is not an abandonment of wonder or meaning but a reorientation—away from dogmatic certainty and toward the exhilarating pursuit of truth. Let us leave faith behind and build a culture that celebrates evidence, questions assumptions, and values the courage to say, “I don’t know.” That courage, after all, is the foundation of all progress.

Leave a comment