◉ This post consists of three essays that address the nature and source of logic, and particularly whether logic has a necessary connection to a God.

Essay #1:

The Inevitability of Logic: Structure, Subjectivity, and Predictive Power

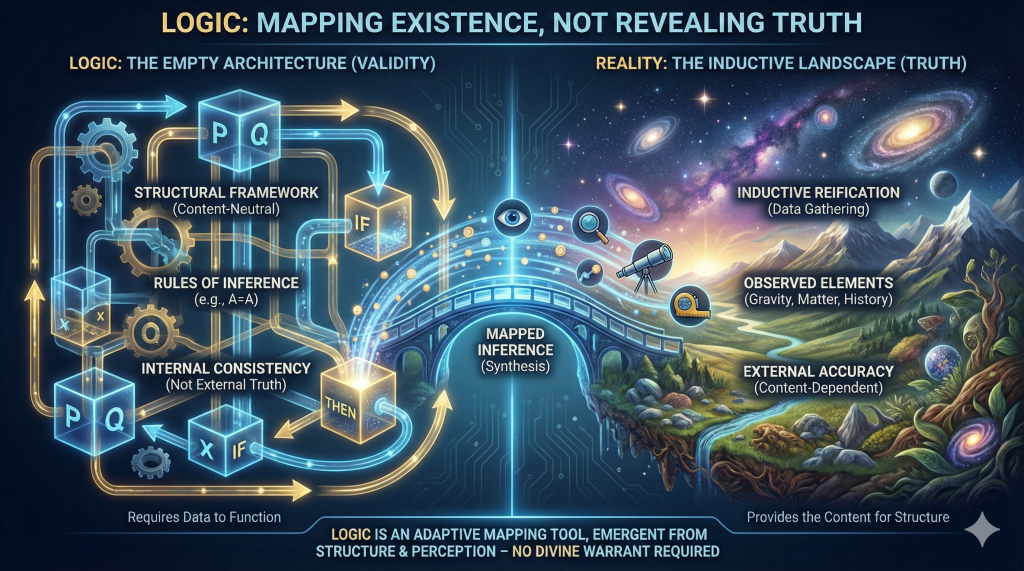

Existence, by its very nature, implies structure. Whether it’s a rock, a galaxy, or an incomprehensible extra-dimensional entity, anything that is possesses properties—shape, behavior, patterns—that distinguish it from nothingness. This inherent structure, no matter how simple or alien, provides a foundation upon which subjective minds, like ours, can impose logic. This essay argues that as long as something exists and we can perceive its structure, we are compelled to assign it a logic, driven by our capacity for inductive inference and the pursuit of predictive success. Even when that structure shifts beyond recognition, the process endures, adapting to new realities as if they were fresh universes ripe for exploration.

The starting point is straightforward: existence and structure are inseparable. A tree has branches and roots; a quantum fluctuation has probabilities and states. Even chaos, in its unpredictability, carries a kind of structure—a rhythm of disorder. This observation aligns with how human perception operates. As Immanuel Kant suggested, our minds filter reality through innate categories like space, time, and causality, rendering raw existence into something structured and intelligible. Wherever there is something, we find form, and where there is form, we instinctively seek meaning.

From this structure emerges logic—not as an inherent truth baked into the universe, but as a human construct born of subjectivity. When we encounter a tree, we don’t merely see it; we interpret it through a logic of biology or physics, attributing its form to growth or evolution. This logic need not be complete or absolute. Consider an incomprehensible entity—a writhing, Lovecraftian blob pulsing in ways that defy our grasp. Its full nature might elude us, yet if we perceive it pulsing every 13 seconds, we’ve identified a structure. From that, we can build a predictive logic: “At 13 seconds, it acts.” This is the crux of the argument: structure, once perceived, invites a logic tailored to its patterns, however partial or pragmatic.

The power of this logic lies in its inductive roots and predictive utility. Induction doesn’t demand total understanding; it thrives on regularity. If the blob eats only left socks, we can predict safety by tossing one its way—knowledge of its deeper “why” is irrelevant. This echoes how science operates. Long before Newton formalized gravity, people inferred that rocks fall, shaping practical rules without a full theory. Today, we predict black hole behavior through equations we don’t wholly comprehend. As long as structure yields consistent outcomes, we can formulate a logic that works, refining it as new data emerges.

But what happens when structure changes—when the blob stops pulsing at 13 seconds or devours a right sock? Does the breakdown of our inductive inferences unravel the argument? Far from it. A radical shift in structure doesn’t erase the process; it redefines the playing field. The altered blob becomes a new system—a fresh “universe” with its own regularities to probe. If it now favors argyle socks on Tuesdays, we adapt, crafting a revised logic from fresh observations. This mirrors how physics evolved from Newtonian mechanics to relativity: the universe’s structure deepened, and our inductive tools followed suit. Existence remains structured; only the patterns shift, and our minds, ever tenacious, recalibrate.

This adaptability underscores the resilience of the position. As long as something exists, it bears properties—however strange or mutable—and those properties offer a foothold for perception. From perception, we extract regularities; from regularities, we forge logic. The cycle persists, unbroken by complexity or change. Whether facing a tree, a quantum state, or a sock-hungry blob, the subjective mind will find structure and assign it meaning, driven not by cosmic decree but by its own nature. And as long as that logic delivers predictive power, it holds value, provisional though it may be.

In conclusion, the interplay of existence, structure, and subjective logic is inescapable. Where there is something rather than nothing, there is form; where there is form, we perceive and interpret; and where we interpret, we predict. This process, rooted in induction, thrives on the mere fact of structure, adapting even when the ground beneath it shifts. Existence invites logic not because it demands it, but because we, as perceiving beings, cannot help but seek it—an enduring testament to the mind’s relentless dance with the real.

Caution: The logic emerging from structure in this discussion shouldn’t be hastily equated with traditional Aristotelian logic, which is grounded in fixed categories—such as ‘all men are mortal‘—and syllogistic reasoning that builds rigid conclusions from universal premises. In contrast, the form of logic referred to in this essay is often fluid, inductive, and pragmatic, shaped by subjective perception and finely tuned to the specific, shifting patterns of a given structure, rather than adhering to timeless axioms. For example, consider observing a flock of birds: we might inductively note they scatter when a predator nears, forming a practical logic—’if a hawk appears, the flock disperses‘—without needing a universal rule. Yet, there’s a suspicion that any logic we discern within structure may still echo Aristotelian logic in its basic form, not because logic creates structure or structure dictates logic, but because their essences seem deeply entwined. The birds’ predictable scattering could be framed Aristotelian-style as ‘all flocks disperse when threatened,’ suggesting an intrinsic harmony between the objective reality of structure and the subjective act of interpreting it, bridging the raw world and our reasoning about it.

Essay #2:

The Necessity of God in Explaining Logic: A Rigorous Analysis

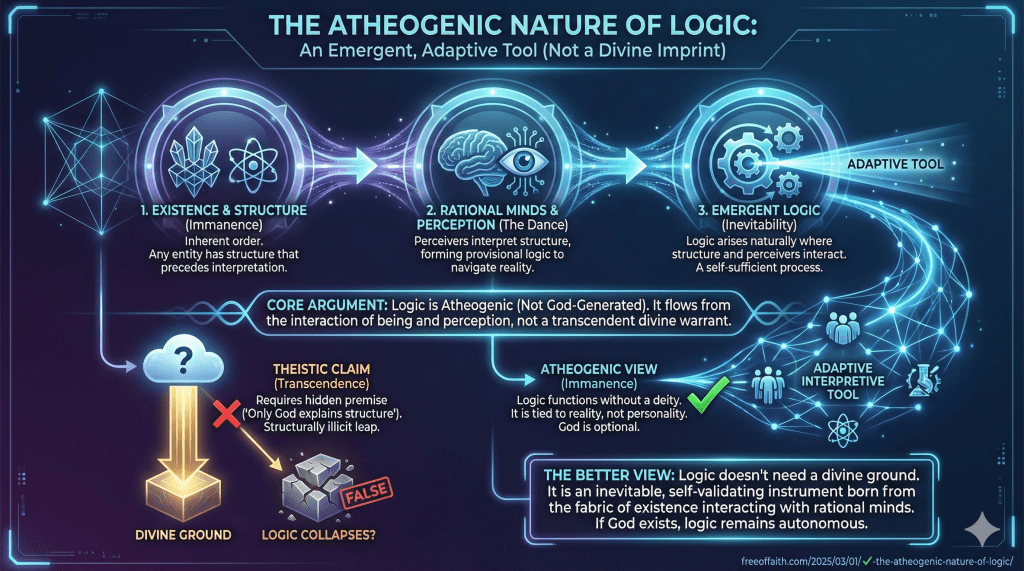

The question of whether we need a God to explain logic hinges on dissecting the relationship between existence, structure, perception, and the emergence of logic itself, as presented in the essay “The Inevitability of Logic: Structure, Subjectivity, and Predictive Power.” The original essay posits that logic arises inevitably from the interplay of existence—which inherently possesses structure—and human perception, which interprets that structure through inductive inference to achieve predictive success. This analysis will rigorously evaluate whether this process requires a divine entity, arguing that logic, as described, stands independently of God, though it does not preclude the possibility of divine involvement.

To begin, the essay asserts that existence and structure are inseparable. Anything that exists—a rock, a galaxy, or an alien blob—has properties like shape, behavior, or patterns that distinguish it from nothingness. This structure is not contingent on its origin but is a given: if something is, it has form. From this, human perception, shaped by subjective faculties, engages with structure to produce logic. This logic is not an absolute truth embedded in the cosmos but a pragmatic construct, forged through induction—the process of deriving general rules from specific observations. For instance, if a blob pulses every 13 seconds, we infer a pattern and predict its next pulse, regardless of deeper metaphysical “whys.” The question is whether this cycle—existence to structure to perception to logic—requires God as a necessary condition.

Let’s test this logically. The chain begins with existence: “something rather than nothing.” The essay takes this as a premise, focusing on its implications rather than its cause. A theistic argument might insert God here as the reason for existence, positing a first cause or creator who imbues reality with structure. Yet, the essay’s framework does not depend on resolving why existence occurs—only that it does. Given existence, structure follows naturally: a rock has mass, a blob has rhythms. Whether God crafted this structure is irrelevant to the next step; the structure exists for us to perceive, divine origin or not.

Next, perception: humans, as subjective beings, interpret structure through innate filters—space, time, causality—and generate logic. Could God be necessary for these perceptual capacities? A naturalistic explanation, such as evolutionary adaptation, suggests that minds capable of spotting patterns and predicting outcomes (e.g., avoiding predators) would survive and develop. The essay implicitly aligns with this: our “relentless dance with the real” drives logic as a survival tool, not a divine endowment. A theist might argue that God designed these minds, but this is an additional assumption, not a logical necessity. The process functions as long as perception exists, regardless of its source.

The emergence of logic from this interplay is key. Inductive inference—observing that rocks fall or blobs pulse—yields predictive rules without requiring complete understanding. This logic is fluid and adaptable: if the blob shifts to a 14-second pulse, we revise our predictions based on new structure. The essay likens this to scientific progress, from Newtonian mechanics to relativity, where logic evolves with observed patterns. No divine overseer is needed to sustain this adaptability; it’s a self-contained response to existence and perception. Thus, the core mechanism—structure plus perception equals logic—operates independently of God.

Consider an objection: without God, why should reality’s structure be consistent or our perception reliable enough for logic to work? If the universe were chaotic or our minds deceptive, predictive success might falter. The essay counters this by emphasizing pragmatism over absolutes. Logic succeeds when it predicts—rocks fall, blobs eat socks—and that’s sufficient. It doesn’t claim reality must be structured, only that it is, and we leverage what we find. A theist might insist God ensures this reliability, but this is a metaphysical overlay, not a logical requirement. The observed harmony between structure and logic could be a happy accident or an evolved trait, not proof of divine intent.

The essay’s distinction between its inductive, pragmatic logic and traditional Aristotelian logic—with its fixed categories like “all men are mortal”—further clarifies this. While Aristotelian logic seeks universal truths, the essay’s logic is provisional, tied to specific patterns (e.g., “this flock scatters when a hawk nears”). Yet, it notes a potential overlap: the flock’s behavior could fit an Aristotelian syllogism, hinting at a resonance between structure and reasoning. Does this suggest God? Not necessarily—it’s a descriptive alignment, not a causal mandate. The “intrinsic harmony” might reflect co-evolution of mind and world, not divine orchestration.

In conclusion, we do not need a God to explain logic within this framework. Existence provides structure, perception interprets it, and logic emerges through induction, delivering predictive success without requiring a divine foundation. God could be the source of existence or perception, but the process from structure to logic stands alone, like dough forming from flour and water regardless of a baker’s intent. This logic is a human artifact, resilient and adaptable, born of our engagement with reality. If God exists, it’s an optional backdrop, not a logical necessity. The dance of mind and structure persists, divine partner or not.

Symbolic Logic Formalization

Definitions and Symbols

: “x exists” – A predicate indicating that x is an entity in reality.

: “x has structure” – A predicate indicating that x possesses properties or patterns.

: “x is perceived by a subjective mind” – A predicate indicating human perception of x.

: “x gives rise to logic” – A predicate indicating that a logic is constructed for x.

: “God exists” – A propositional variable representing the existence of God.

: Material implication (if-then).

: Conjunction (and).

: Universal quantifier (for all).

: Negation (not).

: Necessity operator (it is necessary that).

The argument will show that logic () follows from existence (

), structure (

), and perception (

), and that God (

) is not logically required.

Formalization of the Argument

Premise 1: Existence Implies Structure

The essay asserts that anything that exists has structure. Symbolically:

Translation: For all x, if x exists, then x has structure. This captures the idea that existence inherently comes with properties (e.g., a rock’s mass, a blob’s pulse).

Premise 2: Structure and Perception Imply Logic

When a mind perceives structure, it constructs logic (via induction). Symbolically:

Translation: For all x, if x has structure and x is perceived, then x gives rise to logic. This reflects the essay’s claim that perception of structure (e.g., a 13-second pulse) leads to predictive logic.

Premise 3: Existence and Perception Are Observed

The essay assumes existence and perception as starting points. For some entity x (e.g., a tree or blob):

Translation: There exists an x that exists and is perceived. This is a specific instance, not a universal claim, aligning with the essay’s focus on what we encounter.

Logical Inference:

From Premises 1, 2, and 3, we derive logic:

(from Premise 1, instantiation).

(Premise 3).

(from 2, simplification).

(from 1 and 3, modus ponens).

(from 2, simplification).

(from 4 and 5, conjunction).

(from Premise 2, instantiation).

(from 6 and 7, modus ponens).

Thus:

Translation: Logic arises for x. This confirms that logic emerges from existence and perception.

Premise 4: God as a Possible Condition?

A theistic counterclaim might assert that God is necessary for existence or perception. Symbolically:

(God implies all things exist)

or

(God implies perception exists).

But necessity would be:

(It’s necessary that God causes existence).

The essay doesn’t assume this. Instead, it treats E(x) and P(x) as givens, not requiring G.

Conclusion: God Is Not Necessary

Does logic require God? Test the necessity:

(Is it necessary that God implies logic?)

From the derivation above, follows from

alone. We can deny G without affecting the chain:

Translation: If God doesn’t exist, and x exists and is perceived, logic still arises. This holds because neither nor

logically depends on

in the essay’s framework.

Thus, the final claim:

Translation: It is not necessary that God exists for logic to arise. Logic stands without God, though G isn’t disproven—it’s just not required.

Summary in Symbolic Form

This formalizes the argument: logic (L) follows from existence (E) and perception (P) via structure (S), and God (G) is not a necessary condition. The system is self-contained, mirroring the essay’s conclusion that logic is a human response to reality, not a divine mandate.

Essay #3:

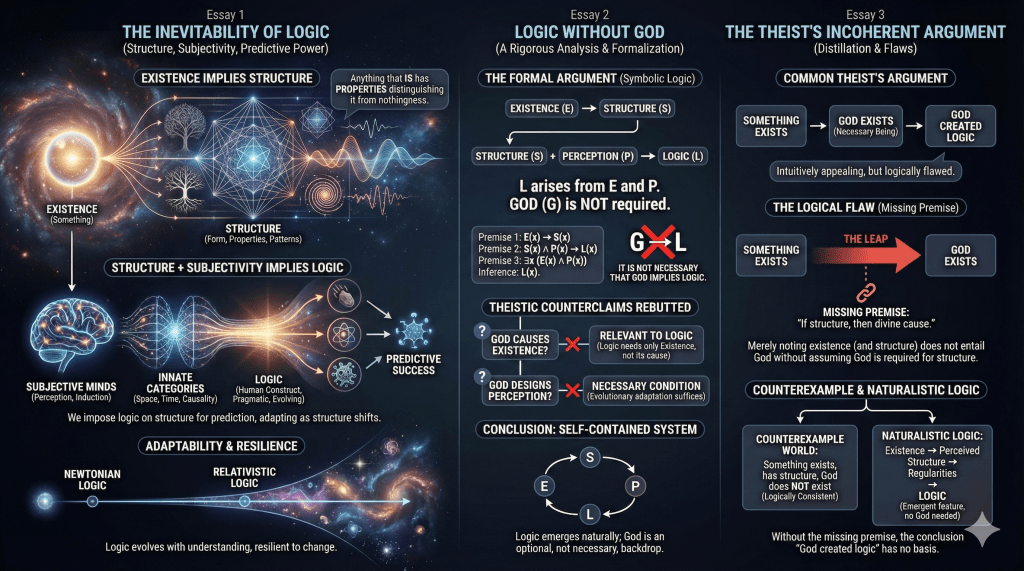

1. Distillation of the Common Theist’s Argument

- The Basic Claim

Many theists maintain that because there is something rather than nothing, it follows that God must exist. From there, they conclude that because logic arises from the structure of what exists, God must have created that logic. Put more succinctly:- “There is something rather than nothing.”

- “Therefore, God exists.”

- “Therefore, God created logic.”

- Symbolic Form

In symbolic logic, this can be expressed as follows: - Why This Looks Intuitive

The chain feels compelling because it appears to solve an ultimate question: Where did logic (or anything at all) come from? By tying existence to a necessary being (God) and then tying logic to that necessary being, it creates the illusion of a closed circle of explanation:- We see structure in reality, so we assume there must be a structurer.

- That structurer is then posited to be the source of all logic, including our own.

2. Why the Argument Is Logically Incoherent

- Missing the Critical Premise

The jump from “something exists” to “God exists” presupposes an additional premise like “if there is structure, then that structure must come from a divine being.” Without this premise, there is no logical bridge to God. Merely noting that something exists (and therefore has structure) does not entail a divine source. This is often presented as:(something exists),

(anything that exists has some structure),

- (But we never prove

).

- Counterexample World

We can conceive of a world (a “model”) in which something exists, that something has structure, yet God does not exist. If such a scenario is logically consistent, then it proves “there is something rather than nothing” does not necessitate “God exists.” The theist needs an additional premise—one that is far from self-evident. - Logic Arising Without a Deity

Even assuming God exists, we cannot simply assert that God is the creator of logic. A naturalistic explanation might say logic is an emergent feature of structure: as soon as anything with consistent, identifiable patterns exists, logic is the description of those patterns. That is:- Existence → Perceived structure → Formulation of regularities → Logic.

- At no point here must we posit God.

- Why the Conclusion Fails

Because the link “If something has structure, then it comes from God” is unproven, the final conclusion “God created logic” has no basis. One must accept as a prior that a divine being is required for any structure whatsoever. Nothing in standard reasoning forces us to adopt that premise. - Summary

- Claim: “Something exists, so God exists, and God created logic.”

- Reality: We need a specific premise that equates the mere fact of structure with divine causation. Without it, the conclusion simply does not follow.

- Incoherence: Symbolically, the absence of

means we cannot derive

from

. Likewise, we cannot derive “God created logic” from God’s existence unless we add yet another unsubstantiated premise.

Symbolic Logic Formalization

Demonstrating That “Something Exists” Does Not Necessarily Imply “God Exists”

Below is an expanded symbolic formulation showing how, absent a special premise linking structure to God, it does not follow from “something exists” that “God exists.”

Symbols

: “x exists.”

: “x has structure.”

: “God exists.”

: “there exists some x.”

: “for all x.”

: “implies” (material implication).

Premises

- Something exists.

There is at least one entity

that exists.

- Existence implies structure.

If any entity

exists, it must have some structure.

Notice: We do not include a premise like “.” Without this additional assumption, there is no logical path from

to

.

Why We Cannot Derive God

- From premise (1), we have:

.

- From premise (2) plus the entity in (1), we get:

,

because if something exists (), it has structure (

).

- But without an additional premise stating that “if structure exists, then God exists,” we have no rule that takes us from

to

. Hence, we cannot conclude

from these premises alone.

Model Demonstration (Counterexample)

In predicate logic, a simple way to prove that “from these premises we cannot conclude ” is to show a model (a scenario) in which:

- All premises are true, but

(God exists) is false.

If such a model is consistent, then does not logically entail

.

Construct a Model

- Domain:

(exactly one object, called “a”).

- Interpretation:

: “a” exists.

: “a” has structure.

: God does not exist in this model.

Check the premises:

- Premise (1):

is true because “a” does indeed exist in our model.

- Premise (2):

is satisfied because “a” both exists and has structure, so

is true.

Conclusion: Since in this model, yet both premises remain true, there is no logical necessity that

must be true.

Hence, from “something exists” and “existence implies structure” alone, we cannot conclude “God exists.” An extra premise—e.g., “”—is required to derive

.

Summary

- Merely knowing “

” (something exists) and “

” (whatever exists has structure) does not logically yield “

.”

- One must add a dedicated premise linking structure to divinity—like “

”—to infer that God exists.

- Without such a premise, there is no valid derivation from “something exists” to “God exists.”

Leave a comment