Definitions of Statements:

Let:

= “The Apostles would not die for a lie”

= “The Apostles’ belief in Jesus was true”

= “Non-believers know God exists (Romans 1:20)”

= “Non-believers die rejecting God”

= “Dying for a belief proves that belief is true”

Logical Formulation of the Christian Apologist’s Argument:

- Apostles’ Martyrdom Argument:

(If the Apostles wouldn’t die for a lie, then their belief must be true.)

(Dying for a belief is proof that belief is true.)

- Romans 1:20 Claim:

(Non-believers know God exists.)

(Non-believers die rejecting God.)

(Non-believers die rejecting something they “know” is true.)

- Contradiction in Reasoning:

- From

, if dying for a belief proves it true, then non-believers dying while rejecting God would imply atheism is true.

- However, Christianity insists that non-believers know God exists, which means they are dying rejecting a truth.

- This contradicts the assertion that people do not die for what they know is false (used in the Apostles’ argument).

- From

Formal Contradiction:

(Apostles’ martyrdom proves Christianity is true.)

(Non-believers die rejecting God, and dying for a belief proves its truth.)

- Contradiction:

(Christianity is true, but also atheism is true.)

Since a contradiction () is logically impossible, the original reasoning must be flawed.

Resolution:

To avoid the contradiction, one of the following must be rejected:

- Dying for a belief does not necessarily prove it is true (Reject

).

- Non-believers do not actually “know” God exists (Reject

).

Without this, the reasoning is self-refuting and logically incoherent.

The Incoherence of the “Would Not Die for a Lie” Argument in Light of Romans 1:20

Introduction

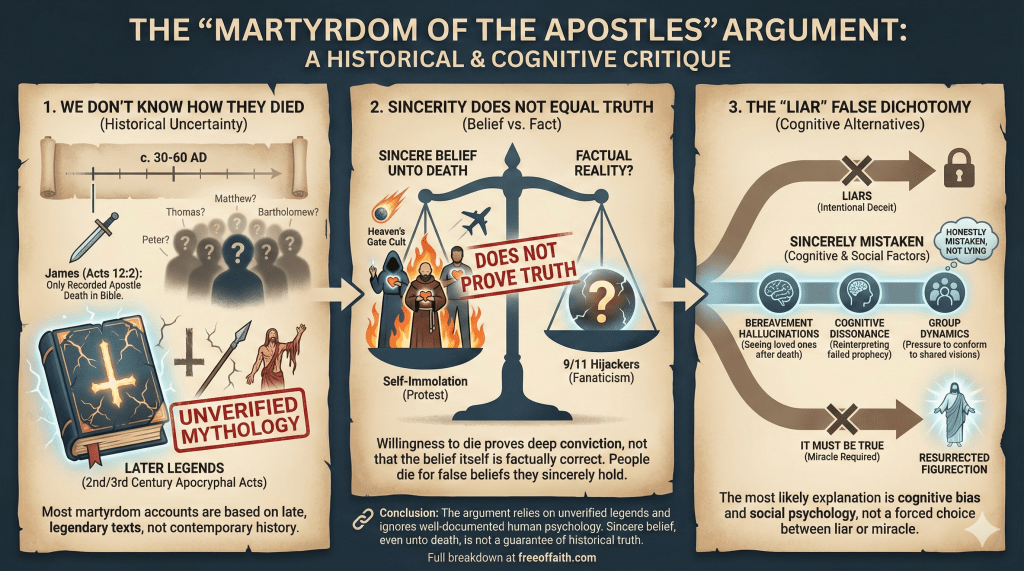

The argument that the apostles “would not have died for a lie” has long been used as a rhetorical and apologetic tool to support the truth of Christianity. This claim asserts that since the apostles willingly suffered martyrdom, their belief in Jesus’ resurrection must have been sincere and, by extension, true. However, this reasoning collapses under scrutiny when juxtaposed with the theological claim in Romans 1:20, which states that non-believers suppress the truth of God’s existence despite “clearly perceiving” it. If one insists that no one would die for a lie, then the Romans 1:20 claim—that non-believers knowingly die denying what they understand to be true—presents an irreconcilable contradiction. Either people can die for what they know is false, or they cannot—but one cannot hold both positions without undermining the argument itself.

By exposing the logical inconsistency, double standard, and rhetorical fallacies in this apologetic framework, we demonstrate that the “apostolic martyrdom” argument is not a sound basis for establishing the truth of Christianity and that the Romans 1:20 claim, if taken literally, is equally self-defeating.

I. Logical Inconsistency: Can People Die for a Lie or Not?

A. The Apostolic Martyrdom Argument

The argument that the apostles would not die for a lie operates on the following logical premise:

- If the apostles knew Jesus had not risen, they would not have willingly suffered martyrdom.

- The apostles did suffer martyrdom.

- Therefore, they must have truly believed in the resurrection, making it more likely to be true.

This argument hinges on the assumption that people do not willingly suffer persecution or death for something they know to be false. Implicitly, it appeals to human rationality and self-preservation, assuming that deception does not extend to the point of self-sacrifice.

B. The Romans 1:20 Claim

Romans 1:20, however, presents the exact opposite claim regarding non-believers:

“For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

Paul argues that non-believers already know God exists but choose to reject this truth, thus making them culpable for their disbelief. If taken literally, this implies that atheists die rejecting what they “know” to be true, which contradicts the fundamental premise of the apostolic martyrdom argument.

C. The Contradiction

If one argues that people do not die for what they know is false, then non-believers cannot be dying while denying a truth they consciously recognize. If, however, non-believers can die while rejecting a truth they know, then the apostles could also have died while defending a belief they knew was false.

Thus, one of these claims must be false:

- (Apostolic Argument): People do not die for lies they know to be false.

- (Romans 1:20 Claim): Non-believers die rejecting a truth they know is true.

Both cannot be true simultaneously.

II. The Double Standard: Selective Application of the Principle

Apologists employ selective reasoning when using martyrdom as evidence. If willingness to suffer and die for a belief proves its truth, then logically:

- The apostles’ willingness to die would prove Christianity is true.

- Buddhist monks’ willingness to die for their faith would prove Buddhism is true.

- Islamic extremists’ willingness to die for their faith would prove Islam is true.

- Atheists’ willingness to face persecution and execution in religious societies would prove atheism is true.

Clearly, this reasoning is flawed. People die for all kinds of deeply held convictions, even those that contradict one another. The willingness to die for a belief only demonstrates sincerity, not truth. The apostles’ martyrdom, therefore, at best proves that they sincerely believed in the resurrection—not that it actually occurred.

However, if Christians dismiss the martyrdom of non-Christian religious figures as insufficient evidence for their truth claims, then they must also dismiss the apostolic martyrdom argument by the same standard. Otherwise, they commit the special pleading fallacy, in which a rule is applied selectively to favor one’s own position while disregarding comparable cases.

III. The Psychological and Sociological Counterargument

Beyond the logical contradiction, there are psychological and sociological explanations for why people might die defending something that is false—even something they secretly know to be false.

A. Groupthink and Cognitive Entrapment

History is replete with examples of individuals who have gone to extreme lengths to maintain a belief system, even when evidence contradicts it. Cults, radical ideologies, and political movements demonstrate that group identity and cognitive entrapment can override self-preservation.

- Members of Heaven’s Gate committed mass suicide believing they would ascend to a higher existence.

- The Jonestown massacre saw over 900 followers drink poison at the command of Jim Jones.

- Doomsday prophets have publicly committed to false predictions and doubled down even after their prophecies failed.

These examples show that people can die for things that are demonstrably false, even when some might secretly suspect they are mistaken.

B. Fear, Loyalty, and the Social Cost of Renouncing Belief

Even if an apostle had harbored doubts, renouncing the resurrection would have meant:

- Losing their entire community

- Betraying close friends and family

- Admitting they had been deceived

- Public humiliation

- Potential execution anyway (as apostates or traitors)

In such cases, it is entirely possible for someone to maintain an outward commitment to a belief, even if they harbor internal doubts.

Thus, the apostles’ willingness to die does not establish certainty that they knew Jesus had risen—it only confirms that they were committed to their cause.

IV. Conclusion: A Call for Logical Consistency

The “apostles would not have died for a lie” argument is logically inconsistent when paired with Romans 1:20. If dying for a belief means it must be true, then the apostles’ deaths prove Christianity only as much as any martyrdom proves its respective religion. If people can die while rejecting a truth they know, then the premise that the apostles’ martyrdom validates Christianity collapses.

A more rational approach is to acknowledge that:

- People can die for false beliefs, whether they know them to be false or not.

- Sincerity does not equal truth.

- Romans 1:20’s claim that non-believers “know” God exists is not tenable if one also holds that people do not die for lies they know to be false.

Ultimately, if one wishes to maintain logical coherence, they must abandon either the apostolic martyrdom argument or the Romans 1:20 claim—because together, they are mutually self-defeating.

The challenge, then, is for believers to critically assess whether they are committed to truth, or merely to arguments that serve their pre-existing convictions.

Leave a comment