The following post employs doctrines related to marriage, divorce and remarriage to demonstrate there exists no coherent standard of hermeneutics available to Christendom.

Marriage, divorce, and remarriage are a perfect case study for how hermeneutical principles get cherry-picked to fit preconceived doctrines. The Bible offers a handful of key texts—Genesis 2, Matthew 5 and 19, Mark 10, Luke 16, Romans 7, 1 Corinthians 7—yet Evangelical apologists arrive at wildly different conclusions. Each camp grabs from the hermeneutical buffet, emphasizing some principles over others to align with their theological or cultural leanings. Here’s a rundown of the major doctrines and the interpretive moves behind them:

Doctrine 1: No Divorce, No Remarriage

Position: Marriage is an unbreakable covenant; divorce is never permitted, and remarriage is always adultery.

Key Texts:

- Genesis 2:24—”A man shall leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and they will become one flesh.”

- Matthew 19:6—”What God has joined together, let no one separate.”

- Mark 10:11-12—”Anyone who divorces his wife and marries another woman commits adultery against her.”

Hermeneutical Principles Employed:

- Literalism: The “one flesh” union and Jesus’ words are taken at face value—no exceptions allowed. Mark’s version, lacking Matthew’s exception clause, is seen as the baseline.

- Authorial Intent: Jesus’ teaching is read as reinforcing God’s original design in Genesis, not adapting to human failure. Divorce is a post-Fall distortion, not a concession.

- Scriptural Harmony: Mark and Luke (no exception clauses) override Matthew’s nuance to present a unified, absolute stance.

- Theological Priority: Marriage reflects Christ’s eternal bond with the church (Ephesians 5:25-32); breaking it defies divine analogy.

Cherry-Picking Move: Ignores Matthew 19:9’s “except for sexual immorality” clause or downplays it as a scribal addition, prioritizing Mark’s stricter wording. Context—like Jewish divorce debates or Greco-Roman customs—is sidelined to keep the rule absolute.

Doctrine 2: Divorce Allowed for Adultery, Remarriage for Innocent Party

Position: Divorce is permitted only for adultery; the “innocent” party can remarry, but the “guilty” party cannot.

Key Texts:

- Matthew 19:9—”Anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery.”

- 1 Corinthians 7:15—”If the unbeliever leaves, let it go… the brother or sister is not bound in such circumstances.”

Hermeneutical Principles Employed:

- Grammatical-Historical Context: “Sexual immorality” (Greek porneia) is tied to Jewish betrothal or Greco-Roman sexual norms, making adultery a legitimate breach.

- Exception Clause Focus: Matthew’s “except” is spotlighted as Jesus’ intentional loophole, distinguishing it from Mark and Luke’s broader audience.

- Analogy of Scripture: 1 Corinthians 7’s “not bound” is linked to freedom to remarry, though it’s debated if Paul means divorce or remarriage.

- Moral Logic: The innocent shouldn’t be punished; remarriage aligns with grace, while the adulterer’s penalty holds.

Cherry-Picking Move: Elevates Matthew’s exception over Mark and Luke’s silence, assuming they’re less detailed, not stricter. Paul’s “not bound” is stretched to mean remarriage, despite ambiguity, while cultural pressures (protecting the “innocent”) shape the outcome.

Doctrine 3: Divorce for Adultery or Abandonment, Remarriage for Both Parties

Position: Divorce is allowed for adultery or desertion by an unbeliever; both parties can remarry.

Key Texts:

- Matthew 19:9 (as above).

- 1 Corinthians 7:15—”God has called us to live in peace.”

Hermeneutical Principles Employed:

- Historical Context: Paul addresses mixed marriages in Corinth; “abandonment” by an unbeliever dissolves the bond fully.

- Pragmatic Interpretation: “Peace” trumps permanence—God doesn’t chain people to broken covenants.

- Progressive Revelation: Jesus refines Mosaic leniency (Deuteronomy 24:1), but Paul adapts it further for new situations, loosening restrictions.

- Redemptive Lens: Grace allows second chances; remarriage isn’t inherently sinful if repentance occurs.

Cherry-Picking Move: Expands porneia beyond adultery to broader covenant-breaking (e.g., abandonment), and assumes “not bound” green-lights remarriage for all. Ignores Mark’s absolute tone and downplays “one flesh” permanence to favor mercy over rigidity.

Doctrine 4: Divorce for Any Reason, Remarriage Allowed

Position: Divorce is permissible for irreconcilable differences (hardness of heart); remarriage is fine for both parties.

Key Texts:

- Deuteronomy 24:1-4—”If a man finds something indecent in her… he writes her a certificate of divorce.”

- Matthew 19:8—”Moses permitted you to divorce… because your hearts were hard.”

- 1 Corinthians 7:10-11—”A wife must not separate… but if she does, she must remain unmarried or else be reconciled.”

Hermeneutical Principles Employed:

- Cultural Relativism: Mosaic divorce laws reflect human reality; Jesus critiques, but doesn’t abolish, the principle.

- Genre Flexibility: Paul’s “remain unmarried” is advice, not command—situational, not universal.

- Ethical Priority: Love and well-being outweigh legalism; staying in toxic marriages contradicts God’s character.

- Silence as Permission: No explicit remarriage ban post-divorce (outside adultery context) implies freedom.

Cherry-Picking Move: Leans on Old Testament leniency and Jesus’ “hardness of heart” comment to justify broad grounds, while brushing off Paul’s “remain unmarried” as optional. Context—like Jesus’ rejection of “any cause” divorce in Matthew 19—is minimized to fit modern sensibilities.

Doctrine 5: Annulment Over Divorce

Position: Some marriages were never valid (e.g., due to fraud, coercion); annulment voids them, allowing remarriage without “divorce.”

Key Texts:

- Matthew 19:6—”What God has joined together…” (implying some unions aren’t God-joined).

- 1 Corinthians 7:39—”A woman is bound to her husband as long as he lives” (if validly bound).

Hermeneutical Principles Employed:

- Theological Nuance: “One flesh” requires true covenant intent; invalid unions don’t count.

- Implied Meaning: Jesus’ silence on defective marriages leaves room for annulment logic.

- Church Tradition: Borrows from Catholic precedent, despite Evangelical aversion, to sidestep divorce stigma.

- Logical Extension: If God didn’t join it, no sin in dissolving it.

Cherry-Picking Move: Infers a loophole from what’s not said, stretching “God has joined” to exclude bad-faith marriages. Ignores explicit divorce texts to craft a workaround that feels less rebellious.

The Buffet in Action

Each doctrine picks its plate:

- Literalists cling to Mark and Genesis, rejecting exceptions.

- Contextualists zoom in on Matthew’s porneia or Paul’s Corinthian chaos, bending rules to fit history.

- Pragmatists prioritize peace or grace, softening absolutes.

- Traditionalists smuggle in annulment to dodge the divorce label.

The principles—literalism, context, harmony, theology—are tools, not laws. Apologists start with their bias (strict morality, pastoral mercy, cultural relevance) and grab the hermeneutical fork that gets them there. Matthew’s exception can be everything or nothing; Paul’s “not bound” can mean freedom or celibacy. The text doesn’t shift—the lens does. It’s a buffet, and the plate’s piled to taste.

A Coherent Meta-Hermeneutics?

To establish a robust, consistent method of biblical interpretation that genuinely reflects the mind of God—assuming the Bible is divinely inspired—requires a “meta-hermeneutics”: a framework above and beyond standard hermeneutical principles that governs how we select and apply them. This isn’t just about picking tools like context, grammar, or analogy of Scripture; it’s about justifying why those tools are the right ones and ensuring they align with God’s intent. Let’s unpack what such a meta-hermeneutics would need, then argue why its absence undermines the idea of a God who wants to be clearly understood authoring the Bible.

What a Meta-Hermeneutics Would Need

A meta-hermeneutics must solve the problem of interpretive chaos—where sincere believers, using the same text, reach contradictory conclusions. To reflect God’s mind, it would require:

- Divine Clarity on Method:

- God would need to embed or reveal an explicit interpretive key within the Bible (or alongside it) that dictates how to read it. This could be a “how-to” manual—say, a canonical statement like “Interpret all my words literally unless metaphor is signaled by genre” or “Weigh historical context above all else.” Without this, humans default to subjective guesswork.

- Example Need: Does “one flesh” in Genesis 2:24 mean a metaphysical bond, a legal contract, or a poetic ideal? A meta-rule would settle it.

- Universal Accessibility:

- The method must be graspable by all intended readers—ancient shepherds, medieval peasants, modern scholars—across time, culture, and intellect. If it’s locked behind elite knowledge (e.g., Greek grammar, ANE history), it fails the “everyman” test of a God who desires relationship with all.

- Example Need: A meta-principle like “The plain meaning to the original audience trumps all” would need to work without PhDs or time machines.

- Consistency Across Texts:

- It must yield coherent results across the Bible’s diverse genres (law, poetry, prophecy, epistles) and apparent tensions (e.g., divorce in Deuteronomy 24 vs. Matthew 19). Contradictory outcomes—like one group banning remarriage and another allowing it—suggest the method’s broken.

- Example Need: A rule like “Later revelation clarifies earlier” would need explicit biblical warrant, not just theological assumption.

- Self-Authentication:

- The meta-hermeneutics should prove itself within the text, not rely on external traditions, reason, or feelings. If God authored the Bible, it should contain internal markers (e.g., “This is how I speak”) that validate the approach, avoiding circular appeals to human authority.

- Example Need: A verse like “My words are spirit and truth; seek my Spirit to understand” (John 6:63, loosely) would need to be explicitly hermeneutical, not inspirational.

- Resistance to Human Bias:

- It must override subjective cherry-picking—where apologists bend texts to fit cultural, moral, or theological preferences. This requires a mechanism to expose and correct deviation, like a divine checksum.

- Example Need: A meta-rule saying “If your reading contradicts my character as love and justice, you’re wrong” would need clear textual grounding and agreement on God’s character.

Can We Build This Meta-Hermeneutics?

The Bible doesn’t deliver. No verse or section lays out a meta-framework. Instead, we get:

- Ambiguity on Method: Jesus says “You search the Scriptures… they testify of me” (John 5:39), but how? Paul praises the Bereans for examining Scripture (Acts 17:11)—with what lens? No manual emerges.

- Genre Confusion: Is Revelation literal or symbolic? Are Psalms doctrinal or emotional? The text assumes we’ll figure it out, but offers no referee.

- Tensions Without Resolution: Matthew’s adultery exception (19:9) clashes with Mark’s absolutism (10:11). Paul’s “not bound” (1 Corinthians 7:15) dangles undefined. No meta-rule arbitrates.

- Dependence on Extras: Serious interpretation leans on history, linguistics, or tradition—tools unavailable to most readers historically. Where’s the built-in equalizer?

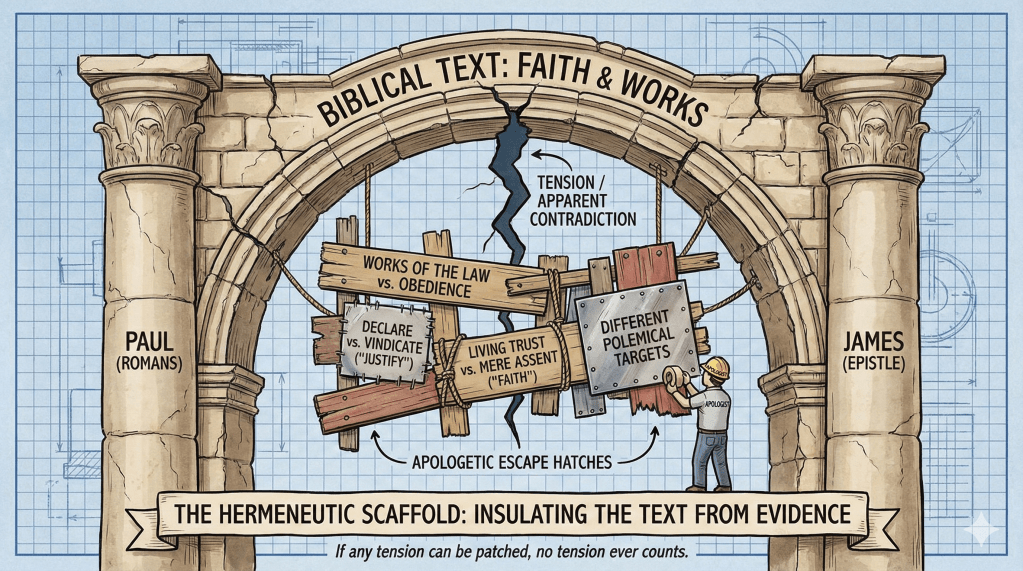

Theologians try to patch this with systems like the historical-grammatical method or the analogy of faith, but these are human constructs, debated endlessly. No consensus emerges because no meta-hermeneutics is self-evident in the text. It’s a free-for-all—each camp claims God’s mind, yet none can prove it.

Why This Absence Undermines Divine Authorship

If God authored the Bible to reveal himself and be understood, the lack of a meta-hermeneutics is a glaring flaw. Here’s the argument:

- Intent to Communicate Implies Clarity:

- A God who wants relationship (e.g., John 17:3—”knowing God is eternal life”) would ensure his message isn’t a riddle without a key. If the Bible’s his word, it should self-regulate interpretation to avoid Babel-like confusion. It doesn’t.

- Human Failure Can’t Explain It:

- Sure, “hardness of heart” or sin might cloud understanding (2 Corinthians 4:4), but that dodge fails if the text itself lacks the tools to cut through. A perfect communicator wouldn’t blame the audience for a flawed medium.

- Contradictory Outcomes Prove Dysfunction:

- Marriage doctrines (no divorce vs. remarriage for all) show the Bible yields opposite readings from honest seekers. A God-authored text should constrain interpretation to one truth, not a buffet. The meta-hermeneutical vacuum lets bias reign.

- Comparison to Human Standards:

- Even human authors—say, a lawmaker—provide preambles or principles to guide interpretation (e.g., a constitution’s intent). The Bible’s silence on method looks sloppy for a divine mind. Why no “Interpret thusly” from an omniscient God?

- Theological Cop-Outs Fall Short:

- Claiming “The Holy Spirit guides” (John 16:13) sounds nice, but why do Spirit-led believers disagree? If the Spirit’s the meta-hermeneutics, it’s inconsistent. Saying “It’s a mystery” or “Wait for heaven” admits the system’s broken now, when it matters.

If God wanted to be understood, he’d rig the game with a meta-hermeneutics—clear, accessible, and ironclad. Instead, we get a text that mirrors human literature: rich, layered, but maddeningly open to spin. The interpretive mess—schisms, sects, and stalemates—suggests no divine mind engineered it for clarity. A God who authored this without a decoder ring either doesn’t care about being known or isn’t there. The evidence leans toward a human product, brilliant but unguided.

Leave a comment