A Non-Testable Claim That Defers Accountability

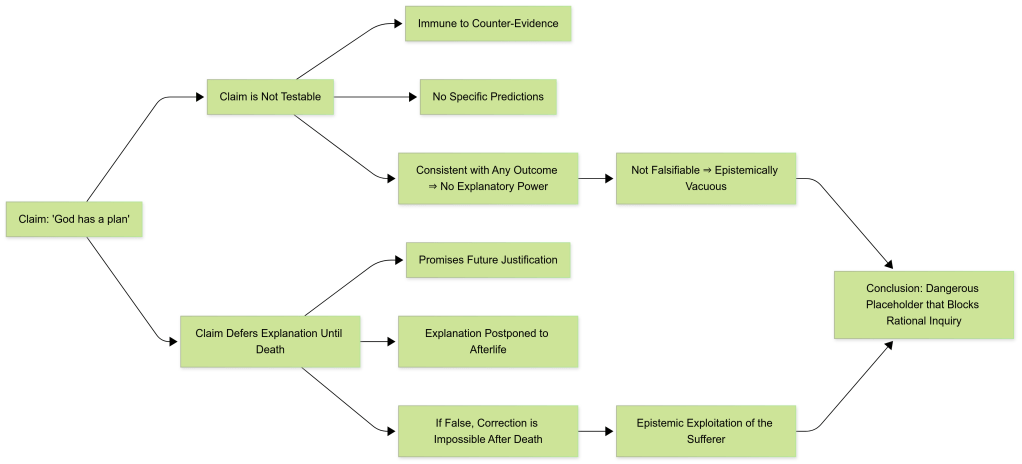

The oft-repeated theistic refrain “God has a plan” is frequently deployed in contexts of extreme suffering, loss, or seemingly senseless events. While it may provide some psychological comfort to those enduring hardship, this proposition warrants serious epistemic scrutiny. In this essay, I will show that: (1) the claim is not testable, and (2) it buys time indefinitely by deferring any explanation until after death, a point at which truth claims can no longer be verified if the theistic narrative turns out to be false.

1. The Claim “God Has a Plan” Is Not Testable

A core principle of any credible explanatory hypothesis is that it should be subject to testability. That is, it must expose itself to the possibility of falsification—if not empirically, then at least rationally or inferentially. The statement “God has a plan”, however, is invulnerable to any observable disconfirmation.

No matter what event occurs—genocide, terminal childhood cancer, earthquakes decimating villages—the believer can always posit that this horror is merely part of a larger, benevolent “plan” beyond our comprehension. This immunity to counter-evidence transforms the claim from a potentially meaningful explanation into a tautology: the plan is good because God is good, and God is good because the plan is good. Such circular reasoning shelters the claim from logical scrutiny.

Furthermore, the lack of temporal constraints or specific predictions means that the “plan” can be adjusted, retrofitted, or abstracted in any direction. This makes the claim more akin to ideological insulation than a genuine explanatory framework. In Bayesian terms, if a hypothesis is consistent with every possible observation, then it adds no weight to any prediction and holds no explanatory power.

2. The Notion Buys Time for Any God to Avoid Explanation

The second major flaw in the “God has a plan” narrative lies in its temporal deferral of justification. It permits believers to say, in effect, “You’ll understand when you die.” That is, the suffering we witness (and endure) on Earth is said to have a hidden purpose that will be revealed posthumously, in an unknowable afterlife realm.

This maneuver defers all burden of proof indefinitely. It buys time for the deity—real or fictional—to avoid addressing pressing questions that a morally or intellectually honest agent would answer now. If the promised vindication or explanation never arrives (because no such afterlife exists), then the sufferer has already endured a life under a comforting lie and is now beyond the reach of correction. This is epistemic exploitation: manipulating cognitive uncertainty in the face of existential fear.

It is akin to an infinite escrow in which no evidence is ever due. An earthly analogy would be a company that promises to pay its investors after death and uses this promise to justify all present losses. No regulatory body would accept such a model, yet many are content to accept this from the supposed Creator of the universe.

Conclusion: The Perils of Non-Falsifiable Consolation

In conclusion, the phrase “God has a plan”, though emotionally appealing, collapses under epistemic scrutiny. It is not testable, because it is consistent with all possible outcomes, and it defers explanatory accountability to a moment that is post-verifiable. As such, it stands as a dangerous placeholder—a means of avoiding rational investigation and silencing the cry of suffering with vague metaphysical promissory notes. If there is no actual plan, the cost of false consolation is borne entirely by the sufferer, who is left without justice, answers, or recourse.

This is not merely a philosophical critique—it is a caution against surrendering our rational faculties to ideas that hide their failure behind death’s door.

◉ The Claim Is Not Testable

Let:

= “God has a plan”

= any empirical event (e.g., suffering, genocide)

= “Claim P is consistent with event E”

= “Claim P is testable”

= “for all”

We assert:

→ The claim is compatible with all events.

Then:

→ There is no possible event that would contradict the claim.

Therefore:

→ The claim “God has a plan” is not testable.

◉ The Claim Defers (Alleged) Explanation Until Death

Let:

= “Justification for P is accessible”

= death

= “Accountability at time t”

= “Revelation of plan at time t”

= “during life”

= “after death”

= “Verification of P is possible”

We observe:

→ No justification or revelation is given during life.

→ Revelation (if any) is said to occur after death.

If post-death (i.e., if there is no afterlife), then:

→ There is no possible accountability at any time.

So the structure permits:

Why Truth Without Divine Hope Is Preferable to False Consolation

The allure of divine hope—of cosmic rescue, eternal life, or a higher plan guiding our suffering—is deeply ingrained in human culture. For many, it offers emotional comfort in the face of loss, uncertainty, and death. Yet comforting illusions, no matter how poetic, remain illusions. Articulating the reality of a world without divine hope is not an act of cruelty, but one of epistemic integrity and respect for personal agency. When we prioritize clarity over consolation, we engage in a project that strengthens the mind rather than pacifies it, and one that elevates responsibility over resignation.

1. False Hope Undermines Epistemic Responsibility

To promote a belief simply because it soothes is to abdicate the principle that belief should be proportioned to evidence. Epistemic responsibility demands that we tether our claims to what can be reasonably inferred, tested, or observed. When a claim lacks sufficient warrant—such as the existence of an afterlife or a benevolent deity orchestrating events—it should be treated with the same skepticism we apply to any unsupported hypothesis. To do otherwise is to break ranks with intellectual honesty, replacing inquiry with fantasy.

False hope, even when sincerely offered, is still a betrayal of truth-seeking. It models and incentivizes poor thinking by suggesting that emotional need legitimizes epistemic shortcuts. The habit of tolerating ungrounded beliefs for comfort seeps into other domains: health, politics, relationships. What starts as a harmless palliative becomes a pattern of self-deception with real-world consequences.

2. Embracing Reality Cultivates Personal Agency

By rejecting divine hope, we are not abandoning meaning; we are reclaiming authorship of it. In the absence of celestial intervention, the weight of responsibility for meaning, compassion, justice, and legacy rests with us. This confrontation with finitude—with a universe that offers no promise of rescue—can be terrifying, but it is also profoundly liberating.

Rather than waiting for a deity to right wrongs or deliver blessings, individuals must act. Agency flourishes when responsibility is owned, not deferred. The grieving mother finds solace not in the fantasy that her child is in heaven, but in the memory of love shared and in the actions she takes to honor that memory. The activist fights not because salvation is guaranteed but because the stakes are real and time is limited.

A world without divine oversight is not bleak; it is unsupervised. And in that unsupervised space, we are free to build meaning from the ground up, with eyes wide open and hands engaged in shaping the only life we know we have.

3. The Moral Cost of Consoling Delusion

Offering false hope, even with the kindest intentions, risks infantilizing the minds of others. It communicates that truth must be softened, that reality is too harsh to be faced, and that deception is a tolerable cost for comfort. But this is not compassion; it is condescension.

To tell someone the truth—that there may be no gods, no afterlife, no cosmic safety net—is not to rob them of hope, but to offer them the dignity of clarity. It is to treat them as reasoning adults capable of facing what is real and choosing how to live with courage and creativity.

Even if one were to believe that some divine hope might be true, promoting it without robust epistemic grounding shifts hope from the hands of human possibility to the speculative unknown. This does not inspire strength; it fosters dependency on what is neither testable nor accountable.

4. Hope Recast: From the Sky to the Soil

To reject divine hope is not to reject hope itself. Rather, it is to relocate it—from heaven to earth, from gods to people, from wishful thinking to committed doing. Hope becomes the honest product of human effort, not the byproduct of supernatural expectation. It is a fragile thing made stronger by its grounding in what is real.

We hope for justice because we organize for it. We hope for healing because we invest in science and compassion. We hope for peace not because a messiah will bring it, but because we teach empathy, resolve conflict, and hold power accountable.

This kind of hope is earned, not given—and it is far more powerful than illusions that fade under scrutiny.

Conclusion: Truth Is the Greatest Respect We Can Offer

Rejecting divine hope is not an act of cruelty; it is a declaration of trust in the human capacity to face reality without retreat. It is a vote for truth over comfort, and for agency over dependency. False hope may pacify, but only truth dignifies. And when that truth is delivered not with scorn but with solidarity, it empowers others to become the very agents of change, compassion, and meaning that a god was never needed to be.

If we must face a godless universe, let us do so not with folded hands and closed eyes, but with open minds, steady hearts, and the resolve to make this single, fleeting life a source of courage, clarity, and connection.

Leave a comment