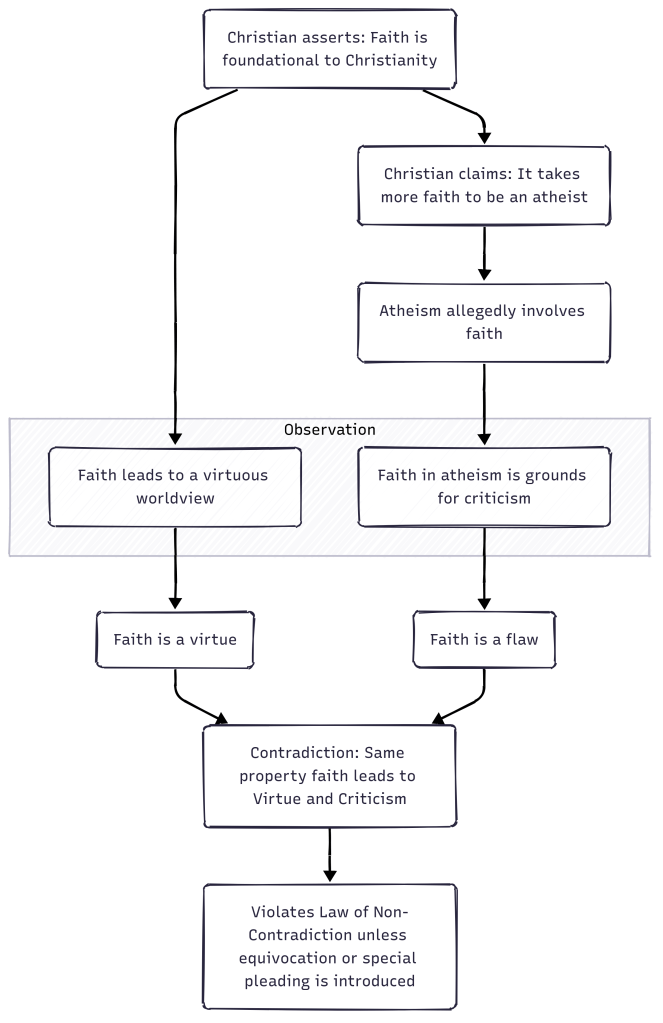

The statement “It takes more faith to be an atheist”—typically made by proponents of a faith-based worldview—presents a profound epistemic contradiction. The contradiction arises when someone champions faith as virtuous in their own worldview, yet uses the alleged presence of faith in others as a criticism.

To further clarify the internal contradiction in this rhetorical maneuver, we can turn to the precision of symbolic logic. By translating the apologist’s assertions into formal statements, we can more clearly expose how the very structure of their reasoning collapses. What appears on the surface to be a clever reversal—accusing atheists of having even more faith—reveals itself, under the lens of logical analysis, to be a case of special pleading and semantic inconsistency. Below is a symbolic breakdown that brings this inconsistency into sharp focus.

Symbolic Logic Formulation

Let us define:

: x operates on faith.

: x holds a virtuous or commendable worldview.

: x deserves criticism for relying on faith.

- Let

- Let

We observe the following assertions by the Christian:

— Christianity is grounded in faith.

— Atheism (allegedly) requires faith.

— Faith is virtuous when applied to their own belief.

— Faith is condemnable when applied to atheism.

From (3) and (4), we derive the logical contradiction:

Contradiction Exposed

From (3) and (4), faith is both:

- a virtue when

uses it:

- a flaw when

uses it:

If the basis for commendation and criticism is the same attribute (faith), then the following is entailed:

— which violates the Law of Non-Contradiction, because no proposition

can simultaneously entail both

and

unless one equivocates on the meaning or value of faith.

In essence:

- If faith is good →

should not be a criticism.

- If faith is bad →

undermines one’s own worldview.

- If one praises faith in self and critiques it in others solely based on the other’s worldview, this introduces special pleading and semantic equivocation.

Conclusion

By simultaneously affirming faith as a virtue in Christianity and a flaw in atheism, the apologist commits a category error and an instance of epistemic hypocrisy. The logic collapses unless the word faith is equivocated or arbitrarily redefined midstream—a fallacy of equivocation that renders the argument invalid.

Chart Notes:

- F(x) = Faith in the Christian worldview

- F(y) = Alleged faith in atheism

- V(x) = Virtuous worldview

- C(y) = Criticized worldview

- The contradiction arises from treating the same property (faith) as both commendable and blameworthy, depending solely on worldview affiliation.

◉ The Incoherence of Praising Faith and Then Weaponizing It

Imagine a man who proudly boasts that his diet consists entirely of chocolate cake. He says, “Cake is the best food—it’s delicious, energizing, and deeply fulfilling.” But the moment he sees someone else eating cake—perhaps a rival—he sneers, “Wow, you eat chocolate cake? That’s disgusting and irrational.” You’d be right to do a double take. Either chocolate cake is a good thing, or it’s not. Praising it when it supports your identity and ridiculing it when someone else partakes is not just hypocritical—it’s logically incoherent.

This, in essence, is the rhetorical move made by many religious apologists who both praise faith as the foundation of their worldview and then attack others by saying, “It takes more faith to be an atheist.” On its surface, this might seem like a clever turn of phrase, but it collapses under basic scrutiny.

Faith as Virtue or Vice?

When the religious believer asserts that their worldview is grounded in faith, they are usually elevating this term. Faith, in their usage, is portrayed as a noble quality—something that rises above the demands of mere evidence and reflects trust in divine truth. It is described as a virtue, a marker of spiritual maturity and commitment.

Yet, in the same breath—or often in the next post—they turn to their interlocutor and say, with a smug tone, “Well, it takes more faith to be an atheist.” This is not intended as a compliment. It is clearly meant as a criticism, suggesting that atheism is even more irrational, even more detached from reason, because it requires even more of the very quality that they just deemed admirable.

This is epistemic sleight of hand.

The Logic Exposed

If we symbolize this, the incoherence becomes evident:

- Let

mean “x holds faith”

- Let

mean “x is virtuous”

- Let

mean “x is culpable or flawed”

When the Christian asserts:

— Faith is good when they have it

— Faith is bad when someone else allegedly has it

This is a direct violation of logical coherence. If faith is good, it cannot simultaneously be bad when exhibited by someone else just because they are not part of your tribe. That is called special pleading—a fallacy in which a principle is selectively applied to favor oneself and disadvantage others.

Faith as a Moving Target

This also raises another question: what do they even mean by “faith”? Is it trust based on some evidence (like trusting a chair will support your weight), or is it belief in excess of available evidence (such as believing in angels, resurrections, or talking snakes)? The ambiguity of the term allows apologists to equivocate—sliding between meanings depending on what will rhetorically benefit them in the moment.

When the atheist speaks of not believing due to insufficient evidence, the apologist often calls this “faith” simply because it does not amount to absolute certainty. But belief in proportion to evidence is not faith—it is rational inference. To call all uncertainty-based belief “faith” is like calling all food “cake” just because both are edible. It’s a category error that falsely equates rational doubt with doctrinal commitment.

The Umbrella Analogy

Imagine someone holding an umbrella and saying, “Carrying an umbrella is a sign of wisdom. It shows I’m prepared for the rain.” Then, as soon as you pull out your umbrella, they say, “Look at you—so scared of a little rain. You must be weak to carry that.” The object in question is the same: the umbrella. What changed is not the thing itself but who was holding it.

In the case of faith, the same object—faith—is either praised or ridiculed depending not on its epistemic quality but on tribal allegiance. That makes it not a reasoned standard but a rhetorical weapon.

Conclusion

To celebrate faith when it props up your own beliefs, and then condemn it when projecting it onto others, is an act of semantic betrayal. It’s not a matter of truth or reason—it’s about tribal loyalty masquerading as epistemology. Until faith is defined clearly and applied consistently, it will remain a rhetorical fog machine—praising and condemning the same thing based not on its value, but on its ownership.

Consistency is the litmus test of intellectual honesty. And any worldview that flips the virtue or vice of faith depending on who’s holding it has already failed.

See also:

Leave a comment