Deductive, Inductive, and Abductive Reasoning

Introduction

Reasoning is the process of drawing conclusions from premises or evidence. Three fundamental methods—deduction, induction, and abduction—form a comprehensive web that allows us to understand and predict phenomena. This article explores these methods using the scenario of rolling a six-sided die, assumed fair unless evidence suggests otherwise. Deduction uses mathematical principles, induction generalizes from 100 die rolls, and abduction infers the most probable explanation for observed outcomes. By examining how these methods interweave, we illustrate their roles in a cohesive reasoning framework.

Defining the Reasoning Methods

Deduction

Deduction reasons from general principles to specific conclusions that follow with certainty. Given true premises, deductive conclusions are logically necessary, often grounded in mathematical models.

Induction

Induction generalizes from specific observations to broader conclusions, typically probabilistic. For example, observing 100 die rolls allows us to estimate probabilities based on frequency patterns.

Abduction

Abduction infers the most likely explanation for observed evidence, synthesizing deductive principles and inductive data to hypothesize causes or predict outcomes.

The Dice-Rolling Scenario

Consider a standard six-sided die with faces numbered 1 through 6. Initially, we assume the die is fair, meaning each face has an equal probability of landing face-up. We will apply deduction, induction, and abduction to understand the die’s behavior and predict outcomes, demonstrating how these methods form a web of reasoning.

Deduction: Mathematical Reasoning

Deduction begins with general principles about a fair die. A six-sided die has six equally likely outcomes: {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. The probability of rolling any specific number, say 6, is:

In rolls, the expected frequency of each number is:

For 100 rolls, the expected number of times each number appears is:

For example, the probability of rolling two 6s in two consecutive rolls is:

These conclusions are certain, assuming the die is fair. Deduction provides the theoretical foundation for evaluating observations and predictions.

Induction: Reasoning from Observations

Induction uses specific observations to form general conclusions. Suppose we roll the die 100 times and observe the following frequencies:

- 1: 15 times

- 2: 14 times

- 3: 16 times

- 4: 15 times

- 5: 17 times

- 6: 23 times

The number 6 appears 23 times, more than the expected 16.67. This suggests a possible bias. The estimated probability of rolling a 6 is:

To assess whether this deviation is significant, we perform a chi-square goodness-of-fit test. The expected frequency per number is 16.67. The chi-square statistic is:

With 5 degrees of freedom (6 sides minus 1), a chi-square value of 3.84 yields a p-value of approximately 0.57, indicating the deviation could be due to chance. However, the higher frequency of 6s suggests a potential bias, warranting further investigation.

Abduction: Reasoning to the Best Explanation

Abduction seeks the most probable explanation for the observed data. Given the inductive evidence (23 sixes) and deductive expectations (16.67 sixes), suppose we also notice a physical imperfection: a chip near the 1 face, opposite the 6.

Consider three hypotheses:

- H1: The die is fair, and the excess sixes are due to random variation.

- H2: The die is biased toward 6 due to the chip, shifting the probability.

- H3: The die is intentionally loaded to favor 6.

Evaluating these:

- H1: The chi-square test (p ≈ 0.57) suggests the fair-die model is plausible, as the deviation is not statistically significant.

- H2: The chip could alter the die’s balance, making 6 more likely. The inductive data (0.23 probability for 6) and physical observation support this.

- H3: A loaded die implies intentional tampering, which is less likely without additional evidence of foul play.

H2 is the most likely explanation, as it accounts for the data, the physical imperfection, and requires fewer assumptions than H3. For the next roll, while any number is possible, 6 is slightly more likely based on the inductive probability of 0.23.

The Web of Reasoning

The three methods form a dynamic web:

- Deduction provides the theoretical model: each face has a

probability, expecting 16.67 occurrences per number in 100 rolls. It sets the baseline for induction and abduction.

- Induction tests this model with data. The 23 sixes suggest a deviation, prompting questions about the die’s fairness.

- Abduction synthesizes the deductive model and inductive data, hypothesizing a bias due to the chip. It predicts that 6 is slightly more likely for future rolls.

The methods interact:

- Deduction to Induction: The fair-die model guides data collection and comparison.

- Induction to Abduction: The observed frequencies provide evidence for abduction to explain.

- Abduction to Deduction: The hypothesis of a biased die suggests a new model (e.g.,

), which can be tested with more rolls.

This cycle continues. For example, if another roll yields a 6, induction updates the frequency (24 sixes in 101 rolls, ), abduction strengthens the bias hypothesis, and deduction adjusts the probability model.

Conclusion

Deduction, induction, and abduction form a comprehensive web of reasoning. In the dice-rolling scenario, deduction establishes the fair-die model, induction reveals a potential bias through data, and abduction explains the bias as a physical imperfection, predicting future outcomes. Together, they provide a robust framework for understanding and predicting the die’s behavior, demonstrating the power of integrated reasoning.

The Dependence of Abductive Conclusions on Inductive Probabilities in Probability Scenarios: A Deeper Look.

Introduction

In probability scenarios, reasoning methods such as deduction, induction, and abduction work together to interpret data and guide decision-making. Abduction, the process of selecting the most likely explanation for observed evidence, relies heavily on the outcomes of inductive reasoning, which establishes a set of probabilities for candidate explanations. This essay explores how an abductive conclusion can only be reached after the inductive conclusion—specifically, the full set of inductively determined probabilities—has been established, and how the act of identifying the abductive conclusion leaves these probabilities unchanged. Using the scenario of rolling a six-sided die, we illustrate this relationship, highlighting the dependence of abduction on induction and the preservation of the inductive framework.

The Dice-Rolling Scenario

Consider a standard six-sided die with faces numbered 1 through 6, initially assumed fair, meaning each face has an equal probability of landing face-up. We roll the die 100 times to collect data, which informs our inductive reasoning, and subsequently use abduction to select the best explanation for the observed outcomes. The interplay between induction and abduction in this scenario demonstrates their sequential and non-disruptive relationship.

Deduction: Setting the Theoretical Foundation

Deduction provides the theoretical model for the scenario. For a fair six-sided die, each face has a probability of:

In rolls, the expected frequency of each number is:

For 100 rolls, the expected number of times each number appears is:

This deductive model serves as a baseline, guiding data collection and providing one possible explanation (a fair die) for later abductive reasoning.

Induction: Establishing the Constellation of Probabilities

Induction generalizes from specific observations to form a set of probabilities for candidate explanations, known as the constellation of probabilities. Suppose we roll the die 100 times and observe the following frequencies:

- 1: 15 times

- 2: 14 times

- 3: 16 times

- 4: 15 times

- 5: 17 times

- 6: 23 times

The number 6 appears 23 times, exceeding the expected 16.67, suggesting a potential deviation from fairness. The inductive conclusion estimates the probability of rolling a 6 as:

From this data, induction constructs a constellation of probabilities for candidate explanations:

- H1 (Fair Die): The die is fair, with

, aligned with the deductive model.

- H2 (Biased Die due to Chip): A physical imperfection (e.g., a chip near face 1, opposite 6) causes a bias, with

.

- H3 (Loaded Die): Intentional tampering causes a bias, also with

.

To evaluate the deviation, we perform a chi-square goodness-of-fit test. The expected frequency per number is 16.67. The chi-square statistic is:

With 5 degrees of freedom (6 sides minus 1), a p-value of approximately 0.57 indicates the deviation could be due to chance, but the elevated frequency of 6s suggests a potential bias. This constellation of probabilities (H1, H2, H3) represents the inductive conclusion, forming the comprehensive rational epistemic position that abduction relies upon.

Abduction: Selecting the Best Explanation

Abduction selects the most likely explanation from the inductive constellation, incorporating both the inductive probabilities and the deductive model, along with contextual evidence. The abductive conclusion can only be reached after the inductive conclusion has established the full set of probabilities for candidate explanations.

In the dice scenario, the inductive constellation includes:

- H1: Fair die,

.

- H2: Biased die due to chip,

.

- H3: Loaded die,

.

Suppose we observe a physical imperfection: a chip near the 1 face, opposite the 6. Abduction evaluates the hypotheses:

- H1: The chi-square test (p ≈ 0.57) suggests the fair-die model is plausible, as the deviation is not statistically significant.

- H2: The chip could shift the die’s balance, making 6 more likely. The inductive probability (

) and physical observation support this.

- H3: A loaded die implies intentional tampering, which is less plausible without evidence of foul play.

Abduction selects H2 as the most likely explanation, as it aligns with the inductive probability (), is consistent with the deductive framework (deviation from fairness), and is supported by the contextual evidence (chip). For decision-making, such as predicting the next roll, 6 is slightly more likely (

).

Crucially, this abductive selection does not alter the inductive constellation. The probabilities ( for H1,

for H2 and H3) remain unchanged, as abduction merely chooses the most probable hypothesis for practical purposes without modifying the empirical data or derived probabilities.

Why Abduction Depends on the Inductive Conclusion

The abductive conclusion requires the inductive conclusion—the full set of probabilities—to be established first because:

- Empirical Foundation: The inductive constellation provides the empirical probabilities (e.g.,

) that abduction uses to evaluate hypotheses. Without these, abduction lacks data to assess plausibility.

- Comprehensive Candidates: The constellation includes all plausible explanations (H1, H2, H3), ensuring abduction considers the full range of possibilities. For example, H1 relies on the deductive probability (

), while H2 and H3 stem from the observed data (

).

- Contextual Integration: Abduction integrates the inductive probabilities with contextual evidence (e.g., the chip) and the deductive model, but the probabilities themselves are fixed by induction.

In any probability scenario, such as a medical trial or weather forecasting, induction first establishes probabilities (e.g., drug efficacy or

chance of rain). Abduction then selects the best explanation (e.g., drug mechanism or atmospheric condition) based on these probabilities and additional context, but the probabilities remain unchanged.

Preservation of Inductive Probabilities

The act of identifying the abductive conclusion does not affect the inductive constellation. In the dice scenario:

- The inductive probabilities (

for H1,

for H2 and H3) are derived from the observed frequencies (23 sixes in 100 rolls).

- Abduction’s selection of H2 (biased die) is a pragmatic choice for prediction or action, driven by the probability (

) and the chip’s evidence, but it does not alter the frequencies or probabilities for H1 or H3.

- If another roll yields a 6, induction updates the constellation (e.g., 24 sixes in 101 rolls,

), and abduction may re-evaluate, but the original inductive probabilities remain intact until new data is incorporated.

This preservation ensures the inductive conclusion remains the stable, empirical foundation, representing the rational epistemic position, while abduction serves as a decision-making tool.

The Web of Reasoning

The dependence of abduction on induction fits into a broader web of reasoning:

- Deduction provides the theoretical model (e.g.,

), guiding induction and informing abduction’s baseline (H1).

- Induction establishes the constellation of probabilities (H1, H2, H3), which abduction requires to select the best explanation.

- Abduction synthesizes deductive and inductive inputs, choosing H2 without altering the inductive probabilities, and may suggest a refined deductive model (e.g.,

).

This sequential relationship—deduction guiding induction, induction producing the constellation, and abduction selecting from it—ensures a robust reasoning process.

Conclusion

In probability scenarios, the abductive conclusion can only be reached after the inductive conclusion establishes the full set of probabilities for candidate explanations. The dice-rolling scenario illustrates this: induction derives probabilities ( for a fair die,

for biased or loaded die), and abduction selects the most likely explanation (biased die due to chip) based on these probabilities and contextual evidence. The act of selecting the abductive conclusion does not affect the inductive probabilities, preserving the empirical foundation. This relationship highlights the critical role of induction in providing the epistemic groundwork for abduction’s pragmatic decisions, ensuring a comprehensive and rational approach to reasoning.

Epistemic Integrity in Abductive Reasoning:

The Resurrection Case Study

Introduction

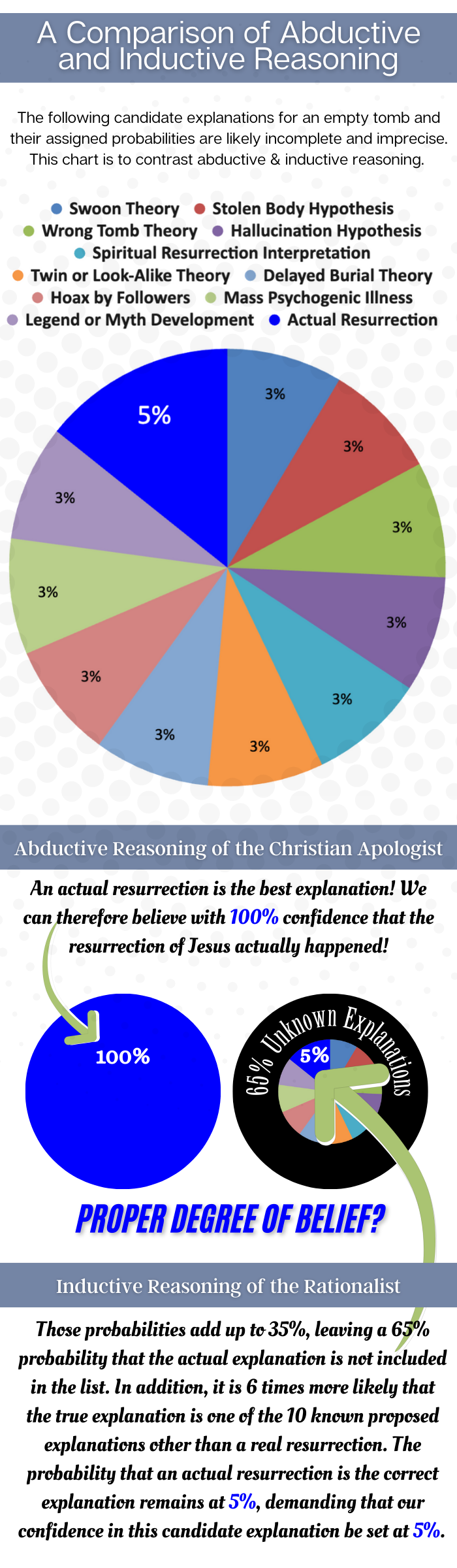

Reasoning plays a critical role in evaluating extraordinary claims, such as the resurrection of Jesus, a cornerstone of Christian belief. Abductive reasoning, which selects the “best explanation” for an alleged empty tomb from available options, is often employed to argue for the resurrection’s plausibility. However, this essay contends that an abductive conclusion must maintain epistemic integrity by reflecting the low probability (pedogogicaly assigned 5%) established through inductive reasoning, rather than assuming full certainty (100%). Using the provided graphic and content, we explore how the inductive conclusion—establishing a probability distribution—must precede the abductive selection, and how identifying the best explanation does not alter the inductively determined probabilities.

The Resurrection Scenario

The resurrection of Jesus is presented as the “best explanation” for the empty tomb. Alternative explanations include the Swoon Theory, Stolen Body Hypothesis, Wrong Tomb Theory, Hallucination Hypothesis, Legend or Myth Development, Spiritual Resurrection Interpretation, Twin or Look-Alike Theory, Delayed Burial Theory, Hoax by Followers, and Mass Psychogenic Illness. The graphic suggests a hypothetical probability distribution: each alternative has a 3% probability (totaling 30%), the actual resurrection has a 5% probability, and unknown explanations account for 65%. This distribution serves as the inductive foundation for abductive reasoning.

Induction: Establishing the Probability Distribution

Inductive reasoning analyzes observed data—historical accounts, testimonies, and cultural developments—to establish a probability distribution for candidate explanations. The graphic below pedogogically assigns:

- Alternative Explanations: 30% combined probability, with each of the ten alternatives (Swoon Theory, Stolen Body Hypothesis, etc.) at 3%.

- Actual Resurrection: 5% probability as a single explanation.

- Unknown Explanations: 65% probability, representing unformulated or undiscovered possibilities.

This constellation of probabilities represents the inductive conclusion, reflecting the rational epistemic position. The 5% probability for the resurrection is the highest individual probability among known explanations, but it is overshadowed by the 30% cumulative probability of alternatives and the 65% for unknowns. This distribution must be fully established before abduction can proceed, as it provides the empirical basis for evaluating explanations.

Abduction: Selecting the Best Explanation

Abduction selects the most probable explanation from the inductive distribution, integrating contextual evidence (e.g., early Christian testimonies) and the deductive baseline (e.g., the possibility of a miracle). The graphic and content suggest that Christian apologists favor the actual resurrection (5%) as the “best explanation,” arguing it is more plausible than the 3% alternatives due to its coherence with historical claims. We will accept this for the sake of argument.

However, the abductive conclusion can only be reached after the inductive probability distribution is established. The 5% probability for the resurrection, derived from inductive analysis, indicates its relative plausibility among known explanations. Contextual factors—such as the rapid spread of belief or the empty tomb—may support this choice, but the probability remains 5%, not 100%. The act of selecting the resurrection as the best explanation does not increase its probability or alter the distribution (30% alternatives, 65% unknowns). Instead, it reflects a decision to prioritize this explanation for a deeper exploration or action (if one is forced), while acknowledging its limited epistemic weight. However, the credence one can assign to the candidate explanation of the redemption must remain at 5% for the rational mind, despite its #1 ranking among candidate explanations.

The probabilities pedogogically assigned to candidate explanations above are inexact and serve only to highlight the common fallacy of moving from identifying the most probable known candidate explanation (5% in this case) to an unjustified high belief approximating 100% that this candidate explanation is the actual explanation.

Maintaining Epistemic Integrity

Epistemic integrity requires that the abductive conclusion align with the inductive probability (5%) rather than jumping to 100% certainty. Several factors support this stance:

- Cumulative Probability of Alternatives: The 30% combined probability of alternative explanations (each at 3%) exceeds the 5% for resurrection. Ignoring this aggregate probability skews the evaluation, overemphasizing the “best” explanation without considering its competitors collectively.

- Unknown Explanations: The 65% probability for unknowns highlights the vast range of unformulated possibilities. Dismissing this majority probability risks overconfidence, assuming current explanations are exhaustive.

- Historical Precedent: Past paradigm shifts (e.g., germ theory replacing miasma theory) demonstrate that unknown explanations often emerge, suggesting the 65% is a rational acknowledgment of epistemic limits.

- Overconfidence Risk: Elevating the resurrection to 100% certainty based on its 5% probability misrepresents “best” as “certain,” undermining rational scrutiny. The graphic’s contrast between inductive (95% alternatives/unknowns) and abductive (100% resurrection) reasoning underscores this fallacy.

Thus, the abductive conclusion must emphasize the low 5% probability to maintain integrity, reflecting the inductive distribution rather than claiming absolute certainty.

The Impact of Identifying the Abductive Conclusion

Identifying the resurrection as the best explanation does not affect the inductively determined probabilities. The distribution—5% for resurrection, 30% for alternatives, 65% for unknowns—remains intact post-abduction. This preservation is critical:

- The 5% probability for resurrection is a fixed inductive outcome, derived from historical data and analysis.

- Selecting it as the best explanation is a pragmatic choice for belief, not a revision of the probabilities.

- If new data emerges (e.g., additional testimonies), induction updates the distribution, but the abductive act itself has no retroactive effect.

For example, if another account reinforces the resurrection, induction might adjust its probability (e.g., to 6%), but the original 5% stands until then. Abduction’s role is to extract a decision from the constellation, not to redefine it.

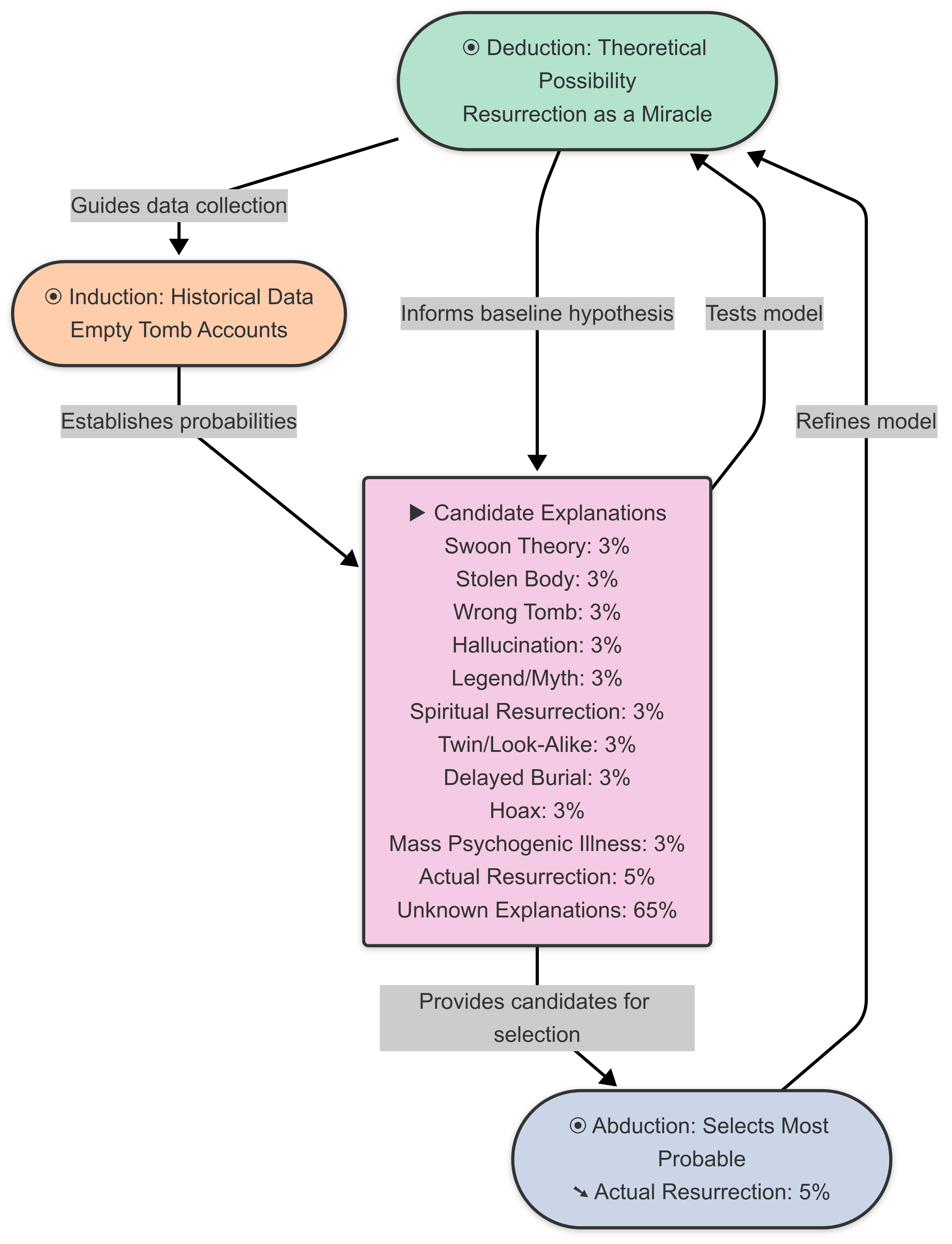

The Web of Reasoning

This relationship fits into a broader reasoning framework:

- Deduction provides the theoretical possibility of a miracle, guiding inductive data collection.

- Induction establishes the probability distribution (5% resurrection, 30% alternatives, 65% unknowns), which abduction relies upon.

- Abduction selects the resurrection (5%) as the best explanation, informed by inductive probabilities and deductive context, without altering the distribution.

The sequential dependency (induction precedes abduction) and the preservation of probabilities ensure a rational approach.

Conclusion

In the resurrection case study, the abductive conclusion—selecting the actual resurrection as the best explanation—must reflect the inductive probability of 5% to maintain epistemic integrity. This selection can only occur after the inductive distribution (5% resurrection, 30% alternatives, 65% unknowns) is established, and it does not alter the original probabilities. The graphic highlights the danger of jumping to 100% certainty, a fallacy that overlooks cumulative alternatives and unknown explanations. By grounding abduction in the inductive 5%, we preserve rational humility, ensuring extraordinary claims like the resurrection are evaluated with appropriate skepticism and evidence, rather than overconfidence.

Leave a comment