◉ Induction Necessarily Precedes Deduction in Human Epistemology

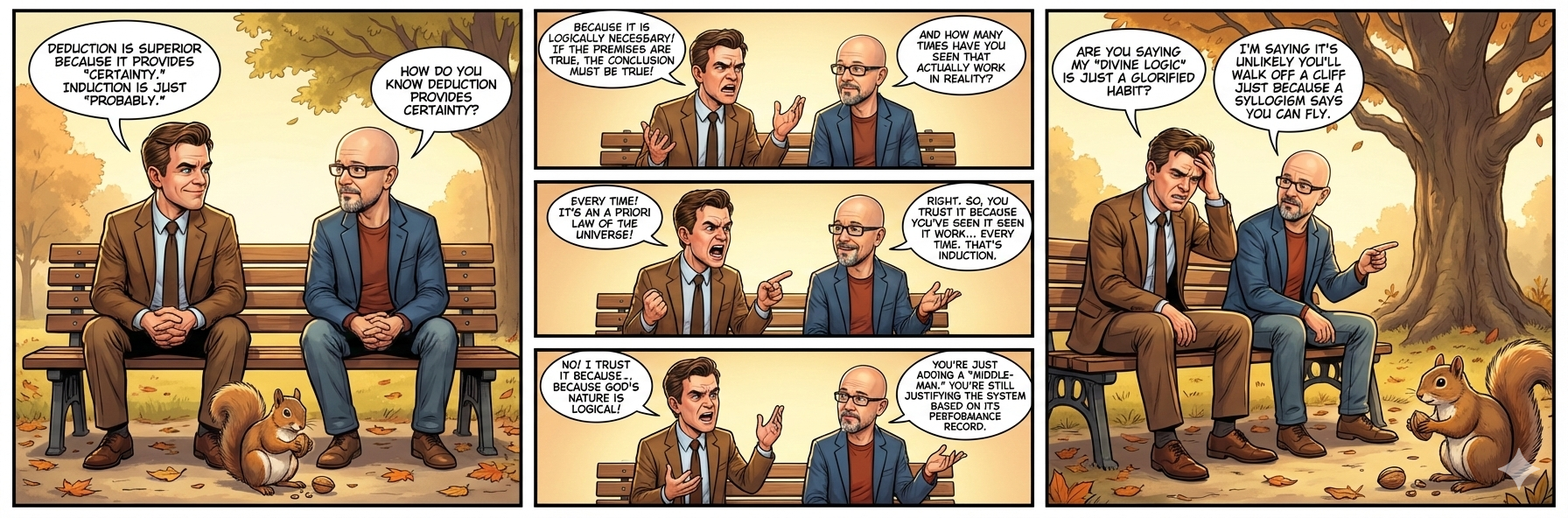

The long-standing hierarchy between induction and deduction is often misrepresented. Many classical philosophers treated deduction as epistemically superior—definitive, certain, and self-justifying—while relegating induction to a weaker, probabilistic status. But this perception ignores a crucial point: deductive reasoning is not self-authorizing. It is, in fact, epistemically dependent on inductive reasoning for its initial justification and continual validation within human cognition. This essay defends the claim that induction necessarily precedes deduction in any real, functional epistemology, particularly in human minds.

◉ 1. Rationality as an Instrument, Not a Presupposition

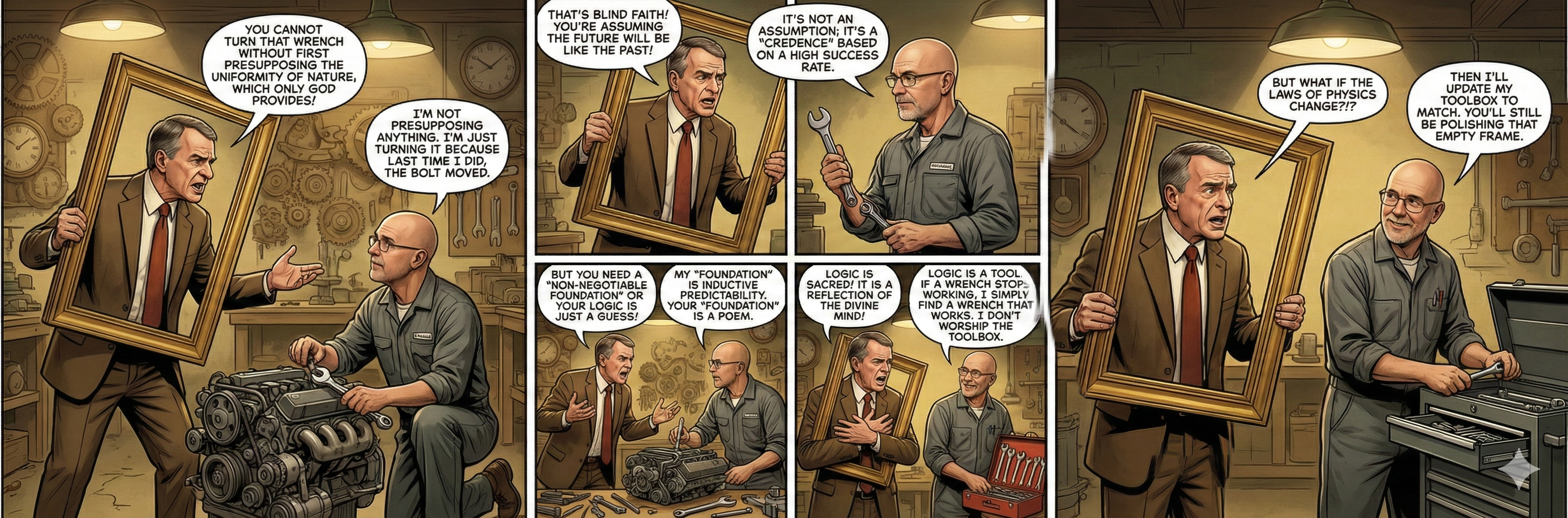

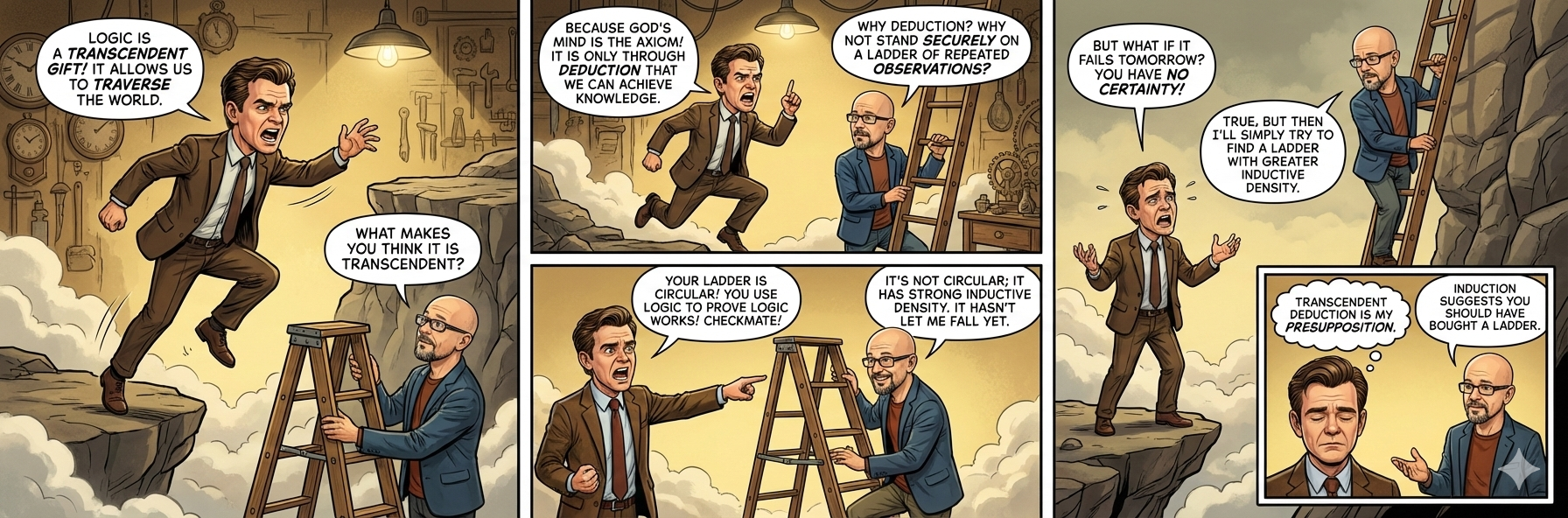

Before we consider the relationship between deduction and induction, we must clarify what it means to “follow what works.” To endorse rationality is not to assume it as a presupposition. Instead, it is to adopt it provisionally based on its demonstrable success across contexts.

To “follow what works to the degree that it works for as long as it works” is not arbitrary, nor is it circular. It is a description of pragmatic rationality: beliefs are accepted with credence proportionate to the weight of the evidence, and updated when new evidence arises. There is no sacred axiom, no inviolable belief—only empirically grounded inferences. What “works” is determined not by fiat but by testing, prediction, and performance.

This stance, far from being nihilistic or arbitrary, reflects epistemic humility. It recognizes that all claims—even claims about logic itself—must prove their worth inductively before they can be treated as reliably applicable.

◉ 2. Deduction Is Not Self-Justifying

Deductive systems (e.g., formal logic, mathematics) function within syntactic frameworks defined by axioms and rules of inference. These systems can yield valid conclusions from given premises, but they do not generate confidence in themselves. They must be shown to reliably correspond to reality, and that confidence must come from induction.

Why should we trust modus ponens or transitivity? Not because of some a priori revelation, but because they have shown, through experience, to produce successful predictions and consistent internal coherence. In other words:

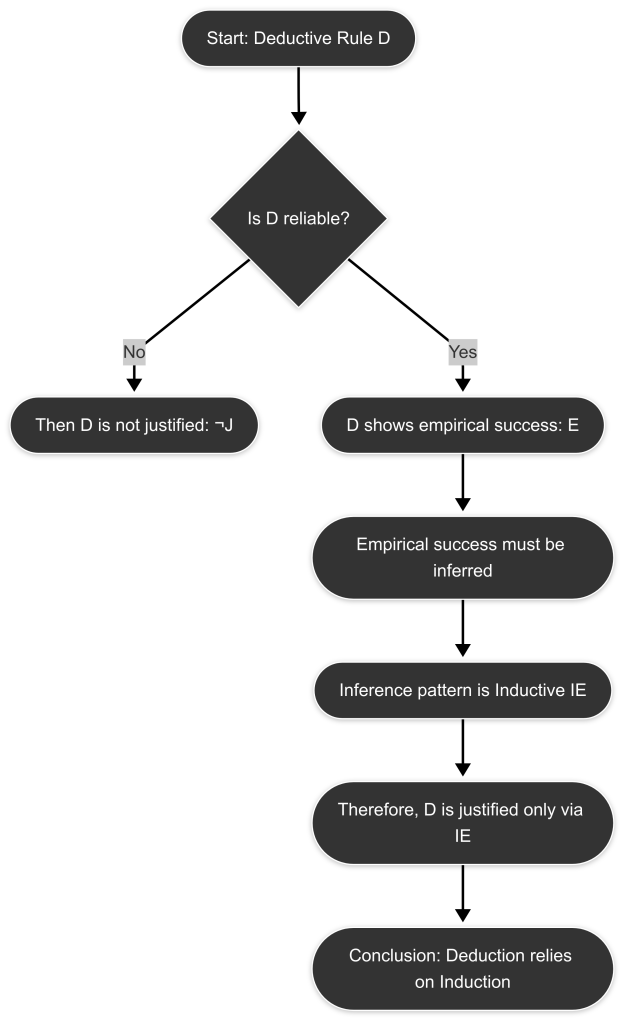

We infer the reliability of deduction through the inductive observation of its repeated success.

Therefore, the human confidence in deduction is always posterior to induction.

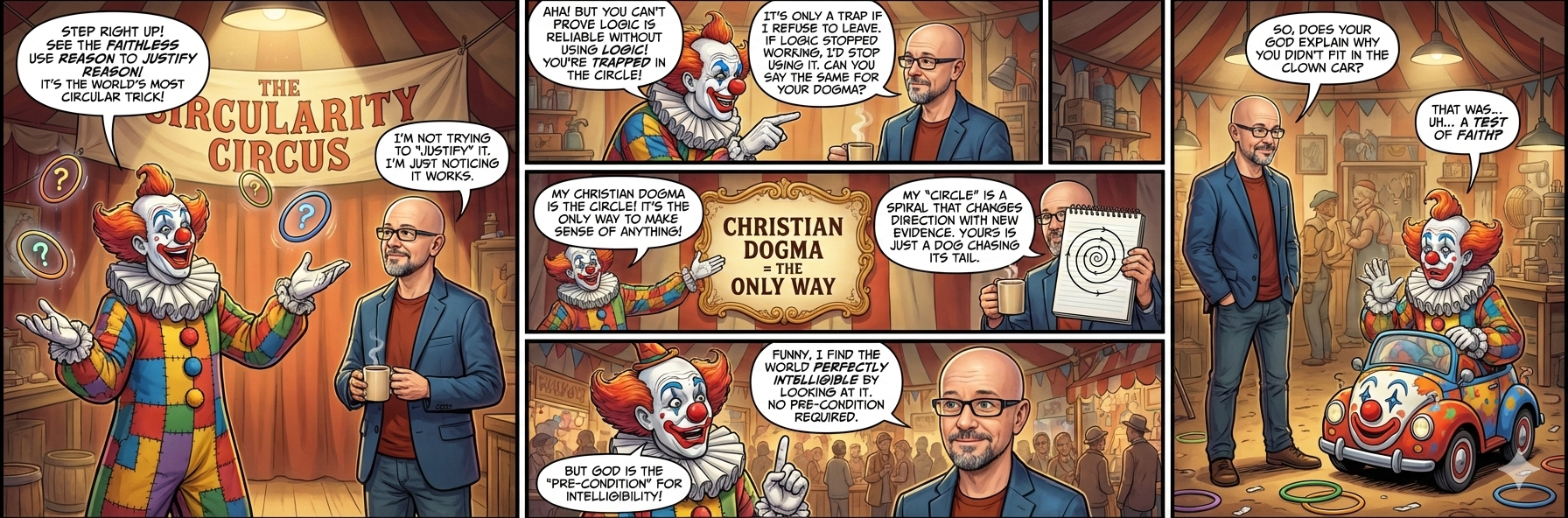

◉ 3. The Circularity Problem and Its Escape

Presuppositionalists like Van Til argue that all reasoning is circular—that logic, uniformity, and interpretation all presuppose fixed, non-negotiable foundations. But this assumes that tentative belief and presupposition are functionally identical. They are not.

- A presupposition is a belief held prior to and independent of evidence, often immune to revision.

- A credence, by contrast, is a degree of belief scaled to evidence, and it is always revisable.

Inductive rationalism avoids vicious circularity by refusing to treat any proposition as sacrosanct. It says: “We will use logic, but only because it works. If it fails, we stop using it.” That is not circular—it is empirical and self-correcting.

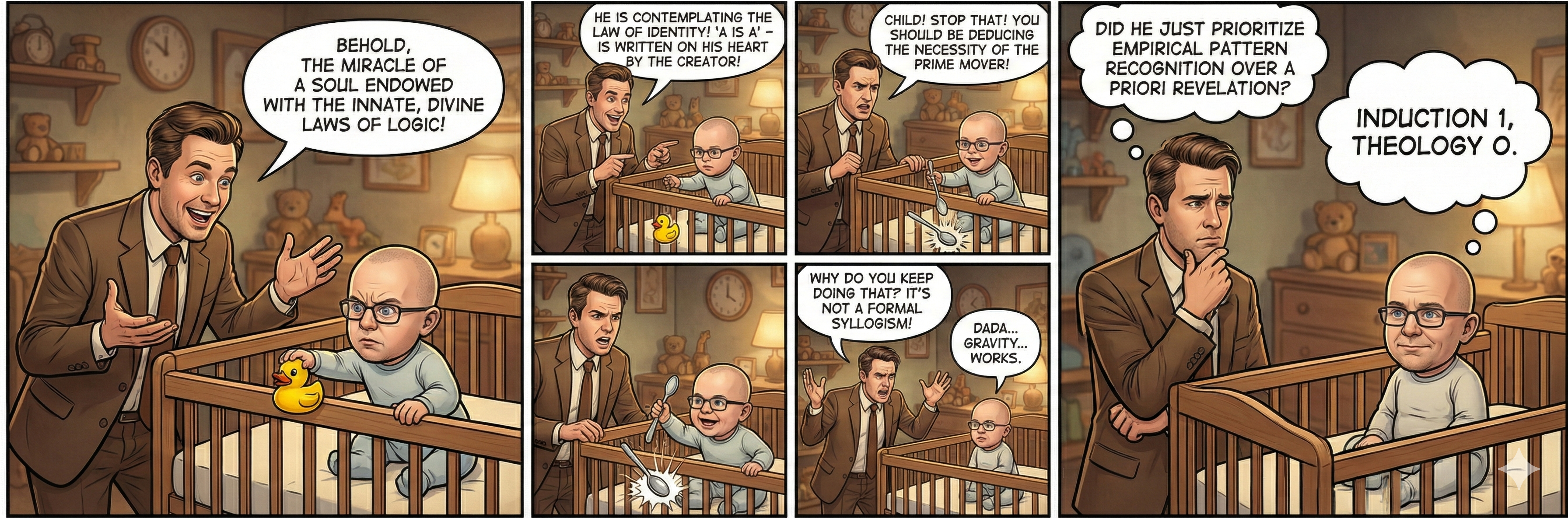

◉ 4. Human Minds Are Not Formal Systems

Finally, the necessity of inductive precedence becomes clear when we consider how humans learn:

- Infants learn through pattern recognition, repetition, and trial-and-error—induction, not deduction.

- The rules of logic are not innate; they are abstracted from the patterns of reliable reasoning observed in experience.

- Even deductive inference itself is often taught inductively—with examples and generalizations.

Human cognitive architecture is not deductive by default. It is adaptive, feedback-driven, and experiential, which means it is fundamentally inductive.

◉ Conclusion

To ask, “Why follow what works?” is to misunderstand the structure of rational epistemology. There is no transcendent justification required for rationality—its record of success is justification enough. The only alternative is to follow what doesn’t work—and history has shown where that leads.

Deduction is a powerful instrument—but it is not foundational. Induction precedes it, authorizes it, and, if necessary, revokes it.

Rational belief is a degree of belief that maps to the degree of the relevant evidence.

This principle is inductively validated—and from it, all other reasoning must follow.

To formalize this relationship, we can construct a symbolic logic system demonstrating that deductive reasoning requires inductive support.

❖ Formal Setup

We’ll use the following symbolic abbreviations:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Material implication (“if…then…”) | |

| Existential quantifier (“there exists…”) | |

| Universal quantifier (“for all…”) | |

| Semantic entailment | |

| Therefore | |

| Syntactic derivability (provable from axioms or rules) |

❖ Argument in Symbolic Logic

P1:

P2:

P3:

C1 (from P1 and P3):

C2 (from P2 and C1):

C3 (summarizing the inference):

❖ Conclusion

This demonstrates that deduction is not epistemically autonomous. It must be validated through the inductive inference that:

Hence, the epistemic justification of deduction is logically downstream of induction, not co-equal or foundational in isolation.

Critiques of the Article Above:

Raul #1 — {Based on a Facebook Exchange}

That’s why I used the word precondition. Squabbling over words isn’t going to get you out of the critique.

Induction is still something that’s called into question, so appealing to that in order to justify the rest of the system also begs the question.

The reason why the critique does not apply to the Christian traditions is because the foundation of the Christian traditions is the main thing about them. You can’t apply a critique that says “your worldview does not have a transcendent foundation” to a worldview that has a transcendent foundation.

Christianity doesn’t ground logic, regularity, or inference “better”, it’s that since the Bayesian system is also called into question, appealing to it would be begging the question.

You said I never demonstrated why a non-transcendent source fails. I did, I said that they are called into question, so appealing to them would be begging the question.

Induction is also called into question. Appealing to it is begging the question.

“Induction is provisionally trusted because it worked in the past and continues to out perform rivals…” The question still stands, what about the past necessitates that the future will be the same. Appealing to the past will again beg the question. Another question is that how does one even know that the past is real and not illusory with the appearance of age?

You say that your system only provides probabilities, and the question is, why even trust probabilities? If you say that it’s going to work, why trust what works as opposed to what doesn’t?

Your system cannot stand without the granting of your assumptions/axioms/preconditions/presuppostions. It has to beg for them not to be called into question. This does not apply to the Christian traditions because the worldview can appeal to the transcendent foundation to justify the preconditions in question. Calling into question the transcendent foundation will assume the aforementioned axioms which are already justified in the Christian system.

Let’s address your objections point-by-point, each in reference to the content and structure of the article “Induction Precedes Deduction.” I’ll aim for clarity and rigor, especially where epistemic justification is in question.

◉ 1. On “Precondition” vs “Precedence”

You’re right to note that word choices matter. But the critique misunderstands the use of “precedes” in the article. Induction precedes deduction not as a metaphysical “precondition,” but as an epistemic one. That is, our confidence in deduction arises from the inductive observation of its reliability.

This is not a semantic dodge. To precede epistemically is to be the basis upon which justification is formed, not necessarily a metaphysical foundation. The claim is observational and cognitive—not ontological.

◉ 2. Is Appealing to Induction Circular?

You claim that appealing to induction is circular because induction is “called into question.” But that’s a misunderstanding of the difference between presupposing and provisionally adopting based on performance.

To clarify:

- Begging the question involves assuming what you’re trying to prove.

- Inductive rationality, as outlined in the article, does not assume induction’s truth—it tests it. Induction is not immune to revision. It is retained because it works better than alternatives—predictively, reliably, and revisably.

This is the opposite of circular. It’s conditional trust based on track record—a process you already use every day, unless you treat seatbelts, antibiotics, or GPS with the same skepticism.

◉ 3. Why Trust What Works?

You ask: “Why trust what works as opposed to what doesn’t?”

This question misconstrues the nature of epistemic responsibility. If two methods are proposed—one that consistently generates success (e.g., navigating, engineering, medicine), and one that doesn’t—the burden is on you to explain why one should favor failure, or neutrality, over success.

To “trust what works” is not a blind leap—it is a provisional policy grounded in feedback loops. It’s the default behavior of all adaptive systems: test, refine, repeat. The alternative is to adopt methods without demonstrable merit—which is not rational by any serious epistemic standard.

→ Examining the Logic and Consequences of Trusting What Does Not Work

The principle “follow what works” is grounded in feedback-sensitive epistemology. It simply means: if a method or belief consistently yields accurate predictions or successful outcomes, we give it higher credence. This is not circular reasoning—it is self-correcting pragmatism. Now, let’s critically evaluate the inverse of this approach: trusting what does not work.

◉ Logical Breakdown of “Trusting What Fails”

Let’s formalize the contrast between two attitudes toward belief systems:

- S1: Adopt beliefs that reliably produce successful predictions or outcomes.

- S2: Adopt beliefs that reliably fail to produce successful predictions or outcomes.

If S1 is pragmatically justified by success, S2 is necessarily undermined by its own track record. To prefer S2 over S1 is to say:

“I know this method fails, and I prefer it because it fails.”

This collapses into epistemic nihilism or irrational defiance. It becomes either:

- Self-refuting (you are using a failed method to determine what counts as success), or

- Anti-realist in a pathological way (you abandon any notion of correspondence between belief and observable reality).

◉ Consequences of Trusting What Doesn’t Work

- Catastrophic Practical Outcomes

Trusting what does not work results in:- Ineffective medicine (e.g., bloodletting over antibiotics),

- Engineering failures (e.g., ignoring physics in structural design),

- Dangerous decisions (e.g., rejecting weather data before a hurricane).

- Immunity to Correction

If one adopts a system that fails but protects itself from scrutiny (e.g., “God’s ways are higher than ours” or “faith, not evidence”), then failure is no longer evidence against the system. This is confirmation bias weaponized. - Epistemic Paralysis

If we cannot favor what works over what doesn’t, then no belief is better than any other. You have no grounds to prefer:- Science over superstition,

- Medicine over prayer,

- Evidence-based belief over faith-based assertion.

- Undermining All Learning and Progress

The entire edifice of human knowledge—from language acquisition to quantum physics—rests on iterating what works. To abandon this is to reverse evolution’s method: trial, error, retention. It would amount to anti-epistemology.

◉ Summary

To reject “trust what works” is to embrace epistemic suicide.

It severs the feedback loop that allows beliefs to track reality. Such a stance not only rejects what has shown itself useful, but actively prefers what fails—a position that is:

- Logically incoherent (because it uses success/failure criteria to argue against success),

- Empirically indefensible, and

- Psychologically suspect, as it often arises from dogmatism or despair rather than reason.

In contrast, trusting what works—to the degree that it works, for as long as it works—is the only epistemic posture that allows for correction, adaptation, and growth. Anything else is not just irrational. It’s unlivable.

◉ 4. “The Past Might Be Illusory”

You suggest that appealing to the past might be illegitimate if the past is illusory. But this is a universal skeptical problem—not one uniquely threatening to the inductive system.

The same skeptical move can call into question:

- The validity of Scripture (perhaps it’s divinely falsified).

- The revelation of God (perhaps you hallucinated it).

- The existence of other minds, even God’s.

If skepticism about the past discredits empirical methods, it discredits all methods—including your own tradition. Inductive rationality is simply more honest about this risk and adapts to new evidence, rather than retreating into unverifiable metaphysics.

◉ 5. Does the Christian “Transcendent Foundation” Escape Critique?

You claim Christianity escapes critique because it grounds everything in a transcendent foundation. But that’s not an escape—that’s a relocation of the problem:

- Why should we believe your “transcendent foundation” exists?

- Why trust your method of accessing its truth (Scripture, prayer, etc.)?

- Why trust those justifications and not those of other faiths with contradictory doctrines?

You don’t escape epistemic circularity by declaring a fixed point—you just disguise it. And worse: you inoculate that fixed point from revision, which is exactly what the article criticizes. Christianity treats its axioms as immune, whereas inductive rationality allows all beliefs to be questioned, tested, and updated.

◉ 6. On Probabilistic Systems

You argue that probabilistic reasoning is insufficient. But real-world decision-making requires probabilistic reasoning:

- Medicine relies on risk assessment.

- Engineering on safety margins.

- Weather forecasts on probability distributions.

There is no certainty. That’s not a flaw—it’s honesty. If the best you can do is say, “Christianity offers certainty,” the question becomes: Does that certainty correspond to anything real?

Confidence without evidence is not epistemic virtue. It’s dogmatism.

◉ Summary

Your objection hinges on this: “Induction is also called into question.” But the article’s claim is that everything is called into question, including deduction and divine revelation. Induction earns its place not by assumption, but by demonstrated performance.

To say “the past might be illusory” or “we can’t trust what works” is a universal solvent. If you apply it to induction, you must apply it to everything—including your God. The difference is: induction welcomes the test. Christianity silences it by calling its foundations transcendent.

If one system is falsifiable and the other isn’t, which is more likely to be honest?

Raul #2 — {Subsequent Comment}

It’s not a real critique to say “it’s not a presupposition, it’s an axiom” for example. The argument is that when that category of thing is called into question, the system now has no valid appeal to justify them.

Either way, saying that induction is not presupposed is simply untrue. From a simple google search: “Yes, inductive reasoning relies on a presupposition, often referred to as the Uniformity Principle or the Uniformity of Nature. This principle assumes that the future will resemble the past, the unexamined will resemble the examined, and that nature is generally uniform.”

You raise a familiar objection, and it deserves a careful response—especially since the terms presupposition, axiom, and principle often get blurred in debates like this. Let’s disentangle your claim and clarify the article’s position on the status of induction, particularly in relation to the so-called Uniformity of Nature (UoN).

◉ 1. Presupposition ≠ Provisional Principle

You quote the Uniformity of Nature and say this is a “presupposition,” suggesting that induction must be assumed prior to evidence. But this conflates two very different epistemic postures:

- A presupposition, in the Van Tilian or foundationalist sense, is immune to revision. It is not evaluated or adopted because it works, but held as non-negotiable—often because it is claimed to be revealed or divinely grounded.

- A provisional principle or working assumption (like UoN) is adopted tentatively because of its repeated success in generating accurate predictions, technological utility, and explanatory power.

So yes, we provisionally use the principle of uniformity in inductive reasoning—but we do so only because it works, not because we treat it as epistemically sacred. This is a critical distinction. If the world showed radical discontinuity tomorrow, we would adjust our priors. That’s not dogma. That’s responsive rationality.

◉ 2. The Error of Google-Search Epistemology

You cite a basic web search to claim that induction “relies on a presupposition.” But note:

- That statement often reflects a descriptive summary of classical philosophy, not an endorsement of the presuppositionalist critique.

- More recent epistemology and Bayesian philosophy of science treat the UoN as a model-dependent regularity—one that is not metaphysically assumed, but statistically reinforced.

So, quoting a dictionary or an introductory website doesn’t resolve the issue. What matters is how the principle is operationalized in actual epistemic practice:

- We do not assume that the future must resemble the past.

- We infer, from observed regularities, that probabilistic expectations are more warranted than arbitrary guesses.

This is not logical certainty—it’s reasoned confidence based on performance.

◉ 3. What Happens When the Uniformity Is “Called into Question”?

You assert that once the uniformity principle is questioned, “the system has no valid appeal to justify it.” But that critique is only compelling if you demand perfect, transcendental justification.

The article explicitly rejects that standard. It defends a fallibilist, performance-based epistemology:

- No principle is above being called into question.

- All principles are retained only so long as they continue to work across contexts.

- Epistemic justification is always evidential and revisable—not foundational in the rigid sense you seem to require.

In short: your critique demands that induction defend itself like a religious doctrine. But that’s precisely the epistemology we reject.

◉ 4. Your Position Commits a False Equivalence

You treat all assumptions as functionally equal—whether they’re faith-based, revelatory, or empirically tested. But there’s a stark difference between:

- Unfalsifiable metaphysical assumptions (e.g., “God guarantees nature’s uniformity”),

- and

- Empirically reinforced provisional assumptions (e.g., “Nature has been observed to behave uniformly, so we tentatively expect that to continue”).

One is closed to revision; the other is open, testable, and probabilistically constrained.

To claim they’re equivalent because both involve “assumptions” is like saying that trusting a parachute because it’s been tested hundreds of times is no different from jumping with a backpack labeled “Hope.”

◉ 5. Summary

Any expectation of uniformity is:

- Provisional, not absolute.

- Justified by track record, not revelation.

- Open to revision, not dogmatically fixed.

(If the mind detects no uniformity—if, for example, outcomes appear random, uncorrelated, or contradictory—then the mind inductively registers that fact as well. The absence of uniformity is itself a detectable pattern, leading to low or near-zero credence in future regularities of that kind. This demonstrates that induction does not require an a priori commitment to uniformity; instead, it flexibly adjusts to the presence, absence, or degree of observed regularity. Inductive reasoning functions like a feedback-sensitive system: it increases expectation where stability is observed, and decreases it where chaos or inconsistency prevails. At no point does it require a fixed presupposition—because its epistemic power lies in its conditional responsiveness, not in any claim of metaphysical certainty. To presuppose uniformity would be to commit to it regardless of experience, which is exactly what inductive reasoning avoids.)

This is why the article says induction is not a presupposition in the presuppositionalist sense. It’s not a sacred axiom—it’s an empirically justified heuristic, constantly updated.

In contrast, presuppositionalist foundations claim immunity from scrutiny. That’s not superior—it’s epistemically inert.

Leave a comment