The Argument from Reason:

Steel-manning and Rebuttal

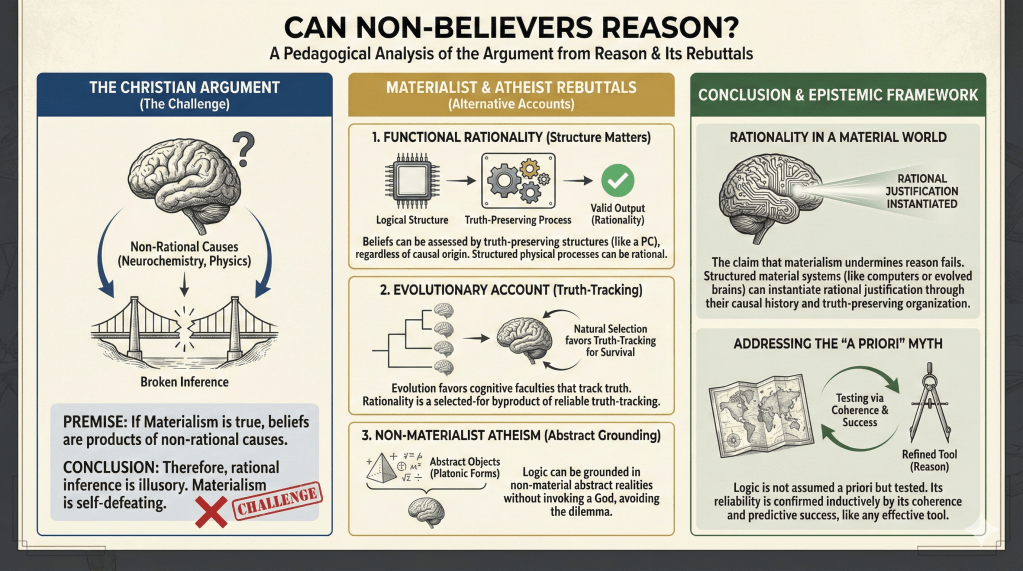

The Christian Argument: Reason and the Challenge to Materialism

The Christian argument, often associated with C. S. Lewis and other proponents of the so-called “Argument from Reason,” begins with an observation about the nature of rational inference. It points out that certain mental processes, such as drawing conclusions from premises in a logically valid way, seem to preserve truth. For example, if one accepts that all men are mortal and that Socrates is a man, then one must conclude that Socrates is mortal. This relationship between premises and conclusion is not arbitrary; it is what philosophers call veridical: it preserves truth across possible worlds.

This argument claims that materialism, which holds that everything that exists is fundamentally physical or reducible to physical processes, cannot account for this kind of truth-preserving rational inference. According to this view, if materialism is true, all mental states, including beliefs, are the products of non-rational causes such as neurochemical reactions and physical forces. Consequently, reasoning itself would be illusory, as no actual “reasons” would exist—only causes.

This position is commonly formulated as a syllogism:

P1: No belief is rationally inferred if it can be fully explained in terms of non-rational causes.

P2: If materialism is true, then all beliefs can be fully explained in terms of non-rational causes.

Conclusion: Therefore, if materialism is true, no belief can be rationally inferred.

In symbolic logic, this can be expressed as:

Where: means belief x can be fully explained by non-rational causes.

means belief x is rationally inferred.

represents the proposition that materialism is true.

This leads to a corollary:

In other words, if materialism is true, no belief is the product of rational inference. Since belief in materialism itself would fall under this critique, materialism would be self-defeating: the materialist has no rational grounds to hold materialism.

Proponents of this argument often further contend that reason involves a kind of normativity or aboutness that cannot be reduced to physical interactions. The claim is that in a purely material world, the mere causal history of a belief cannot confer its rational justification or its truth-preserving quality. Rational justification requires participation in logical relations that are independent of mere causation.

Materialist and Atheist Rebuttals

Several rebuttals have been proposed to this argument, each seeking to show that materialism can account for rational inference or that the argument from reason does not necessitate theism.

1. Functional Rationality and Truth-Preserving Structures

One line of response argues that although beliefs may arise through non-rational causes, they can still be assessed for their rationality by appeal to truth-preserving structures such as the laws of logic. The analogy of a computer (see the expanding section below) is often invoked: such a machine may lack consciousness or rational agency, yet can output valid conclusions when operating according to the rules of logic.

Thus, the materialist can hold:

P1: Beliefs can arise through non-rational causes yet be evaluated for rationality through truth-preserving structures.

P2: Under materialism, cognitive systems can generate and verify beliefs using these structures.

Conclusion: Therefore, materialism does not preclude rational inference; it grounds rationality in functional, truth-preserving processes.

Symbolically:

Where: means belief x is produced by a truth-preserving structure.

means belief x can be verified as rational.

Natural language explanation: This argument asserts that what matters for rationality is not the cause of a belief but whether the belief can be checked and validated against objective standards such as logic. Even if beliefs are generated by physical processes, they can still participate in logical structures that preserve truth.

An Argument from the Logical Output of Computers

An Argument from the Logical Output of Computers: Countering the Claim That Rational Justification Cannot Arise from Material Causes

Proponents of the Argument from Reason assert that rational justification requires participation in logical relations that are independent of mere causation. They claim that physical interactions, by themselves, cannot confer normativity, aboutness, or truth-preserving quality. However, we can construct a counter-argument based on the logical output of computers and other purely material devices that process information according to physical laws.

Syllogistic Formulation

P1: Computers are purely material systems whose outputs result entirely from physical interactions governed by causal laws.

P2: Computers can produce outputs (e.g., proofs, calculations, valid logical inferences) that are truth-preserving and conform to the standards of rational justification.

P3: If purely material systems can produce outputs that conform to standards of rational justification, then participation in logical relations can arise from causal processes.

Conclusion: Therefore, participation in logical relations can arise from causal processes, and rational justification does not require independence from material causation.

Symbolic Logic

Definitions:: x is a purely material system.

: x produces output via causal physical processes.

: x produces output that conforms to logical relations (truth-preserving).

: x provides rational justification.

Premises:

Conclusion:

Annotation:

There exists at least one purely material system (e.g., a computer) whose causally determined outputs conform to logical relations and provide rational justification.

Clear-Language Summary

Computers are entirely physical systems: every bit flip, signal transmission, or logic gate operation is the result of causal interactions among material components. Yet, when properly programmed and functioning correctly, computers produce outputs that conform to the highest standards of logical rigor. They generate valid deductions in formal systems, verify theorems, and solve complex mathematical problems—tasks that embody truth preservation.

This demonstrates that participation in logical relations and the production of rationally justified outputs do not require a non-material substrate or independence from causation. Rather, truth-preserving processes can emerge from and depend entirely on physical causation, as long as those processes are structured appropriately (e.g., according to the rules of logic encoded in software and hardware design).

In this way, normativity and aboutness can be understood as properties of structured causal systems that map inputs (e.g., premises) to outputs (e.g., conclusions) in accordance with abstract rules—not as properties that require separation from material causation.

Conclusion

The logical outputs of computers illustrate that participation in truth-preserving logical relations can and does arise from purely causal, material interactions. Therefore, the claim that rational justification requires independence from material causation is not supported: structured material systems can instantiate rational justification through their causal history.

2. The Evolutionary Account of Rationality

Another rebuttal, advanced by philosophers such as Jerry Fodor, appeals to evolutionary theory. The core idea is that natural selection favors cognitive faculties that track truth because true beliefs contribute to survival and reproductive success. Under this view, evolution provides a naturalistic explanation for why our cognitive apparatus tends to produce true beliefs.

This can be framed as:

P1: Evolution selects for cognitive faculties that promote survival through tracking truth.

P2: Cognitive faculties that track truth can produce rational inferences.

Conclusion: Therefore, evolution can give rise to faculties that support rational inference, even under materialism.

Symbolically:

Where: represents evolution by natural selection.

means cognitive faculty x tracks truth.

means cognitive faculty x supports rational inference.

Natural language explanation: Evolution has shaped our minds so that they are generally reliable in tracking the truth because true beliefs enable us to interact effectively with our environment, avoid danger, and achieve survival. Thus, rationality is a byproduct of evolutionary pressures that favor truth-tracking cognitive systems.

3. Non-Materialist Atheism

A further rebuttal points out that rejecting materialism does not entail accepting theism. One could adopt a non-materialist form of atheism that posits the existence of abstract objects, such as Platonic forms, to ground reason and logic without invoking a deity.

This position can be structured as:

P1: Reason and logic may be grounded in non-material abstract structures without invoking God.

P2: Atheism is consistent with the existence of non-material abstract structures.

Conclusion: Therefore, the existence of reason does not entail theism; it may entail non-materialist atheism.

Symbolically:

Where: means non-material abstract structures exist.

means reason is grounded.

means atheism is true.

Natural language explanation: This view holds that the existence of non-material realities, such as mathematical truths or logical laws, does not necessitate the existence of God. One could be an atheist and accept these abstract objects as the grounding for reason and logic. This position avoids the alleged dichotomy between materialist atheism and theism.

Conclusion

The argument from reason is an ambitious attempt to show that materialism is self-defeating because it undermines the possibility of rational inference. However, materialist and atheist responses challenge this argument by offering alternative accounts of how reason could exist and function within a material or naturalistic framework. These include appeals to functional structures, evolutionary accounts of truth-tracking cognitive faculties, and non-materialist forms of atheism that posit abstract objects without invoking God.

The chart below highlights the relative strength of each rebuttal along multiple criteria.

| Feature | #1: Functional Rationality | #2: Evolutionary Account | #3: Non-Materialist Atheism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explains truth preservation | High | High | High |

| Compatible with materialism | High | High | Low |

| Avoids metaphysical inflation | High | High | Low |

| Handles normativity/aboutness | Medium | Medium | High |

| Empirical support | High | High | Medium |

| Simplicity/Parsimony | High | High | Low |

Each of the rebuttals—particularly the functional rationality account—demonstrates that the argument from reason fails to undermine materialism, atheism, or non-belief. The functional rationality rebuttal shows decisively that rational justification can arise from material causal processes when those processes are structured in truth-preserving ways, as exemplified by computers and other physical systems that produce valid inferences. Far from requiring non-material or divine grounding, rationality can emerge from and operate within purely physical systems. The evolutionary and non-materialist atheist responses further reinforce this conclusion by offering naturalistic and non-theistic frameworks that successfully account for truth preservation and normativity. The claim that materialism is self-defeating collapses under the weight of these robust alternatives, leaving the argument from reason without force against either materialism or atheism.

◉ Addressing the Claim: “[IQ] testing only establishes the veracity of individual reasoning, not reasoning itself.”

The False Necessity of A Priori Rationality Assumptions

The quoted assertion rests on the claim that rationality or logic must be accepted a priori—that is, before any testing can occur—and that testing cognition can only affirm the validity of individual reasoning, not reasoning itself. This response will demonstrate that this claim is mistaken. Specifically, it falsely assumes a foundationalist model of epistemology in which all reasoning must be grounded in a prior and unquestionable acceptance of logic, rather than in a coherentist or inferentialist framework in which even logic itself is subject to empirical justification via inductive success.

1. Testing of Reasoning Is Not Limited to the Individual

The first error in the quote lies in the notion that the testing of cognition only establishes the veracity of individual reasoning. This misunderstands how reliability is assessed.

When we test reasoning—say, through a syllogistic exercise, a scientific inference, or a Bayesian judgment—we are not simply testing a person but also the inference structure itself. For instance, if deductive reasoning consistently produces results that are both non-contradictory and empirically confirmed, we accumulate evidence that the form of reasoning (not just its instance) is reliable.

This parallels how we assess measurement tools:

- A single thermometer may yield an accurate temperature. But when many thermometers, across varied conditions, yield results that cohere and correlate with other measurements, we affirm not just the reliability of the individual instruments but also the underlying principle of thermometry.

- In the same way, coherence and predictive success across many applications of deductive and inductive reasoning reinforce confidence in reasoning systems themselves.

Hence, the reliability of reasoning is not limited to isolated cognition. It is statistically and structurally testable.

2. No Need for A Priori Acceptance of Logic

The claim that logic must be “accepted a priori” to make testing possible reflects a misunderstanding of how reasoning emerges. The notion of “a priori” here is doing the wrong kind of work.

Yes, when we engage in reasoning, we use logical operations (e.g., modus ponens). But this is not the same as claiming they must be dogmatically assumed or accepted as transcendent truths. Instead:

- We adopt patterns of inference provisionally, then assess their utility, coherence, and predictive power.

- This is especially true for non-deductive forms of reasoning, like induction or abduction, which are not “self-justifying” but are supported by their historical and empirical success.

This aligns with the Bayesian model of belief: All beliefs—including belief in the utility of logic—are held with a degree of confidence, and this confidence is updated based on observed outcomes. If modus ponens ever failed spectacularly in practice, our credence in its universal applicability would justifiably fall. Thus, even logic is not held a priori in the rigid Cartesian sense but is justified a posteriori by the world’s apparent consistency with it.

3. Circularity Avoided Through Epistemic Coherence, Not Foundational Axioms

Some might object: “But isn’t it circular to test reason using reason?” This objection is misplaced because it treats all justification as foundationalist—i.e., dependent on an unquestionable base. But coherentist models resolve this: what matters is not a foundation, but whether the network of beliefs cohere, produce consistent results, and explain observations better than alternatives.

Here’s the key point:

- Logic and reason are not assumed true but treated as working hypotheses that are repeatedly confirmed through application.

- They succeed because they map well onto the world, not because they are declared inviolable beforehand.

To use an analogy: just as a map is not assumed accurate a priori but judged by how well it gets you to your destination, logic is judged by how reliably it produces accurate beliefs and useful predictions.

4. Human Rationality Is Tested, Not Assumed

Finally, the notion that “testing can only begin after logic is accepted” is factually incorrect. In cognitive science, developmental psychology, and comparative cognition, logic is precisely what is being tested. We do not assume infants, animals, or even humans have valid reasoning. We test it:

- Through puzzles, inference problems, probabilistic games, and decision-making experiments.

- If their reasoning conforms to expected norms (e.g., transitive inference, avoidance of contradiction), we say reasoning appears present and reliable.

- If not, we either adjust our models or downgrade the assessed reliability.

Thus, logic is not the precondition of testing; it is often the object of testing.

Conclusion: The Quoted Claim Confuses Use with Justification

To summarize:

✓ We can test reasoning itself, not just individual instances of reasoning.

✓ Logic does not need to be assumed a priori. It is justified through performance and coherence, not blind faith.

✓ The appearance of circularity dissolves when we reject foundationalism and adopt a coherentist epistemology.

✓ Logic, like any other cognitive tool, earns its place inductively—by showing it works.

Rationality, then, is not sacrosanct dogma. It is a tool, continually refined through experience, shaped by results, and held with the same kind of credal humility we apply to all other beliefs.

Other Examples:

Here are several other systems in which both the specific elements and the underlying system itself are tested interdependently, much like how reasoning structures and individual reasoning instances can be simultaneously assessed:

◉ 1. Scientific Measurement Instruments

Example: Testing a new blood glucose meter

- Element-level: Each meter’s individual readings are tested on specific patients.

- System-level: Agreement among different meters across time, contexts, and populations validates the principles of glucose measurement (e.g., the enzymatic reaction system or electrochemical sensor reliability).

- Co-dependence: Repeated convergence and predictive utility bolster trust in both individual meters and the entire biochemical detection system.

◉ 2. Statistical Models

Example: Linear regression for economic forecasting

- Element-level: One instance of a regression model may accurately predict GDP from unemployment data.

- System-level: When many regression models across fields repeatedly yield valid, non-spurious predictions, this supports the general methodology of linear regression and inferential statistics.

- Co-dependence: We don’t assume regression as infallible but test its structure each time it’s used—and this recursive testing refines the overall method.

◉ 3. Judicial Systems

Example: A specific court ruling vs. the legal reasoning system

- Element-level: A particular verdict may seem just or unjust.

- System-level: The consistency of judgments across similar cases and jurisdictions can indicate whether legal reasoning, precedent-based adjudication, and interpretive canons are reliable.

- Co-dependence: A failure in the consistency of verdicts may impugn the underlying system, prompting reform or refinement.

◉ 4. Language Acquisition Testing

Example: Testing whether a child understands subject-verb agreement

- Element-level: A child’s specific grammatical error is one data point.

- System-level: Patterns across many learners (e.g., overgeneralization of “goed” for “went”) test broader linguistic theories such as universal grammar or statistical learning models.

- Co-dependence: Theory and instance correct each other—flaws in either push refinement in both.

◉ 5. Cryptographic Protocols

Example: Testing a specific encryption algorithm

- Element-level: A single algorithm may resist brute-force attacks today.

- System-level: When hundreds of algorithms are subjected to ongoing penetration testing and formal analysis, we develop confidence not just in the instances, but in the underlying assumptions of mathematical complexity theory and randomness generation.

- Co-dependence: Failures expose vulnerabilities in both specific implementations and sometimes in the broader computational assumptions.

◉ 6. Medical Diagnosis Frameworks

Example: Using DSM-5 for diagnosing depression

- Element-level: One diagnosis may seem accurate.

- System-level: Consistency of diagnosis across practitioners and correlation with treatment outcomes reinforce confidence in the framework itself (DSM-5 criteria, psychiatric categories).

- Co-dependence: Failures at the level of individual diagnoses can undermine confidence in the nosological structure itself.

◉ 7. Educational Assessment Systems

Example: A specific student’s SAT math score

- Element-level: One student’s score offers partial information about their math ability.

- System-level: Large-scale reliability, fairness, and predictive validity of the test (e.g., SAT scores predicting college success) test the testing methodology.

- Co-dependence: Systemic biases or low predictive validity across populations force us to re-evaluate both test items and the underlying theory of academic measurement.

These examples all mirror the epistemic structure highlighted in the core argument: utility, coherence, and predictive success justify confidence in systems, rather than any a priori declaration of their infallibility. The notion that reasoning, logic, or any evaluative framework must be assumed rather than tested is thus undermined by precedent across scientific, legal, linguistic, and technological domains.

See Also:

➘ https://freeoffaith.com/cs-lewis/#AFR

Leave a comment