How Christian Belief Produces the Very Assumptions It Pretends to Test

Christianity, like many ideologies, does not begin with a neutral survey of reality and then build a belief system from the ground up. Instead, it begins with belief—and then bleeds its presuppositions into every interpretive layer of perception. This essay unpacks how Christianity not only operates with a full set of theological assumptions, but uses those very assumptions to measure the “truth” of reality. In doing so, Christianity sets up a circular epistemic system in which alignment is not discovered but manufactured. The result is a self-affirming feedback loop: belief generates the assumptions, the assumptions define the interpretive criteria, and the belief is then confirmed by its own children. The ideology bleeds into the epistemic filter, shaping what counts as evidence, coherence, or even plausibility.

This is what we mean by a bleeding ideology: one in which the belief is not constrained by reality, but instead seeps outward into the entire method of interpreting reality—so that the original belief is never in serious danger of disconfirmation.

◉ 1. The Belief Comes First

At the heart of Christianity is not a method but a message—a claim about God, salvation, human nature, and destiny. For many believers, these claims are seldom initially accepted because of carefully weighed evidence, but because of trust in an authority (parent, pastor, scripture, community, inner experience). From that starting point, these beliefs begin to bleed outward.

For example:

✓ If one believes that a loving, personal God exists, then suffering must have a reason.

✓ If one believes humans are sinful, then guilt becomes confirmation.

✓ If one believes the Bible is God’s word, then internal consistency becomes evidence of divine authorship.

But in each case, the conclusion is embedded in the framing. Belief is not evaluating evidence—it is constructing what counts as evidence.

◉ 2. Assumptions as Epistemic Filters

The bleeding ideology manifests in the form of loaded assumptions. These are not peripheral to Christian theology—they are its scaffolding:

- A personal God exists and is involved.

- Humans are morally fallen and in need of redemption.

- The Bible is a reliable revelation.

- There is a heaven and hell.

- History is moving toward divine fulfillment.

Each of these is treated not as a hypothesis to be tested, but as a framework within which everything else is evaluated. Reality is not a neutral field for inquiry—it is a puzzle with only one correct solution predetermined by the framework. Any evidence contrary to these assumptions is dismissed (e.g., “That’s just human pride”) or reinterpreted to fit (e.g., “God’s ways are higher than ours”).

◉ 3. Alignment That Isn’t Discovery—It’s Engineering

Believers often claim that Christianity “aligns with reality,” but this is deeply misleading. The alignment is not the result of empirical matching but interpretive manipulation. What counts as “reality” has already been filtered and redefined according to the assumptions birthed by belief.

Example: The problem of suffering.

- A neutral observer might say: Suffering suggests either an indifferent universe or at least a god who is not omnibenevolent.

- The Christian, starting from the assumption that God is loving, interprets suffering as:

- A test of faith

- A tool for sanctification

- The result of human sin

- A mystery within God’s plan

In this way, suffering—potentially disconfirming—gets co-opted as confirmatory. This isn’t a passive alignment with reality. It’s a redrawing of reality so the ideology can survive.

◉ Other Assumptions

Christian Assumptions Shaping Their Perception of Reality

The following list outlines core assumptions that form the foundation of the Christian worldview, shaping how Christians interpret reality and align their ideology with it. These assumptions are derived from common Christian theological frameworks, primarily rooted in biblical teachings and traditional doctrines. Each assumption includes two plausible statements: the first reflects how a Christian might express the assumption, and the second illustrates a misguided assessment where a Christian evaluates Christianity’s truth by circularly comparing it to the reality shaped by the assumption itself.

➘ Existence of a Personal God

- Assumption: A singular, personal, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent God exists who created and sustains the universe. This God is actively involved in the world and human affairs, possessing a will and intentions for creation.

- Plausible Statement: “God is not some distant force; He’s a loving Father who created everything and cares deeply about my life, guiding me every day.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity must be true because I feel God’s presence in my life, and only a personal God like ours could make the world feel so purposeful.”

➘ Objective Moral Realm

- Assumption: There exists an objective moral order, grounded in God’s nature or divine commands, that defines good and evil independent of human opinion. Evil and goodness are real, metaphysical realities, not merely subjective or cultural constructs.

- Plausible Statement: “Right and wrong aren’t just opinions; God’s law shows us what’s truly good, and evil exists when we turn away from His standards.”

- Misguided Assessment: “The world’s evil proves Christianity is right, because only our faith explains why people act against God’s clear moral rules.”

➘ Reality of Sin

- Assumption: All humans are inherently sinful, having fallen from an original state of perfection due to disobedience (original sin). Sin separates humans from God and is the root cause of moral and physical corruption in the world.

- Plausible Statement: “We’re all broken by sin—it’s why the world is full of pain and why we need God’s forgiveness to be made whole.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity makes sense because everyone’s so messed up, and only our belief in sin explains why the world is such a broken place.”

➘ Existence of an Afterlife

- Assumption: Human souls are immortal, and there is a continued existence after physical death in an afterlife. The afterlife consists of distinct destinations (e.g., heaven and hell) based on one’s relationship with God or moral standing.

- Plausible Statement: “Death isn’t the end; I know my soul will live on, and I trust I’ll be with Jesus in heaven forever.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity has to be true because the hope of heaven gives life meaning, and without an afterlife, everything would feel pointless.”

➘ Final Judgment

- Assumption: There will be a definitive, future judgment by God where all individuals are held accountable for their actions. This judgment restores cosmic justice, rewarding the righteous and punishing the wicked, achieving a transcendent moral equilibrium.

- Plausible Statement: “One day, God will judge everyone fairly, rewarding those who followed Him and setting right every injustice.”

- Misguided Assessment: “The idea of a final judgment proves Christianity’s truth, because only our faith explains how justice will ultimately be served.”

➘ Divine Revelation

- Assumption: God has revealed truth to humanity through sacred texts (primarily the Bible), prophets, or divine experiences. The Bible is divinely inspired and serves as an authoritative guide for faith, morality, and understanding reality.

- Plausible Statement: “The Bible is God’s Word, and it gives me clear guidance on how to live and understand the world.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is obviously true because the Bible answers all of life’s questions perfectly, unlike any other book.”

➘ Purposeful Creation

- Assumption: The universe and human life have a purposeful design, created by God with intention and meaning. Human beings are uniquely significant, often seen as created in God’s image, with a special role in creation.

- Plausible Statement: “God made me for a reason, and my life has meaning because I’m created in His image to do His work.”

- Misguided Assessment: “The universe’s complexity shows Christianity is right, because only our belief in a purposeful design explains why everything fits together so well.”

➘ Spiritual Realm

- Assumption: A spiritual dimension exists beyond the physical world, populated by non-material beings such as angels, demons, and God. This spiritual realm interacts with and influences the physical world, often in unseen ways.

- Plausible Statement: “There’s more to reality than what we see—angels protect us, and demons tempt us, but God is in control.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity must be true because I’ve felt spiritual forces at work, and only our faith explains angels and demons.”

➘ Providence and Divine Plan

- Assumption: God has a sovereign plan for history, guiding events toward a predetermined outcome. Events in the world, including suffering and blessings, are part of God’s purposeful will or permissive allowance.

- Plausible Statement: “Everything happens for a reason; God has a plan for my life, even when things seem chaotic.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is proven by how everything in my life works out, because only our God could orchestrate events so perfectly.”

➘ Human Free Will and Responsibility

- Assumption: Humans possess free will, enabling them to make moral choices, but are accountable to God for those choices. Free will coexists with divine sovereignty, though the precise relationship varies across Christian traditions.

- Plausible Statement: “God gave me the freedom to choose, but I know I’ll answer to Him for how I live my life.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity makes sense because I can choose my actions, and only our faith explains why we’re responsible to God for them.”

➘ Incarnation and Atonement

- Assumption: God became human in the person of Jesus Christ (the Incarnation), who is both fully divine and fully human. Jesus’ death and resurrection provide atonement for human sin, offering salvation and reconciliation with God.

- Plausible Statement: “Jesus is God in human form, and His sacrifice on the cross paid for my sins so I can be with God.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is true because Jesus’ resurrection makes perfect sense as the only way to fix our sins.”

➘ Eternal Destiny Based on Faith or Works

- Assumption: An individual’s eternal destiny (heaven or hell) is determined by their response to God, often through faith in Jesus, adherence to moral standards, or a combination of both (varies by denomination). Salvation is ultimately a divine gift, not solely a human achievement.

- Plausible Statement: “I’m saved by trusting in Jesus, not just by being good, and that faith secures my place in heaven.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity must be right because it offers salvation through faith, which is the only way to ensure we go to heaven.”

➘ Miracles and Supernatural Intervention

- Assumption: God can and does intervene in the natural world through miracles, defying natural laws for divine purposes. Supernatural events (e.g., healings, resurrections) are possible and have occurred historically, particularly in biblical accounts.

- Plausible Statement: “God can do miracles today, just like He did in the Bible—I’ve seen His power change lives.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is proven by miracles, because only our God could cause things that science can’t explain.”

➘ Eschatological Hope

- Assumption: History is linear and will culminate in a divinely ordained end (eschaton), often involving Christ’s return, resurrection of the dead, and renewal of creation. This end-state includes the ultimate triumph of good over evil and the establishment of God’s kingdom.

- Plausible Statement: “I know Jesus is coming back one day to make everything new and defeat evil forever.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is true because the world’s chaos shows we’re nearing the end times, just as our Bible predicts.”

➘ Community and Church

- Assumption: The church is a divinely instituted community with a special role in God’s plan, serving as the body of Christ or a means of grace. Fellowship with other believers is essential for spiritual growth and living out God’s commands.

- Plausible Statement: “Being part of my church helps me grow closer to God and live out my faith with others.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is the true faith because our church community feels so special and united, unlike any other group.”

➘ Sacredness of Human Life

- Assumption: Human life has inherent dignity and value, derived from being created in God’s image. This assumption often informs Christian views on ethics, such as opposition to abortion or euthanasia.

- Plausible Statement: “Every person is precious because they’re made in God’s image, so we must protect all life.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is right because it values human life so highly, which proves we’re made in God’s image.”

➘ Reality of Satan and Spiritual Evil

- Assumption: A malevolent spiritual being (Satan or the devil) exists, opposing God’s will and influencing human affairs. Spiritual warfare between good and evil forces is ongoing, affecting both individuals and the world.

- Plausible Statement: “The devil is real and tries to lead us astray, but God’s power is stronger and protects us.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity explains all the evil in the world because only our faith recognizes Satan’s influence behind it.”

➘ Redemptive Suffering

- Assumption: Suffering has a purpose within God’s plan, often serving as a means of spiritual growth, discipline, or participation in Christ’s suffering. Suffering is not meaningless but is ultimately redeemable in light of God’s justice and love.

- Plausible Statement: “My struggles aren’t pointless—God uses them to make me stronger and closer to Him.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity must be true because my suffering has meaning, and only our faith says God can turn pain into something good.”

➘ Universal Applicability of Christian Truth

- Assumption: Christian teachings about God, morality, and salvation are universally true and applicable to all people, regardless of culture or time. Other worldviews or religions are incomplete or incorrect in light of Christian revelation.

- Plausible Statement: “The truth of Jesus is for everyone, no matter where they’re from—it’s the only way to truly know God.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is clearly the only true religion because its teachings fit every culture’s deepest needs perfectly.”

➘ Hope in Divine Justice

- Assumption: God’s justice ensures that all wrongs will be righted, either in this life or the next, preventing ultimate despair in the face of earthly injustice. This justice is transcendent, surpassing human systems of morality or law.

- Plausible Statement: “Even when the world seems unfair, I trust God will make everything right in His perfect justice.”

- Misguided Assessment: “Christianity is proven by the promise of God’s justice, because only our faith guarantees that every wrong will be fixed.”

Notes

- These assumptions are drawn from mainstream Christian theology, particularly within Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox traditions. Variations exist across denominations (e.g., Calvinist vs. Arminian views on free will or predestination).

- The first plausible statement reflects how a Christian might articulate or imply the assumption in everyday language. The second statement shows a misguided circular reasoning where the assumption is used to “prove” Christianity’s alignment with reality, reinforcing the critique of a “warped” reality.

- The circularity arises when Christians interpret reality through these assumptions and then claim their ideology aligns with reality, as the assumptions themselves shape their perception of what reality is.

- Not every Christian may consciously hold or express all these assumptions, but they are implicit in much of Christian doctrine and practice.

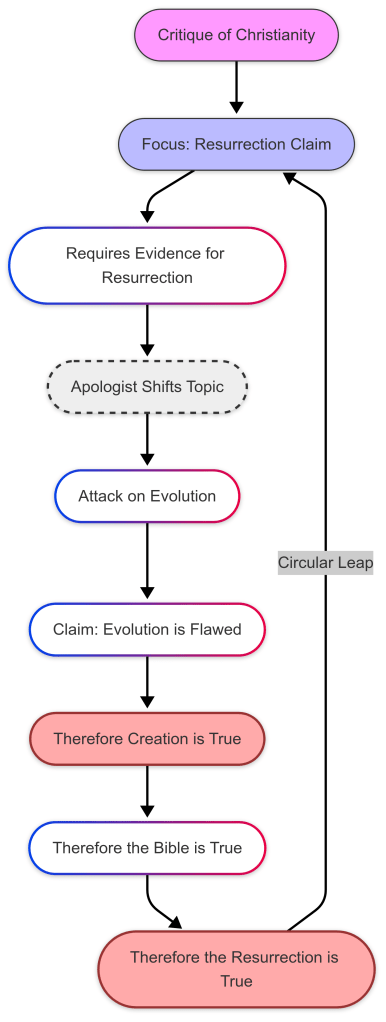

◉ 4. Circularity at the Core

What makes this ideological system particularly resilient is its epistemic circularity. The Christian starts with belief in God, interprets evidence through assumptions drawn from that belief, and then points to that interpretation as confirmation of God.

Circular structure:

- Start with belief (e.g., “God is good and in control”)

- Create interpretive rules (e.g., “Evil must serve a divine purpose”)

- Interpret the world through those rules (e.g., “This tragedy made me stronger”)

- Return to belief as vindicated (“See? God knew what He was doing.”)

This structure ensures that no evidence can truly falsify the belief—because all evidence is interpreted through a lens crafted by the belief itself.

◉ 5. Contrast with Epistemic Integrity

In contrast, a worldview grounded in epistemic humility and Bayesian reasoning adjusts belief proportionally to the evidence. When evidence grows weaker, credence diminishes. When a hypothesis fails to predict the data, it is revised or abandoned.

Christian belief resists this. It insists on unchanging conviction regardless of contrary evidence. The structure of the belief system is rigged to reinterpret anomalies rather than accept disconfirmation. Any threat to the central tenets is anesthetized by doctrine (e.g., “lean not on your own understanding”) or rebranded as spiritual warfare (e.g., “Satan is attacking your faith”).

◉ 6. The Illusion of Coherence

Many Christians claim their worldview is internally coherent. But this coherence is not achieved by explanatory power—it is achieved by insulation. The system defines its own terms, creates its own questions, then supplies the answers. This isn’t real epistemic rigor—it’s an echo chamber.

- Hell exists because God is just.

- God is just because the Bible says so.

- The Bible is trustworthy because it was inspired by God.

- And God… is proven by the need for hell.

This closed-loop coherence looks impressive only from the inside. To an external observer, it’s a carousel spinning in theological air.

◉ 7. Realignment Under Duress

When confronted with challenges—contradictions in scripture, moral atrocities attributed to God, theological confusion—believers often “realign” the narrative, not by changing their beliefs, but by further layering assumptions:

- “That part of the Bible must be metaphorical.”

- “God allowed that because of a greater unseen good.”

- “You’re judging God with human reasoning.”

Each move bleeds the belief deeper into the interpretive process. The ideology becomes not just a set of beliefs, but the very conditions of what the believer is allowed to believe.

◉ Conclusion: Why the Bleeding Never Stops

Christianity functions as a bleeding ideology because the belief is not kept quarantined from the tools of evaluation—it saturates them. It builds the very lens through which it is viewed, then claims clarity of vision. Every assumption drawn from Christian doctrine becomes both premise and conclusion, shaping perception so thoroughly that real testing is impossible.

This is not a searchlight but a spotlight—illuminating only what the believer has already decided must be true.

To the Christian reading this: the issue is not that your beliefs are wrong because they’re Christian. The issue is that you’ve set up a system where they can’t be wrong—because your system is designed to protect them from scrutiny.

That is not faithfulness. It is epistemic fragility wearing the mask of confidence.

And unless the bleeding is stopped—unless belief is kept out of the criteria for belief—the ideology will never be tested. It will only ever be affirmed by itself.

And that is not truth. That is insulation.

Leave a comment