“A theory that explains everything, explains nothing.”

— Karl Popper

“If a theory purports to explain everything, then it is likely not explaining much at all.”

— Massimo Pigliucci

Is there any possible outcome that

would not point to either a sovereign God

or demonic forces within your ideology?

The Illogic of Dual-Agent Theism

Some religious systems try to explain the world by dividing it neatly into two forces. Everything good is explained as the work of God, and everything bad is explained as the work of Satan, demons, or sinful humans. At first glance, this seems like a clear way to make sense of life. It reassures people that nothing is random or meaningless—every joy is a blessing and every tragedy has a hidden purpose.

But this neat division comes at a cost. If every single event, no matter what it is, already has a ready-made explanation, then nothing can actually count as evidence against the belief. A system like this may feel strong, but it is really fragile. Instead of helping us understand reality, it simply labels events after they happen. Philosophers call this explanatory sterility: the system pretends to explain everything, but in truth it explains nothing.

Key Ideas in Simple Terms

To really see the problem, let’s break down some important terms:

Ontic Dualism: The belief that reality is structured around two opposing forces: God and Satan. Every event, whether good or bad, must fall into one of these two categories.

Explanatory Closure: A worldview is “closed” when it already has an explanation for anything that could possibly happen. Closure may sound like completeness, but it actually means the system can never be challenged by new evidence.

Explanatory Sterility: A system is sterile when it cannot be tested by reality. If it explains good weather as a gift from God, and storms as attacks from Satan, then it has explained nothing at all.

Tautological Coverage: A tautology is when something is true by definition rather than by discovery. Saying, “If good, then God; if bad, then Satan,” is a tautology. It restates the outcome instead of giving an explanation.

A Quick Look at Logic

If we write the idea of dual-agent theism in logical form, it looks like this:

This means: for every event , either God caused it, or Satan caused it, or humans caused it. Notice how airtight that looks—no matter what event happens, it must be one of those three. But that’s exactly the problem. The system is unfalsifiable. If a theory cannot possibly be proven wrong, then it cannot really be called an explanation.

A Quick Look at Probability

Bayesian reasoning is a way of updating our beliefs when new evidence appears. A good system leaves room for surprise—it admits that there might be unknown causes we have not thought of. But in dual-agent theism, the probability of “unknown causes” is set to zero:

When that happens, the Bayes factor—which tells us how much evidence should change our belief—stays stuck near :

This means evidence has no impact. No matter what happens, people’s beliefs remain exactly the same. It’s like wearing noise-cancelling headphones in a storm—you don’t hear the thunder, so you never know it’s there.

The Plane Crash Story

To see why this matters, let’s imagine a tragic plane crash. Hundreds of people are on board. The plane goes down, and most passengers die. In the aftermath, families grieve, news reports fill the air, and survivors share their stories. This is the kind of event that really tests whether a belief system can handle evidence.

Now watch how dual-agent theism responds.

One passenger misses the flight because his car breaks down. His friends say it was God’s providence—the accident that made him late was actually protection. Another passenger switches to the doomed flight at the last minute. If she dies, people say it was Satan’s snare or perhaps a punishment from God. If she survives, they say it was part of God’s plan to give her a dramatic testimony.

A child survives because her father shielded her. Believers say this was divine sacrifice, with the father’s death “allowed” by God for a greater purpose. Meanwhile, another parent who loses a child is told her grief is a test of faith meant to strengthen her. An elderly couple dying together is called a “merciful closure.” Newlyweds dying together is explained as God’s mysterious timing.

The stories keep multiplying. A pastor who dies in the crash is called a martyr, his death meant to inspire others. A survivor who later loses faith is explained as falling into Satan’s traps, while a survivor who becomes a missionary is celebrated as proof that God brings good from tragedy. Even the national response—public mourning, calls for unity, moments of silence—is explained as a divine warning to the whole country.

Notice what’s happening. No matter the detail—who dies, who lives, who changes faith, who loses it—every possible outcome has already been absorbed into the framework. Nothing can count against it. This is what philosophers mean by tautological coverage: every result “fits,” so the system explains nothing.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just about religion. The same pattern shows up in conspiracy theories. If evidence supports the theory, it’s proof. If evidence contradicts it, that just means the conspiracy is deeper than anyone thought. Either way, the theory “wins.” But this is an illusion of strength. In reality, such systems are sterile because they never risk being wrong.

Real explanations are different. Science, history, and rational investigation all work because they allow evidence to matter. If a scientific theory predicts rain and the sky stays clear, the theory must be revised. If historians uncover new evidence that contradicts an old story, the story changes. That’s what makes these systems powerful—they can be tested, challenged, and improved.

The Missing Safeguards

Why does dual-agent theism feel convincing to so many? Because it lacks the very safeguards that make real inquiry reliable.

- It leaves no probability for the unknown. Everything is forced into God/Satan/human categories.

- It ignores base rates. Most plane crashes are caused by mechanical failure or human error, but these explanations are brushed aside.

- It suppresses falsifiability. No possible event could count against the belief.

- It multiplies explanations. Every surprise gets rebranded as a mystery, a test, or a greater good.

- It relies on anecdotes—cherry-picking dramatic stories as proof, while dismissing counterexamples.

- It starts with dogmatic priors—beliefs set so high that no evidence could ever bring them down.

These missing safeguards explain why the system feels “safe” to believers, but also why it fails as a real explanation.

Conclusion

Dual-agent theism looks comprehensive because it has an answer for everything. But its very ability to absorb all outcomes is what makes it sterile. By always assigning events to God, Satan, or human sin, it prevents genuine learning. Evidence loses its power, and belief becomes fixed.

The larger lesson is that a good framework must take risks. It must allow evidence to count both for and against it. That is how we grow in knowledge—by letting the world surprise us, by keeping space for the unknown, and by being willing to change our minds when the facts demand it. Systems that refuse to allow this may feel comforting, but they leave us trapped in explanations that explain nothing at all.

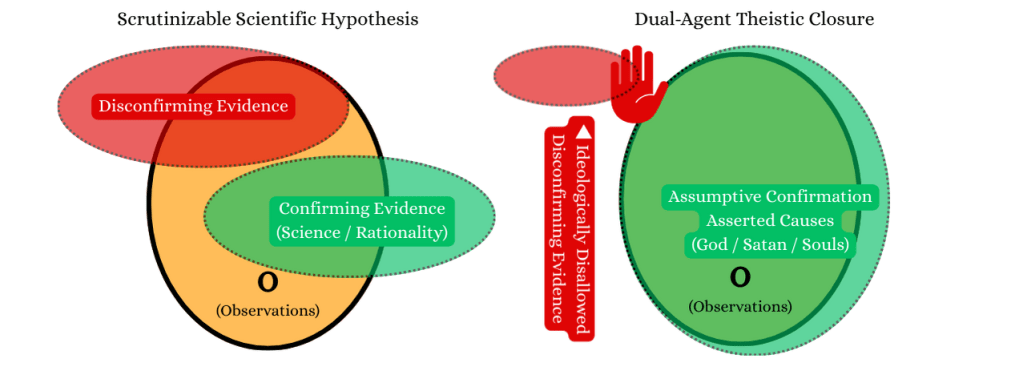

Left Side (Science / Rationality)

✓ We start with observations — what we can see, measure, and test.

✓ From these observations, we can gather both confirming evidence (things that support a theory) and disconfirming evidence (things that go against it).

✓ Science accepts both kinds of evidence. If the evidence supports the theory, good. If it challenges the theory, also good — because it helps us refine or replace bad explanations.

➘ In this system, a theory has to survive possible challenges to remain credible.

Right Side (Ideology / Faith-based Explanations)

✓ Observations are still there, but the “explanation” is already assumed (e.g., “God did it,” “Satan did it,” or “souls exist”).

✓ Any evidence that seems to confirm the assumption is accepted.

✓ But disconfirming evidence is blocked out — it’s not allowed to count against the explanation.

➘ That means the explanation can never be proven wrong, no matter what is observed. It looks strong, but only because it refuses to admit being tested.

The Core Message

When you let all evidence count (science/rationality), your ideas can actually be tested, corrected, and improved.

When you block evidence that doesn’t fit your assumptions (ideology/faith), your system may seem airtight, but it actually explains nothing — because it would look the same no matter what happens.

| Feature | Scientific/Rational Framework | Dual-Agent Theistic Framework |

|---|---|---|

| How events are handled | Some outcomes confirm a hypothesis, others count against it. | Every outcome is fitted into God/Satan/human sin. |

| Falsifiability | A model can be proven wrong if evidence contradicts it. | No possible evidence can ever prove it wrong. |

| Probability space | Leaves room for the unknown: | Forces everything into fixed categories: |

| Bayesian update | Evidence can raise or lower belief: Bayes factors can be much greater or smaller than | Bayes factors stay near |

| Explanatory power | Explains some outcomes better than others; real traction. | Predicts all outcomes equally; becomes sterile. |

| Response to surprise | Surprising results may falsify or revise the model. | Surprises are reinterpreted as “tests,” “mysteries,” or “attacks.” |

| Learning potential | Allows beliefs to change as evidence builds. | Locks beliefs in place; no evidence can alter them. |

A more academic discussion of the concept:

Leave a comment