The Outrage Trap:

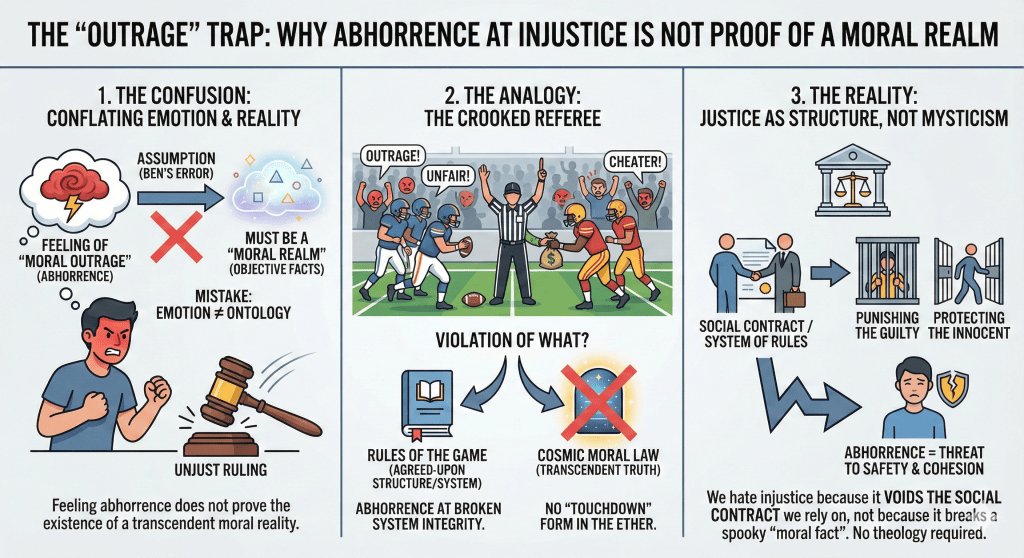

In discussions about ethics and theology, there is a ubiquitous category error that frequently paralyzes rational discourse. It is the assumption that because a violation of justice triggers a profound feeling of moral abhorrence, then justice and morality must be ontologically the same thing.

This error leads many believers and moral realists to conclude that anyone who denies the existence of transcendent, objective moral facts (a moral anti-realist) must therefore be incapable of recognizing or caring about injustice.

A recent comment in a Christian apologetics Facebook group directed at me perfectly illustrated this confusion:

“I only read until I saw ‘Justice is not morality’ and couldn’t stomach any more than that… When people think a judge makes an unjust ruling, do they not respond in a morally outraged manner?”

The commenter notices the reaction (outrage) but completely misidentifies the stimulus.

It is entirely possible—and logically consistent—to find an act grotesque, abhorrent, and profoundly unjust without ever believing there is an actual “moral realm” containing transcendent moral facts. To understand why, we must rigorously distinguish between justice as a structure and morality as an ontology.

1. Defining the Distinction: Structure vs. Ontology

The core of the confusion lies in conflating two very different concepts that happen to share the same emotional vocabulary.

Justice is Structural and Procedural

Justice refers to a system of rules, a social contract, or an agreed-upon procedure for arbitrating disputes and distributing outcomes. It is a human construct designed to facilitate social cohesion.

- Justice is about adherence to the rules of the system. A “just” outcome is one arrived at by following the agreed-upon procedure fairly. An “unjust” outcome occurs when the procedure is subverted—when a judge takes a bribe, when evidence is planted, or when the innocent are punished knowingly.

- Justice is conditional. It depends on the existence of a social framework. Without beings interacting under a set of shared expectations, the concept of “justice” is meaningless.

Moral Realism is Ontological

When apologists or moral platonists speak of “morality,” they are usually referring to something entirely different: a domain of objective truths about right and wrong that exist independently of human minds, invention, or culture.

- Moral facts are claimed to be discovered, not invented. They are often asserted to be grounded in the nature of a deity or the fundamental fabric of reality.

The mistake the commenter made—the “Outrage Trap”—is assuming that because we feel outrage at a structural failure (injustice), that outrage must be evidence of an ontological reality (moral facts).

2. The Mechanism of Outrage: Why Anti-Realists Hate Injustice

If a moral anti-realist doesn’t believe injustice violates a cosmic law, why do they still feel abhorrence when they see it?

The answer lies in evolutionary psychology and game theory, not theology.

Humans are intensely social primates. We cannot survive alone. We rely on cooperation, reciprocation, and group safety. To make group living possible, we inherently develop “social contracts”—implicit agreements that we will follow certain rules in exchange for the benefits of the group.

The primary benefit of the social contract is predictability and safety. We agree to submit to laws on the condition that the system attempts to distinguish the guilty from the innocent.

When we witness a gross injustice—such as an innocent person being knowingly punished—we feel abhorrence not because our “soul” is detecting a disturbance in the moral ether. We feel abhorrence because the fundamental safety mechanism of our social existence has been breached.

If the system punishes the innocent, the contract is void. The rules no longer protect us. That realization is terrifying to a social animal. Our outrage is the evolved emotional alarm bell signaling a threat to social cohesion and personal safety.

3. The Analogy of the Crooked Referee

We can demonstrate that outrage does not require moral realism by looking at lower-stakes systems of rules.

Imagine the final moments of a championship sports match. One team is about to win, but a referee intentionally makes a fraudulent call to hand the victory to the other team because he was bribed.

Every fan watching will experience intense abhorrence. They will scream that it is “unfair,” “wrong,” and a grotesque violation. They will feel what many call “moral outrage.”

But we must ask: Did that referee violate a transcendent Moral Law of the universe? Is there a platonic Form of the “Touchdown” that existed before humans invented football?

Of course not. The referee violated the constitutive rules of the game.

Football is an arbitrary construct. The rules are invented. Yet, when we agree to play by them, they gain normative force within that context. We feel outrage when the referee cheats not because a cosmic fact was broken, but because the agreed-upon structure of fairness that makes the game meaningful was subverted.

When the arbiter of the rules cheats, it destroys the integrity of the system. We value the system, so we abhor the cheating.

Societal justice is simply this same dynamic raised to the highest possible stakes. It is not a football game; it is our lives, freedom, and well-being. The outrage is proportionally greater, but the mechanism is the same: a reaction to the subversion of the rules we rely on.

Conclusion: The Danger of Conflation

Why does this distinction matter?

When we mistake structural failure for moral ontology, we lose the ability to actually fix problems. If you believe an unjust ruling is primarily a “sin” against a divine order, your solution is theological—repentance, prayer, or awaiting divine judgment.

If you recognize an unjust ruling as a structural failure of a human system, your solution is practical—better oversight, judicial reform, stricter evidence standards, and better checks and balances.

You do not need to believe in spooky, transcendent moral facts to hate injustice. You only need to value human flourishing and recognize that fair systems are necessary to achieve it. The anti-realist feels the same outrage as the realist; they just don’t mistake their own adrenaline for the voice of God.

Leave a comment