Why Deductive Proof Invalidates all Inductive “Proofs”

Christian apologetics often functions like this: accumulate a large pile of inductive considerations (historical claims, testimony, personal experience, “transformation,” cultural impact), and treat internal doctrinal tensions as “mysteries” that do not threaten the rationality of belief. My contention is that this strategy only works if the target belief-system is logically coherent.

If there is a valid deductive proof that Christianity (as defined by its core doctrinal claims, under their intended meanings) is logically incoherent, then the usual inductive arguments for Christianity no longer carry the kind of weight apologists think they carry. They may still be relevant to other questions (psychology, sociology, history-of-ideas), but they cannot rationally establish the truth of an incoherent claim-set.

This post is not a presentation of those deductive demonstrations. This post is about the methodological point: why deductive incoherence, if established, shuts down inductive confirmation for that incoherent target.

1) The gatekeeping idea: evidence presupposes possibility

Inductive reasoning is a tool for deciding between live candidates. It compares hypotheses that are at least logically possible and asks which one better accounts for the data. If a hypothesis is not a live candidate—because it collapses into contradiction—then “evidence for it” becomes a category error.

Evidence can do many things:

- It can show that people report an experience.

- It can show that a text exists and was copied early.

- It can show that an event is plausible given background facts.

- It can show that a belief produces certain psychological effects.

But evidence cannot do the one thing apologists want it to do when the target is incoherent: it cannot make an impossible proposition-set become possible.

When the target claim-set is internally inconsistent, no number of contingencies can “add up” to a coherent truth-apt worldview. At most, the contingencies motivate a revision of the claim-set into something coherent. But that is a different target.

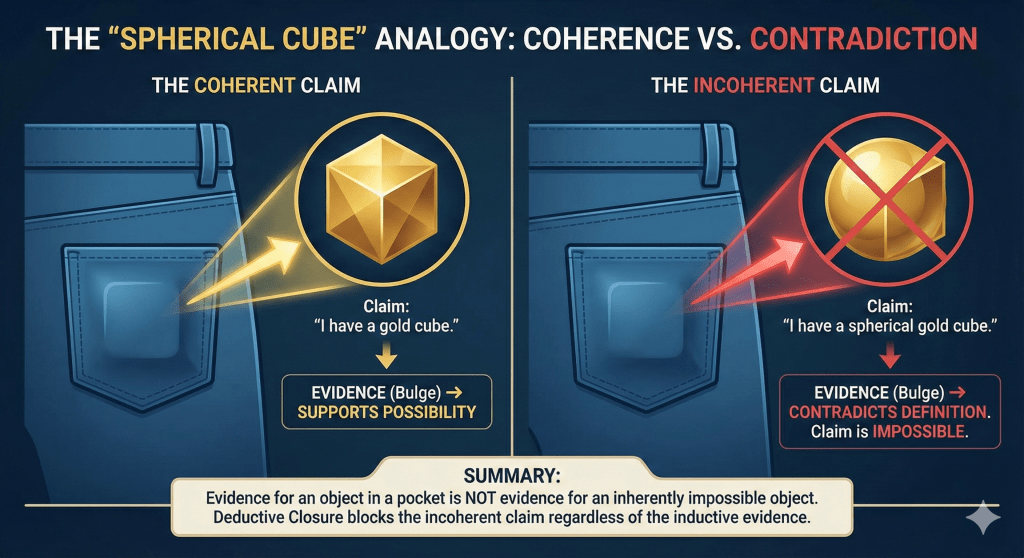

2) One analogy that captures the structure cleanly

Consider these two claims:

- Claim A: I have a key in my pocket.

- Claim B: I have a key made entirely of air in my pocket, and it still produces a bulge.

Now consider evidence:

- My pocket visibly bulges.

- You can feel something key-shaped through the fabric.

That evidence can genuinely support Claim A. It makes Claim A more plausible than it otherwise would have been.

But that same evidence cannot do what it would need to do to support Claim B. The “bulge” can support “there is some object in my pocket.” It can even support “there is a key-shaped object in my pocket.” What it cannot support, under stable meanings, is the incoherent add-on: “made entirely of air” while still producing the physical effect that prompted the evidence in the first place.

So what happens rationally when someone asserts Claim B?

Not this: “Let’s collect more bulge-evidence.”

Instead: the add-on collapses the claim as stated. The pressure is to revise or retract the add-on, or to redefine the words in a way that changes the claim.

That is the pattern I mean to highlight. When a claim-set contains an internal impossibility, evidence that would support a non-impossible nearby claim does not salvage the impossible version. It just pushes you toward changing the claim.

3) Working definitions (kept minimal but sharp)

- Inductive support: observations that would be more expected if a hypothesis were true than if it were false (or than if rival hypotheses were true).

- Deductive defeat: a valid derivation of a contradiction from a proposition-set, given stable meanings and whatever background assumptions the proponent already relies on.

- Deductive closure: once a proposition-set is deductively defeated, inductive support cannot confirm that proposition-set as stated; at most it can motivate reinterpretation, revision, or abandonment.

The key phrase is “as stated.” If you revise the doctrine to avoid the contradiction, you have changed the target of confirmation. That may be a reasonable move, but it concedes the central methodological point: the original target could not be confirmed because it was not a live candidate for truth.

4) The principle in plain form

If a doctrine-set entails a contradiction, then:

- It cannot be true under those meanings.

- Therefore it cannot be confirmed by evidence as that doctrine-set.

This is not anti-Christian special pleading. It’s a general constraint on rational inquiry. If the hypothesis is incoherent, the evidential question “Is it true?” is no longer the right question. The right question becomes: “Which revisions make it coherent?” or “Which coherent alternative best explains the data?”

5) The crucial distinction many debates blur

A common maneuver in apologetic discussion is to slide between two different targets:

- Target 1: Christianity as a specific doctrinal package (Trinity, incarnation, atonement, divine attributes, etc.).

- Target 2: Christianity-lite as a loose spiritual posture (vague theism with Christian branding, elastic enough to dissolve tensions when pressed).

Inductive arguments can sometimes be made to look persuasive only because the target quietly shifts from Target 1 to Target 2 mid-conversation. When the doctrinal package produces contradictions, the apologist “solves” them by loosening meanings, weakening claims, or appealing to mystery—then returns to speaking as though the original robust package has been defended.

Deductive closure blocks that maneuver by forcing the target to remain fixed. If the robust package is incoherent, evidence for “something spiritual happened” cannot be counted as evidence for that incoherent package. At best it is evidence for some revised hypothesis that does not carry the same content.

6) Why “a lot of evidence” does not help

People often respond to coherence critiques with volume:

- “But there’s so much historical evidence.”

- “But millions have experienced transformation.”

- “But look how many witnesses.”

- “But the Bible is uniquely powerful.”

This response assumes that evidential weight behaves like this:

More supportive considerations can eventually outweigh any defeater.

That is how inductive tradeoffs work when you are comparing coherent hypotheses. But a contradiction is not a competing empirical datum. It is a structural failure of the hypothesis itself.

If the hypothesis is internally impossible, adding more evidence does not “outweigh” the impossibility. It simply forces you to interpret the evidence as support for something else—some coherent neighbor of the original view.

The pocket-bulge does not become evidence for an air-key by accumulating more tactile impressions. The impressions only become stronger support for the ordinary claim that there is an object in the pocket.

7) Three common escape routes, and the cost of taking them

- “It’s a mystery, not a contradiction.”

Mystery is an epistemic category: we don’t know how something works. Contradiction is a logical category: the claims cannot all be true together. Mystery can coexist with coherence; contradiction cannot be dissolved by calling it mystery. If you mean “we lack a model but there is no contradiction,” then specify the meanings and show the consistency. If you cannot, mystery is functioning as a label that blocks scrutiny. - “Logic doesn’t bind God.”

This response dissolves argument itself. If logic is optional, then no argument can obligate anyone to accept Christianity either. You cannot coherently demand that critics respect inference while claiming your doctrine is exempt from inference. - “It’s analogical language.”

Analogical language can be legitimate. But it has a price: you must state stable meanings and inference rules. If terms are so elastic that they prevent contradiction whenever needed, then the hypothesis is underdetermined and cannot be strongly confirmed by evidence either. A claim-set that cannot be pinned down cannot be robustly supported.

Each escape route concedes the same thing: the original target is not being defended as a coherent, stable proposition-set. And once that concession is made, the standard inductive case does not reach the conclusion apologists advertise.

8) What this commits the Christian apologist to

If someone wants inductive arguments for Christianity to carry genuine rational force, they must do coherence work up front. Specifically, they must do at least one of these:

- show that the core doctrinal package is logically coherent under stable meanings,

- revise the doctrine into a coherent version and clearly acknowledge the revision,

- or adopt a non-classical logic and defend that choice, while acknowledging what it implies for their own ability to infer anything about God from argument.

Absent that, the common apologetic strategy is upside down: it treats evidence as if it can do the job of coherence. It cannot.

◉ Considerations Articles that Reflect Deductive Proofs Against Christianity.

#08 ✓ Consider: Is the confirmation of the Holy Spirit distinguishable from an evil demon or psychological self-deception?

P1: A method M can confirm hypothesis H only if M is able, at least in principle, to discriminate H from relevant alternatives.

P2: “Inner confirmation by the Holy Spirit” (M) is claimed to be phenomenologically indistinguishable from (i) deception by a malign spirit, and (ii) psychological self-deception.

P3: If M is indistinguishable across H and relevant alternatives, then M does not discriminate H from those alternatives.

Conclusion: Inner confirmation (as described) cannot function as confirmatory warrant for Christianity unless a non-question-begging discriminator is supplied.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: absent a discriminator, “inner confirmation” cannot rationally do the confirming work claimed.

✓ Escape cost

Provide publicly checkable discrimination criteria, or concede that “inner confirmation” is not confirmation but merely a private experience report.

#27 ✓ Consider: Is it possible this profound peace and joy I feel isn’t actually from the Christian God?

P1: If experience E is compatible with H and also compatible with ¬H, then E alone cannot confirm H.

P2: Profound peace/joy (E) is compatible with Christianity (H) and with many non-Christian mechanisms (¬H) such as psychology, community bonding, expectancy effects, and non-Christian spiritual frameworks.

Conclusion: Peace/joy cannot, by itself, confirm Christianity; any confirming force must come from auxiliary premises that uniquely connect E to H.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: if the experience does not discriminate, it cannot confirm.

✓ Escape cost

Specify a unique tie from E to Christianity that does not presuppose Christianity (otherwise the support becomes circular).

#29 ✓ Consider: Wouldn’t the personal introduction of a God take away my free will to reject that God?

P1: Having clearer information about a choice does not remove the capacity to reject that choice.

P2: “Free will to reject” concerns volitional capacity (choosing), not epistemic opacity (lack of information).

P3: People frequently reject authorities they believe are real (clear awareness does not force compliance).

Conclusion: “God cannot clearly reveal himself because it would remove free will to reject” confuses epistemic access with volitional capacity.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: the standard “free will” reply fails on conceptual grounds.

✓ Escape cost

Redefine “free will” as “freedom from epistemic pressure,” which also undermines the freedom-status of ordinary informed choices.

#30 ✓ Consider: Can we legitimately be held culpable for following an unrequested & unavoidable sin nature?

P1: Culpability for an action-pattern requires a control condition (some relevant capacity to govern, resist, or avoid).

P2: A sin nature is described as unrequested and unavoidable (not chosen; present prior to agency).

P3: If a disposition is both unrequested and unavoidable, then the control condition for having that disposition is not met.

Conclusion: Assigning culpability for the inevitable outputs of an unrequested/unavoidable nature collapses the control condition; the set {control-based culpability, unchosen unavoidable nature, culpability for its outputs} is unstable.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: once control is removed, “culpability” is being used in a revised sense.

✓ Escape cost

Deny the control condition (and own a non-control notion of culpability), or deny that the nature is truly unrequested/unavoidable in the relevant sense.

#33 ✓ Consider: Would simple forgiveness without bloodshed logically violate the character of the God of the Bible?

P1: In ordinary usage, forgiveness involves release of a debt/penalty without requiring payment as a condition of release.

P2: In common atonement framings, forgiveness is conditioned on satisfaction/payment (bloodshed as the satisfaction condition).

P3: “Release only if paid” is settlement, not release.

Conclusion: The claim-set “forgiveness requires payment” destabilizes the ordinary meaning of forgiveness; one must either redefine forgiveness or abandon the payment-condition framing.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: “forgiveness” cannot simultaneously mean release and conditional settlement without equivocation.

✓ Escape cost

Explicitly redefine “forgiveness,” or shift away from satisfaction-as-condition language and state a different atonement mechanism.

#34 ✓ Consider: Can punishable culpability for an offense be legitimately reassigned to someone other than the offender?

P1: Punishable culpability for an offense is offender-indexed (it attaches to the offender as offender).

P2: Penal substitution, as commonly described, requires punishment borne by one who is not the offender (or not culpable in the offender-indexed sense).

P3: Offender-indexed culpability cannot be transferred to a non-offender without changing what “culpability” means.

Conclusion: The set {offender-indexed culpability, punishment-for-culpability, penal substitution as transfer} is inconsistent unless “substitution” is not actually punishment-for-culpability.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: if the doctrine requires transfer, culpability is being redefined or the doctrine is being softened.

✓ Escape cost

Deny P1 (and explain what culpability is), or reconstrue substitution as something other than transfer of punishment-for-culpability.

#35 ✓ Consider: What is the reasoning behind equating Jesus’ three-day death with the eternal punishment of billions of sinners?

P1: If atonement is penalty-substitution, then the substitute must bear the relevant penalty-type the offenders would bear.

P2: The offenders’ penalty-type is eternal punishment (unending in duration).

P3: Jesus’ suffering/death is temporally finite (bounded).

P4: A finite penalty is not the same penalty-type as an eternal penalty in the respect of duration.

Conclusion: The set {penalty-substitution, eternal penalty-type, finite substitution} cannot all be true together under stable meanings of “penalty,” “substitution,” and “eternal.”

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: the substitution claim either changes meaning or fails.

✓ Escape cost

Deny eternalism about the penalty, deny penal substitution, or redefine “equivalence” so it no longer tracks penalty-type.

#36 ✓ Consider: How does a single offense incur the penalty of eternal punishment as the Bible seems to suggest?

P1: A non-arbitrary penalty scheme requires a proportionality constraint (penalty magnitude tracks offense magnitude in some stable way).

P2: A single human offense is finite in scope (finite agent, finite act, finite duration).

P3: Eternal punishment is unbounded in duration (infinite penalty magnitude in that respect).

P4: A finite offense cannot, under proportionality, warrant an infinite penalty magnitude in the same respect.

Conclusion: The set {proportionality, finite offense, eternal punishment} is unstable; at least one must be revised.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: you either abandon proportionality or abandon eternality (or redefine “infinite offense”).

✓ Escape cost

Reject proportionality (owning arbitrariness), deny eternality, or argue the offense is “infinite” in a coherent, non-handwavy sense.

#37 ✓ Consider: What will prevent tears in Heaven if those in Heaven remain aware that those they love are screaming in Hell?

P1: Heaven includes the absence of sorrow/tears (or complete resolution of such states).

P2: People in heaven retain meaningful personal continuity, including memory and love for others.

P3: People in heaven are aware that some of those they love are in irreversible, ongoing torment.

P4: If P2 and P3, sorrow is a rational/natural response for beings with that continuity.

Conclusion: {P1, P2, P3} cannot all be maintained without significant alteration of memory, love, awareness, or continuity.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: to preserve “no tears,” something central to personhood must be revised.

✓ Escape cost

Accept memory loss, love alteration, ignorance, or a heavily revised psychology of heaven—and then clarify what “personal continuity” still amounts to.

#38 ✓ Consider: If we demonstrate the incoherency of a competing ideology, won’t that make Christianity more probable?

P1: “Not-A is incoherent” does not entail “B is coherent.”

P2: Inductive comparison presupposes that the remaining candidate (B) is a live (coherent) candidate.

P3: Christianity must clear coherence independently of competitor failure.

Conclusion: Refuting competitors does not, by itself, raise Christianity’s probability unless Christianity is independently coherent and the option-space is appropriately partitioned.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: competitor defeat is not confirmatory unless coherence and exhaustiveness are established.

✓ Escape cost

Provide an exhaustive partition of live options and demonstrate Christianity’s coherence; otherwise “competitor defeat” is not confirmatory.

#45 ✓ Consider: Are apparent incoherencies in the Bible simply due to the inscrutability of the Christian God?

P1: If “inscrutability” is used as a general defeater for apparent contradictions, it also undermines confident positive doctrinal claims derived via the same terms and sources (the defeater is symmetric).

P2: Christianity typically requires confident positive claims (not merely “something inscrutable exists”).

P3: A symmetric defeater that blocks contradiction-resolution also blocks determinate doctrine-assertion.

Conclusion: A broad inscrutability move tends to be self-undermining: it saves the view from critique at the cost of dissolving its doctrinal determinacy.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: “inscrutability” cannot be a one-way shield.

✓ Escape cost

Narrowly define when inscrutability may be invoked (with a principled boundary), or accept a much thinner, less determinate Christianity.

#51 ✓ Consider: If a human can sin but not a God, can Jesus truly be fully human and fully God?

P1: “Fully human” implies possession of the essential features of being human (including a genuinely human will and the relevant capacities of human agency).

P2: “Fully God” implies the divine property “cannot sin.”

P3: “Can sin” (as a capacity) and “cannot sin” (as a capacity-denial) cannot both be true of the same subject in the same respect at the same time under stable meanings.

P4: The orthodox claim-set predicates both “fully human” and “fully God” of Jesus.

Conclusion: The package {fully human, fully God, God cannot sin, humans can sin (as capacity)} is unstable unless key terms are partitioned or redefined in a way that avoids contradiction without emptying the claims.

✓ Closure claim

Deductive closure applies: the doctrine requires a non-equivocal “two natures” account, not a mystery label.

✓ Escape cost

Provide a non-contradictory account of “two natures” that specifies (i) what is predicated of whom, (ii) in what respect, and (iii) why this is not merely equivocation on “can/cannot,” “fully,” or “nature.”

Leave a comment