◉ Intelligibility, Minds, and the Leap to God: A Logic Audit

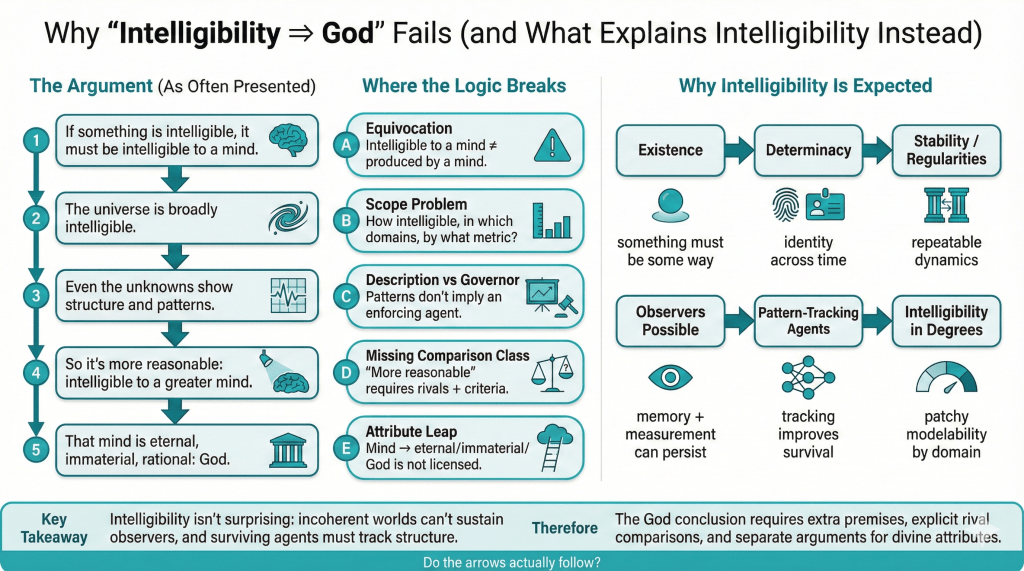

The argument below shows up constantly in Christian apologetics, often framed as if it were a modest observation about how “reasonable” the world is. But the moment you slow it down and make its steps explicit, its incoherence becomes obvious: it equivocates on what intelligible means, slides from “understandable to minds” into “authored by a mind,” and then performs a final, unjustified jump from “perhaps a greater mind” to the full divine-attribute package and the label God. In other words, it is not an argument that carefully earns its conclusion; it is a sequence of rhetorical handoffs that feels intuitive only because its missing premises are kept offstage.

◉ The Formalization of the argument:

The argument feels smooth because each step sounds modest. But the logical load is not where it appears. Most of the work is being done by ambiguity, hidden bridge premises, and an under-argued jump from “intelligible” to “authored by a mind.” Let’s take a look.

Symbol key

✓ = the universe

✓ =

is a mind

✓ =

is intelligible (left intentionally generic at first)

✓ =

is intelligible to mind

✓ =

exhibits stable structure

✓ =

exhibits regularities or patterns

✓ =

is produced by

✓ = agent

governs

(prescriptive sense, not merely descriptive)

✓ ,

,

= divine-attribute predicates

✓ =

is God (in the robust classical-theist sense)

✓ = the evidence being cited (intelligibility, structure, regularity)

Step 1: The formalization, and why it is too weak to support later steps

Premise 1 is usually interpreted as something like this:

✓

Annotation: For any thing , if

is intelligible, then there exists some mind

such that

is intelligible to

.

As written, this is either:

✓ nearly definitional, if “intelligible” simply means “intelligible to some mind,” or

✓ a modest claim about the relation between minds and models, not about the origin of the world.

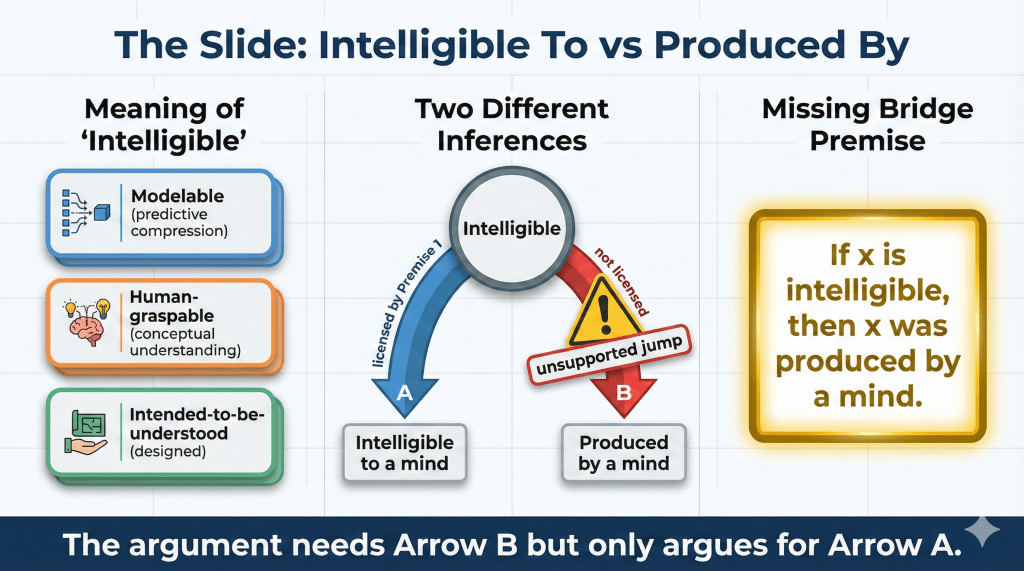

But notice what the argument needs later. It needs intelligibility to imply a producer. That would require something like this stronger bridge:

✓

Annotation: If something is intelligible, then it was produced by a mind.

The original Step 1 does not say that. And without an additional premise, there is no valid path from “intelligible to a mind” to “made by a mind.”

So the first core flaw is a quiet substitution:

✓ from (a comprehensibility relation)

✓ to (a causal origin claim)

Those are not the same kind of claim.

Step 2: The universe is intelligible, but that needs a scope and a metric

Premise 2 is usually stated as:

✓

Annotation: The universe is intelligible.

But “intelligible” can mean very different things, and the argument benefits from leaving it unspecified. Here are three distinct candidates that often get blended:

✓ Intelligible as compressible prediction: the world contains stable patterns that admit compact models

✓ Intelligible as human-graspable: humans can understand the world at a deep explanatory level

✓ Intelligible as intended-to-be-understood: the world is meant to be comprehended

Only the third naturally invites “a mind behind it,” but the evidence most clearly supports the first, and supports the second only unevenly.

If we try to make Step 2 more precise, it might actually look like this weaker and more defensible statement:

✓

Annotation: There exists at least one domain in which the universe is highly modelable.

Or even this mixed statement:

✓

Annotation: Some domains are highly modelable, and some are not (or are not yet).

That matters, because the later leap to God tends to assume something close to a universal:

✓

Annotation: Every domain is highly modelable.

You can still try to defend a universal, but you must argue for it. You cannot smuggle it in by calling the universe “broadly and consistently intelligible” and moving on.

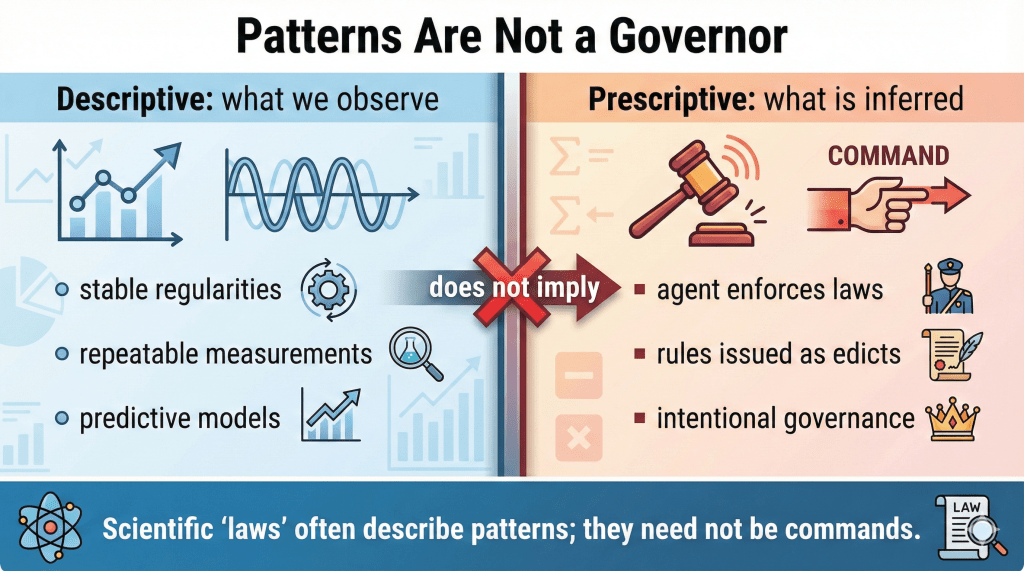

Step 3: Patterns do not entail a governor

Premise 3 contains two different ideas, and they need to be disentangled:

✓ There are patterns and structure

✓ Those patterns are governed

The first can be formalized as:

✓

Annotation: The universe exhibits stable structure and regularities.

But “governed” suggests agency or prescriptive enforcement, which would be closer to:

✓

Annotation: There exists some agent that governs the universe

.

The crucial point is that the entailment is not valid:

✓

Annotation: Regularities do not logically imply a governing agent.

If “laws” are descriptive summaries of stable patterns, then you get “lawlike behavior” without any lawgiver. If “laws” are prescriptive edicts, then you must separately argue why the world should be interpreted prescriptively rather than descriptively.

The argument often gains persuasive force by quietly using “governed” in the prescriptive sense while only having evidence for “patterned” in the descriptive sense.

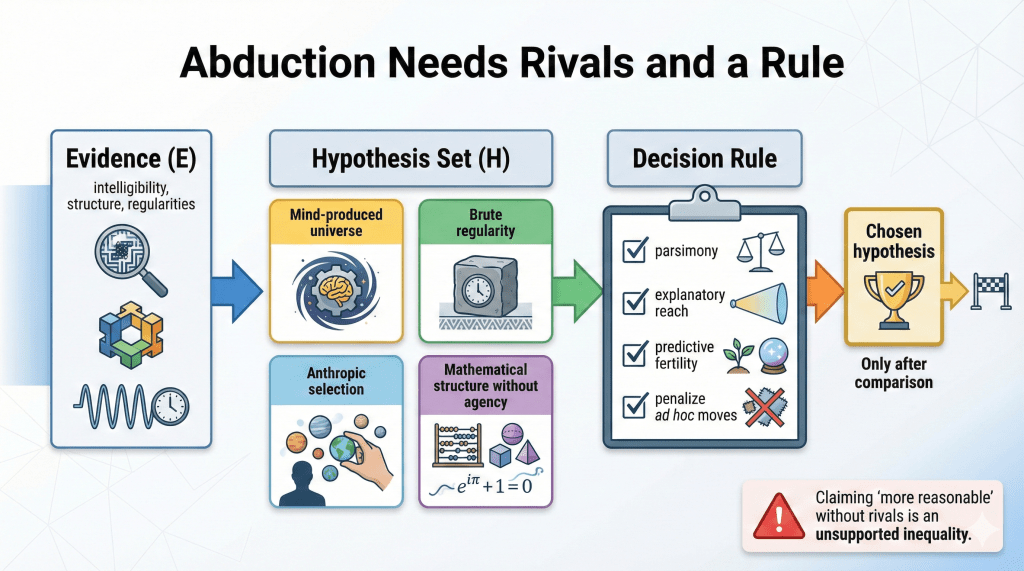

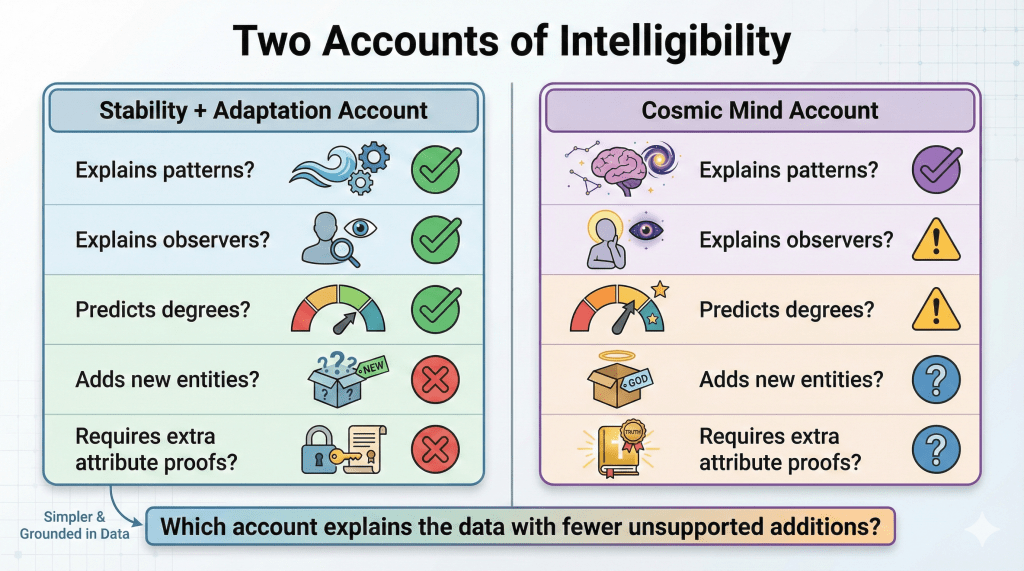

Step 4: “More reasonable” is an abductive claim, but the comparison is missing

Step 4 is where the rhetoric becomes explicitly probabilistic without doing the work of probability. It says “more reasonable,” which is an inference-to-best-explanation move.

To justify that move, you need:

✓ a set of candidate hypotheses

✓ a clear account of what the evidence is

✓ a criterion for “more reasonable”

In symbolic form, a minimal abductive structure looks like this:

✓

Annotation: Define a hypothesis set containing multiple candidate explanations.

Then “more reasonable” needs to cash out as something like:

✓

Annotation: The mind-hypothesis is more probable given evidence

than relevant competing hypotheses

.

Or as a scoring relation if you prefer non-probabilistic criteria:

✓

Annotation: The mind-hypothesis scores better on explanatory virtues relative to evidence than rivals.

But the original argument does not specify:

✓ what the rival hypotheses are

✓ how complex each is

✓ what counts as explanatory success

✓ how we measure “intelligibility” in the first place

Without that, Step 4 is an asserted inequality with no model comparison behind it.

Also, there is a structural asymmetry that often goes unacknowledged: adding a cosmic mind is not a free move. It introduces an additional entity with properties that themselves demand explanation. In probabilistic terms, that typically comes with a prior cost unless independently motivated.

➘ NOTE: Abductive reasoning has narrow pragmatic usage: Abduction as Premature Induction.

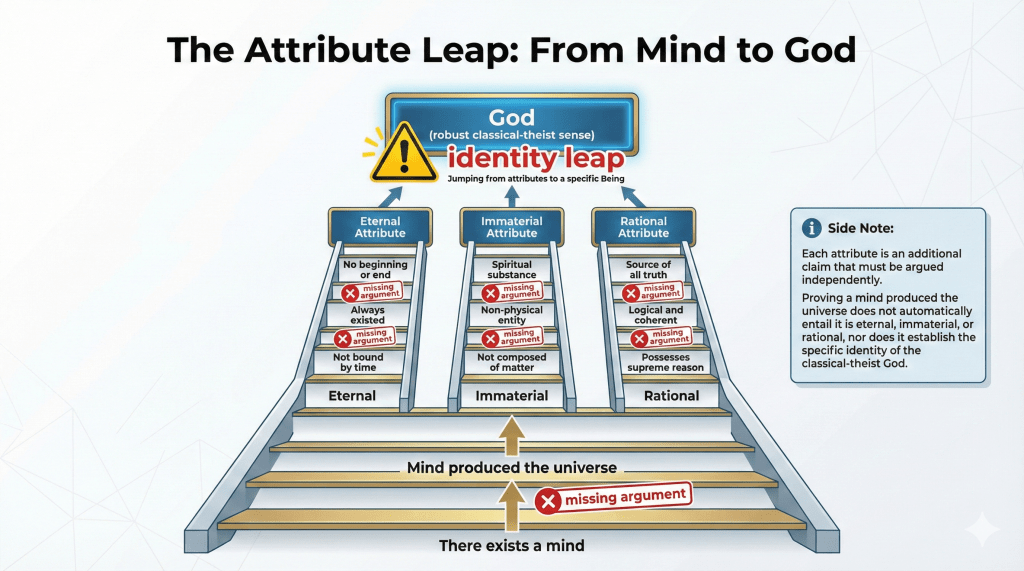

Step 5: Even granting a “greater mind,” the divine package does not follow

Suppose we grant Step 4 for the sake of argument. We might arrive at something like:

✓

Annotation: There exists a mind to which the universe

is intelligible.

Or even:

✓

Annotation: There exists a mind that produced the universe

.

Even that stronger conclusion does not justify Step 5. The Step 5 bundle is:

✓

Annotation: There exists a mind with the standard divine attributes, and

is God.

But the strengthening is invalid:

✓

Annotation: From “a mind exists” you cannot infer the package of divine attributes.

Each attribute requires its own argument.

✓ Eternal: why cannot be finite in time or contingent?

✓ Immaterial: why cannot be physical or implemented in something physical?

✓ Rational: what precise property is meant, and why must the source have it?

✓ God: even if you had the attributes, why identify this with God in the thick theistic sense rather than some other category?

In short: Step 5 is not a conclusion from Step 4. It is a relabeling plus a bundle of additional theses.

The deeper issue: a hidden mind-first metaphysical rule

The argument quietly leans on something like this principle:

✓

Annotation: For any , if

has structure, then some mind grounds that structure.

That is a substantive metaphysical commitment. It is not delivered by the mere observation of structure. If the argument does not defend this principle, it risks circularity: structure implies mind because mind is assumed to be the only acceptable ground of structure.

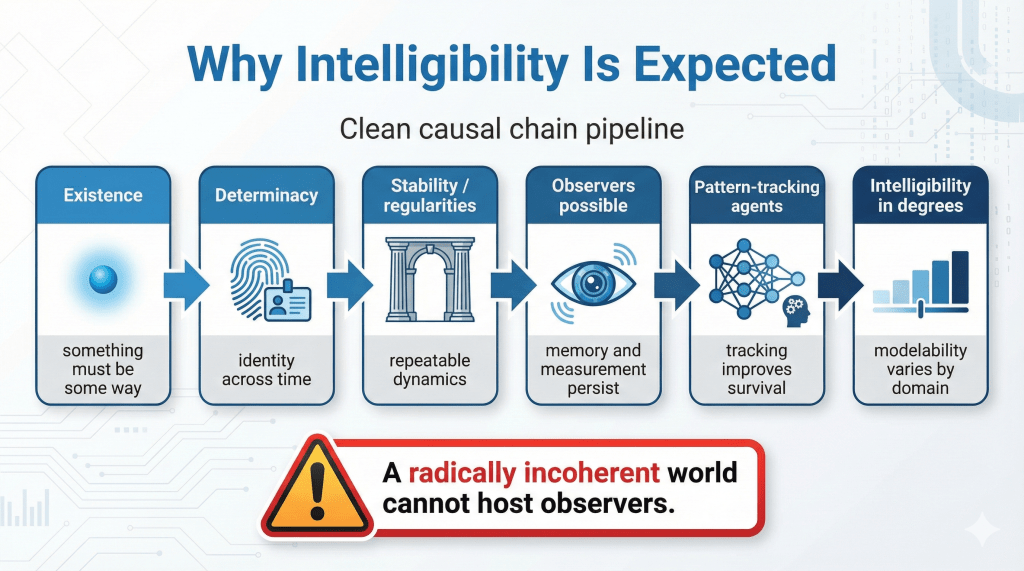

◉ A natural alternative: intelligibility is expected given existence, stability, and survival

Now add the additional argument you requested: intelligibility is not surprising because anything that exists must have an organized substrate, and any entity that arises within that substrate and survives will, by necessity, track regularities to some degree.

This can be stated in three layers: metaphysical constraint, stability constraint, and survival constraint.

1) Metaphysical constraint: existence implies determinate structure

If anything exists at all, it must have some determinate character, otherwise there is nothing to distinguish it from nothing. In symbolic terms:

✓

Annotation: If exists, then

has determinate properties.

Applied to the universe:

✓

Annotation: If the universe exists, it has determinate structure.

And determinate structure yields describable regularities, at least locally:

✓

Annotation: Determinacy entails some stable patterns, because stable identity across time is already a kind of regularity.

This is not yet “laws of physics,” and it certainly is not “a mind.” It is simply the point that existence without any stable constraint is not a coherent target for explanation.

2) Stability constraint: an incoherent world does not sustain entities, processes, or observers

If the world were radically incoherent in the sense of having no stable regularities, persistence becomes impossible. In a world where patterns do not hold even locally, you cannot get stable atoms, stable chemistry, stable memory, stable inference, stable organisms, or stable measurement.

A simple way to represent this is:

✓

Annotation: If the universe lacks stable regularities, then no observers exist.

This is not a rhetorical flourish. It is a constraint. Observers are physically embodied systems that require repeatable dynamics to form, continue, and update internal states.

So the very fact that we are here already tells you something strong:

✓

Annotation: If any observers exist, then the universe exhibits regularities at least sufficient for stable processes.

This flips the intuitive direction many people assume. The question is not “Why is there intelligibility?” as if intelligibility is an optional bonus. The deeper question is “Could there be observers in a world lacking stability?” and the answer is effectively no.

3) Survival constraint: entities that process the world will track patterns, hence find degrees of intelligibility

Now add the evolutionary and functional point. Any entity that survives by processing its environment must, by necessity, exploit stable patterns. Otherwise it cannot anticipate, avoid, acquire, or regulate.

We can express a minimal version like this:

✓

Annotation: If is an agent that survives, then

tracks patterns in the universe

in some way.

Tracking patterns is exactly what yields intelligibility, in degrees:

✓

Annotation: If tracks the universe, then the universe is intelligible to

to the degree that tracking is accurate.

Combine the stability constraint with the survival constraint and you get a powerful expectation:

✓

Annotation: If any observers exist, then at least one observer will find the universe intelligible to some degree.

This is the key inversion: intelligibility is not a surprising feature that cries out for a cosmic mind. It is what you should expect in any world that can host stable, adapting systems.

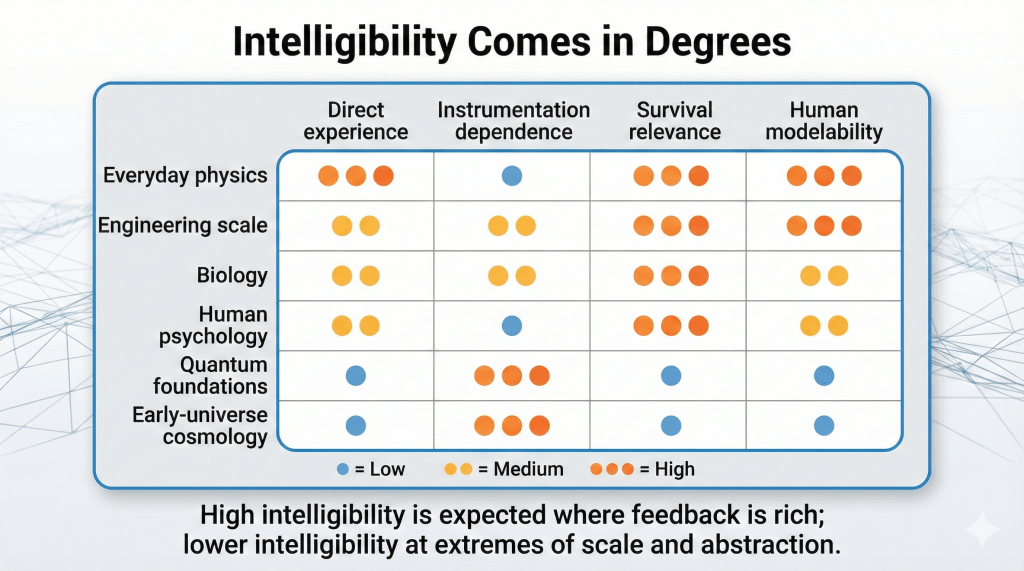

Why “degrees” of intelligibility matters

Humans often notice a mismatch: we can model many things well, but other things remain opaque, probabilistic, or conceptually strained. That mixture is exactly what you would expect under the survival story.

The survival story predicts:

✓ high intelligibility where it matters for survival and mid-scale engineering

✓ lower intelligibility at extremes of scale and energy where direct experience is absent

✓ patchy intelligibility where cognitive architecture is mismatched to the domain

You can represent that informally by indexing intelligibility to domain:

✓

Annotation: The universe is intelligible to agent

in domain

.

Then the expected pattern is not uniform:

✓

Annotation: Some domains are highly intelligible to us, and some are not.

That looks like our actual epistemic situation.

Putting it together: what the original argument can and cannot establish

What the argument can reasonably establish, if you clean it up, is something like:

✓

Annotation: The universe exhibits structure and regularities.

✓

Annotation: There exist observers to whom the universe is intelligible in meaningful ways.

But what it does not establish without additional premises is:

✓

Annotation: There exists a mind that produced the universe.

And it certainly does not establish the divine-attribute bundle:

✓

Annotation: There exists a God-like being with standard attributes.

To reach those, the argument needs explicit bridge premises and a defensible abductive comparison against serious rivals. As currently stated, it mostly trades on the psychological ease of moving from “patterns exist” to “someone is behind the patterns,” while skipping the logical scaffolding that would make that move legitimate.

Closing synthesis

If you start from the constraints of existence and stability, the universe having patterns is not an optional flourish. A radically patternless universe is not a viable stage for durable entities, memory, inference, or observers. Then, given survival and processing, any agent that persists will be tuned to whatever regularities are exploitable, and will experience the world as intelligible in degrees.

So the core observation that the world is intelligible is fully compatible with a purely natural story: stable substrate first, adaptive pattern-tracking later. The original syllogism only becomes a theistic argument if it adds extra premises that explicitly connect intelligibility to intentional authorship and then independently justify the divine attribute package. Without those additions, the leap to God is not a conclusion. It is an insertion.

Leave a comment