Labels Aren’t Arguments: Why “Atheist,” “Agnostic,” “Religious,” “Liberal,” “Conservative,” and Even “Christian” Often Hide More Than They Reveal

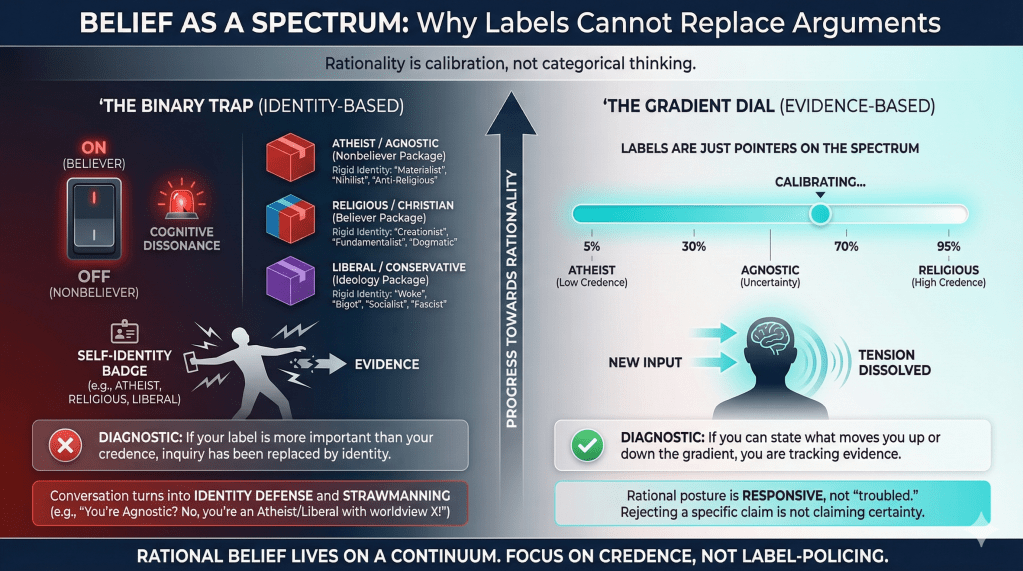

A strange habit has developed in public discourse—especially in apologetics spaces, political spaces, and online debates generally: people treat labels as if they were arguments. They hear a tag—“atheist,” “agnostic,” “religious,” “liberal,” “conservative,” “Christian”—and they immediately behave as though they now understand the person standing in front of them.

They don’t.

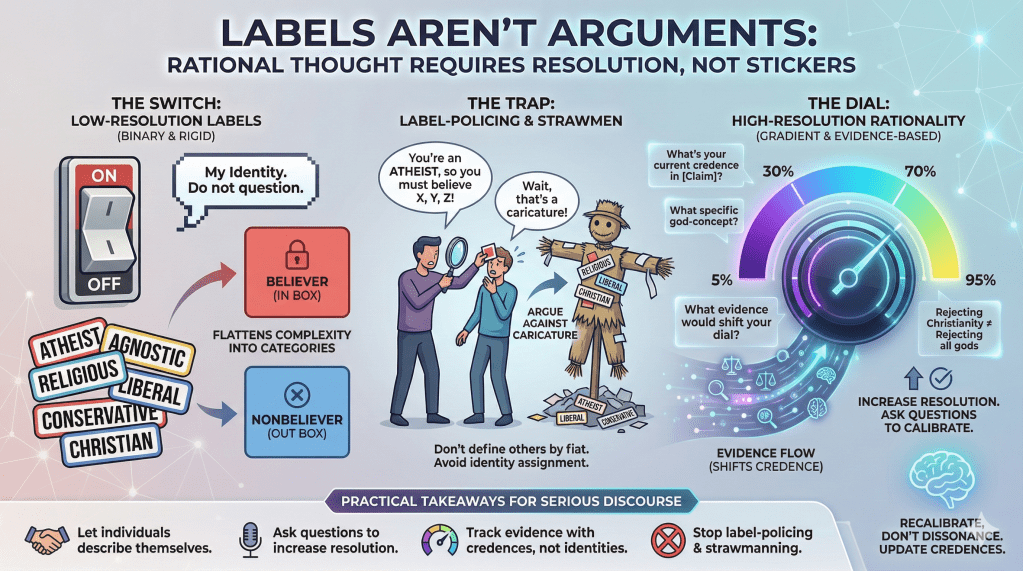

Most of these tags are low-resolution summaries. They compress a complex mental landscape into a sticker. That compression might be useful for quick social navigation, but it is a poor tool for any conversation that aims at clarity.

If you want to talk rationally, stop starting with labels. Start with credences.

Rational belief is gradient because evidence is gradient

Evidence is almost never binary. It rarely arrives as “conclusive” or “nonexistent.” It usually arrives as:

- some considerations that seem to support a claim,

- some considerations that seem to undermine it,

- and a pile of uncertainties about what we’re missing.

A rational mind responds to that reality by adopting a degree of belief that tracks the degree of relevant evidence. That is what it means to be epistemically calibrated: your confidence rises and falls in proportion to the support.

So belief is a dial, not a switch.

A switch says:

- “I’m in.”

- “I’m out.”

- “I’m one of those.”

- “I’m not one of those.”

A dial says:

- “Given what I’ve seen, I’m at 20% confidence.”

- “After hearing that counterargument, I’m at 10%.”

- “If you could show X, I’d move to 40%.”

- “If Y turns out to be false, I’d drop to 5%.”

This matters because many belief-based labels pretend the mind is a switch. They suggest that the rational posture is to pick a camp and then hold that identity like a passport.

But rationality isn’t camp selection. Rationality is calibration.

Why belief-based labels must be gradient if they’re to be honest

If rational belief is gradient, then any label that tries to represent a belief-state should also be understood as gradient—at most, a crude coordinate on an evidential slope.

That immediately changes the tone of the label wars.

The question is not “What are you?” as though that settles the matter.

The question is:

- “What do you currently think is most likely, and how strongly do you hold it?”

- “What would change your mind, and in what direction?”

A label might roughly correlate with those answers, but it will never substitute for them.

Why “disconcerted” and “troubled” often signal identity attachment, not rationality

You sometimes hear people say they felt “disconcerted” or “troubled” by an argument, as if that emotional disturbance is evidence of intellectual seriousness.

Sometimes it is. Often it isn’t.

Those feelings frequently arise when two forces are pulling against each other:

- the pressure to preserve a self-concept or tribal identity, and

- the recognition that new information disrupts that identity.

That’s cognitive dissonance: mental tension generated by trying to hold incompatible things in place.

But a mind that is actually operating on credence calibration doesn’t need to carry that tension for long. It can do something far simpler:

- incorporate the new consideration,

- update its degree of belief,

- and release the strain.

If an argument “troubles” you for weeks or months, that often indicates you’re not merely tracking evidence. You’re defending an identity that the evidence is challenging. The mind becomes a courtroom where the verdict is predetermined, and every new piece of evidence becomes a threat instead of information.

A calibrated mind can register, update, and move on.

Why these common labels convey shockingly little semantic information

Now let’s talk about the actual tags people fling at each other.

“Atheist”

This can mean:

- “I assign very low credence to any gods.”

- “I’m unconvinced by the god-claims I’ve encountered.”

- “I’m not religious.”

- “I reject Christianity.”

- “I identify with secular culture.”

Those are not the same thing. In many conversations, “atheist” functions as shorthand for one narrow claim—not believing in gods. But apologists often treat it as a complete metaphysical package.

That’s why you see the predictable strawmen:

- “So you believe the universe came from nothing.”

- “So you believe life came from rocks.”

- “So you believe everything is random.”

This is not analysis. It’s caricature.

“Agnostic”

This can mean:

- “I’m uncertain about god(s).”

- “The evidence doesn’t currently justify confidence either way.”

- “The concept of ‘god’ is too vague to evaluate cleanly.”

- “I don’t claim certainty.”

- “I’m not interested in the debate.”

And here’s the key: someone can be agnostic in the broad sense while being highly confident that specific god-concepts are false.

If a deity is described with logically impossible traits, dismissing that deity is not an act of dogmatism. It’s an act of coherence-checking.

Rejecting Christianity’s particular god-claims does not entail certainty that no gods exist. That inference is lazy.

“Religious”

This can mean:

- doctrinal commitment,

- ritual practice without literal belief,

- cultural affiliation,

- family tradition,

- aesthetic preference,

- community belonging,

- fear,

- hope,

- existential comfort,

- political identity.

It’s an umbrella term so broad it’s often useless without follow-up questions.

“Liberal” and “Conservative”

These can mean:

- economic policy preferences,

- social policy preferences,

- attitudes toward tradition,

- risk tolerance,

- temperament,

- loyalty to a party,

- regional cultural norms.

In one country “liberal” means one cluster of ideas; in another it means almost the opposite. Even within one country, the meaning changes by decade and subculture.

Treating these labels as if they are stable, precise descriptors is like treating a weather forecast from 1973 as if it applies to today.

Even “Christian” conveys surprisingly little today

In modern discourse, “Christian” can mean:

- Nicene orthodoxy,

- “I go to church and believe in Jesus,” without doctrinal clarity,

- progressive Christianity that rejects classic doctrines,

- charismatic experience-centered spirituality,

- cultural Christianity as ethnic or political identity,

- “I think Jesus is admirable” with minimal theology,

- “I’m not Muslim,” in certain cultural contexts.

That’s why you now see two Christians describe each other as “not really Christian.” The label no longer has the resolution needed to tell you what is actually believed.

If “Christian” can include mutually incompatible theologies, then “Christian” by itself is not a belief-description. It’s a membership signal.

The two basic rules for rational discourse

Here are the two rules that dissolve most label-chaos immediately.

1) Let individuals describe themselves

You have no business telling someone what they “really” are.

You can challenge claims. You can critique reasoning. You can argue against propositions. But identity assignment is not your jurisdiction.

When someone says, “I’m an atheist,” you don’t get to reply, “No, you’re actually X.”

When someone says, “I’m an agnostic,” you don’t get to reply, “No, you’re actually an atheist because you criticize Christianity.”

That is not intellectual engagement. It is social control.

2) Ask the questions that raise resolution to what the context requires

If the label is too fuzzy for the conversation, don’t fight about the label. Increase the resolution.

Instead of arguing about whether someone is “really” atheist or agnostic, ask:

- “What is your current credence that any god exists?”

- “Which god-concept are we evaluating—deistic, personal, interventionist?”

- “What evidence do you think supports it?”

- “What evidence do you think undermines it?”

- “What would you accept as a strong defeater?”

- “What would you accept as strong support?”

- “Which claims are you confident are false, and which are you merely unconvinced by?”

These questions move the discussion from identity signaling to substance.

Why apologists love labels (and why you shouldn’t)

Labels are rhetorically powerful because they let you argue cheaply.

If you can collapse a person into a category, you can preload a script:

- “Atheists believe X, so they’re irrational.”

- “Liberals believe Y, so they’re corrupt.”

- “Conservatives believe Z, so they’re hateful.”

- “Agnostics are just atheists who won’t admit it.”

Once you’ve done that, you don’t have to listen. You don’t have to ask questions. You don’t have to engage the person’s actual reasoning. You simply attack the stereotype.

That’s why label arguments are attractive: they replace difficult inquiry with easy theater.

A higher-resolution alternative: treat people as credence profiles

If you want to be serious, treat people as credence profiles rather than category-members.

A credence profile includes things like:

- degrees of confidence on key propositions,

- what evidence they regard as relevant,

- what evidence would change their mind,

- how they handle uncertainty,

- whether they update when challenged.

That’s the real substrate of rationality. Not labels.

Closing thought

Labels can be useful shorthand in casual contexts. But when labels become the center of the discussion—when people start fighting about who counts as what—the conversation has already moved away from evidence and toward identity.

If you want rational discourse:

- stop treating labels as arguments,

- stop telling others what they “really” are,

- and start asking the questions that increase resolution to the level the discussion actually requires.

Belief is a gradient because evidence is a gradient. Anything that denies that—whether it’s apologetics, politics, or online tribalism—isn’t doing inquiry. It’s doing identity defense.

Leave a comment