The Epistemological Razor:

Cutting Through the Theological Assumption Stack

In the realm of philosophy of religion, debates often center on grand metaphysical claims: the nature of being, objective morality, or the fine-tuning of the cosmos. These discussions can feel profound, wrestling with the very architecture of reality.

However, there is a quieter, sharper instrument in the philosopher’s toolkit that often slices through these Gordian knots before they can even be tied. It is an epistemological principle known as parsimony, most famously popularized as Occam’s Razor.

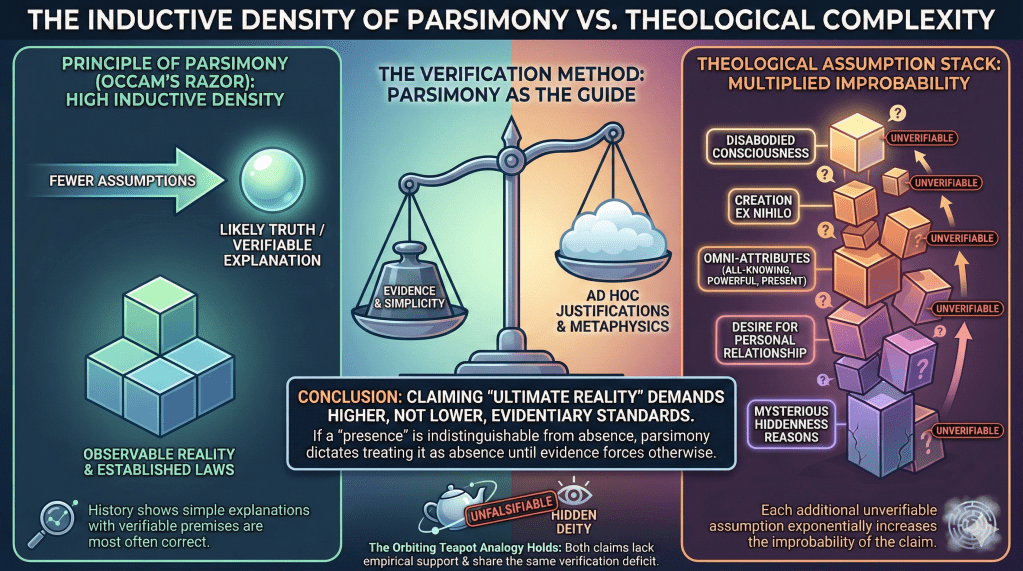

Often misunderstood as a mere preference for “simpler” explanations, parsimony is actually a rigorous standard for evaluating competing hypotheses. When applied unflinchingly to the claims of classical Christian theism, it reveals a startling fragility in the foundation of faith. It suggests that what many believers view as profound theological depth is, in epistemological terms, a precarious tower of unearned assumptions.

This essay will examine the inductive density of parsimony and apply it rigorously to the “stack” of assumptions required to maintain a Christian worldview in the 21st century.

1. Understanding Inductive Density: Why Simplicity Matters

Before applying the razor, we must sharpen it. What exactly is parsimony, and why should we care?

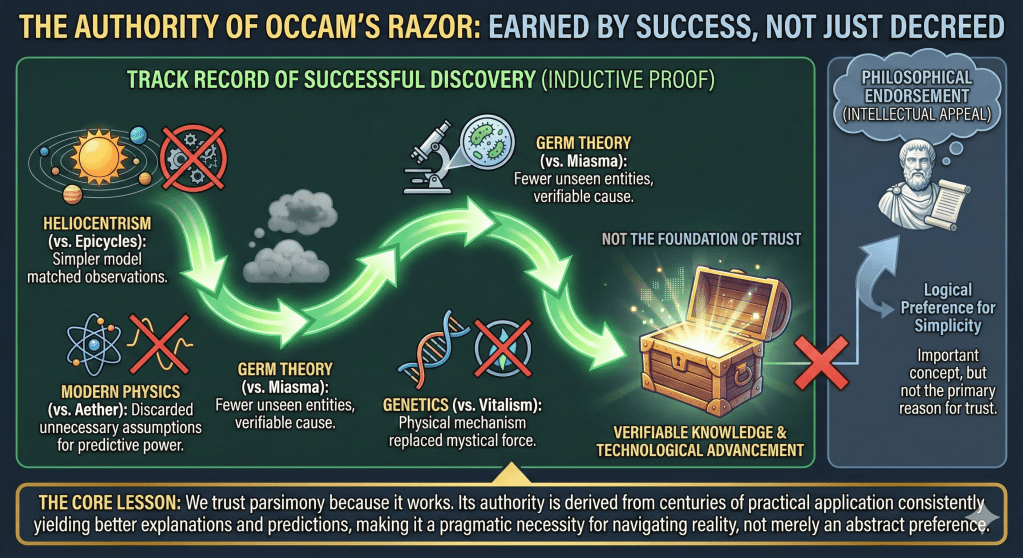

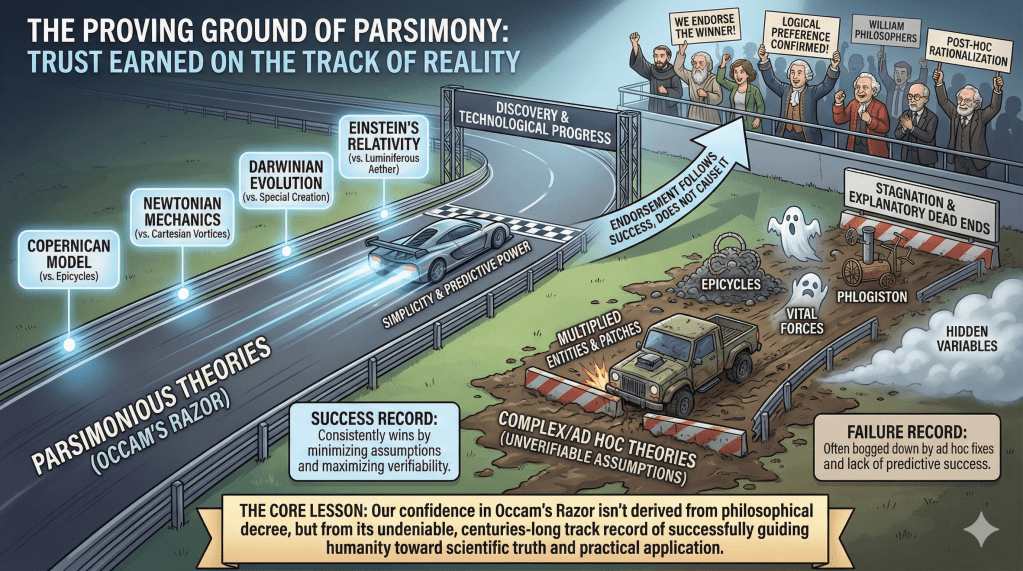

William of Ockham, a 14th-century friar, famously stated: “Pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate”—plurality should not be posited without necessity. In modern terms, among competing hypotheses that predict the same phenomena, the one requiring the fewest novel entities or ad hoc assumptions is most likely to be correct.

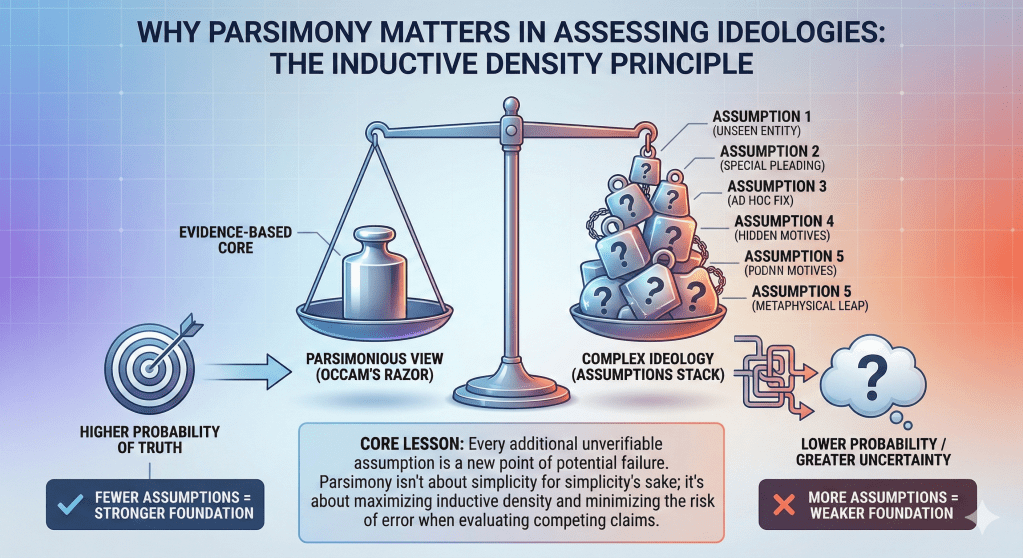

It’s Not About Aesthetics; It’s About Probability

Parsimony is not just an aesthetic preference for minimalism. It has what philosophers call high inductive density. The history of human inquiry—from physics to biology to criminal forensics—demonstrates that explanations requiring fewer unverifiable leaps are statistically more likely to match reality.

Every time you introduce a new, unobservable entity to explain a phenomenon, you introduce a new opportunity to be wrong.

If your car doesn’t start, Hypothesis A is a dead battery. Hypothesis B is that an invisible gremlin is siphoning electrons from the starter motor. Both explain the phenomenon (the car won’t start). But Hypothesis B requires positing a new ontological category (gremlins) that has no precedent in established reality. Parsimony demands we exhaust Hypothesis A before even entertaining B.

In the debate between naturalism and theism, naturalism is the dead battery hypothesis. Theism is the gremlin hypothesis, multiplied by infinity.

2. The Theological Assumption Stack

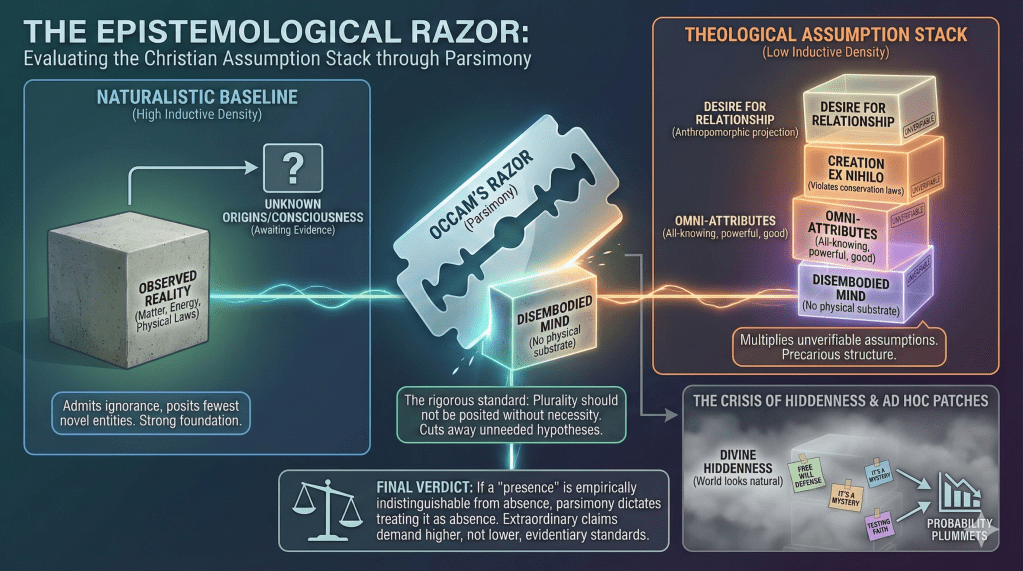

When a naturalist looks at the universe, they assume the existence of the physical reality we observe and the regularities (laws of physics) that govern it. That is the baseline.

When a Christian theist looks at the same universe, they accept the baseline physical reality, but then pile a massive, precarious stack of additional, unverifiable metaphysical assumptions on top of it to explain why the baseline exists.

Let us rigorously examine the “ontological cost” of this stack.

Layer 1: The Base Assumption—A Disembodied Mind

The foundational leap of theism is the assertion that consciousness can exist apart from a physical substrate. Everything we know about minds from neuroscience, psychology, and medicine indicates that consciousness is an emergent property of complex biological brains.

To posit a “God” is to assume the existence of a mind that has no brain, no body, no energy source, and no location in spacetime. This is not a small step; it is a massive break from all observed reality, introducing a completely novel ontological category.

Layer 2: The Attribute Multipliers (Omni-Max)

Having assumed a disembodied mind, the stack immediately grows more complex. This mind is not just existing; it is assigned infinite attributes:

- Omniscience: Knowing every fact, past, present, and future simultaneously.

- Omnipotence: Unlimited power to act.

- Omnibenevolence: Perfect moral goodness.

Each of these attributes is conceptually difficult to define without contradiction (e.g., can an omnipotent being create a rock so heavy he cannot lift it?), and none have any empirical precedent. We have multiplied the complexity of our initial unverified assumption by infinity three times over.

Layer 3: The Mechanism—Creation Ex Nihilo

How does this disembodied, omni-max mind interact with physical reality? The theological claim is creation ex nihilo—out of nothing.

We observe conservation of energy and matter in the natural world. We have never observed “nothing” becoming “something” through an act of will. To posit this mechanism is to assume a causal power that violates our fundamental understanding of physics. It is a “skyhook” explanation—a miraculous intervention inserted where our current knowledge ends.

Layer 4: The Anthropomorphic Turn—Desire for Relationship

So far, we have a deistic abstraction. But the Christian stack requires much more. It assumes this infinite, timeless, immaterial Ground of Being has specifically human-like emotional desires: it wants a “personal relationship” with one species of primate on a small planet in an average galaxy.

This is perhaps the most inductively improbable layer. It requires compressing the infinite into the finite, attributing human concepts of love, jealousy, anger, and desire to a being vastly beyond such biological constraints.

3. The Crisis of Hiddenness and the “Ad Hoc” Rescue

If we accept the towering stack of assumptions above, we immediately run into an empirical crisis.

If there exists an omnipotent, omnibenevolent being who desperately desires a relationship with us, the expected observation would be unambiguous clarity. His existence and his desires should be as obvious as the existence of the sun.

Instead, we observe what philosophers call Divine Hiddenness. We see a world that looks exactly as it would if there were no god involved at all: events governed by natural laws, randomness, and human agency.

The Ad Hoc Patch

To save the assumption stack from collapsing under the weight of contradictory observation (hiddenness), theology must invent new assumptions. These are known as ad hoc hypotheses—explanations created solely to save a theory from falsification, with no independent evidence to support them.

Common Christian ad hoc rescues for hiddenness include:

- “He hides to preserve our free will.” (An unverified assumption about the mechanics of belief).

- “He is testing our faith; belief without seeing is virtuous.” (An unverified assumption about divine morality).

- “His ways are higher than our ways; it’s a mystery.” (An admission that the theory fails to explain the data).

The Parsimony Penalty: Every time an ad hoc hypothesis is added to explain why the previous assumptions don’t match reality, the probability of the entire worldview being true plummets.

4. Addressing Metaphysical Evasions

When pressed with the razor, sophisticated theologians often retreat into metaphysical abstraction to dodge epistemological scrutiny.

Evasion A: “God is not a being, but the ‘Ground of Being’.”

The Response: This is a linguistic shell game. If this “Ground of Being” has a will, issues commands, loves humans, and incarnated as Jesus, then for all practical purposes, it is acting as a discrete entity/agent. Labeling it abstractly does not remove the requirement for evidence of its agency. If it does not have those personal attributes, then it is functionally indistinguishable from naturalistic pantheism or simply the laws of physics, and the Christian framework collapses anyway.

Evasion B: “You can’t compare God to an invisible teapot. God explains everything; the teapot explains nothing.”

The Response: This misses the point of Russell’s Teapot analogy. The analogy is not comparing the function of God and a teapot; it is comparing their method of verification. Both claims—an invisible orbital teapot and an invisible transcendent deity—share an identical epistemological deficit: they are unfalsifiable assertions that lack empirical support.

Elevating a claim to the status of “ultimate reality” does not grant it an exemption from evidentiary standards. To the contrary, extraordinary claims demand vastly higher inductive density than mundane ones.

Conclusion: The Courage of Inductive Density

The application of parsimony to Christian assumptions is not an exercise in cynicism, but in intellectual rigor.

The naturalistic worldview admits that there are things we do not know (e.g., what came “before” the Big Bang, the hard problem of consciousness). It leaves those spaces blank until evidence arrives.

The theological worldview, by contrast, fills those blanks with a dense, precarious architecture of unverified assumptions—disembodied minds, omni-attributes, miraculous mechanisms, and ad hoc excuses for why none of it is visible.

Parsimony dictates that if a proposed “presence” is utterly indistinguishable in all measurable ways from “absence,” rational inquiry must treat it as absence until compelled by evidence to do otherwise. Complicated theological explanations for why an omnipotent God looks exactly like an empty room are not profound insights; they are the inevitable symptoms of a hypothesis that has failed to meet its burden of proof.

Leave a comment