Why “Warrant” is an Epistemic Downgrade: A Mathematical Proof

In philosophy, we are obsessed with trophies. We don’t just want to believe things; we want to know them. We treat “Knowledge” as the gold medal of cognition—a magical state that is qualitatively different from just having a pretty good guess.

For decades, the heavyweight champion of this view has been Alvin Plantinga. His theory of “Warrant” is brilliant, sophisticated, and, I believe, fundamentally broken.

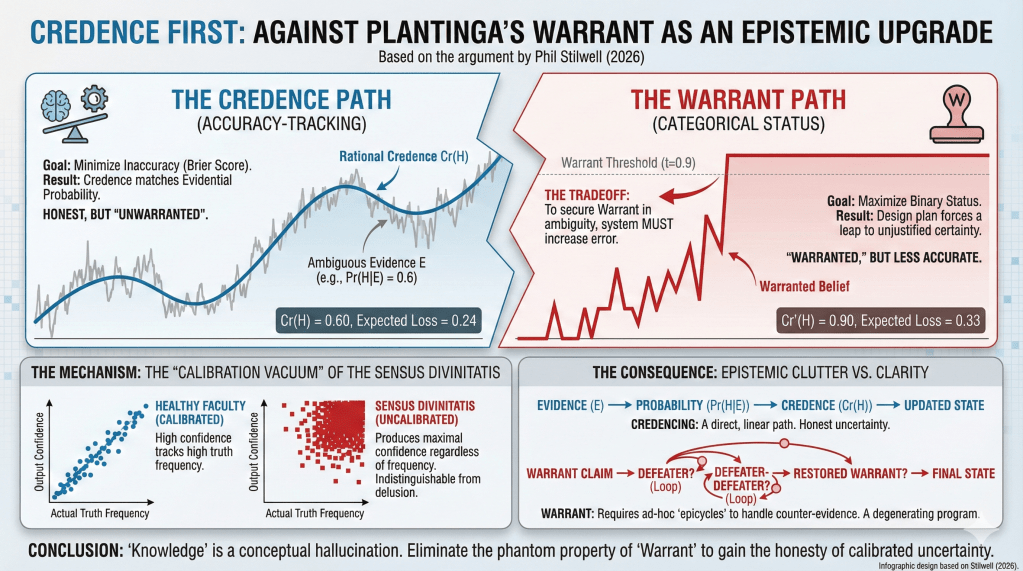

I recently finished a paper, Credence First, where I argue that “knowledge” is actually a conceptual hallucination. It’s a linguistic artifact that confuses us more than it helps. To show why, I ran a formal proof demonstrating that if you design a mind to get Plantinga’s “Warrant,” you firmly require that mind to be less accurate about the world.

Here is the breakdown of why aiming for knowledge actually makes us dumber.

The Obsession with “The Badge”

Plantinga’s theory solves a lot of technical problems in philosophy (like the Gettier problem) by moving the goalposts. He argues that you have Warrant (and thus knowledge) if your belief is produced by:

- Properly functioning faculties…

- …operating in the environment they were designed for…

- …according to a design plan aimed at truth.

If you meet these criteria, you get the badge. You don’t just believe; you know.

This sounds great on paper. But there is a hidden cost.

The Accuracy vs. Warrant Trade-off

Let’s look at this mathematically (but simply).

Imagine you are looking at some ambiguous evidence. Maybe you’re looking at historical data about a miracle, or complex arguments for a political policy. The evidence is leaning “Yes,” but it’s messy. Let’s say the probability based on the evidence is 60%.

You now have two options for how to form your belief.

Option A: The Accuracy Approach (Credencing) Your goal is to map reality exactly as it is. Since the evidence is 60%, you set your confidence at 60%.

- Result: You are perfectly calibrated. You are honest about the uncertainty.

- The Problem: 60% isn’t “knowledge.” It’s a guess. You don’t get the “Warrant” badge because you aren’t “settled” or firm enough.

Option B: The Warrant Approach Your goal is to achieve Warrant. Plantinga requires a belief to be “firmly held” or “settled” to count as knowledge. Let’s say the threshold for “settled” is 90% confidence. To get the badge, your brain must push your confidence from 60% up to 90%.

- Result: You get the badge! You “know” it (assuming it turns out to be true).

- The Problem: You have deliberately miscalibrated yourself. The evidence only supported 60%, but you are feeling 90%. You are now arguably delusional.

This is the central irony: To secure Warrant, the system must be designed to punish accuracy.

In my paper, I used a scoring rule called the Brier Score, which measures the distance between your belief and the truth. It proves that a mind designed to chase Warrant will, in ambiguous situations, generate more error than a mind that just tries to track the evidence honestly.

The “God-Sense” and the Calibration Vacuum

Plantinga applies his theory to religion using something called the Sensus Divinitatis (Sense of the Divine). He argues this is a cognitive module that, when triggered (like when looking at a starry sky), immediately produces a belief in God.

He claims that if this module is working properly, the belief is Warranted.

But here is the catch: Phenomenology is not Probability.

From the inside, the Sensus Divinitatis just feels like certainty. It pushes your confidence dial to 100%. But unlike your eyesight or your hearing, you can’t check it against anything.

- If your eyes tell you “there is a cat,” you can reach out and touch the cat. You can calibrate your eyes.

- If your God-sense tells you “God exists,” you cannot step outside the universe to check.

The Sensus Divinitatis operates in what I call a Calibration Vacuum. It produces maximum confidence regardless of the evidence.

If I built a fuel gauge for your car that read “FULL” regardless of how much gas was in the tank, you wouldn’t say the gauge was “warranted.” You would say it was broken. Plantinga’s theory tries to tell us that if the gauge was designed to always read “FULL,” then you “know” you have gas.

Abandoning “Knowledge”

The solution to this mess is radical but liberating: Eliminativism.

We should stop talking about “knowledge” entirely in rigorous contexts. It’s a folk concept, like “sunrise”—useful for casual conversation, but scientifically false (the sun doesn’t rise; the earth spins).

Instead, we should focus on Credencing.

- What is the evidence?

- What is the probability?

- Does my confidence match that probability?

If we do this, we lose the comfort of saying “I know X.” But we gain the honesty of being calibrated to reality. We trade the illusion of a destination for the utility of an accurate map.

The full paper, “Credence First: Against Plantinga’s Warrant as an Epistemic Upgrade,” includes the formal proofs and is available for those interested in the technical details.

Leave a comment