◉ How the Brief Death of Jesus Failed to Redeem Sinners from their Deserved Eternal Damnation

TL;DR Version

Introduction

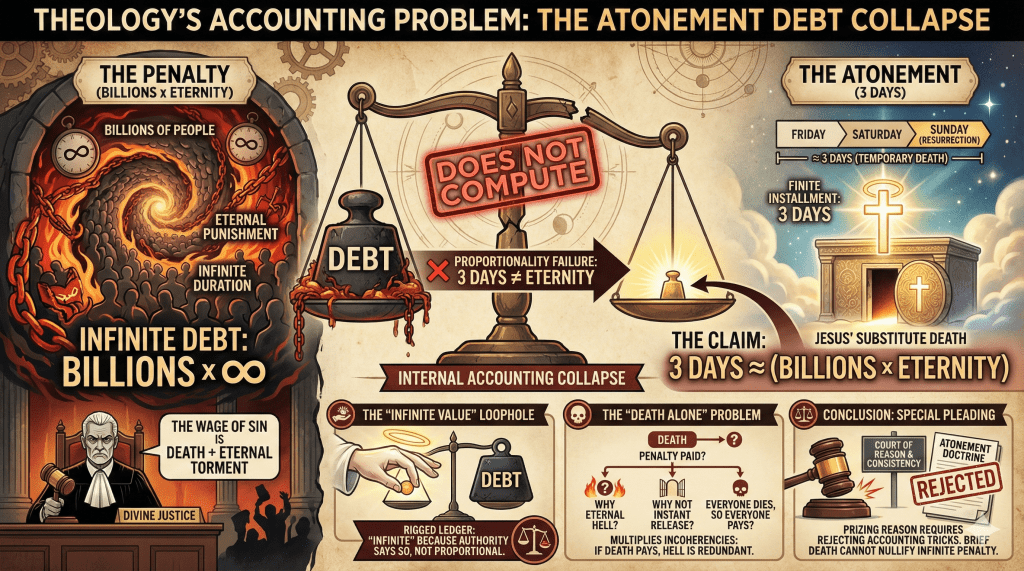

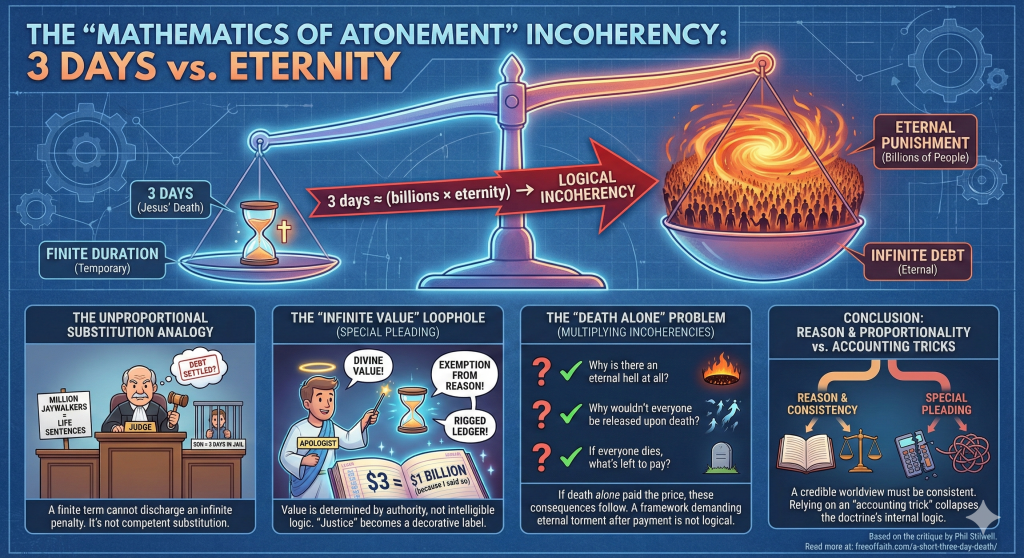

The Christian doctrine of substitutionary atonement—the idea that Jesus died to pay the penalty for all human sin—has long been central to Christian theology. According to this view, all human beings deserve an eternal penalty for their wrongdoing, but Jesus’ three-day death (followed by his resurrection) somehow satisfies this infinite punishment on behalf of billions of sinners. This claim, however, poses serious logical, mathematical, and conceptual problems.

A coherent system of justice demands proportionate penalties. If a punishment is infinite in duration and severity, can a finite suffering of merely three days logically or justly serve as its equivalent? This essay rigorously examines the logical inconsistencies, proportional disparities, and the underlying assumptions that challenge the coherence of substitutionary atonement. By exploring analogies, symbolic logic, and the responses of Christian apologists, it demonstrates that equating a finite death with infinite penalties is mathematically and logically untenable.

The Core Disparity: Finite vs. Infinite Punishment

At the heart of the critique is the claim that eternal damnation—the supposed penalty for sin—is infinitely greater in scope than a short-lived punishment. If billions of sinners each deserve infinite punishment, then the aggregate penalty is effectively unbounded. Yet, Christian theology posits that three days of death suffered by Jesus somehow “covers” all these infinite penalties.

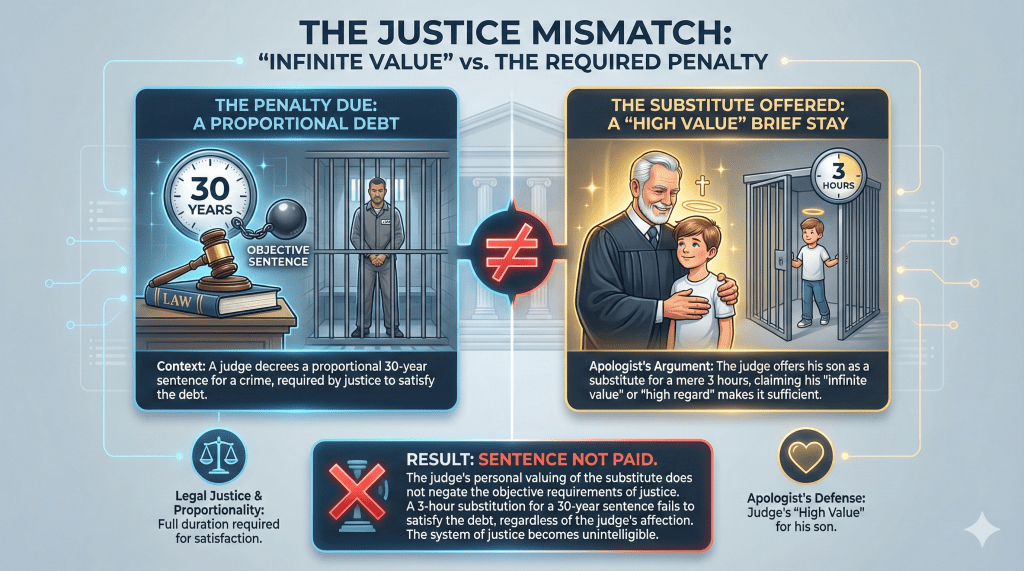

By analogy, if a judge decrees a lifetime of severe discomfort for every jaywalker, then jails one million of them for life, it would be absurd for the judge to later say, “My beloved son served three days in prison, so now all a million life-sentences are considered fully served.” Such a claim contradicts the principle of proportionality and raises doubts about both justice and mathematical coherence.

Logical Formulations and Symbolic Analysis

To highlight the incoherence, consider the following logical forms. Let

Variable and Predicate Definitions:

“x deserves an eternal (infinite) penalty.”

In other words,indicates that the rightful penalty assigned to x is infinite in duration.

“Jesus is designated or attempts to pay the penalty.”represents the proposition that Jesus is the one tasked (or chooses) to atone for the eternal penalty.

“Jesus suffers for 3 days.”is a function or predicate indicating the duration of suffering. It states that Jesus experiences suffering for exactly three days.

This is a statement that the penalty in question is infinite in duration. When related to, it means if

holds, then the penalty required for x is infinite.

“It is not the case that Jesus deserves (or fulfills) an eternal penalty.”indicates that the conditions for Jesus incurring or satisfying an eternal (infinite) penalty are not met.

In summary:

– x’s required penalty is eternal.

– Jesus attempts the role of penalty-payer.

– Jesus actually suffers for 3 days.

– The required penalty is infinite in duration.

– Jesus does not, in fact, satisfy an eternal penalty requirement.

In symbolic form, the challenge is:

where J stands for Jesus.

Yet we are expected to conclude: meaning that if Jesus pays the penalty for x, Jesus must have served that infinite penalty.

But cannot logically equal an eternity

This is the central mathematical inconsistency.

Proportionality and the Principle of Commensurate Justice

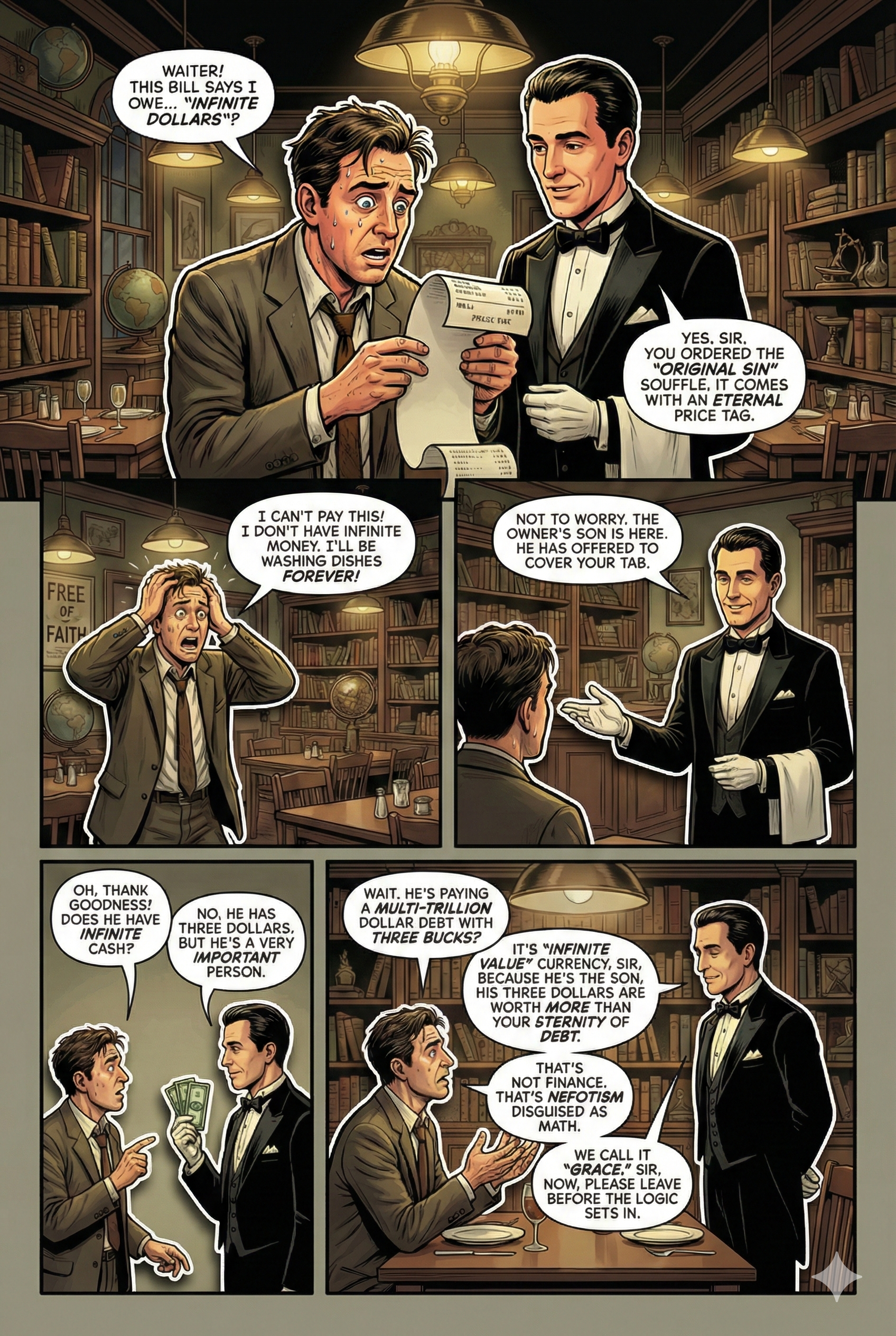

Commensurate justice dictates that the severity and duration of punishment should correspond to the severity of the wrongdoing. If sin truly warrants eternal punishment, then a finite payment cannot justly substitute. Reducing an infinite penalty to a three-day punishment violates the principle of equivalence. Just as one cannot settle a billion-dollar debt with three dollars, one cannot satisfy eternal penalties with a three-day death.

Analogies Illustrating the Incoherence

Analogy 1: The Restaurant Bill

Imagine 1,000 diners each owe $1,000—a total of $1,000,000. A benefactor steps in, pays $3 total, and the restaurant declares the entire million-dollar debt cleared. This violates fundamental principles of fairness and mathematics. Likewise, three days of death cannot logically equate to infinite penalties.

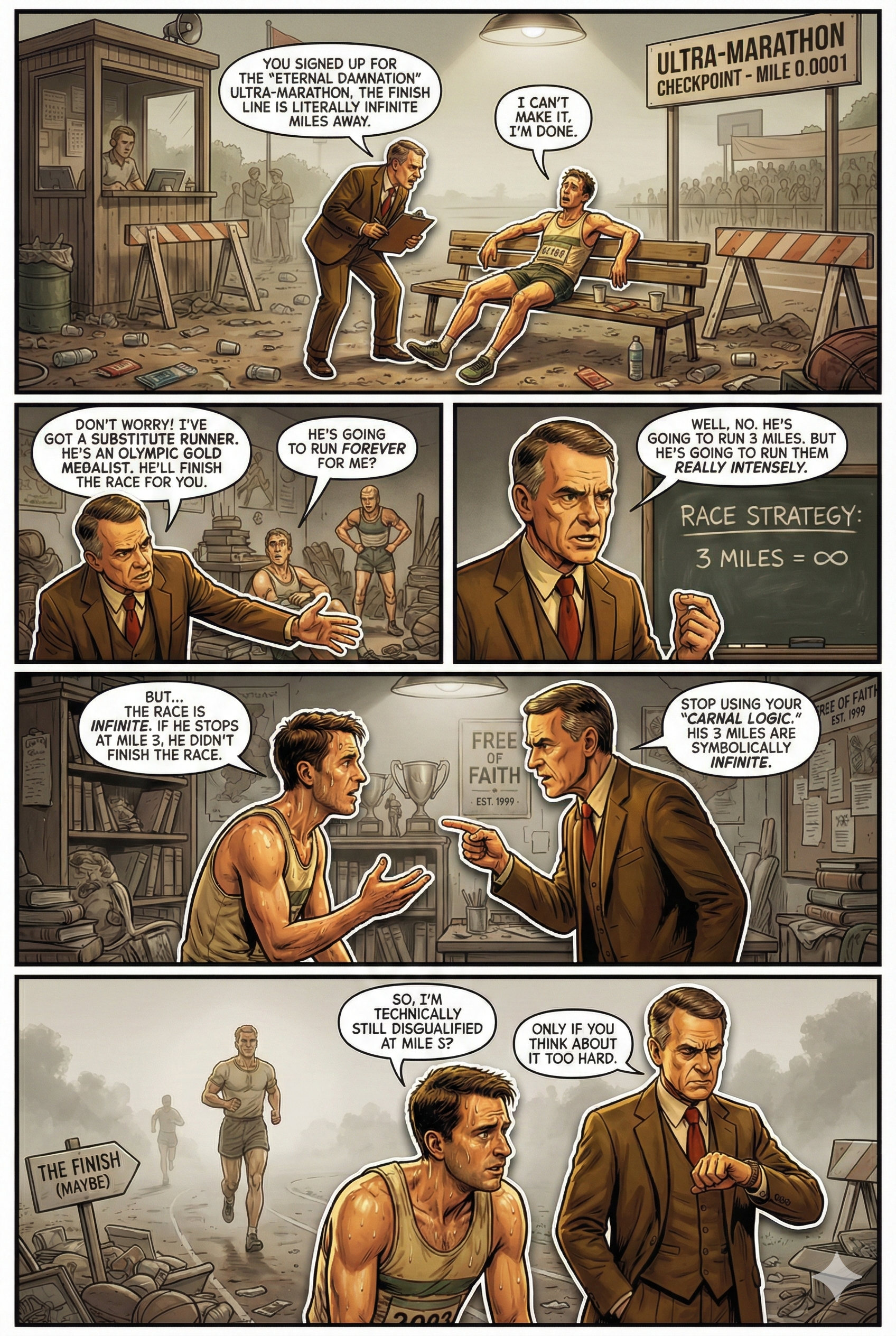

Analogy 2: The Substitute Runner

A marathon requires running 26.2 miles. If a coach runs only 3 miles for a sick athlete and claims to have completed the entire race, the claim is obviously false. Similarly, three finite days of death cannot be said to complete an infinite punishment.

Analogy 3: The Broken Loan System

A bank loans millions of people lifetime repayment plans. The CEO’s child works three days at minimum wage, and the bank declares all loans forgiven. Clearly, this fails to meet standards of proportionality or reason. The Christian atonement claim is structurally similar—an incomplete equivalence disguised as a completed payment.

The Innocence Factor and Substitutionary Justice

Some Christians argue that Jesus’ innocence or divine nature grants infinite value to his suffering. However, assigning infinite worth to a finite event does not mathematically convert a finite quantity into an infinite one. If infinite penalties are at stake, then the actual payment should reflect infinite magnitude. The innocence or status of the substitute cannot bridge this logical gap.

Furthermore, punishing an innocent being for others’ crimes contradicts principles of fairness. Even if one sets aside the question of whether substitution itself is just, the lack of a proportional equivalence remains unresolved.

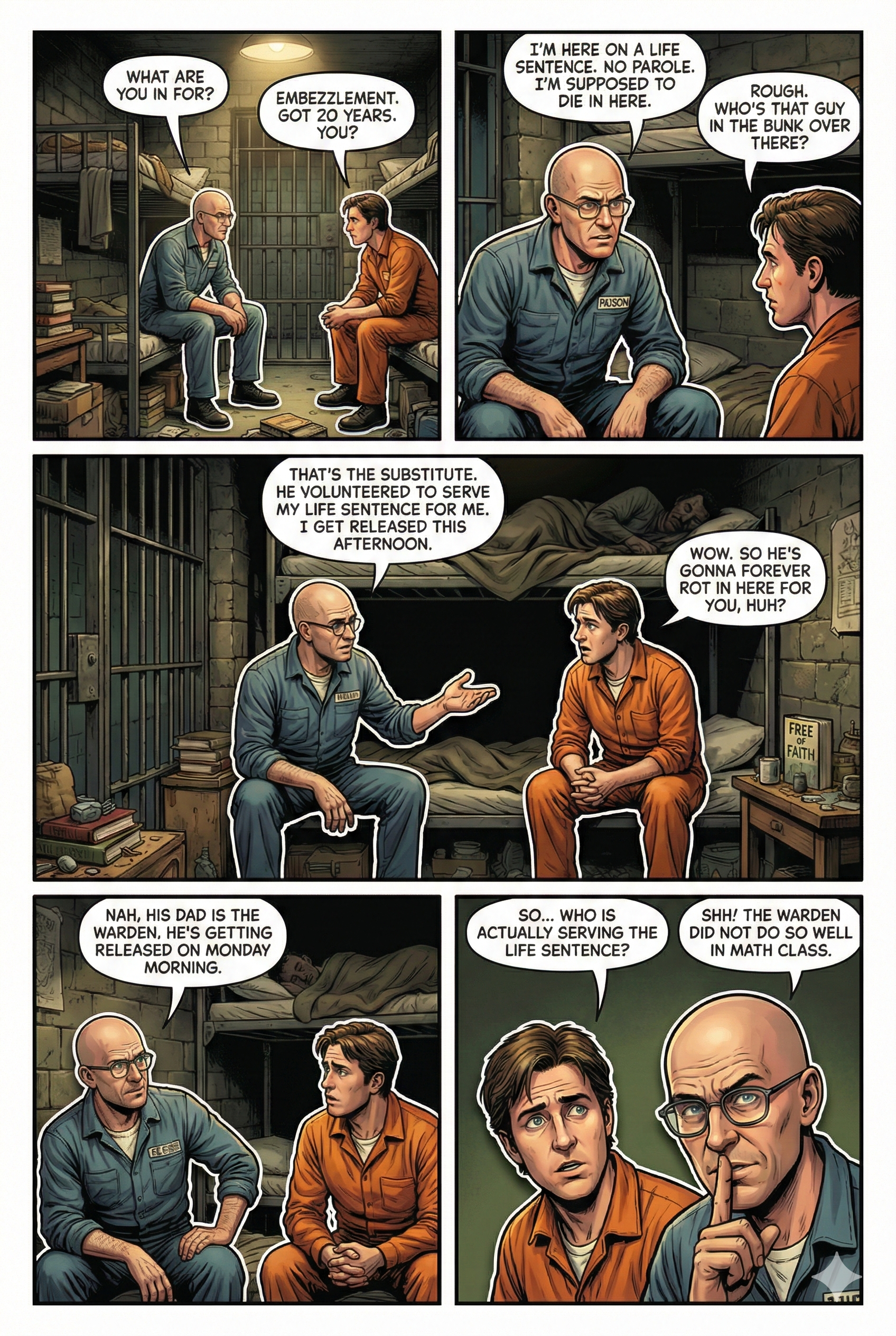

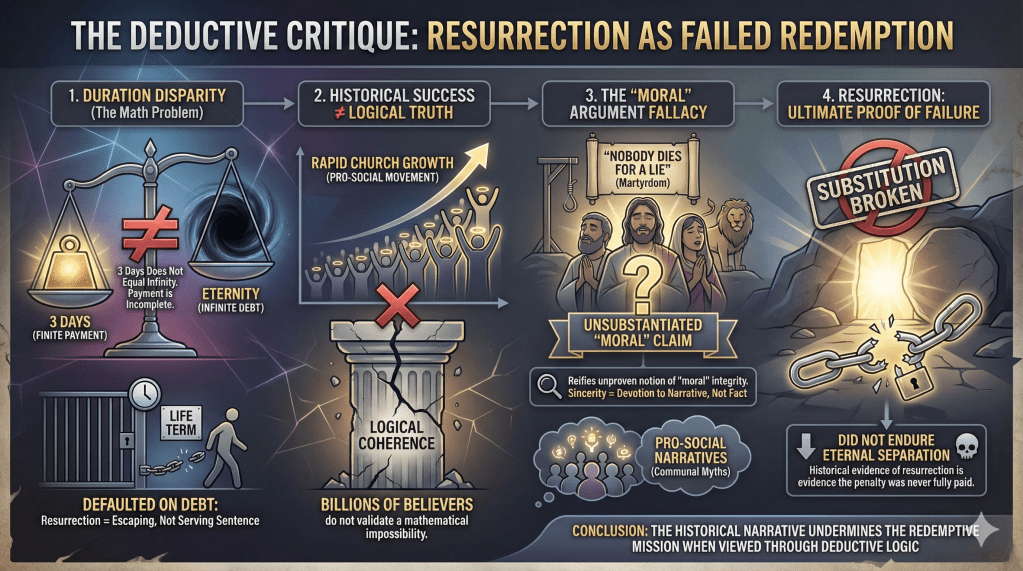

The Resurrection and Completion of the Penalty

The doctrine claims that Jesus’ death pays the penalty in full, yet Jesus resurrected after three days. If the required penalty is eternal death, then resurrecting after three days signifies the penalty was not fully served. In any system of justice, releasing a prisoner well before completing their life sentence is not equivalent to serving the entire sentence. By analogy, a three-day death simply cannot be the full measure of eternal punishment.

If the penalty is truly eternal separation from God, then escaping that separation by resurrection means the penalty was never actually endured to its full, infinite extent.

Common Theological Responses and Their Limitations

Response 1: Infinite Value of Jesus’s Sacrifice

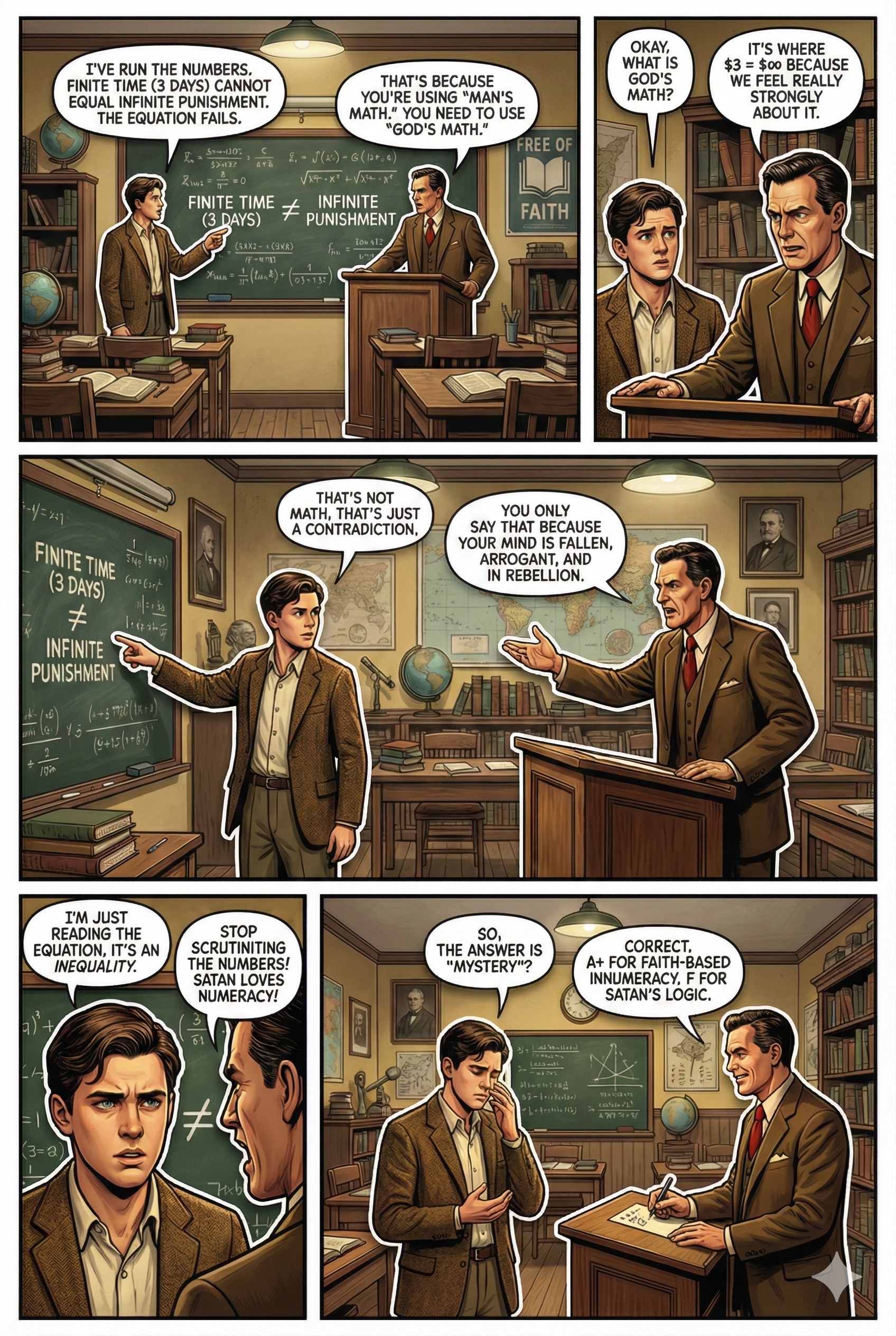

The claim that Jesus’ divine nature imparts infinite value to his suffering attempts to override logical scrutiny with an undefined concept of “infinite value.” Without a coherent metric linking infinite value to infinite duration, this becomes special pleading rather than a reasoned solution.

Response 2: God’s Sovereignty and Mystery

Invoking divine sovereignty or the “mystery” of God’s ways sidesteps the logical problem rather than addressing it. If the principles of justice are defined as whatever God decrees, then the concept of divine justice becomes unfalsifiable and potentially arbitrary.

Response 3: Symbolic Rather Than Literal

Some argue the atonement is symbolic. While this may resolve the numerical mismatch, it undermines the literal claim that Jesus truly paid the infinite penalty. A purely symbolic interpretation abandons the original doctrinal intent, leaving the infinite vs. finite puzzle unsolved.

Formal Logical Arguments

Argument 1: Duration Disparity

- Premise 1: If the penalty is eternal, any just payment must also be eternal.

- Premise 2: Jesus’ penalty lasted only three days.

- Conclusion: Therefore, Jesus did not pay an eternal penalty.

Expressed symbolically:

Therefore:

Argument 2: Substitutionary Proportionality

- Premise 1: Substitutionary justice requires proportionality between punishment and offense.

- Premise 2: Billions of sinners merit infinite punishment.

- Premise 3: Jesus’ three days of death is finite and thus not proportional to infinite punishment.

- Conclusion: Substitutionary justice fails as a coherent explanation.

Argument 3: Innocence and Logical Justification

- Premise 1: Innocence does not alter the amount of penalty needed.

- Premise 2: Infinite penalty remains infinite, regardless of who suffers it.

- Conclusion: Jesus’ innocence does not justify equating three finite days with infinite penalties.

Implications for Theological Consistency

If the penalty for sin is indeed eternal, then any claim that it was fully paid by a finite event is logically and mathematically incoherent. Either:

- The penalty is not truly eternal, and thus must be redefined, or

- Jesus’ act did not actually pay the full penalty, leaving the doctrine’s foundational claim unfulfilled.

This dilemma forces a reconsideration of the doctrinal structure. If God’s justice is non-arbitrary, proportional, and meaningful, then the atonement, as classically presented, must be rethought to preserve logical and moral consistency.

Conclusion

The assertion that Jesus’ three-day death atones for the eternal damnation of billions is fraught with logical and mathematical inconsistencies. Finite suffering cannot stand in for infinite punishment without eroding basic principles of proportional justice. While theological explanations invoke infinite value, divine sovereignty, or mystery, these responses fail to provide a coherent mechanism by which a three-day event can neutralize countless eternities of owed punishment.

Ultimately, a rigorous, comprehensive, and logically coherent analysis reveals that the classical substitutionary atonement model, as commonly understood, does not withstand scrutiny. For those who value logical consistency and equitable standards of justice, this discrepancy demands an honest reexamination of the doctrine’s foundational assumptions.

Other Incoherencies Found within the Christian Notion of Redemption

Introduction

The Christian concept of redemption encompasses more than just the finite vs. infinite punishment dilemma. It also includes doctrines such as the necessity of blood sacrifice, the efficacy of vicarious suffering for the sins of others, and the foundational idea that forgiveness must hinge upon a violent or painful event. These notions, while central to traditional Christian theology, present a host of logical and ethical incoherencies. By exploring these issues, we can better understand why the conventional portrayal of redemption may fail to cohere with rational principles of justice, morality, and proportionate accountability.

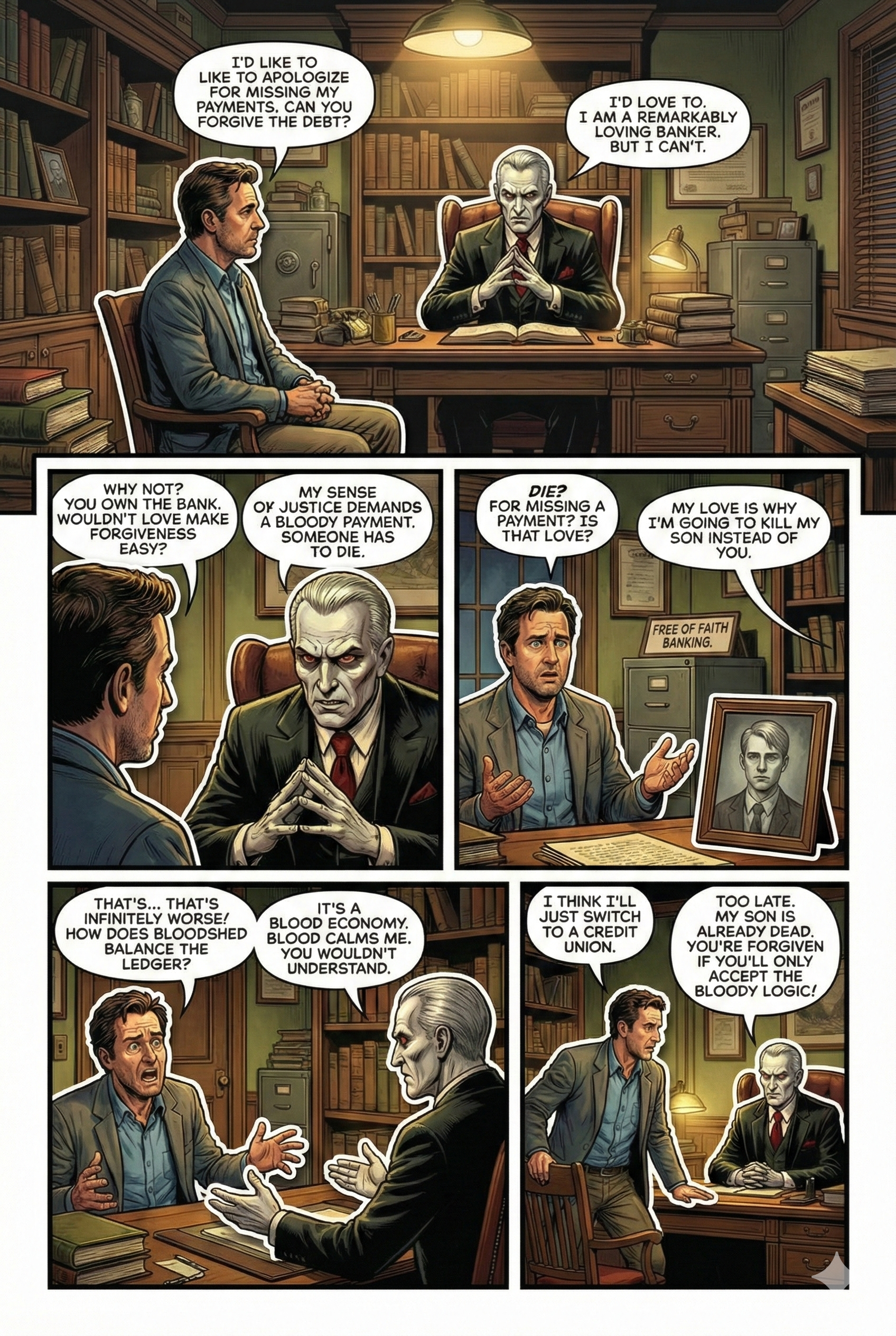

The Need for Blood and Suffering in Forgiveness

A core tenet in much of Christian thought is that sin cannot be forgiven without the shedding of blood. This principle is often justified by citing biblical texts that insist on the necessity of sacrificial blood for atonement. However, this concept raises profound questions:

- Why Must Suffering Precede Forgiveness?

In ordinary human relationships, forgiveness need not be contingent on violence or suffering. People can and often do forgive one another out of compassion, empathy, or a desire to restore harmony. If human beings can forgive without demanding a blood payment, why can’t an all-powerful and loving deity do the same? - Moral Implications of Blood Requirements

Requiring bloodshed as a precondition for forgiveness implies a system in which violence and harm become a currency for moral debt. This stands in stark contrast to the intuitive understanding that forgiveness is a voluntary relinquishing of resentment or moral debt. Attaching a mandatory suffering component suggests that the divine nature is bound by a rule that is not only arbitrary but also morally questionable. - Equating Blood with Moral Cleansing

The premise that blood cleanses sin presupposes a mystical or metaphysical economy where wrongdoing can be offset by pain or death. This reduces morality to a ledger balanced by suffering. Such a scheme lacks coherence if we regard moral offenses as requiring relational healing or reparative actions rather than violent currency.

The Injustice of Vicarious Punishment

The notion that one person can bear the punishment for another’s offenses raises both ethical and logical issues. Central to the Christian redemption narrative is the idea that Jesus, an innocent party, can justly suffer on behalf of the guilty. This concept faces several challenges:

- Undermining Personal Accountability

If an innocent individual can be punished in place of the guilty, then the principle of personal accountability—fundamental to any just system—is undermined. True justice requires that the individual who commits the offense be the one to face the consequences. Reassigning punishment disconnects the offender from their due penalty, effectively nullifying the core purpose of just retribution or rehabilitative justice. - Moral Repugnance of Punishing the Innocent

Punishing an innocent person is generally regarded as inherently unjust, a principle that is widely accepted across moral and legal frameworks. To claim that it can become just in a divine scenario contradicts the very definition of justice as understood in almost every human context. - Failure to Address the Root Problem

Vicarious punishment does not correct the character, intentions, or future behavior of the offender. Instead, it simply transfers the negative consequence to another party. This does not restore moral balance in any meaningful sense, nor does it promote genuine moral growth or reconciliation between the offender and the offended.

The Logical Disconnect Between Divine Omnipotence and Required Sacrifice

If the Christian God is omnipotent, possessing unlimited power and authority, the insistence on a sacrificial system for redemption seems incoherent:

- Unnecessary Constraints on Divine Forgiveness

An all-powerful deity, by definition, has the capacity to forgive transgressions freely. If limitations exist—such as a required blood payment—they suggest that God is bound by some external principle or law that overrides divine benevolence. This implies that God is not truly sovereign over the moral order, contradicting claims of ultimate authority and freedom. - Arbitrariness of Redemptive Conditions

If forgiveness can only be achieved through a painful sacrifice, why this specific mechanism? The selection of bloodshed as the required form of atonement appears arbitrary. Could an omnipotent being not establish a more coherent and less violent pathway? The arbitrariness points to a lack of logical necessity, undermining the credibility of the entire sacrificial framework.

The Compatibility of Divine Love and Required Violence

Christianity often upholds a vision of God as love, suggesting that God’s nature is fundamentally characterized by compassion, mercy, and desire for human flourishing. However:

- Contradictory Traits

If divine love is unconditional, why impose a system that conditions forgiveness on violence or suffering? One would expect a loving deity to prefer reconciliation that avoids inflicting additional pain. The insistence on blood sacrifices or a violent death (in the case of Jesus) stands at odds with the idea of a perfectly loving and benevolent God. - Emotional Manipulation and Human Psychology

The violent elements of redemption narratives can function as emotional leverage. Followers are sometimes encouraged to feel indebted to a savior who endured unjust suffering on their behalf, thereby creating psychological pressure rather than promoting free, rational moral development. This raises the question of whether the narrative’s coherence is compromised by reliance on emotional coercion rather than clear, logical reasoning.

The Question of Infinite Penalties for Finite Beings

Beyond the three-days-in-lieu-of-infinity issue, the underlying assumption that finite creatures, who commit finite offenses, merit infinite punishment remains conceptually dubious:

- Proportionality of Punishment

If a finite being, limited in both capacity and lifespan, cannot produce infinitely harmful outcomes, attributing an infinite penalty to their offenses seems grossly disproportionate. A just system would match penalty severity to the nature and extent of the wrongdoing. - Moral Development vs. Eternal Retribution

If the goal of a moral system is to foster growth, change, and reconciliation, then condemning beings to eternal punishment (and requiring a violent sacrifice to offset it) achieves none of these aims. It neither reforms the sinner nor provides a coherent rationale for why infinite penalties are warranted.

Theological Responses and Their Shortcomings

Proponents of the sacrificial redemption model often invoke mystery, divine sovereignty, or the infinite worth of Christ’s sacrifice. However:

- Appeal to Mystery

Invoking mystery avoids the problem rather than solving it. Without a clear explanation, the system remains logically questionable, prompting the skeptic to view the doctrine as a series of assertions lacking transparent rational underpinning. - Divine Authority as a Justification

Claiming that God’s ways are higher than human ways can sidestep legitimate questions about justice and coherence. If “just because God says so” is the final answer, it reduces morality to divine fiat rather than reasoned principle, ultimately rendering the concept of divine justice arbitrary. - Infinite Worth vs. Logical Equivalence

Suggesting that the infinite worth of the divine being elevates a finite sacrifice into an infinite one sidesteps the structure of rational equivalence. Worth cannot be a stand-in for logical proportionality. Without a coherent mechanism to translate qualitative worth into quantitative payment, the argument remains incomplete.

Implications for Ethical and Rational Credibility

If the redemption narrative hinges on bloodshed, vicarious punishment, and infinite penalties for finite sins, all defended by appeals to mystery and authority, its ability to present a credible, morally coherent framework is diminished. Ethical systems that privilege reason and fairness find these doctrines incompatible with foundational principles of justice and morality.

Conclusion

The issues embedded in the Christian notion of redemption extend beyond the temporal disparity between Jesus’ three-day death and eternal punishment. They encompass the necessity of violence and bloodshed for forgiveness, the ethical and logical failings of vicarious punishment, the arbitrary constraints placed on divine omnipotence, and the incoherence of infinite penalties for finite beings. These problems highlight fundamental contradictions and raise critical questions about the justice, consistency, and intelligibility of traditional redemption doctrines.

Ultimately, while Christian theology may invoke mystery or divine sovereignty to defend these notions, such appeals do not resolve the underlying logical and moral dilemmas. For those who value logical coherence, moral clarity, and proportional justice, these incoherencies remain formidable obstacles to viewing the Christian narrative of redemption as a rationally consistent and ethically sound system.

Comprehensive Logical Arguments and Symbolic Analyses

This section consolidates and rigorously formalizes the core logical arguments from the preceding discussions.

Argument 1: Finite Substitution vs. Infinite Punishment

Syllogism

- If the penalty for sin is eternal, any just substitute must also endure an eternal penalty.

- Jesus suffered for only a finite period (approximately three days).

- Therefore, Jesus did not fulfill the requirement of eternal punishment.

Variable Definitions:

= “for all x”

= “x deserves an eternal penalty”

= the penalty duration for x

= “Jesus attempts to pay the penalty”

= “Jesus suffers for 3 days”

= “Jesus has justly satisfied the required penalty”

Symbolic Logic

Annotations:

Eternal (infinite) punishment cannot be equated with a finite event. If the required penalty is infinite, fulfilling it in three days is logically impossible.

Argument 2: Vicarious Punishment and Justice

Syllogism

- Justice requires that the guilty face their own penalties.

- Vicarious punishment transfers the penalty from the guilty to an innocent party.

- Therefore, vicarious punishment contradicts the principle of accountability inherent in justice.

Variable Definitions:

= “y is guilty”

= “x is punished for y’s offense”

Symbolic Logic

Annotations:

If a guilty party must bear their own punishment, delegating it to an innocent party violates this requirement. Hence, vicarious punishment is unjust by definition.

Argument 3: Necessity of Blood for Forgiveness

Syllogism

- True forgiveness should release moral debt without imposing new harm.

- The doctrine demands bloodshed (harm) for forgiveness.

- Therefore, requiring harm contradicts the concept of freely given forgiveness.

Variable Definitions:

= “forgiveness occurs”

= “blood/harm required”

Symbolic Logic

Annotations:

If forgiveness ideally entails no further harm, imposing bloodshed introduces a logical inconsistency. Forgiveness cannot require what it aims to eliminate.

Argument 4: Infinite Punishment for Finite Offenses

Syllogism

- A just system uses penalties proportionate to the offense.

- Human sins are finite actions by finite beings.

- Therefore, infinite punishment for finite offenses is disproportionate and unjust.

Variable Definitions: = “x committed a finite offense”

= “x receives an infinite penalty”

Annotations:

Punishing finite offenses infinitely violates proportionality, a cornerstone of fair justice. The result is an illogical disparity.

Argument 5: Omnipotence vs. Required Blood Sacrifice

Syllogism

- An omnipotent being can forgive freely without conditions.

- The doctrine asserts that blood sacrifice is required for forgiveness.

- Therefore, requiring blood constraints an omnipotent being, contradicting true omnipotence.

Variable Definitions:

= “God is omnipotent”

= “forgiveness occurs”

= “blood required”

Symbolic Logic

Annotations:

If God is all-powerful, no external requirement (blood) should limit divine forgiveness. Imposing such a requirement introduces a contradiction.

Argument 6: Appeals to Mystery and Sovereignty

Syllogism

- A logically coherent moral system needs no unresolved mysteries to explain its principles.

- The doctrine invokes divine mystery or sovereignty to justify contradictions.

- Therefore, the doctrine is not logically coherent.

Variable Definitions:

= “system is coherent”

= “mystery invoked to resolve contradictions”

Symbolic Logic

Annotations:

If a system relies on mystery to handle contradictions, it cannot be considered logically consistent. Coherence demands rational clarity.

Integrated Conclusion

- Argument 1: Finite substitution cannot match infinite penalty.

- Argument 2: Vicarious punishment negates accountability.

- Argument 3: Requiring harm (blood) for forgiveness contradicts forgiveness itself.

- Argument 4: Infinite penalty for finite offenses is disproportionate.

- Argument 5: Mandatory conditions contradict omnipotence.

- Argument 6: Appeals to mystery admit lack of logical coherence.

These analyses show that the doctrines, as traditionally presented, fail to maintain a logically coherent framework.

Understanding the Temporal Duration of Jesus’ Death: A Rigorous Analysis

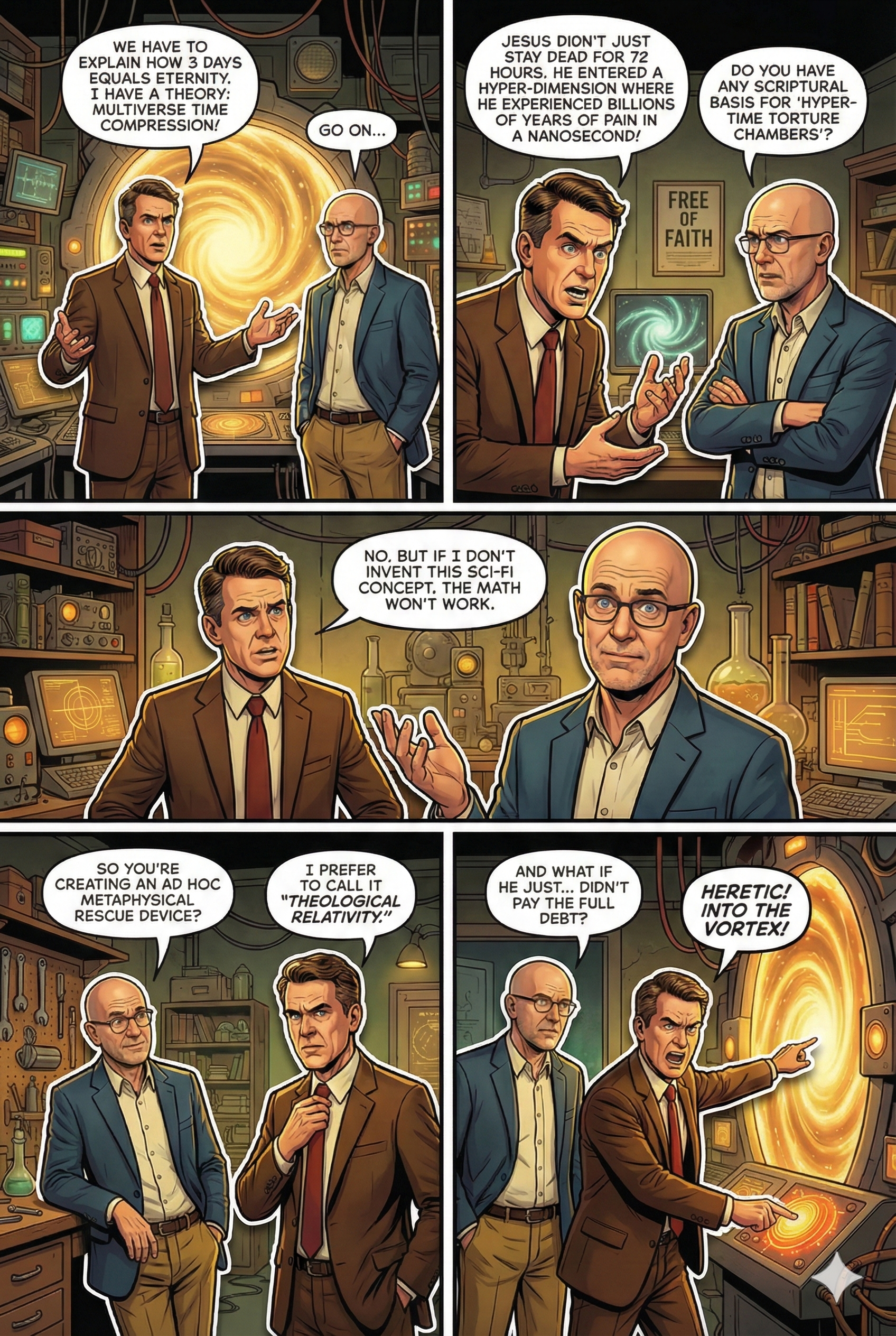

The Christian doctrine of substitutionary atonement hinges on the belief that Jesus’ death serves as the sufficient and final payment for the eternal penalty owed by humanity due to sin. This belief raises significant logical and proportional questions, particularly surrounding the duration of Jesus’ death. If Christians were asked to evaluate whether a 2-day death would be too short or a 4-day death would be too long—and to provide their rigorous reasons—such analysis might shed light on the internal logic and underlying assumptions of this doctrine. In particular, this exercise forces Christians to grapple with the quantitative sufficiency of Jesus’ suffering, the role of time in atonement, and the relationship between infinity (eternal punishment) and finitude (a temporary death).

The Central Question: Why Exactly Three Days?

The duration of Jesus’ death—three days—is treated as divinely ordained and sufficient for the atonement. However, if Christians were asked to assess a deviation from this duration (e.g., a 2-day death or a 4-day death), they would have to address several key concerns:

- Would a shorter duration (2 days) undermine the sufficiency of atonement?

- Would a longer duration (4 days) add unnecessary suffering or signify excessive payment?

- How does the temporal duration relate to the infinite penalty for sin?

Addressing these questions rigorously would force Christians to clarify how the relationship between finite suffering and infinite atonement is established.

The Case of a 2-Day Death: Is It Too Short?

If Christians were to argue that a 2-day death would be insufficient, they would need to provide specific reasons for why three days is necessary and not merely symbolic or arbitrary. The reasoning would likely involve one of the following defenses:

- Symbolic Necessity:

Many Christians claim that the three-day death fulfills prophecies (e.g., Jonah’s three days in the belly of the fish) or symbolizes perfection and completeness. Reducing the duration to two days might be seen as breaking with this symbolic or prophetic necessity.- Counterpoint: If symbolic duration is the primary justification, then it becomes evident that the symbolism of the event—not the actual duration of suffering—dictates its sufficiency. However, if symbolism is sufficient, then the connection between Jesus’ suffering and infinite punishment becomes increasingly tenuous.

- Experiential Sufficiency of Suffering:

Christians might argue that three days provided a qualitative intensity of suffering that sufficiently addressed the infinite weight of sin. A 2-day death might be seen as truncating the intensity or completeness of Jesus’ experience.- Counterpoint: This introduces the question of whether the duration or quality of suffering is what matters most. If experiential quality determines sufficiency, then why is duration significant at all? Wouldn’t a single moment of infinite suffering suffice?

- Divine Fiat:

Some Christians may retreat to divine fiat, asserting that God decreed three days and any deviation would undermine the atonement. In this case, the specific duration becomes an arbitrary divine decision rather than a logical necessity.- Counterpoint: If God’s decree makes three days sufficient, then the intrinsic connection between Jesus’ death and its efficacy for atonement is lost. A 2-day or 4-day death would then be equally viable, rendering any discussion of time irrelevant.

The Case of a 4-Day Death: Is It Too Long?

Conversely, if Christians were asked whether a 4-day death would be excessive, they would have to explain why an additional day of death and suffering would add no further value to the atonement. This reasoning might take several forms:

- Sufficiency Already Achieved in Three Days:

Christians might argue that three days is precisely what was needed—no more, no less. A 4-day death would be unnecessary because the work of atonement was completed.- Counterpoint: If three days achieves infinite atonement, then any additional suffering becomes superfluous. However, this raises a deeper question: why three days? If finite suffering in three days achieves infinite atonement, then logically, even one day—or one moment—should suffice.

- The Resurrection Timeline:

Christians might emphasize that the three days align with the timeline of Jesus’ resurrection and God’s redemptive plan. Extending the death to four days might disrupt the theological narrative of victory over death and the fulfillment of prophecy.- Counterpoint: This response underscores the symbolic and narrative importance of three days rather than any inherent logical or proportional necessity for that specific duration. If the resurrection timeline determines sufficiency, then the death’s duration ceases to have direct relevance to the infinite penalty for sin.

- Unnecessary Suffering:

Christians might argue that an extra day of death and suffering would be excessive and contrary to God’s mercy. Since three days sufficed, additional suffering would serve no purpose.- Counterpoint: This introduces an ethical question: If Jesus’ suffering was intentionally finite, how does it still logically satisfy an eternal penalty? If any amount of finite suffering is sufficient, why is three days specifically necessary, and why not one day instead?

Implications for the Logic of Atonement

Asking Christians to rigorously justify the sufficiency of a 3-day death relative to a 2-day death (too short) or a 4-day death (too long) exposes deeper logical inconsistencies in the atonement doctrine:

- Duration vs. Efficacy:

If the temporal duration of Jesus’ death matters, then Christians must explain why time (a finite concept) can satisfy an infinite penalty. This issue remains unresolved if finite suffering—regardless of its duration—can be considered “infinite” in efficacy. - Symbolism vs. Substance:

Much of the justification for the 3-day duration relies on symbolic or narrative elements (prophecies, completeness, resurrection timelines). If symbolism drives sufficiency, then the suffering itself becomes secondary, undermining claims that Jesus’ death bore a proportional penalty. - Divine Fiat as Arbitrary:

Appealing to divine fiat (“God said three days”) avoids explaining why three days—rather than two or four—is necessary. If God’s decision is arbitrary, then the connection between justice, atonement, and time loses all logical foundation. - Proportional Justice:

If an eternal punishment requires finite suffering to last three days specifically, Christians must explain why neither two days (too short) nor four days (too long) satisfies justice. Without such explanation, the duration appears arbitrary rather than proportionate.

A Hypothetical Path Forward

For Christians to resolve this issue, they would need to rigorously define:

- Why three days—not one, two, or four—is the precise and necessary duration.

- How finite suffering, constrained by time, logically satisfies an infinite penalty.

- Whether symbolism or experiential suffering is the determining factor for sufficiency.

By clearly addressing these points, Christians might establish a more coherent framework for the doctrine of atonement. Such an exercise would not only clarify the logic of Jesus’ death but also illuminate the internal consistency (or inconsistency) of the doctrine itself.

Conclusion

If Christians were asked to determine whether a 2-day death would be too short or a 4-day death would be too long—and to provide rigorous, logical reasons for their stance—it would force them to clarify the principles underlying the doctrine of substitutionary atonement. Such analysis would reveal whether the duration of Jesus’ death has an intrinsic, proportional connection to the infinite penalty it claims to satisfy, or whether it is driven primarily by symbolism, divine fiat, or theological narrative. Addressing this question rigorously would expose the extent to which the doctrine aligns with principles of justice, proportionality, and logical coherence. Without such clarity, the specific three-day duration remains unexplained, raising further doubts about the logical and ethical integrity of the atonement narrative.

Christian Apologetics Group Responses

The discussion in the file on the left was initiated by a 2025 post in a Facebook group called Christian Apologetics. Gemini was solicited to provide the analysis below.

◉ PROMPT:

For each of these interlocutors in the attached file [the full FB thread file above], score their output along these dimensions:

1: Completeness (To what degree is their defense of their position conceptually complete?)

2: Relevance (To what degree is the response relevant to the initial post?)

3: Civility (To what degree does the tone of their response reflect biblical humility and openness?)

Place the scores (0-10) for each interlocutor in one paragraph, and add another paragraph with an 3-4 sentence explanation that exposes any logical incoherencies and major logical fallacies.

◉ GEMINI OUTPUT:

Here is a scored assessment with individualized feedback for each interlocutor.

Andrew Bartlett

Scores: Completeness: 7, Relevance: 8, Civility: 9

Andrew’s argument is one of the more substantive, as he attempts to use mathematics (e.g., “infinity times any finite value is still infinity”) to directly address the critique1. While I identify this as a category error—confusing the qualitative “worth” of a person with the quantitative duration of a punishment—his approach is directly relevant and his tone remains civil and focused on the argument. He engages the core of the problem, even if his solution remains unconvincing by conflating different mathematical and theological concepts.

Leif Egil Rønaasen Reve

Scores: Completeness: 6, Relevance: 7, Civility: 8

Leif’s defense rests on the classic apologetic that Jesus’s divinity makes the logical challenge moot, a move that sidesteps rather than resolves the proportionality problem2. He correctly identifies that his framework renders the duration arbitrary but presents this as a feature, not a bug, of the theology. His argument is relevant but ultimately defaults to an appeal to a presupposed theological status to nullify the mathematical and logical disparity I presented.

Wayne Clarke

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 1

Wayne’s contributions are consistently low in completeness and relevance, relying almost entirely on appeals to scriptural authority, ad hominem attacks (“you wear [Satan’s work] well”), and emotional appeals rather than logical arguments3333. His approach is a clear example of evading the question by attacking the questioner and asserting his conclusion without providing a coherent defense. His aggressive and dismissive tone represents a failure of civil discourse and biblical humility.

David J Wireback Jr.

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 4, Civility: 7

David makes a direct appeal to mystery, stating that the “natural mind cannot comprehend things of God,” which is a classic fideistic defense4. While civil, this response is incomplete because it explicitly sidesteps the demand for logical coherence by declaring the topic off-limits to rational inquiry. It is a polite refusal to engage the argument on the terms of justice and logic.

Bill Elgin

Scores: Completeness: 1, Relevance: 2, Civility: 6

Bill offers a pure assertion, stating that “all the discussions in the world don’t change the Biblical truth that it was enough”5. This is not an argument but a statement of faith that completely bypasses the logical challenge. It lacks any attempt at a complete or relevant defense, simply restating the conclusion I am questioning.

Benjamin Roald Andersen

Scores: Completeness: 5, Relevance: 7, Civility: 9

Benjamin presents a clear and civil argument from divine fiat, proposing that justice is coherent within the Christian framework because God, as the author of logic and morality, defines what is just 6666. While I identify this as a circular argument that makes justice arbitrary, his response is laudably complete within its own presuppositions and directly relevant to the philosophical underpinnings of the debate. His calm tone makes for a productive exchange.

Charlie Brown

Scores: Completeness: 3, Relevance: 4, Civility: 4

Charlie’s primary method is quoting scripture without providing a logical bridge to answer the specific challenge of proportionality 7777. His responses are topically relevant but incomplete as a defense, functioning more as assertions of doctrine than explanations of it. His civility degrades over the conversation, culminating in a dismissive accusation of me using an LLM, which is an ad hominem fallacy meant to discredit the argument by attacking the arguer8.

Nick Mudge

Scores: Completeness: 1, Relevance: 2, Civility: 1

Nick’s responses are devoid of logical substance, consisting of hostile appeals to authority and insults, such as calling my logic “puny” and my efforts arrogant9999. He quotes scripture not to explain but to shut down inquiry, claiming the cross is “foolishness” to outsiders, thereby committing an ad hominem fallacy by labeling dissent as spiritual deficiency10. His approach is a prime example of hostile fideism and fails on all metrics of a reasoned or civil exchange.

Bill Breslin

Scores: Completeness: 1, Relevance: 5, Civility: 6

Bill’s contribution is a single, undeveloped assertion that my argument commits a category error by treating a qualitative issue (sin) quantitatively11. While the distinction between quality and quantity is potentially relevant, his failure to elaborate or defend this claim leaves his argument entirely incomplete. It is a drive-by assertion, not a developed thought.

Michael P Peppers

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 8

Michael’s response is a simple statement of faith—that I will eventually have to take my issue up with God—and he honestly admits it is not a logical argument12121212. While irrelevant to the logical critique, his candor and civility are commendable. He doesn’t pretend his faith-based assertion is a logical refutation, which is intellectually honest.

Roberta Jackson

Scores: Completeness: 7, Relevance: 9, Civility: 9

Roberta provides one of the most relevant and thoughtful engagements by challenging a key premise of my argument: that the penalty for sin is eternal conscious torment13131313. She proposes a model based on reconciliation and physical death which, while raising its own set of questions, demonstrates a willingness to critically engage with the theology rather than merely assert it. Her approach is a model of civil and substantive dialogue.

Scott Kurowicki

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 5

Scott’s comments are a mixture of undeveloped assertions, appealing to grace, mercy, and prophecy without connecting them to the core logical problem14141414. His claim that one “can’t put a measure on Jesus or God” is an attempt to dismiss the critique without addressing it15. The tone is somewhat dismissive, making for an incomplete and only tangentially relevant contribution.

John Washburn

Scores: Completeness: 1, Relevance: 2, Civility: 7

John’s response is a straightforward appeal to emotion and fear of consequence, stating he accepts the sacrifice because the alternative—eternal separation—seems illogical to risk16161616. This is an example of Pascal’s Wager and completely sidesteps the question of whether the doctrine is logically coherent. His argument is about pragmatic belief, not the internal consistency of the atonement model.

Steve Ernst

Scores: Completeness: 5, Relevance: 7, Civility: 8

After an initial dismissal, Steve engages more directly by arguing from divine fiat: “Justice means exactly what God says it means”17. He also attempts to tackle the value-vs-duration issue by asserting God’s non-equivalence with creation18. While this argument ultimately defines justice as arbitrary power, it is a relevant and moderately complete defense of that specific theological position.

Tim Sells

Scores: Completeness: 3, Relevance: 4, Civility: 5

Tim attempts to use a flawed analogy about subjective value (apples and pears) to explain the atonement, but this fails because justice requires objective proportionality, not subjective preference 19. He then retreats into fideism, claiming the “carnal mind cannot see the spiritual” and that clarity is not the objective, which is a method of insulating the belief from rational critique20202020.

Doug Nagel

Scores: Completeness: 4, Relevance: 7, Civility: 9

Doug clearly articulates the standard apologetic that Jesus’s “infinite value” makes the duration of his suffering irrelevant, allowing him to absorb infinite wrath in a finite time21. Although he doesn’t defend this position from my critique that it’s a category error, his response is civil, relevant, and a concise summary of a key Christian argument on this topic.

Owen Ashley

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 4, Civility: 8

Owen’s argument is an appeal to emotion, suggesting Jesus’s three-day separation “must have been like an eternity”22222222. This is a subjective interpretation that attempts to qualitatively inflate the suffering but does not address the objective, quantitative disparity between a finite event and an infinite penalty. It’s a poetic defense, not a logical one.

Andrew Sills

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 3

Andrew’s defense rests entirely on the concept of God’s sovereignty, which he uses as a shield to deflect any logical scrutiny23232323. He explicitly refuses to engage on logical terms and becomes condescending when pressed, suggesting my critique is an attempt to limit God24. This is an evasive and uncivil approach that shuts down dialogue by declaring his position immune to reason.

Terry Gurley

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 8

Terry shifts the discussion from the logic of the atonement to the prerogative of the creator, asking if God can be “in error” about His creation25. This is a straw man fallacy, as my critique is not about God’s rights but about the coherence of a specific doctrine of justice. His response is civil but irrelevant to the logical problem at hand.

Steve Bagnall

Scores: Completeness: 3, Relevance: 5, Civility: 8

Steve is commendably honest in his response, openly admitting that the atonement is “a non negotiable, no matter how illogical it might be” 26. While this doesn’t constitute a logical defense, his acknowledgment of the logical problem is a rare moment of candor. His argument is a complete defense of fideism, but an incomplete defense of a rational doctrine of justice.

Brian Baxter

Scores: Completeness: 8, Relevance: 9, Civility: 7

Brian provides the most structured and complete apologetic defense, addressing points on infinite worth, the nature of justice, and the role of the resurrection in a systematic way 27. While I still find his arguments—such as that value transcends time—to be category errors and his claims about justice to be special pleading, his response is highly relevant and demonstrates a comprehensive engagement with the critique. His initial tone was dismissive, but he moved to a more substantive argument.

Erik Weaver

Scores: Completeness: 6, Relevance: 7, Civility: 8

Erik presents a complex dispensationalist framework, distinguishing between remission and redemption and focusing on the blood rather than the duration of death 28282828. While his system is internally elaborate, it ultimately just relocates the proportionality problem without solving it: how a finite amount of “divine blood” pays an infinite debt remains unexplained. His response is relevant in that it offers an alternative theological model to critique.

Joshua Steindl

Scores: Completeness: 3, Relevance: 5, Civility: 8

Joshua argues that I am improperly forcing a theological concept into a “math equation” and rests his case on divine fiat: “If the God of the universe… says it’s enough, then it is good enough” 29. This is a relevant rebuttal to the method of my critique, but it’s an incomplete defense of the doctrine itself, as it simply asserts the conclusion.

Adam Bearly

Scores: Completeness: 3, Relevance: 4, Civility: 4

Adam proposes a highly creative and speculative solution involving God using extra time dimensions to create infinite, parallel suffering timelines for Jesus30. This is essentially an ad hoc rescue device, inventing new metaphysics to solve a theological problem, and has no basis in Christian scripture or theology. His response becomes sarcastic and dismissive when his novel theory is logically deconstructed31.

Fred Abbot

Scores: Completeness: 1, Relevance: 4, Civility: 7

Fred offers a single-sentence analogy: “One day of the eating of the fruit… was enough to damn the whole world”32. While this creates a parallel, it doesn’t function as an explanation and simply assumes a disproportionate relationship between act and consequence, which is the very thing being questioned.

Carolyn Szalkowski Brewster

Scores: Completeness: 4, Relevance: 6, Civility: 4

Carolyn makes the relevant point that the three-day duration may have been for evidentiary purposes to prove the reality of the death, not as part of the payment itself 33. However, this doesn’t solve the core problem of how the death—regardless of its confirmed duration—satisfies an infinite penalty. Her tone is condescending, suggesting I should do “basic research” instead of posing “ludicrous notions”34.

Mike Grygus

Scores: Completeness: 4, Relevance: 6, Civility: 8

Mike offers a thoughtful and novel suggestion that an “infinite amount of punishment” might be required to kill a God-man, thus satisfying the debt in the act of dying itself35. This is a creative attempt to build a coherent mechanism, but it remains a speculative assertion without theological backing and reverses the normal understanding of punishment and endurance.

Dougyarb Duane

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 3, Civility: 6

Dougyarb argues from a position of Calvinistic predeterminism, stating that no price was ever to be paid for the eternally damned, as they were never in the book of life 36. This sidesteps the question entirely by changing the subject from how the atonement works for the saved to who it does not apply to.

Bryant Coots

Scores: Completeness: 4, Relevance: 6, Civility: 10

Bryant’s response is one of the most humble and philosophically open, acknowledging the tension between logic and faith and affirming that God should not be threatened by honest inquiry37373737. He doesn’t offer a complete defense of the doctrine but instead provides a model for civil, productive dialogue, earning a perfect score for civility.

John Soulliere

Scores: Completeness: 8, Relevance: 8, Civility: 8

John doesn’t respond to me directly but makes a highly relevant and theologically astute correction to Wayne Clarke’s argument about divine separation38. He points out that Jesus’s cry was a quote from Psalm 22, a psalm that ends in victory, not a literal statement about the Trinity fracturing39. This is a complete and cogent point that refines the terms of the internal Christian debate.

Mike McKinney

Scores: Completeness: 5, Relevance: 7, Civility: 5

Like John, Mike engages another Christian (Wayne Clarke), labeling his “spiritual death” view as heresy404040. His correction is relevant and theologically important within the orthodox framework, but his tone is sharp and accusatory. The use of terms like “heresy” and “ignorance” lowers his civility score compared to other corrective comments41.

Michael Kirkwood

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 4, Civility: 9

Michael is admirably humble and honest, admitting he cannot logically explain the atonement and can only “rest in what God’s Word says”42. His response is incomplete as a defense but demonstrates high civility and intellectual integrity by not pretending to have an answer where he sees only mystery.

Lance T. Marshall

Scores: Completeness: 4, Relevance: 5, Civility: 7

Lance attempts several different lines of attack, questioning the premise of proportionality and citing scripture about time’s relativity to God, which misapplies the verse’s context 43. His arguments are scattered and don’t form a single coherent rebuttal. The appeal to Einstein’s subjective experience of time is another category error, confusing subjective feeling with objective duration44.

Zachary Reitsma

Scores: Completeness: 2, Relevance: 6, Civility: 8

Zachary makes the direct and relevant claim that the duration of death is “irrelevant” and only the sacrifice itself matters 45. This is an incomplete argument because it makes the three-day timeline theologically arbitrary and still fails to explain how the sacrifice itself, as a finite event, provides a proportional payment for an infinite debt.

| Interlocutor | Completeness | Relevance | Civility | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberta Jackson | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8.3 |

| Andrew Bartlett | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8.0 |

| Brian Baxter | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8.0 |

| John Soulliere | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8.0 |

| Benjamin Andersen | 5 | 7 | 9 | 7.0 |

| Erik Weaver | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7.0 |

| Leif Egil Reve | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7.0 |

| Bryant Coots | 4 | 6 | 10 | 6.7 |

| Doug Nagel | 4 | 7 | 9 | 6.7 |

| Steve Ernst | 5 | 7 | 8 | 6.7 |

| Mike Grygus | 4 | 6 | 8 | 6.0 |

| Mike McKinney | 5 | 7 | 5 | 5.7 |

| Joshua Steindl | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Lance T. Marshall | 4 | 5 | 7 | 5.3 |

| Steve Bagnall | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Zachary Reitsma | 2 | 6 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Michael Kirkwood | 2 | 4 | 9 | 5.0 |

| Carolyn Brewster | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4.7 |

| Owen Ashley | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4.7 |

| David J Wireback Jr. | 2 | 4 | 7 | 4.3 |

| Michael P Peppers | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4.3 |

| Terry Gurley | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4.3 |

| Bill Breslin | 1 | 5 | 6 | 4.0 |

| Fred Abbot | 1 | 4 | 7 | 4.0 |

| Tim Sells | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4.0 |

| Adam Bearly | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.7 |

| Charlie Brown | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3.7 |

| Dougyarb Duane | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3.7 |

| John Washburn | 1 | 2 | 7 | 3.3 |

| Scott Kurowicki | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3.3 |

| Bill Elgin | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3.0 |

| Andrew Sills | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 |

| Wayne Clarke | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Nick Mudge | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.3 |

Commentary:

Based on the provided dialogue and analysis, the Christian interlocutors’ defense of Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA) is undermined by a series of recurring logical blunders and argumentative shortcomings. Rather than presenting a coherent, falsifiable model of divine justice, their arguments consistently rely on category errors, appeals to arbitrary authority, and evasive fallacies. This essay will highlight the four most prominent failures in their reasoning: the conflation of qualitative worth with quantitative duration, the reduction of justice to divine fiat, the unaddressed contradiction of a finite payment for an infinite penalty, and the retreat into non-argumentative tactics when logical inconsistencies are exposed.

The Fundamental Category Error: Infinite Worth vs. Infinite Duration

At the core of the apologists’ defense is the assertion that Jesus’s infinite worth or divine nature makes his finite suffering sufficient to satisfy an infinite penalty. Interlocutors from Andrew Bartlett to Brian Baxter lean heavily on this concept, arguing that the quality of the substitute matters more than the quantity of time served. However, as Phil’s critique demonstrates, this is a fundamental category error. Assigning infinite worth to a finite event does not mathematically or logically convert a finite quantity into an infinite one. There is no coherent metric or mechanism offered to explain how value translates into temporal duration.

This blunder is vividly illustrated in the Solara analogy, where Judge Marshall declares his son Ethan’s three-day stay in a comfortable suite is sufficient to cancel a million life sentences simply because of Ethan’s “infinite worth” as the heir. Just as one cannot settle a billion-dollar debt with three dollars, the interlocutors cannot logically satisfy an eternal penalty with a three-day death without inventing untestable dynamics that have no parallel in rational systems of justice.

The Appeal to Divine Fiat: Justice as an Arbitrary Decree

When pressed on the logical mechanics of the atonement, a majority of the interlocutors retreat to divine fiat, arguing that the substitution is just simply because God, in His sovereignty, declares it so. This position, articulated by figures like Steve Ernst and Andrew Sills, sidesteps the problem by making justice an arbitrary and unfalsifiable concept. If justice is merely whatever God decrees, then the term itself becomes a tautology: “God is just” means only that God does what He wants, and what He wants is labeled “just.”

This creates a circular moral economy, a “closed loop” where the offended party (God) is also the lawgiver, the provider of the substitute, and the ultimate validator of the transaction, with no external accountability. This framework mirrors the absurd, self-contained logic of Alice in Wonderland, where the Queen of Hearts’ decrees are law without any need for rational justification. By grounding justice in an unchallengeable decree, the interlocutors defend a system that is coherent only to its adherents and appears capricious to any outside observer applying consistent logical standards.

The Unaddressed Reductio: Proportionality and the Resurrection

A coherent system of justice demands that penalties be proportionate to the offense. Throughout the debate, the interlocutors consistently fail to demonstrate how a brief, temporary death is in any way proportional to an eternal, unending punishment. This failure is most starkly revealed in the unaddressed reductio ad absurdum of the resurrection: if the required penalty for sin is eternal death or separation from God, then Jesus’s resurrection after a finite period proves he did not pay that penalty in full. An escape from an eternal sentence is not the same as serving it.

While some interlocutors mention the resurrection, they frame it as a sign of victory or proof that the payment was accepted, but they never resolve the logical contradiction it introduces for a substitutionary model. They fail to explain how a penalty can be both eternal and temporary. This glaring inconsistency remains the central, unanswered challenge that dismantles the claim of a proportional substitution.

Evasion through Mystery and Ad Hominem Fallacies

Finally, when confronted with these logical and proportional shortfalls, many interlocutors abandon reasoned argumentation in favor of evasive tactics. The first is the appeal to mystery, where figures like David J. Wireback Jr. and Michael Kirkwood claim that God’s ways are beyond human comprehension. This tactic does not resolve the logical problem but merely insulates the doctrine from scrutiny, effectively conceding that it is not rationally coherent.

The second, more egregious, tactic is the use of ad hominem attacks. Interlocutors like Wayne Clarke and Nick Mudge, unable to defend the doctrine on logical grounds, resort to questioning Phil’s motives, character, and spiritual state, accusing him of arrogance or doing “Satan’s work.” This well-documented fallacy is a clear sign of a weak argumentative position, as it attempts to discredit the questioner to avoid engaging with the substance of the critique itself.

Conclusion

The defenses of Penal Substitutionary Atonement offered by the interlocutors are fraught with consistent and fundamental logical blunders. They rely on a central category error by conflating worth with duration, retreat to an arbitrary system of divine fiat that renders justice meaningless, fail to address the fatal contradiction that the resurrection introduces, and ultimately fall back on logical fallacies to evade scrutiny. Their arguments depend on “invented dynamics” and a “theological Wonderland” that is coherent only by its own internal, untestable rules. For the doctrine to be considered rationally defensible, it requires a foundation of logical consistency and falsifiable reasoning, elements conspicuously absent from the interlocutors’ remarks.

Formalizations of the Arguments & Counterarguments

This essay formalizes the central arguments presented in the Facebook group discussion on Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA). It will first construct the primary formulations used by the interlocutors to defend PSA, primarily focusing on the concepts of infinite worth and divine fiat. Subsequently, it will present counter-formulations that demonstrate the logical incoherence and category errors inherent in these defenses, based on the critiques found within the provided source materials.

Argument 1: The Apologetic Formulation from Infinite Worth

The most common defense of PSA among the interlocutors is the claim that Jesus’s divine nature provides his finite suffering with infinite value, thereby satisfying an eternal penalty. This argument can be formalized by defining a set of predicates and constructing a logical sequence.

Let the following predicates be defined:

: x is a sinner.

: x deserves an eternal penalty,

.

: Jesus (j) serves as a substitute to atone for sinner x.

: Jesus suffers for a finite duration, providing satisfaction

.

: Jesus possesses infinite worth.

: Penalty p is justly satisfied by act q.

The apologetic argument proceeds as follows:

- All sinners deserve an eternal penalty.

- Jesus, as a substitute, suffers for a finite duration.

- The central premise: If Jesus possesses infinite worth, his finite suffering is sufficient to satisfy the eternal penalty.

- Jesus possesses infinite worth.

C: Therefore, by Modus Ponens on (3) and (4), Jesus’s finite suffering satisfies the eternal penalty.

The Counter-Formulation: Exposing the Category Error and Contradiction

The critique of the above formulation reveals that the bridge premise in step (3) is an unsubstantiated assertion that commits a category error. To demonstrate this, we must introduce predicates that distinguish between qualitative attributes and quantitative measures.

Let the following be defined:

: The quantitative duration of a penalty or act p.

: The value for infinite duration.

: A specific finite time value.

The critique can now be formalized:

- A core principle of commensurate justice is that for a substitution to be equivalent, the duration of the act must match the duration of the penalty.

- The penalty for sin has an infinite duration.

- Jesus’s suffering had a finite duration.

- The apologist concludes that the satisfaction is equivalent to the penalty,

.

Applying the principle of justice from (1) to the apologist’s conclusion in (4), we derive by Modus Ponens:

C1:

Substituting the known values from (2) and (3), we arrive at a contradiction:

C2:

This contradiction demonstrates that the apologists’ framework is internally incoherent. The predicate (infinite worth) is a qualitative attribute that has no valid logical operator connecting it to the quantitative claim that an infinite duration is equal to a finite one. The premise

is thus exposed as a non-sequitur, fallaciously bridging two distinct logical categories.

Argument 2: The Apologetic Formulation from Divine Fiat

A second common defense is the appeal to God’s sovereignty, where justice is defined as whatever God declares it to be.

Let the following predicates be defined:

: God.

: God declares that act q satisfies penalty p.

: Penalty p is justly satisfied by act q.

The apologetic argument from divine fiat is:

- The primary premise: An act is a just satisfaction if and only if God declares it so. This makes justice synonymous with divine decree.

- God declares that Jesus’s finite suffering satisfies the eternal penalty.

C: Therefore, by Biconditional Elimination on (1) and (2), Jesus’s finite suffering justly satisfies the eternal penalty.

The Counter-Formulation: Exposing the Tautology

The critique of this formulation is that it does not provide a model of justice but rather a tautology that renders the concept of justice meaningless and arbitrary.

- The apologist’s core premise,

, defines justice not by principles like proportionality or equivalence, but solely by divine will.

- Let

be the proposition “Act ‘a’ is just.” The argument effectively states

, where

means “God declares PSA to be just.”

- This formulation is a circular definition. It fails to provide any independent criteria for justice, instead creating a closed logical loop where the validator of the system is internal to the system itself. It does not prove that PSA is just; it merely asserts that whatever God does is labeled “just,” which is an unfalsifiable and trivial claim.

Argument 3: The Reductio ad Absurdum of the Resurrection

The doctrine of the resurrection, when combined with the premises of PSA, creates a formal contradiction, demonstrating the system’s internal incoherence.

Let the following predicates be defined:

: Substitute s fully bears penalty p.

: Jesus was resurrected.

The reductio ad absurdum proceeds as follows:

- Premise from PSA: For a substitute to atone for a sinner, the substitute must fully bear the sinner’s penalty.

- Premise from PSA: The penalty for sin is eternal in duration.

- Premise from logic: To fully bear a penalty of eternal duration, the substitute’s suffering must also be of eternal duration.

- Premise from Christian doctrine: Jesus was resurrected.

- Premise from logic: Resurrection implies that the suffering was not of eternal duration.

From these premises, we can derive a contradiction:

- From (4) and (5) by Modus Ponens, we conclude that Jesus’s suffering was not eternal.

- From (6) and (3) by Modus Tollens, we conclude that Jesus did not fully bear the eternal penalty.

C: From (7) and (1) by Modus Tollens, we conclude that Jesus did not atone for the sinner.

This result contradicts the foundational Christian claim that Jesus’s act was atoning. Therefore, the set of premises held by the interlocutors—that the penalty is eternal, that the substitute must fully bear it, and that Jesus was resurrected—is logically inconsistent.

Conclusion

When formalized, the primary arguments defending Penal Substitutionary Atonement demonstrate a reliance on logically invalid steps. The argument from “infinite worth” commits a category error, fallaciously equating a qualitative attribute with a quantitative measure of duration. The argument from “divine fiat” is not a defense of justice but a tautological claim that renders the concept of justice arbitrary and unfalsifiable. Finally, the doctrine’s core tenets are shown to be mutually contradictory when analyzed through the reductio ad absurdum of the resurrection. For PSA to be considered logically coherent, its defenders must provide a valid formulation that resolves these formal contradictions without resorting to non-sequiturs or circular reasoning.

◉ Misguided Tactics

An analysis of the theological debate surrounding Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA) reveals a distinct pattern of argumentation among its defenders. When confronted with the central logical challenge—how a finite, temporary death can justly satisfy an infinite, eternal penalty—many interlocutors in the provided discussion eschew direct logical resolution. Instead, they consistently employ a set of rhetorical tactics and logical fallacies designed to sidestep, dismiss, or delegitimize the critique itself. These argumentative maneuvers, while perhaps effective in reinforcing belief within a faith community, fail to provide a rational defense of the doctrine. A rigorous examination of these tactics—the appeal to divine authority, the appeal to mystery, ad hominem attacks, and the shifting of the burden of proof—exposes a profound weakness in the logical foundation of the apologetic for PSA.

The most prevalent tactic is the appeal to divine authority, also known as divine fiat. This move attempts to resolve the logical problem of proportionality by dissolving the very concept of objective justice, making it entirely subject to God’s decree. Interlocutors like Benjamin Roald Andersen and Steve Ernst exemplify this approach, with the latter stating bluntly, “Justice means exactly what God says it means.” This argument posits that because God is the ultimate author of morality and logic, His actions define what is just by their very nature. However, this is not a defense of justice but a tautology. It creates a closed, circular system where the statement “God is just” becomes meaningless, translating only to “God does what God wills.” By defining justice as synonymous with divine power, this argument removes any independent, intelligible standard by which God’s actions could be evaluated. Consequently, the core critique is not answered; it is declared irrelevant by an arbitrary redefinition of terms, reducing justice from a coherent principle to an expression of raw, unaccountable authority.

When the appeal to authority proves insufficient, defenders frequently pivot to an appeal to mystery. This tactic functions as an intellectual retreat, shielding the doctrine from scrutiny by claiming it operates beyond the limits of human reason. David J. Wireback Jr. invokes scripture to claim the “natural mind cannot comprehend things of God,” while Steve Bagnall concedes, “our earthly logic can’t even begin to comprehend the size & power of God.” While faith traditions often contain elements of mystery, invoking it to neutralize a specific, demonstrable logical contradiction is an abdication of reasoned discourse. It is an implicit admission that the doctrine, when analyzed on logical terms, is incoherent. This move renders the claim of a just substitution unfalsifiable, as any logical inconsistency can be conveniently placed in the category of the unknowable. Instead of resolving the tension between a finite act and an infinite penalty, the appeal to mystery simply declares the tension off-limits to rational inquiry.

Should these attempts to reframe the debate fail, a more aggressive and fallacious tactic emerges: the ad hominem attack. Rather than addressing the substance of the logical critique, several interlocutors shift their focus to the character, motives, or methods of the questioner. Wayne Clarke’s accusation that the critic is wearing the work of “Satan” well, or Nick Mudge’s dismissal of the argument as the product of a “simple AI driven troll,” are prime examples of this fallacy. Such attacks are logically irrelevant, as the validity of an argument is independent of the person making it. The use of ad hominem is a clear indicator of a weak argumentative position, as it seeks to poison the well and discredit the messenger when the message itself proves difficult to refute. This rhetorical maneuver serves not to defend the doctrine, but to shut down the conversation by intimidating or delegitimizing the source of the critique.

Finally, a more subtle but equally flawed tactic is shifting the burden of proof. The responsibility for providing evidence for a claim lies with the person making that claim. In this debate, the positive claim is that Penal Substitutionary Atonement is a just and coherent system. Yet, interlocutors like Andrew Sills attempt to invert this epistemic responsibility, demanding, “YOU have to show how God is limited to your logic and and math.” This misframes the critique. The challenge is not an attempt to place external limits on God; rather, it is a request for the defenders of PSA to provide a coherent justification for the specific claims they are making about God and justice. By demanding that the skeptic disprove a negative or prove that God must adhere to human logic, the apologist evades their fundamental obligation to substantiate their own position, effectively arguing that their claim should be accepted as true until proven otherwise.

In conclusion, the pattern of responses from the defenders of Penal Substitutionary Atonement demonstrates a consistent avoidance of the central logical problem. The reliance on divine fiat, appeals to mystery, ad hominem attacks, and the shifting of the burden of proof are not arguments that resolve the incoherence of a finite act satisfying an infinite penalty. They are evasive strategies that reveal a doctrine unable to withstand rigorous logical scrutiny on its own terms. A theological system that claims to be rooted in ultimate truth and justice should be defensible through reason and coherence, not shielded by fallacies and rhetorical deflections. The prevalence of these tactics suggests that, when pressed, the popular defense of PSA rests less on logical integrity and more on the assertion of authority and the insulation of belief from critical inquiry.

The Recognition of the Christian Tactics from the Perspective of an Ex-Muslim

(Fictive, but Accurate)

Reading through this debate was a deeply familiar experience. The argumentative patterns and rhetorical tactics employed by the Christian interlocutors in defense of their doctrine are the very same ones I once used with conviction to defend the tenets of Islam. This shared methodology reveals a crucial insight: these tactics are not unique proofs of any particular faith, but are generic, content-neutral fallacies that serve to insulate belief from scrutiny rather than demonstrate its rational coherence. From my current perspective, I see clearly how these arguments, which once felt like a fortress, are in fact a facade, protecting not truth, but the believer from the discomfort of logical inquiry.

The most common tactic is the appeal to divine authority, and I know it well. When Christian interlocutors like Steve Ernst claim, “Justice means exactly what God says it means“, I hear an echo of my former self. I used to make the exact same argument for Islam, insisting that justice is precisely what Allah (SWT) has decreed in the Qur’an, for He is Al-Hakam (The Judge), the ultimate source of law. I argued that His will was the standard against which all else is measured. I eventually realized, however, that I was not defending a just God, but simply a powerful one. This argument makes justice arbitrary and tautological; it becomes a label applied to raw power. It fails to persuade any outsider because it proves nothing beyond asserting the supremacy of one’s chosen authority, a move available to any and every religion.

When pressed on a logical contradiction, the next line of defense is inevitably the appeal to mystery. I see this in the words of David J. Wireback Jr., who states the “natural mind cannot comprehend things of God“. This was my go-to response for any challenging question in Islam, from the problem of predestination (Qadr) to the eternal nature of the Qur’an. I would appeal to the concept of Ghaib (the unseen), arguing that Allah’s wisdom is beyond our finite grasp. But I came to see this not as an act of pious humility, but as an intellectual retreat. It is an admission that a doctrine cannot be logically reconciled. Invoking mystery is a conversation-stopper, not an answer, and it works equally well for any religion with an incomprehensible deity, rendering it useless as a tool for discerning truth.

Should these defenses fail, the debate often degrades into ad hominem attacks, a tactic that is painfully familiar. Seeing Wayne Clarke accuse the critic of wearing the work of “Satan” well or Nick Mudge dismiss him as a “troll” brought back memories of discussions where I, or those around me, would dismiss critics of Islam by questioning their sincerity, accusing them of being influenced by Shaitan, or labeling them as kuffar whose hearts were sealed against the truth. This is the easiest way to feel victorious in a debate you are losing on its merits. I now see it for what it is: a defense mechanism that protects the believer’s ego but does nothing to prove their point. It is a universal sign that the argument has been lost and all that remains is personal attack.

Finally, there is the subtle but potent fallacy of shifting the burden of proof. When Andrew Sills demands of the critic, “YOU have to show how God is limited to your logic and and math“, I recognize the move immediately. I used to challenge critics of Islamic law by saying, “You must first prove that Allah is bound by your secular, Western standards of reason.” This tactic wrongly places the epistemic burden on the questioner. The person making the positive claim—that Penal Substitution is a coherent model of justice, or that Islam is the one true faith—is the one responsible for substantiating it. Demanding that the critic disprove an unfalsifiable negative is an admission that you cannot prove your own positive claim. It is a rhetorical trick to evade the responsibility of providing evidence.

In conclusion, the apologetic strategies on display in this debate are not unique to Christianity but are part of a universal playbook for defending faith against reason. Having once used this playbook myself, I see that these tactics—appeals to absolute authority, inscrutable mystery, personal attacks, and burden-shifting—are interchangeable props that can be wielded in service of any dogma. The Christian interlocutors, in resorting to them, fail to offer a compelling case for their doctrine. Instead, they unwittingly demonstrate that their methods of defense are generic, logically flawed, and ultimately empty of the very evidential force that a claim to ultimate truth requires.

See also:

Leave a comment