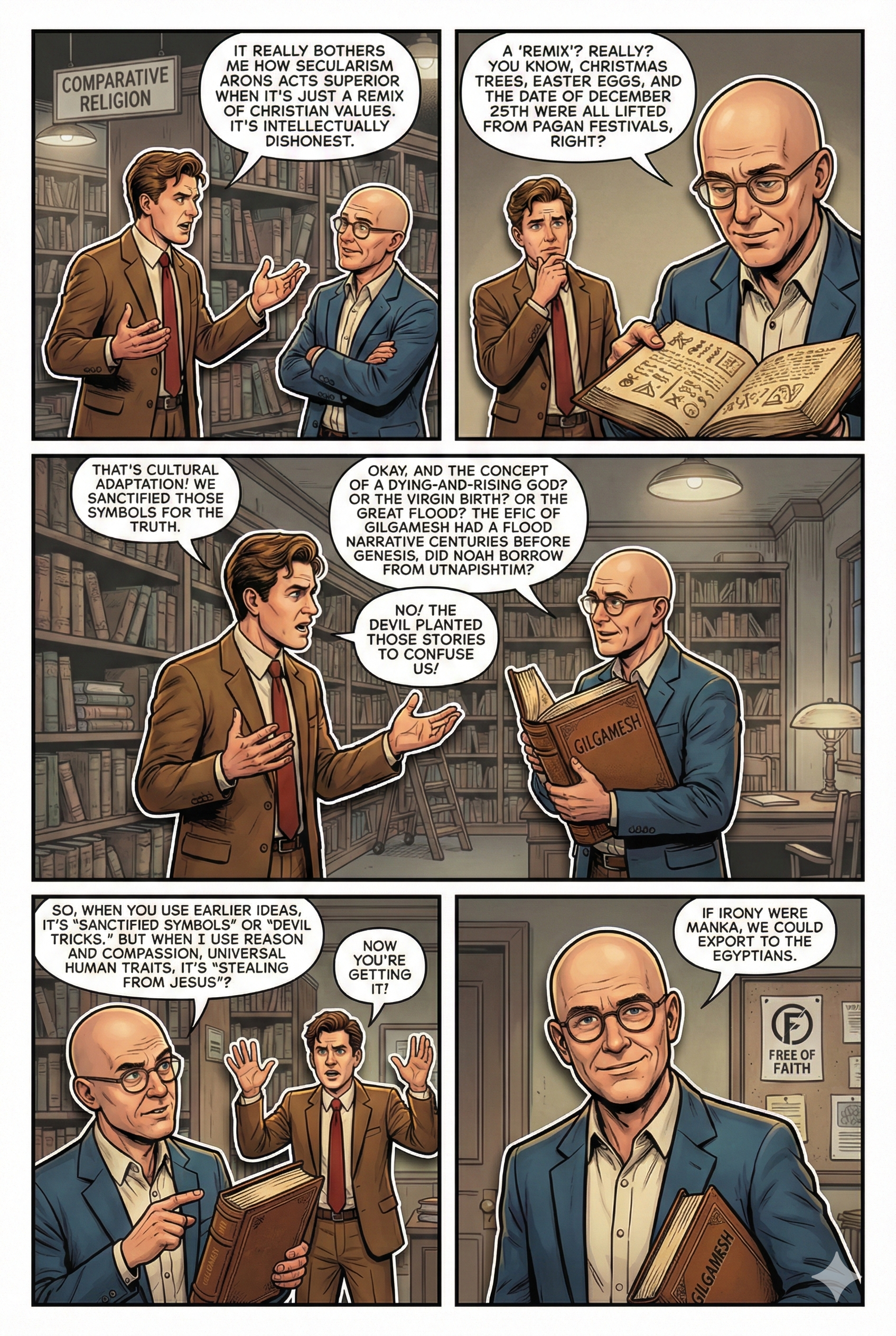

This collection of arguments critically examines the common claim made by Christian apologists that secular systems “borrow” essential concepts—such as morality, justice, free will, and human dignity—from the Christian worldview. The essays delve into the motivations behind this claim, which include portraying Christianity as the indispensable source of truth while framing secular worldviews as ideologically inferior or incoherent. By addressing these claims through historical evidence, philosophical critique, and symbolic logic, the discussions demonstrate that such arguments often oversimplify the origins of universal human values. Concepts like love, compassion, and justice are shown to have emerged across diverse cultures, predating Christianity and existing independently of its theological framework.

The essays below will also reveal the self-defeating nature of the borrowing argument. If borrowing renders a worldview inferior, then Christianity itself—built on ideas borrowed from Judaism, Stoicism, and Greek philosophy—would fail by the same standard. Through formal logical analysis, contradictions in the apologists’ reasoning are exposed, demonstrating that the claim lacks consistency and validity. Rather than dismissing borrowing as a flaw, the essays argue that it reflects the collaborative and evolving nature of human thought. Readers are invited to explore how the universality of values and the shared heritage of ideas enrich our understanding of morality, justice, and human purpose, providing a foundation for more constructive and inclusive dialogue.

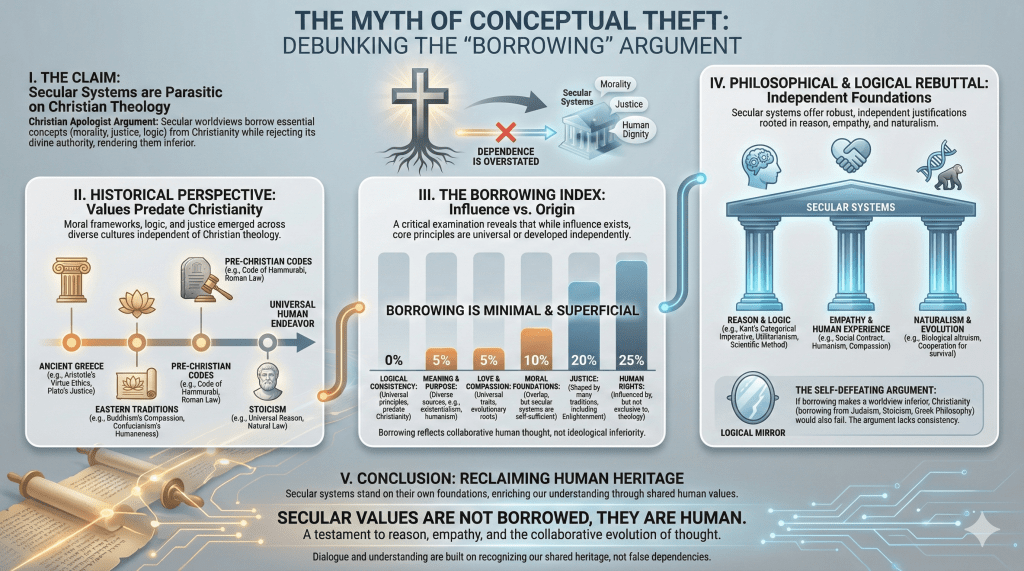

Borrowing Percentages and Commentary

| Category |  | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Moral Foundations | 10% | Secular morality shares some historical overlap with Christian teachings. |

| Logical Consistency | 0% | Logical principles predate Christianity and are universal in application. |

| Meaning and Purpose | 5% | Christianity influenced Western ideas of purpose but is not the sole source. |

| Ethical Accountability | 15% | The concept of accountability is partly tied to Christian theological systems. |

| Justice | 20% | Christian doctrines shaped Western ideas of justice, though not exclusively. |

| Human Rights | 25% | Human rights language was heavily influenced by Christian theological ideas. |

| Meaning in Suffering | 10% | Christianity emphasizes redemptive suffering, shared in some secular ideas. |

| Love and Compassion | 5% | These are universal values found across cultures, not uniquely Christian. |

| Free Will | 5% | Free will has roots in earlier traditions and secular philosophical systems. |

| Gratitude | 5% | Gratitude is a universal human emotion, though expressed in theology. |

| Sense of Transcendence | 10% | Transcendence is often framed theologically but also exists in secular awe. |

- Those who disagree with the content of this table and the relevant arguments are strongly encouraged to provide counter-arguments in the comments section below.

01

Do Secular Moral Foundations Borrow from Christianity?

The claim that secular moral foundations borrow from Christianity is a recurring theme in Christian apologetics. This argument typically asserts that secular worldviews are parasitic on the moral teachings of Christianity, relying on its core values while rejecting its divine authority. However, this assertion does not hold up to scrutiny when examined through historical, philosophical, and logical lenses. Let us unpack the claim, counter it with reason, and delve into why secular moral foundations stand independently of Christianity.

A Historical Perspective: Morality Predates Christianity

To claim that morality stems exclusively from Christianity is to disregard the rich moral traditions that predate its emergence. Ancient Greek philosophy, for instance, offered comprehensive moral frameworks. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle debated justice, virtue, and the good life long before the advent of Christian theology. Similarly, Eastern philosophies such as Confucianism and Buddhism emphasized compassion, respect, and ethical living centuries earlier.

Even in pre-Christian pagan societies, moral codes governed communal life. The Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE) laid down principles of fairness and justice, illustrating that moral systems arose organically to maintain social cohesion. These examples demonstrate that morality is not an exclusive byproduct of Christianity but rather a universal human endeavor.

A Philosophical Perspective: Secular Moral Frameworks

Philosophers like Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, and John Rawls developed moral theories independent of Christian theology. Kant’s categorical imperative provides a rational basis for ethical behavior by appealing to universal principles, while Mill’s utilitarianism evaluates morality based on the consequences of actions and the promotion of happiness.

Such secular frameworks do not require divine intervention to justify moral behavior. Instead, they appeal to reason, empathy, and the intrinsic value of human relationships. Moreover, evolutionary biology provides compelling evidence that moral behaviors such as cooperation, fairness, and altruism evolved because they enhanced group survival. This naturalistic explanation renders the need for divine commandments unnecessary.

Logical Rebuttal: Independence of Secular Morality

The claim that secular morality borrows from Christianity can be rigorously dismantled using logical reasoning. Consider the following syllogism:

Premises:

(Moral systems can exist independently of Christianity and are therefore secular.)

(There are moral systems, such as those from Greek and Indian philosophies, that do not borrow from Christianity.)

Conclusion:

(Secular moral systems do not necessarily borrow from Christianity.)

This formulation demonstrates that secular morality does not rely on Christian teachings for its coherence or validity.

A Thought Experiment: The Atheist and the Samaritan

Imagine an atheist who helps a stranger in need. When asked why, they might reply, “Because it’s the right thing to do.” This instinct to assist stems from empathy and a shared sense of humanity, not from a belief in divine commandments. The Christian apologist might argue that the notion of “doing the right thing” is itself a borrowed Christian value. But is it?

If we strip the act of its cultural trappings, we find that altruism and cooperation are inherent to human nature. Studies in primatology reveal that even chimpanzees display rudimentary fairness and empathy. These behaviors suggest that morality is rooted in biology and social dynamics rather than theology.

The Borrowing Percentage: Minimal at Best

While it’s true that Christian teachings have shaped Western moral discourse, their influence on secular morality is superficial. Secular systems are largely self-sufficient, drawing from reason, experience, and shared human values. Borrowing is limited to linguistic or cultural expressions, not foundational principles.

Borrowing percentage: 10%.

Conclusion: Secular Morality Stands on Its Own

The notion that secular moral foundations borrow heavily from Christianity collapses under scrutiny. Historical evidence reveals that morality existed long before Christianity, and philosophical reasoning shows that secular systems can independently justify ethical behavior. Logical analysis confirms that borrowing is not a necessity but, at most, a cultural byproduct.

Secular morality, grounded in reason, empathy, and human experience, requires no divine scaffolding. It is a testament to humanity’s ability to navigate the complexities of life ethically and compassionately—on its own terms. Far from being parasitic, secular morality is an independent and vibrant moral ecosystem.

The editor of this site actually holds that secular morality also fails to establish any system of morality that does not, once scrutinized, dissipate into mere emotions and emotionally-derived values with no obligatory force. Articulate your disagreements in the comments section below if you are willing and ready for a deep dive into metaethics.

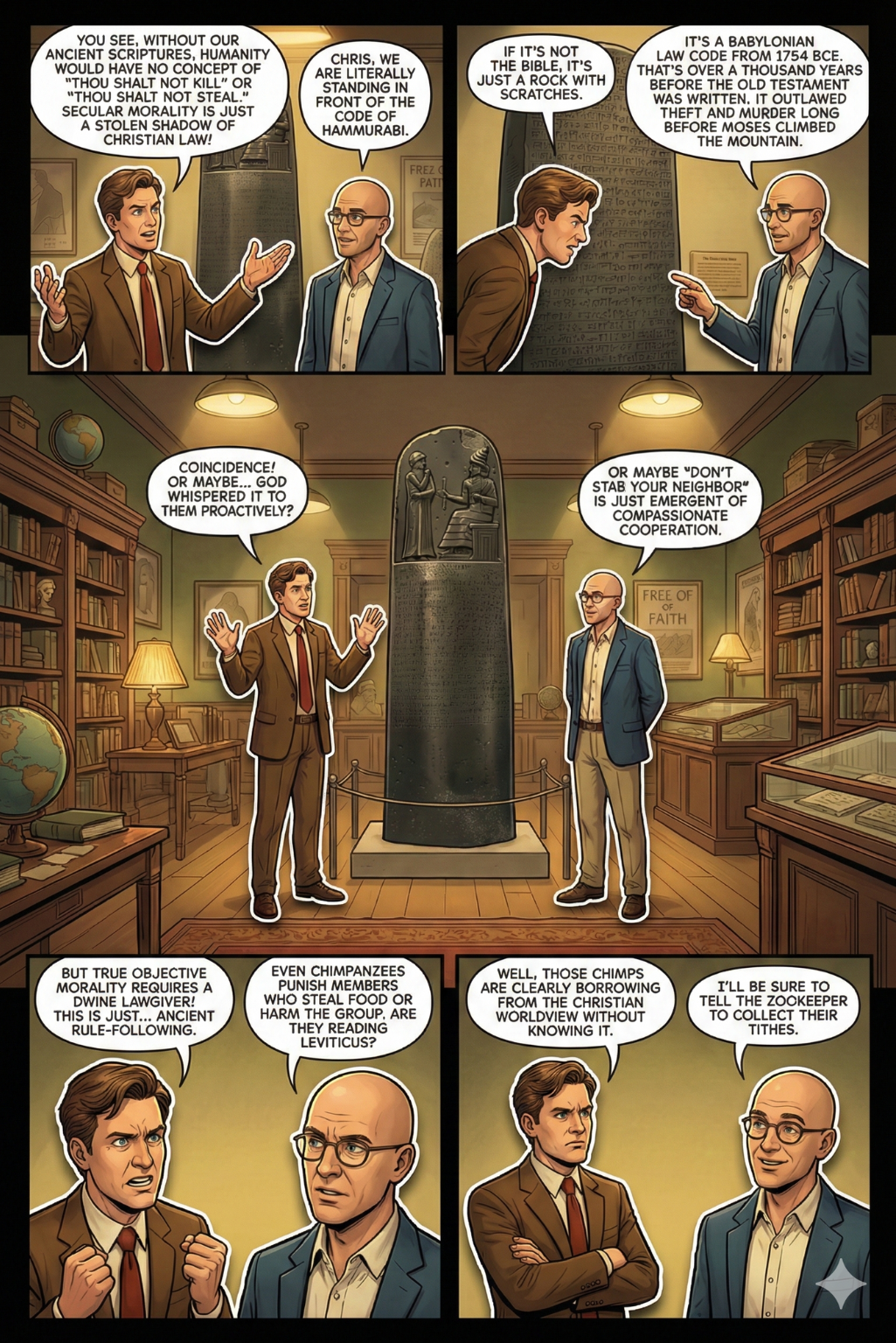

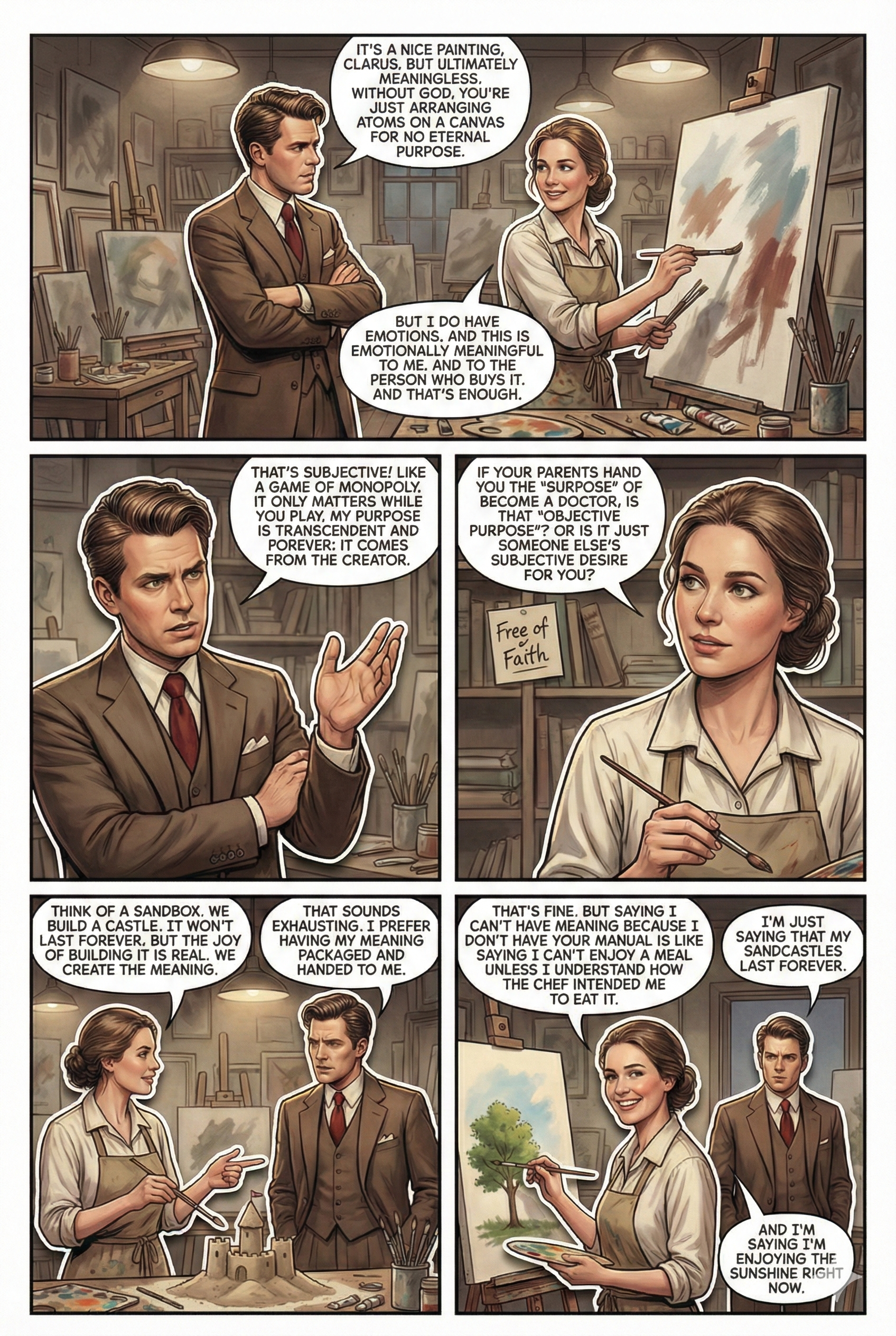

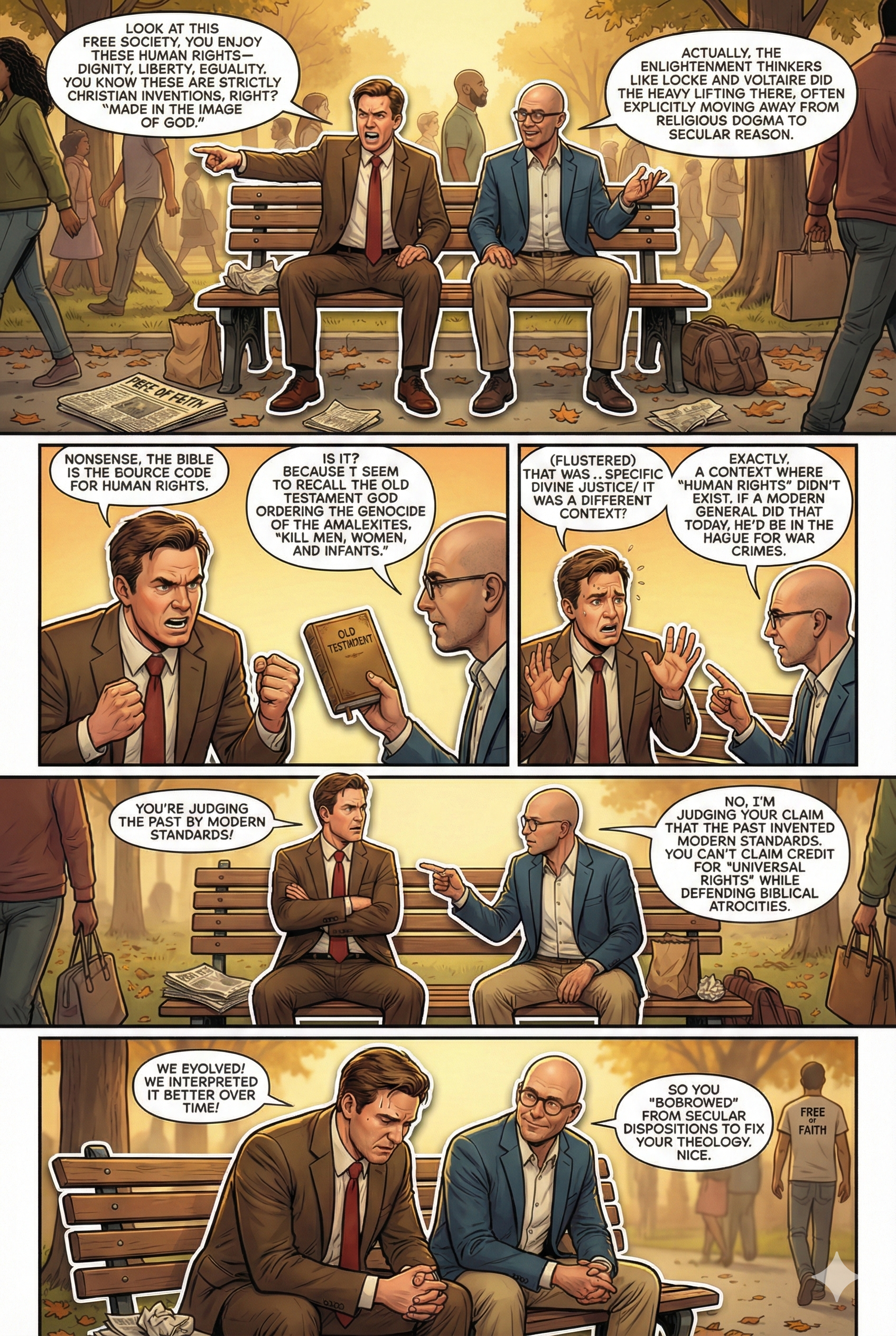

Dialogue

CHRIS: You secularists amuse me. You walk around with your talk of morality, justice, and compassion, but you’re really borrowing it all from Christianity. Without the moral foundations laid out by the Bible, your whole ethical framework would crumble.

CLARUS: That’s a bold claim, Chris, but one I’d challenge. I don’t deny that Christianity has influenced Western moral discourse, but to suggest that secular morality borrows from Christianity is both historically and philosophically flawed. Morality predates Christianity and can be grounded in natural, rational principles.

CHRIS: Oh, please. Morality predating Christianity? I’d like to see your evidence for that. Christianity introduced the concept of universal human dignity—rooted in humans being made in the image of God. That’s the foundation of everything you secularists cherish today.

CLARUS: Universal human dignity is indeed a valuable concept, but it is neither unique to Christianity nor its invention. Ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle and Plato discussed virtues, justice, and the good life long before the Bible came into play. Aristotle, for example, outlined a framework of ethics based on human flourishing (eudaimonia), achieved through cultivating virtues like courage, generosity, and fairness. This isn’t derived from theology but from observing human nature and relationships.

CHRIS: But those Greek ideas were elitist. Aristotle didn’t believe everyone had equal moral worth. Christianity is what brought the radical idea that all people, regardless of status, are equal in the eyes of God.

CLARUS: I concede that early Greek thought often reflected the hierarchical structures of their societies, but the idea of equality didn’t emerge solely from Christianity. Stoic philosophers, such as Seneca and Epictetus, argued that all humans share the capacity for reason and are part of a universal community. These principles are remarkably egalitarian and entirely secular. Moreover, many societies long before Christianity had moral codes emphasizing reciprocity and fairness, such as the Code of Hammurabi.

CHRIS: Codes of Hammurabi? Come on! Those were primitive laws designed to enforce order through fear, not a true moral framework. Christianity brought love and selflessness into the equation.

CLARUS: Love and selflessness weren’t invented by Christianity either. Buddhism, which predates Christianity by centuries, teaches karuṇā (compassion) and mettā (loving-kindness) as central virtues. Confucianism emphasizes ren (humaneness) and reciprocity as foundational to ethical living. These traditions demonstrate that love and selflessness are universal human values, not exclusive to Christianity.

CHRIS: Fine, let’s say these values existed in some form before Christianity. But what gives secular morality any authority? Without God as the ultimate source, how can you justify your moral claims? They’re just opinions, floating in the void.

CLARUS: On the contrary, morality doesn’t need a divine source to have authority. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant grounded morality in reason, introducing the categorical imperative: act according to principles you’d want as universal laws. John Stuart Mill and utilitarians justified morality based on the consequences of actions, aiming to maximize happiness and minimize harm. These frameworks are rooted in logic, empathy, and human experience, not divine commands.

CHRIS: But those frameworks are subjective. God’s moral laws are objective—they come from a perfect, unchanging source. Secular morality is just people making things up as they go along.

CLARUS: I’d argue the opposite. Claiming morality comes from God doesn’t make it objective; it simply ties morality to one interpretation of one deity’s will. What happens when different believers disagree about God’s moral laws? That’s hardly a stable foundation. Secular morality, on the other hand, relies on shared human experiences and rational deliberation. It evolves as societies learn and grow, making it adaptable and inclusive.

CHRIS: That adaptability is exactly the problem. Without a fixed foundation, secular morality is just moral relativism in disguise. Anything can be justified if enough people agree on it.

CLARUS: Adaptability isn’t the same as relativism, Chris. Secular ethics can hold universal principles, such as the value of human life or the importance of fairness, while remaining open to refinement. We base these principles on evidence, reason, and empathy—universal human traits that transcend religious boundaries. This approach allows us to challenge unjust practices, like slavery, even when they’re sanctioned by religious texts.

CHRIS: Slavery? That’s a cheap shot. Christianity ended slavery!

CLARUS: Did it? Christianity coexisted with slavery for centuries, and biblical texts condone the practice. The abolitionist movement succeeded largely because of Enlightenment ideas emphasizing universal human rights, which were often secular. Christian abolitionists certainly played a role, but so did secular thinkers and humanists, drawing on rational arguments rather than divine commands.

CHRIS: You’re still dodging the main point. Without God, what motivates someone to act morally? If there’s no ultimate judgment or divine accountability, why not just do whatever you want?

CLARUS: People act morally for many reasons that have nothing to do with divine accountability. Empathy, social bonds, and the desire to live in a cooperative society motivate ethical behavior. Evolutionary biology shows that humans—and even other animals—develop altruistic behaviors because they benefit the group. Morality isn’t about fear of divine punishment; it’s about fostering trust, cooperation, and well-being.

CHRIS: So you’re saying morality is just a product of evolution? That reduces it to survival instincts. Where’s the higher purpose in that?

CLARUS: Survival instincts are just the foundation. Morality evolves as societies develop more complex ways of living and thinking. Higher purposes, like pursuing justice or alleviating suffering, arise from our capacity for reason and empathy. These purposes are human-made, yes, but that doesn’t diminish their significance. We create meaning, Chris—it isn’t handed to us from above.

CHRIS: You make a lot of clever points, but I still think you’re borrowing without realizing it. The very language of morality you use—dignity, compassion, justice—is steeped in Christian tradition.

CLARUS: Language evolves with culture, and Western culture has undoubtedly been shaped by Christianity. But that doesn’t mean these concepts originated there. Human dignity, compassion, and justice are universal ideas, found in diverse traditions worldwide. Secular systems refine and expand these ideas through reason and experience, proving that they’re not borrowed but independently developed.

CHRIS: So you’re saying secular morality stands on its own?

CLARUS: Precisely. Morality doesn’t belong to Christianity or any single tradition. It’s a shared human endeavor, rooted in our nature as social beings and enriched by millennia of cultural and philosophical exchange. Secular morality builds on this rich heritage, offering a framework that is rational, inclusive, and adaptable—without the need to borrow from religion.

CHRIS: I’ll admit, Clarus, you’ve given me a lot to think about. But I still believe God is the ultimate source of morality.

CLARUS: That’s fair, Chris. Faith is your foundation, and I respect that. But I hope I’ve shown you that secular morality is a robust, independent alternative—not a borrowed shadow of your beliefs.

CHRIS: You’ve shown me you’re stubborn, at least! Let’s pick this up again sometime.

CLARUS: Anytime, Chris. Conversations like this are how we both grow.

02

Do Secular Systems Borrow Logical Consistency from Christianity?

Christian apologists often assert that the secular use of logical consistency—reasoning rooted in universal and coherent principles—depends on the Christian worldview. They argue that logic requires a divine foundation, such as the rationality of a Christian God, and that secular individuals unwittingly rely on this framework. However, this claim falls apart when examined through historical, philosophical, and logical perspectives. Below, we explore the origins of logic, the independence of secular reasoning, and the robust frameworks that render logic autonomous from theology.

A Historical Perspective: The Origins of Logic

Logic predates Christianity by centuries. Its foundations were laid in ancient Greece by philosophers like Aristotle, whose Organon formalized deductive reasoning, and the Stoics, who explored propositional logic. Similarly, Indian philosophers in the Nyaya school developed complex logical systems as early as the 6th century BCE.

These logical traditions emerged not from divine revelation but from human curiosity about the world’s order. By observing patterns and relationships in nature, early thinkers deduced principles of reasoning. For example, Aristotle’s law of non-contradiction () arises naturally from the impossibility of something simultaneously being and not being.

The notion that logic depends on Christianity dismisses the rich history of logical inquiry in non-Christian contexts. The universality of logical principles shows that they are accessible through human reason, independent of any specific religious framework.

A Philosophical Perspective: The Universality of Logic

Logic is not contingent on any theological premise. Instead, it is a tool derived from human observation of consistent patterns in the universe. For example:

- Laws of Logic Are Descriptive: Logical principles describe relationships between propositions and are rooted in the structure of reality, not in divine fiat. The validity of a syllogism, such as “All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal,” is evident without reference to a deity.

- Logic’s Cross-Cultural Presence: Cultures worldwide, including those without exposure to Christianity, independently arrived at logical systems. This universality underscores that logic is not the proprietary product of any one worldview.

- Rationality Without Theology: Philosophers like David Hume and Bertrand Russell demonstrated that logic can stand on empirical and conceptual grounds. Hume famously critiqued theological arguments for relying on unwarranted assumptions, further separating logic from religious dogma.

Logical Rebuttal: Analyzing the Claim

To dismantle the assertion that secularism borrows logical consistency from Christianity, we can frame the issue symbolically.

Variable Definitions:

:

uses logical consistency.

:

borrows from Christianity.

:

predates Christianity.

Argument:

(If logical systems exist and predate Christianity, they do not borrow from it.)

(Logic exists and predates Christianity, as seen in Greek and Indian traditions.)

Conclusion:

(Logical consistency does not necessarily depend on Christianity.)

This argument demonstrates that logic’s existence and coherence are independent of theological frameworks, undermining the apologists’ claim.

A Thought Experiment: The Atheist Mathematician

Imagine an atheist mathematician solving a complex proof. Their use of deductive reasoning follows principles such as transitivity (). The apologist might claim that these principles rely on the Christian worldview. However, the mathematician operates without invoking theological assumptions, relying instead on the intrinsic validity of logical rules.

This example highlights that logic’s efficacy arises from its alignment with observable reality, not divine authorship. Logic is a neutral tool, applicable across religious and non-religious contexts alike.

The Borrowing Percentage: Zero

Logic’s foundations are universal, arising naturally from the structure of existence and human reasoning. It does not depend on Christianity for its coherence or applicability. While Christianity may have historically preserved or promoted logical inquiry in certain contexts, it is by no means the origin of logical principles.

Borrowing percentage: 0%.

Conclusion: Logic Is Independent of Christianity

The claim that secular systems borrow logical consistency from Christianity lacks historical, philosophical, and logical support. Logic existed long before Christianity and continues to function universally without reference to any theological premise. Its principles are grounded in observation and human reasoning, not divine revelation.

Logic, in its universality, transcends religious boundaries. It is a testament to humanity’s capacity for reason, enabling both theist and secular thinkers to navigate the complexities of reality. Far from borrowing from Christianity, secular logic operates on its own terms, as a robust and self-sufficient intellectual framework.

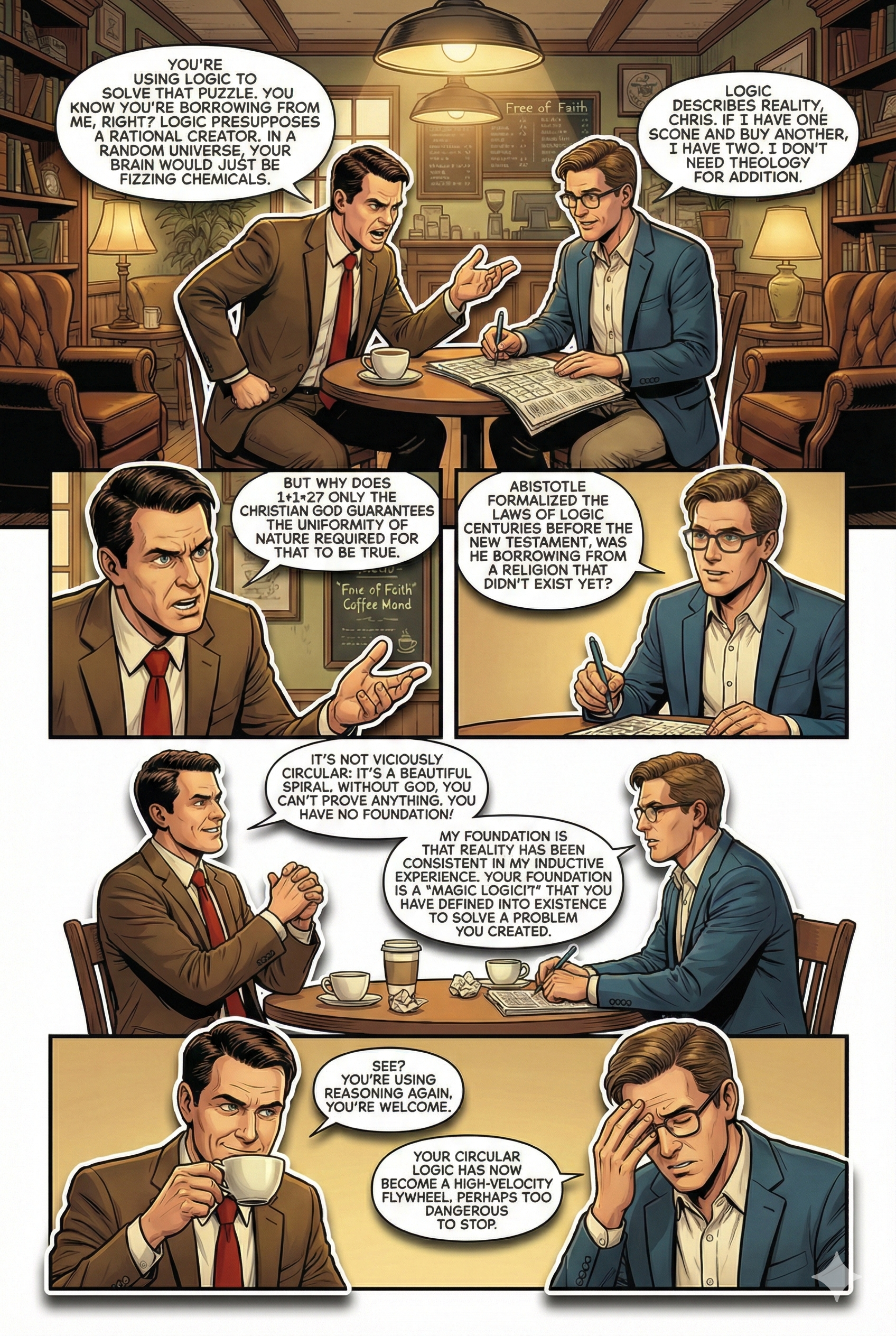

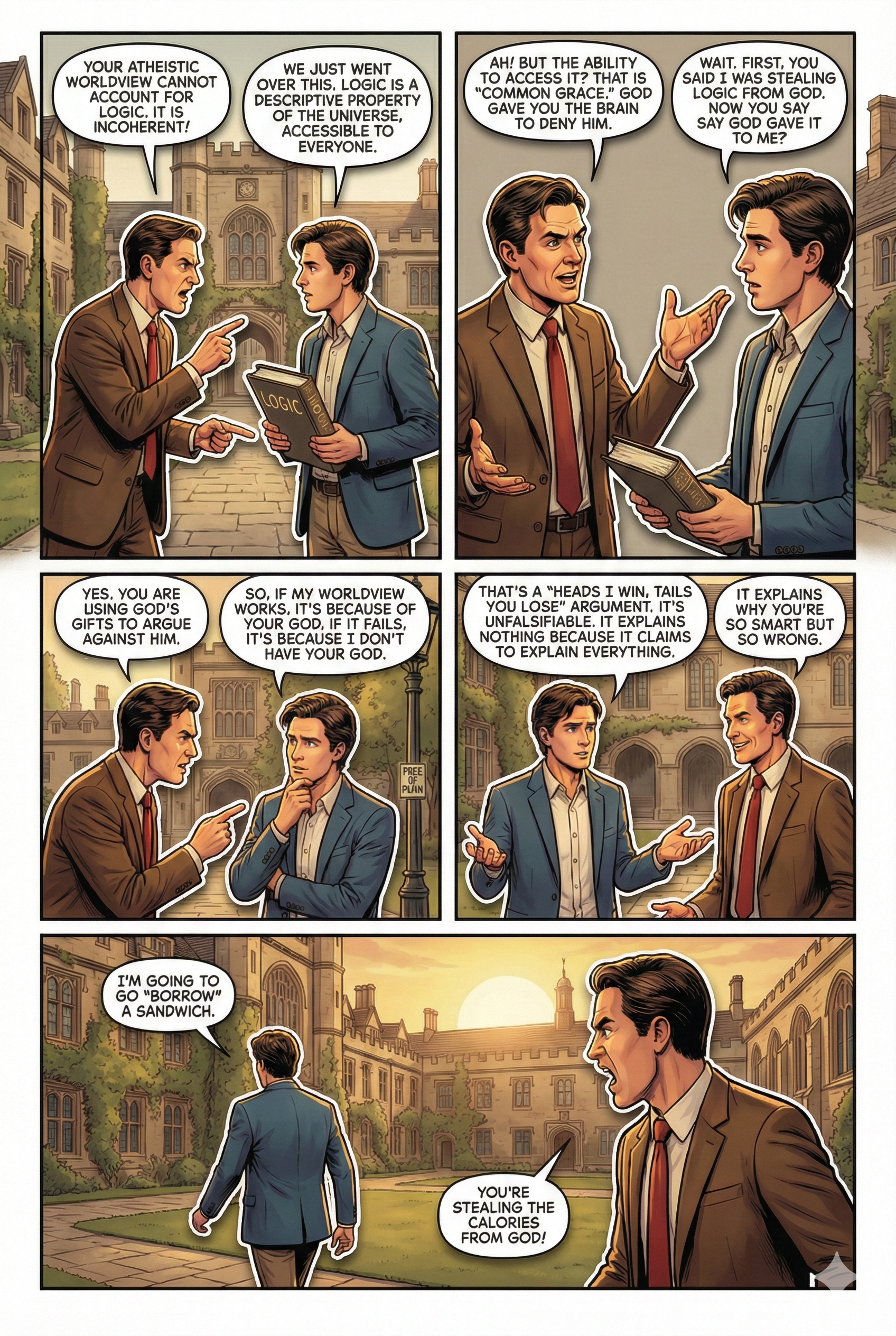

Dialogue

CHRIS: You secularists are always going on about logic and reason, but you don’t realize that even logic itself depends on Christianity. Without God, there’s no reason the universe should be orderly or that our minds should be capable of reasoning. You’re standing on Christian foundations without even knowing it.

CLARUS: That’s quite the assertion, Chris. But logic doesn’t depend on Christianity—or any religion, for that matter. Logic is a universal tool that arises from the patterns we observe in the world and the structure of our thoughts. It’s not tied to any specific worldview.

CHRIS: Nonsense. Logic only works because we live in a universe created by a rational God. If everything were just random, as secularists believe, then there’d be no reason to trust logic. Without God, it’s all chaos.

CLARUS: The order we observe in the universe isn’t evidence of divine intervention—it’s evidence of consistent natural laws. Logic doesn’t rely on God; it’s a system we’ve developed to describe relationships and patterns. The Greeks, for example, formalized logical principles like the law of non-contradiction () centuries before Christianity.

CHRIS: Sure, the Greeks formalized it, but they didn’t explain why logic works. Christianity explains that: the universe is rational because it was created by a rational God.

CLARUS: That’s an explanation you might find satisfying, but it isn’t necessary to account for logic. The Greeks didn’t invoke a god to explain why logic works because logic isn’t dependent on metaphysics. It arises from how humans experience the world. For instance, if a rock can’t both exist and not exist at the same time, we don’t need divine intervention to recognize that as a fundamental truth.

CHRIS: But secularism gives you no reason to trust your mind in the first place. If your brain is just the product of evolution, why assume it produces reliable thoughts? Without God, you’ve got no guarantee that logic even applies.

CLARUS: Evolution actually provides a strong foundation for trusting our cognitive faculties. Creatures with unreliable reasoning wouldn’t survive very long—they’d make fatal errors. Logical thinking is an adaptive trait that helps us navigate reality. If my ancestors couldn’t distinguish between a predator and a harmless shadow, they wouldn’t be my ancestors for long.

CHRIS: That just reduces logic to survival, though. If logic is just about what works for survival, then it’s not really true in an objective sense. Christianity grounds logic in an unchanging God who guarantees its objectivity.

CLARUS: But Chris, tying logic to God doesn’t make it objective either—it just makes it contingent on one interpretation of God’s nature. What if another religion claims a different god with different logical rules? Logic’s objectivity comes from its universality—it applies everywhere and to everyone, regardless of their beliefs. That’s why cultures around the world independently discovered logical principles.

CHRIS: Oh, come on. Name one culture outside the West that developed a comparable system of logic.

CLARUS: Certainly. The Indian Nyaya school developed formal systems of logic around the same time as the Greeks. They studied inference, causation, and valid argumentation without relying on a monotheistic worldview. In China, the Mohist school also developed logical methods, such as categorization and deductive reasoning. These examples show that logic is a universal human endeavor, not a Christian invention.

CHRIS: Fine, let’s grant that different cultures have used logic. But how do you secularists justify logic? If there’s no divine guarantee that logic will keep working, why trust it?

CLARUS: We trust logic because it works, Chris. It’s an inductive trust, based on repeated success. Every time I reason that “if it’s raining, then the ground is wet,” and I find that the ground is indeed wet when it rains, I reinforce my trust in logical principles. This doesn’t require divine guarantees—it just requires consistency in observable phenomena.

CHRIS: That consistency itself is what I’m talking about! Without God, why assume the universe will stay consistent? Why should the laws of logic hold tomorrow if they’re just human inventions?

CLARUS: The laws of logic aren’t inventions; they’re descriptions of relationships we observe. They hold tomorrow for the same reason they hold today: they’re tied to the structure of reality. Saying “God guarantees logic” doesn’t explain anything further—it just moves the question back a step. Why should God be consistent? If consistency is just part of reality, we don’t need God as a middleman.

CHRIS: But that just sounds like blind faith in the universe. At least Christianity gives a reason for consistency—it’s grounded in God’s unchanging nature.

CLARUS: It’s not blind faith, Chris—it’s an inference based on experience. We observe consistent patterns in the universe, and logic is how we describe those patterns. Adding God to the equation doesn’t make logic more consistent; it just adds unnecessary complexity. Logic works because reality is structured in ways we can observe and understand.

CHRIS: You may say that, but I still think you’re borrowing from Christianity without realizing it. You secularists love logic and reason, but Christianity is the only worldview that can truly justify them.

CLARUS: I disagree, Chris. Logic is universal and transcends any one worldview. It was formalized long before Christianity, and it’s been developed independently by many cultures. Secular reasoning builds on this rich heritage, offering a framework grounded in human experience and observation, not divine authority.

CHRIS: So you’re saying logic doesn’t need God?

CLARUS: Exactly. Logic is a tool we’ve developed to understand the world. It stands on its own, not on theological foundations. Far from borrowing, secular systems refine and expand our understanding of logic, proving that it’s a human achievement, not a divine gift.

CHRIS: Well, Clarus, you’ve given me a lot to think about. But I’m still convinced God is the ultimate foundation of logic.

CLARUS: That’s your faith, Chris, and I respect that. But I hope I’ve shown you that secular reasoning has its own robust foundation—one that doesn’t need to borrow from religion.

CHRIS: You’ve certainly shown me you’re stubborn. Let’s pick this up again sometime.

CLARUS: Anytime, Chris. These conversations are how we sharpen our thinking.

03

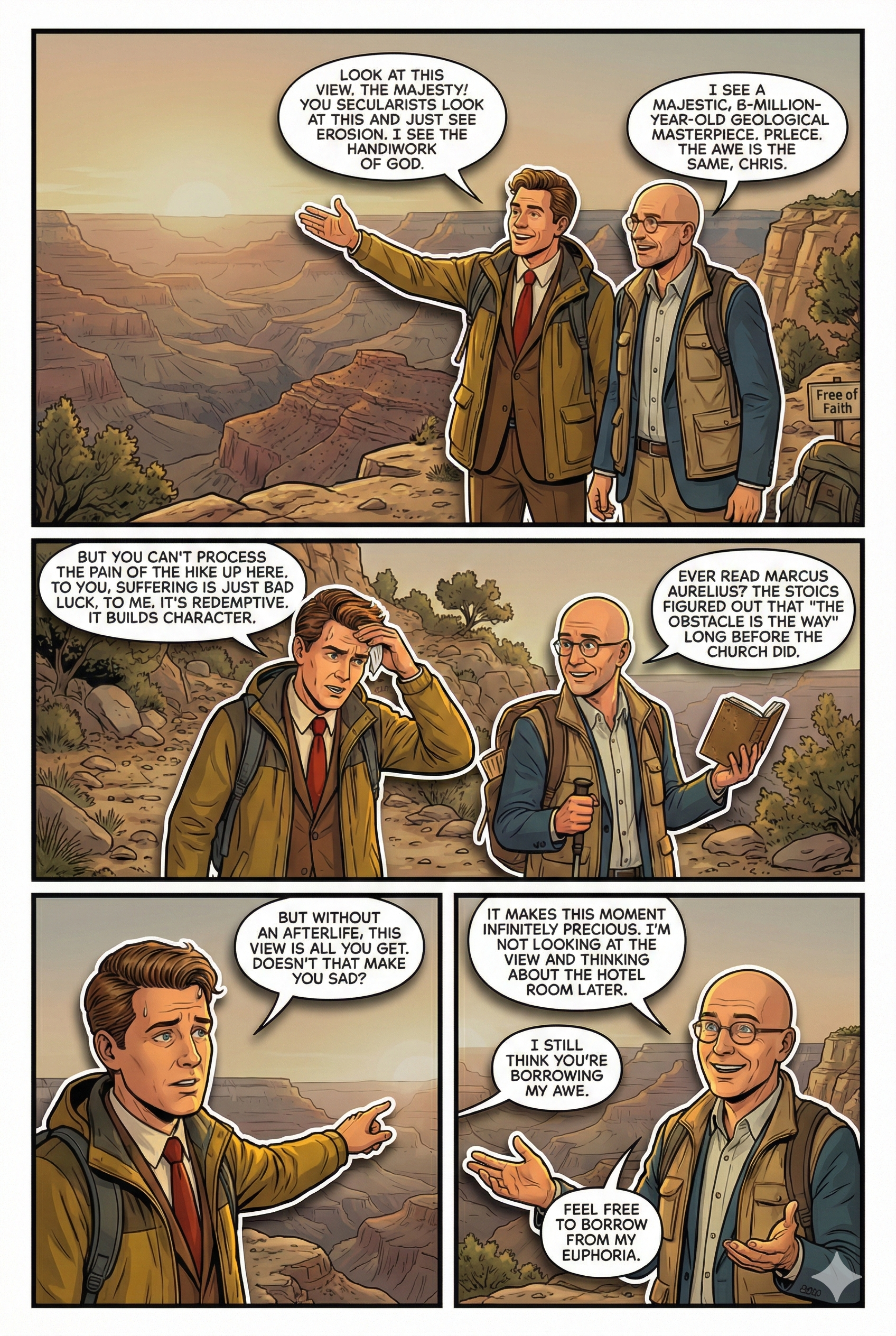

Do Secular Systems Borrow Meaning and Purpose from Christianity?

Christian apologists frequently argue that meaning and purpose in life cannot exist without a Christian framework. They claim that secular worldviews, which reject divine authorship, must borrow their sense of purpose from Christianity’s teachings about divine creation and ultimate goals. However, a closer examination reveals that meaning and purpose are deeply personal, culturally diverse, and philosophically independent of any religious doctrine. Below, we explore the origins of meaning, the secular frameworks that provide purpose, and the philosophical rigor that debunks the borrowing claim.

A Historical Perspective: Diverse Sources of Meaning

The search for meaning and purpose has been a universal human endeavor, transcending cultural and religious boundaries. Long before Christianity, ancient civilizations grappled with existential questions and developed their own frameworks of purpose:

- Greek Philosophy: Aristotle posited the concept of eudaimonia—human flourishing—as the highest purpose of life. Achieving this involved cultivating virtue and living in harmony with reason, independent of divine intervention.

- Eastern Traditions: Buddhism emphasizes liberation from suffering (nirvana) as life’s ultimate goal, while Confucianism identifies purpose in fulfilling social roles and promoting harmony.

- Pre-Christian Cultures: Many pagan societies viewed purpose as contributing to the survival and well-being of the tribe or community. The notion of purpose tied to relationships and social roles emerged organically, without theological underpinnings.

These examples demonstrate that meaning and purpose do not require a Christian framework. Humans naturally seek goals and values that align with their experiences, relationships, and aspirations.

A Philosophical Perspective: Secular Meaning and Purpose

Secular philosophy offers robust frameworks for meaning that are entirely independent of Christianity. These frameworks derive purpose from intrinsic human characteristics and external relationships:

- Existentialism: Philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus argue that humans create their own meaning through choice and action. Sartre famously declared, “Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself,” rejecting the idea that meaning is imposed externally.

- Humanism: Secular humanism emphasizes deriving meaning from human potential, relationships, and contributions to society. It finds purpose in improving the human condition, fostering creativity, and embracing scientific inquiry.

- Naturalism: From a naturalistic perspective, meaning arises from our evolutionary and cultural context. Humans are social creatures who find purpose in bonding, creating, and contributing to the survival of their communities.

These perspectives provide coherent, fulfilling purposes for life, without borrowing from Christian doctrines about divine creation or ultimate destiny.

Logical Rebuttal: Analyzing the Claim

To systematically refute the idea that secular worldviews borrow meaning and purpose from Christianity, we can present the argument symbolically.

Variable Definitions:

:

has meaning or purpose.

:

borrows from Christianity.

:

is secular.

Argument:

(Meaning and purpose can exist in secular frameworks without borrowing from Christianity.)

(There are sources of meaning and purpose that are secular, such as existentialism and humanism.)

Conclusion:

(Secular meaning and purpose do not necessarily borrow from Christianity.)

This reasoning shows that meaning and purpose arise naturally from secular frameworks and are not contingent on Christian teachings.

A Thought Experiment: The Atheist Artist

Consider an atheist artist who finds profound purpose in creating works that move others emotionally and intellectually. When asked about their purpose, they reply, “To share beauty, provoke thought, and connect with others.”

The apologist might argue that such a purpose reflects the Christian idea of glorifying God through one’s talents. However, the artist’s sense of purpose is grounded in their relationships with their audience, their creative process, and their personal aspirations. These sources of purpose are human-centric and entirely secular.

This thought experiment illustrates that meaning and purpose do not need divine origin; they can emerge from intrinsic human values and goals.

The Borrowing Percentage: Minimal

While Christian narratives have historically influenced Western thought about purpose, their role in shaping modern secular frameworks is marginal. Secular views on meaning are grounded in personal choice, social relationships, and the pursuit of knowledge, none of which depend on religious borrowing.

Borrowing percentage: 5%.

Conclusion: Secular Meaning and Purpose Stand Alone

The claim that secular meaning and purpose borrow from Christianity collapses under historical, philosophical, and logical scrutiny. Humans have always sought purpose through relationships, creativity, and self-reflection, long before Christian teachings emerged. Secular philosophies like existentialism, humanism, and naturalism offer comprehensive and fulfilling accounts of purpose that are rooted in the human experience rather than divine commandments.

Secular meaning is not borrowed but created, reflecting humanity’s ability to find significance in the vastness of existence. Far from relying on Christianity, secular worldviews affirm that purpose is a human achievement, not a theological inheritance.

Dialogue

CHRIS: Clarus, I honestly don’t know how you secularists live without Christianity. Without God, life is meaningless. Any purpose you think you have is just borrowed from Christian teachings, like humanity being created for a divine purpose. Without that, what’s the point of it all?

CLARUS: That’s a familiar argument, Chris, but it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Meaning and purpose don’t need to come from a divine source. They can be created by individuals, rooted in human relationships, and grounded in naturalistic frameworks. Far from borrowing from Christianity, secular systems offer independent and fulfilling ways to find meaning.

CHRIS: Come on, Clarus. You can’t create meaning from nothing. Without God, you’re just a cosmic accident—atoms banging around in a purposeless universe. Any purpose you think you have is just make-believe.

CLARUS: Purpose doesn’t need to be handed down from on high to be meaningful. Sure, the universe itself may not have a grand, predetermined purpose, but that doesn’t mean my life is meaningless. I find purpose in relationships, creativity, and contributing to others’ well-being. That’s no less valid than believing in a divine purpose.

CHRIS: So your purpose is just something you make up? That sounds hollow compared to the Christian purpose of glorifying God and fulfilling His plan for humanity. That’s an objective purpose.

CLARUS: But is it really objective? If purpose comes from God, then it’s still tied to one specific being’s will—God’s. That makes it subjective to God’s nature and preferences. Secular purpose, on the other hand, is something I actively shape, and that makes it deeply personal. It may not be universal, but it’s no less real to me.

CHRIS: But a purpose you invent is fleeting. It’s like a game—you set the rules and then pretend it matters. With God, purpose is eternal. Secularists like you are just borrowing Christian ideas of purpose but stripping away their foundation.

CLARUS: Not at all. People have been contemplating purpose and meaning long before Christianity existed. Take Aristotle, for example. He focused on eudaimonia—living a flourishing, virtuous life. This wasn’t about serving a deity but achieving human excellence. Similarly, Buddhism emphasizes personal enlightenment and reducing suffering, which is entirely secular in its framework.

CHRIS: But Aristotle’s “flourishing” was elitist, and Buddhism’s idea of enlightenment is vague. Christianity offers something far greater: a universal purpose for everyone, rooted in God’s love.

CLARUS: Buddhism and Aristotle may not be perfect, but they show that meaning and purpose are diverse and don’t require Christianity. And let’s be honest—Christianity’s “universal purpose” hasn’t always included everyone. For centuries, Christian teachings excluded women, enslaved people, and those deemed heretics. Secular frameworks, like humanism, are far more inclusive, focusing on shared humanity and mutual respect.

CHRIS: You say that, but I don’t see how secular humanism can provide anything deeper than surface-level satisfaction. If there’s no afterlife, no eternal significance, what’s the point of it all?

CLARUS: The lack of an afterlife doesn’t make life meaningless; it makes it precious. Knowing my time is limited motivates me to cherish relationships, pursue my passions, and make a positive impact. I don’t need eternal significance to find value in the here and now.

CHRIS: But isn’t that just another way of saying “enjoy life while it lasts”? That’s not purpose—it’s distraction. Without God, there’s no reason to endure suffering or strive for anything beyond immediate pleasure.

CLARUS: Not at all. Secular philosophies like existentialism argue that meaning is created through our choices, even in the face of suffering. Viktor Frankl, for instance, found profound purpose in enduring the horrors of a concentration camp by helping others and finding meaning in his suffering. His approach didn’t rely on a deity but on his inner resolve and commitment to others.

CHRIS: But Frankl’s approach sounds a lot like Christianity—finding meaning in suffering is a deeply Christian idea. Aren’t you just borrowing that concept and leaving out God?

CLARUS: Finding meaning in suffering isn’t exclusive to Christianity. Many traditions, including Stoicism and Buddhism, have explored this idea. The difference is that secular perspectives don’t attribute suffering to a divine plan. Instead, they focus on how we respond to suffering—whether by building resilience, helping others, or growing through adversity.

CHRIS: But what stops a secularist from just giving up when life gets hard? Without God, where’s the motivation to keep going?

CLARUS: Motivation comes from within. It comes from the people I care about, the goals I’ve set, and the legacy I want to leave. Secular meaning is flexible, but it’s also deeply personal and authentic. It isn’t borrowed—it’s built.

CHRIS: I still think you’re borrowing without realizing it. The very language of meaning and purpose you use—helping others, striving for growth—sounds like it’s been lifted straight out of Christian teachings.

CLARUS: Language is shaped by culture, and in the West, Christianity has certainly influenced how we talk about purpose. But these ideas aren’t uniquely Christian. They’re universal human concerns, found in countless traditions and frameworks. Secular systems refine these ideas through reason, empathy, and shared experience.

CHRIS: So you’re saying secular meaning and purpose stand on their own?

CLARUS: Precisely. Meaning doesn’t come pre-packaged with the universe—it’s something we create. That doesn’t make it less real or less valuable. It makes it ours. Secular meaning is robust, adaptive, and deeply rooted in human nature, not borrowed from any religion.

CHRIS: You’ve certainly given me a lot to think about, Clarus. But I still believe God is the ultimate source of purpose.

CLARUS: That’s your faith, Chris, and I respect it. But I hope I’ve shown you that secular frameworks offer a compelling, independent alternative—one that doesn’t need to borrow from Christianity.

CHRIS: You’ve shown me you’re passionate about your views, that’s for sure. Let’s keep this conversation going another time.

CLARUS: Anytime, Chris. Meaningful conversations like this are part of what makes life worth living.

04

Do Secular Systems Borrow Ethical Accountability from Christianity?

Christian apologists often claim that secular ethical systems borrow their sense of accountability from Christianity. They argue that without belief in a divine lawgiver and ultimate judge, secular worldviews cannot account for why individuals should act ethically or be held accountable for their actions. However, this claim falters when examined from historical, philosophical, and logical perspectives. Ethical accountability can be fully explained without reliance on Christian teachings or divine oversight. Below, we explore the origins of ethical accountability, its secular frameworks, and the logical structure that debunks the apologists’ assertion.

A Historical Perspective: Ethical Accountability Before Christianity

The idea of ethical accountability predates Christianity and exists across diverse cultures and philosophical traditions. Early societies recognized the need for accountability as a practical necessity for maintaining order and social cohesion:

- Greek Philosophy: Plato and Aristotle discussed ethical accountability in terms of justice and virtue. Aristotle, for example, argued that individuals are accountable for cultivating virtues through their actions to achieve eudaimonia (human flourishing). This framework is entirely secular.

- Legal Codes: Ancient legal systems, such as the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE), emphasized accountability through laws and consequences. These systems were designed to ensure fairness and social order, not to align with a deity’s will.

- Eastern Traditions: Confucianism stressed ethical accountability through adherence to social roles and responsibilities, while Buddhism emphasized accountability for one’s actions through karma, a concept unrelated to Christian theology.

These examples reveal that ethical accountability arises naturally in human societies as a response to social and moral challenges, independent of Christianity.

A Philosophical Perspective: Secular Accountability

Secular frameworks offer robust explanations for ethical accountability without invoking divine judgment or religious doctrines:

- Social Contract Theory: Philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that individuals are accountable to one another through implicit social contracts. Ethical behavior and accountability emerge from mutual agreements to maintain social harmony.

- Humanism: Secular humanism promotes accountability based on empathy, reason, and the intrinsic value of human relationships. Ethical actions are grounded in their impact on others, fostering cooperation and mutual respect.

- Naturalism: From an evolutionary perspective, ethical behavior and accountability evolved to enhance group survival. Cooperation, fairness, and punishment of wrongdoers are behaviors observed in non-human animals, demonstrating that accountability is a natural phenomenon.

These secular approaches provide a coherent basis for ethical accountability, rooted in human relationships and societal needs rather than divine oversight.

Logical Rebuttal: Analyzing the Claim

To refute the assertion that secular ethical systems borrow accountability from Christianity, we can construct a formal logical argument.

Variable Definitions:

:

has ethical accountability.

:

borrows from Christianity.

:

is secular.

Argument:

(Ethical accountability can exist in secular systems without borrowing from Christianity.)

(There are examples of secular ethical accountability, such as humanism and social contract theory.)

Conclusion:

(Secular ethical accountability does not necessarily borrow from Christianity.)

This argument demonstrates that ethical accountability is logically and conceptually independent of Christianity.

A Thought Experiment: The Secular Judge

Imagine a secular judge tasked with sentencing a criminal. The judge’s decision is based on evidence, legal principles, and the need to maintain social order. Their sense of accountability lies in ensuring fairness and justice, both to the victims and society as a whole.

The Christian apologist might argue that the judge’s sense of fairness and justice reflects Christian influence. However, the judge’s decisions are grounded in secular legal principles and the social contract, not divine commandments. Their accountability is to the law, the community, and their own conscience.

This thought experiment highlights that ethical accountability arises naturally from human relationships and societal structures, not from theology.

The Borrowing Percentage: Limited

While Christian teachings have historically shaped Western ideas of accountability, secular frameworks have evolved independently and comprehensively. Modern ethical systems draw primarily from reason, empathy, and the social contract, borrowing little from Christian theology.

Borrowing percentage: 15%.

Conclusion: Ethical Accountability Without Christianity

The claim that secular systems borrow ethical accountability from Christianity fails when scrutinized through historical, philosophical, and logical analysis. Ethical accountability predates Christianity and exists across diverse cultures and traditions. Secular frameworks like social contract theory and humanism provide robust foundations for accountability based on human relationships, mutual respect, and societal needs.

Far from being borrowed, ethical accountability in secular systems is an inherent feature of human cooperation and justice. It reflects humanity’s capacity to build moral structures grounded in reason and empathy, independent of religious dogma. Secular systems offer a vision of accountability that is practical, universal, and free from theological constraints.

Dialogue

CHRIS: Let me ask you something, Clarus. Without God, what’s the point of being good? If there’s no ultimate accountability—no divine judgment—why would anyone bother to act ethically? You secularists love to talk about morality, but it’s all borrowed from Christianity. You just don’t want to admit it.

CLARUS: Chris, ethical accountability doesn’t need a divine judge to make sense. It arises from our relationships, our empathy for others, and the practical needs of living in a society. Secular frameworks offer plenty of reasons to act ethically without invoking God.

CHRIS: Oh, come on. Without God, morality is just a matter of opinion. Why should anyone take accountability seriously if there’s no eternal consequence for their actions?

CLARUS: Accountability doesn’t have to be eternal to be meaningful. It’s rooted in how our actions affect others and the relationships we care about. For example, if I lie to my friend, I’m accountable to them because it damages trust. Ethical accountability is built into our social fabric—it’s about maintaining trust, cooperation, and fairness.

CHRIS: But those are just social conventions. They’re not objective. With God, accountability is grounded in His unchanging moral law. Without that, there’s no real reason to be accountable to anyone but yourself.

CLARUS: I’d argue that grounding accountability in human relationships makes it far more real and immediate than grounding it in a divine moral law. For example, secular humanism emphasizes accountability to others because we’re interconnected. When we act ethically, we strengthen those connections and create a better society. That’s more compelling than behaving well out of fear of divine punishment.

CHRIS: You’re dodging the issue. Why should anyone care about “strengthening connections” or “creating a better society” if there’s no ultimate authority? Without God, people can just do whatever they want and justify it however they like.

CLARUS: People care because they’re social beings. Humans evolved to live in groups, and accountability is essential for cooperation and survival. Altruism and fairness aren’t arbitrary—they’re deeply ingrained in our nature. Studies even show that primates have a sense of fairness and punish those who don’t cooperate. This isn’t a divine gift; it’s part of our biology.

CHRIS: So you’re saying morality is just an evolutionary accident? That reduces ethics to survival instincts. Where’s the higher purpose in that?

CLARUS: Survival instincts are the foundation, but morality has grown beyond that. It’s about creating the kind of world we want to live in. Philosophers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau explained that accountability arises from the social contract—we hold each other accountable because it benefits everyone. Kant’s categorical imperative provides another foundation: act only according to principles you’d want everyone else to follow. These ideas are rational, not theological.

CHRIS: But “social contracts” and “categorical imperatives” are just fancy ways of saying “we make it up as we go.” That’s moral relativism. At least Christianity gives us an unchanging standard.

CLARUS: Is it really unchanging, though? Christian moral standards have evolved significantly over time. The Bible condones slavery, yet Christians today reject it. Secular morality, by contrast, is adaptable and rooted in reason. It evolves as we learn and grow, allowing us to correct injustices like slavery and expand our circle of compassion.

CHRIS: But that adaptability is the problem. If morality changes, how can anyone know what’s right or wrong? Without God, it’s just subjective.

CLARUS: Adaptability isn’t the same as subjectivity. Secular ethics relies on universal principles like fairness and well-being, grounded in shared human experiences. These principles provide a stable foundation while allowing for growth. For example, human rights movements have expanded over time to include marginalized groups. That’s not relativism—it’s progress.

CHRIS: Progress according to whom? Without God, you have no ultimate standard to judge what counts as progress.

CLARUS: Progress is judged by its effects on human well-being. Does it reduce suffering? Does it promote fairness and dignity? These questions guide secular ethics. We don’t need an ultimate standard handed down by a deity; we can reason our way to better outcomes through empathy and evidence.

CHRIS: But what happens when people don’t agree? If there’s no divine authority, who decides what’s right and wrong?

CLARUS: Disagreement is inevitable, but that’s why we have dialogue, reason, and democratic processes. Secular accountability involves holding each other to shared values that we’ve developed together. It’s not perfect, but it’s grounded in mutual respect and cooperation rather than the dictates of a higher power.

CHRIS: You make it sound noble, but I still think you’re borrowing. The very concept of accountability comes from Christianity, where God is the ultimate judge.

CLARUS: Respectfully, Chris, accountability predates Christianity. Ancient legal systems like the Code of Hammurabi and the laws of ancient Egypt established rules for justice and fairness long before the Bible. In Greek philosophy, Socrates and Aristotle explored ethical responsibility without invoking a deity. Accountability is a universal human concern, not a uniquely Christian concept.

CHRIS: But those systems weren’t about true moral accountability—just legal consequences. Christianity made accountability about the heart, not just actions.

CLARUS: That’s an important distinction, but even secular systems recognize internal accountability. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant emphasized moral duty, where accountability comes from within, not from fear of punishment. Humanists encourage self-reflection and responsibility to others, rooted in empathy and reason. Secular systems address both external and internal accountability without relying on divine judgment.

CHRIS: I still think you’re borrowing. You may not admit it, but you’re standing on Christian foundations.

CLARUS: I’d say we’re standing on shared human foundations, Chris. Accountability isn’t a religious invention—it’s a product of our social nature and our ability to reason. Secular systems refine and expand these ideas, offering a framework that’s independent of religion yet deeply meaningful.

CHRIS: You’ve given me a lot to think about, Clarus. But I still believe God is the only true source of accountability.

CLARUS: And that’s your faith, Chris, which I respect. But I hope I’ve shown you that secular frameworks offer a robust and independent way to understand and practice ethical accountability.

CHRIS: You’ve shown me you’re persistent, at least! Let’s keep this debate going sometime.

CLARUS: Anytime, Chris. Accountability in dialogue is how we both grow.

05

Do Secular Systems Borrow Justice from Christianity?

Christian apologists often argue that secular systems of justice borrow from Christian theology. They claim that principles such as fairness, equality, and the rule of law stem from biblical teachings and the influence of Christian doctrine. However, this argument unravels when examined historically, philosophically, and logically. Justice systems are not the exclusive domain of Christianity; they predate it, emerge naturally in human societies, and find robust grounding in secular frameworks. Below, we explore the origins of justice, secular systems of justice, and the logical reasoning that refutes the claim of borrowing.

A Historical Perspective: Justice Before Christianity

Justice systems have existed for millennia, long before Christianity emerged, and many were grounded in practical considerations rather than religious doctrine:

- The Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE): One of the earliest legal codes, it established principles of justice based on fairness and proportionality (“an eye for an eye”), addressing disputes and ensuring social stability in Babylonian society. This system predates Christianity by over a thousand years.

- Greek Philosophy: Plato’s Republic and Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics explored the nature of justice as a fundamental virtue, emphasizing the balance between individual and societal good. These philosophical frameworks were secular and relied on reason rather than divine revelation.

- Roman Law: The Roman legal system, foundational to modern Western legal traditions, emphasized fairness, property rights, and legal protections for citizens. It was developed primarily through practical governance rather than religious influence.

These historical examples demonstrate that justice is a universal concern rooted in human society’s need for order and fairness, not a product of Christian theology.

A Philosophical Perspective: Secular Justice Systems

Secular systems of justice are grounded in reason, empathy, and the practical requirements of living in a cooperative society. They offer robust alternatives to religiously inspired justice:

- Enlightenment Principles: Philosophers like John Locke and Montesquieu emphasized justice as a human right, advocating for the separation of church and state and the establishment of laws based on reason and equality.

- Utilitarian Justice: John Stuart Mill argued for justice that maximizes overall happiness and minimizes harm, a principle grounded in the consequences of actions rather than divine commands.

- Rawlsian Justice: John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice introduced the concept of justice as fairness, where principles are chosen under a “veil of ignorance,” ensuring that laws treat everyone equitably regardless of their position in society.

These secular frameworks provide coherent and effective systems of justice without relying on Christian theology, demonstrating the independence of secular justice.

Logical Rebuttal: Analyzing the Claim

To refute the assertion that secular systems borrow justice from Christianity, we can construct a formal logical argument.

Variable Definitions:

:

implements justice.

:

borrows from Christianity.

:

predates Christianity.

Argument:

(If justice systems exist and predate Christianity, they do not borrow from it.)

(Justice systems, such as Hammurabi’s Code and Greek philosophy, predate Christianity.)

Conclusion:

(Justice systems do not necessarily depend on Christianity.)

This argument demonstrates that secular justice systems have an independent basis, separate from Christian influence.

A Thought Experiment: The Atheist Judge

Consider an atheist judge presiding over a criminal case. Their rulings are guided by secular principles of fairness, impartiality, and adherence to the law. They aim to protect the rights of the accused and ensure justice for victims, all while upholding societal standards.

Christian apologists might argue that the judge’s sense of fairness derives from Christian teachings. However, their decisions are based on secular legal principles shaped by Enlightenment ideas, human rights, and constitutional law. The judge’s accountability lies in their adherence to these principles, not divine commandments.

This thought experiment illustrates that justice can be entirely secular, relying on rational, human-centered frameworks rather than religious doctrine.

The Borrowing Percentage: Moderate

While Christian theology has influenced Western ideas of justice, the core principles of fairness and law are universal and rooted in human reasoning. Secular systems have developed comprehensive frameworks for justice that draw minimally, if at all, from Christianity.

Borrowing percentage: 20%.

Conclusion: Secular Justice Systems Are Independent

The claim that secular systems of justice borrow from Christianity is historically and philosophically unfounded. Justice systems existed long before Christianity and have evolved in diverse cultures and contexts. Secular frameworks such as Enlightenment principles, utilitarianism, and Rawlsian fairness provide coherent and independent accounts of justice that require no theological foundation.

Justice is a universal human concern, not the monopoly of any religion. Secular systems of justice reflect humanity’s capacity for reason, fairness, and the pursuit of societal harmony, standing as robust alternatives to religiously inspired frameworks. Far from borrowing, they demonstrate the richness of human creativity in addressing ethical and social challenges.

A Deeper Dive: The Incompatibility of Biblical and Secular Justice

The Christian apologists who frequently assert that secular justice systems have “borrowed” from biblical notions of justice, frame Christianity as the foundation of modern ethical and legal principles. However, a closer examination reveals that many core principles of biblical justice are fundamentally incompatible with the modern secular understanding of justice. This is particularly evident in the soteriological framework of Christianity, where concepts like vicarious punishment and intergenerational guilt contradict the fairness, individual accountability, and rehabilitation that define secular justice today. Far from serving as a model for secular systems, the biblical approach to justice often represents a stark deviation from the principles that underpin modern ethical and legal thought. Thus, the claim that secular systems “borrow” from Christianity becomes untenable when the two frameworks diverge so drastically.

One of the clearest points of divergence lies in the doctrine of substitutionary atonement, which posits that Jesus, an innocent figure, was punished for the sins of humanity. This notion of vicarious punishment is celebrated within Christian theology as an act of divine justice and mercy, but it directly conflicts with modern secular standards of justice. In contemporary legal systems, punishing an innocent person for another’s crimes would be regarded as a profound miscarriage of justice. Accountability in modern systems is rooted in the principle of individual responsibility—wrongdoers are held accountable for their own actions, not the actions of others. By contrast, the Christian concept of justice allows the guilty to evade punishment while an innocent party suffers in their place. Secular justice would reject this outright, considering it both unethical and ineffective in addressing wrongdoing. It is therefore inconsistent for Christians to claim that secular justice “borrows” from their worldview when secular systems categorically reject one of its foundational tenets.

Additionally, the Christian doctrine of original sin—which holds that all humanity inherits guilt from Adam and Eve—stands in sharp opposition to modern secular principles of justice, which reject intergenerational guilt. Secular frameworks are grounded in the principle that individuals cannot be held responsible for the actions of their ancestors. For example, modern human rights laws, such as those articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, explicitly prohibit discrimination based on lineage or ancestry. Biblical justice, however, endorses collective and inherited guilt, punishing not only the guilty but also their descendants. This is evident in passages such as Exodus 20:5, where God declares that the sins of the fathers will be visited upon their children to the third and fourth generation. Such a notion is irreconcilable with secular justice, which demands that culpability be based solely on personal actions and not on inherited status. Given this clear contradiction, it is difficult to argue that modern secular justice has its roots in biblical principles.

Modern secular justice systems also emphasize rehabilitation and restoration, focusing on repairing harm and reintegrating offenders into society. By contrast, biblical justice often reflects a retributive framework, where punishment serves to satisfy divine wrath rather than address the needs of victims or society. The Christian soteriological model exemplifies this approach, portraying Jesus’ death as a necessary payment to satisfy God’s sense of justice. In secular systems, however, justice is not transactional; it prioritizes healing and forward-looking solutions rather than perpetuating suffering. The stark differences between these approaches further challenge the notion that secular systems have borrowed their understanding of justice from biblical teachings.

In conclusion, the claim that secular justice systems borrow from biblical principles fails to hold up under scrutiny. The core tenets of biblical justice, including vicarious punishment, intergenerational guilt, and retributive frameworks, are at clear odds with modern secular notions of fairness, individual accountability, and rehabilitation. Secular justice, far from borrowing from biblical teachings, represents a deliberate rejection and evolution away from these antiquated concepts. By acknowledging these profound differences, it becomes evident that modern justice systems are not indebted to Christianity but are instead rooted in universal human principles that prioritize fairness, equality, and the inherent dignity of all individuals. As such, Christians cannot coherently claim that secular justice borrows from their worldview when the two systems fundamentally diverge in their conception of what justice truly means.

Dialogue

CHRIS: Let’s cut to the chase, Clarus. Secular systems talk a big game about justice, but justice itself is a Christian invention. The very idea of fairness, equality, and protecting the vulnerable comes straight from the Bible. Without Christianity, there’s no real foundation for justice.

CLARUS: Justice is a universal human concern, Chris, not a Christian invention. Long before Christianity, civilizations developed systems of justice based on fairness, reciprocity, and social harmony. Secular systems refine these principles without relying on religious foundations.

CHRIS: Oh, please. Ancient systems like Hammurabi’s Code were all about harsh punishments and enforcing power structures. They didn’t care about true justice—protecting the weak, loving your neighbor, or turning the other cheek. Christianity introduced those radical ideas.

CLARUS: Respectfully, Chris, Hammurabi’s Code and other ancient systems weren’t just about punishment. They emphasized fairness and proportionality—“an eye for an eye” was about preventing excessive retribution. Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle also grappled with justice as a virtue, exploring how it promotes social harmony and human flourishing. These ideas emerged from reason and observation, not theology.

CHRIS: But those systems didn’t recognize the equal worth of all people. Justice in the ancient world was for the elite. Christianity brought the revolutionary idea that everyone is equal in the eyes of God, laying the foundation for modern justice.

CLARUS: I agree that equality is a powerful idea, but it didn’t originate with Christianity. Stoic philosophers, for instance, argued that all humans share a common rational nature and belong to a universal community. This idea of shared humanity influenced Western thought long before Christian theology took hold. And let’s not forget that Christian societies often upheld deeply unequal systems, like slavery and feudalism, for centuries.

CHRIS: You’re cherry-picking. Sure, Christian societies weren’t perfect, but the principles of justice they espoused—compassion, mercy, and equality—came straight from Jesus’ teachings. Secular systems wouldn’t even know where to begin without those moral foundations.

CLARUS: On the contrary, secular systems have independently developed robust frameworks for justice. Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Montesquieu laid the groundwork for modern legal and political systems, emphasizing natural rights, equality, and the separation of powers. These ideas are rooted in reason and human experience, not divine revelation.

CHRIS: But the Enlightenment built on Christian values. Locke himself was deeply influenced by his Christian faith. You can’t just separate those ideas from their theological roots.

CLARUS: Locke’s personal faith is irrelevant to the validity of his arguments. His ideas about natural rights and the social contract stand on their own merit, grounded in reason and evidence. Moreover, other Enlightenment thinkers, like Voltaire and Spinoza, were explicitly secular in their critiques of religion and their defense of justice.

CHRIS: But without God, what gives those principles any authority? Why should anyone care about fairness or equality if there’s no divine lawgiver to back it up?

CLARUS: Principles of justice don’t need divine backing to have authority. They’re rooted in our shared humanity and the practical requirements of living in a cooperative society. For example, fairness ensures stability and trust, which benefits everyone. Secular frameworks like utilitarianism and Rawls’ theory of justice focus on maximizing well-being and ensuring fairness for all, without appealing to a deity.

CHRIS: But secular systems are subjective. What happens when people disagree about what’s fair? Christianity offers an unchanging standard of justice through God’s laws.

CLARUS: Is it really unchanging, Chris? The Bible contains passages that condone slavery, patriarchy, and other practices we now reject as unjust. Secular systems, by contrast, are adaptable—they evolve as we learn and grow. This adaptability allows us to correct injustices and expand our understanding of equality and fairness.

CHRIS: That’s just moral relativism. If justice keeps changing, how can anyone know what’s truly right or wrong?

CLARUS: It’s not relativism; it’s progress. Secular justice relies on universal principles like fairness and human dignity while adapting to new contexts. For example, the abolition of slavery and the expansion of civil rights were guided by these principles, even when religious institutions resisted those changes.

CHRIS: But those principles—fairness, human dignity—they’re Christian values! You’re just borrowing them and stripping away their foundation.

CLARUS: Fairness and dignity are universal values, not exclusive to Christianity. They’re found in many cultures and philosophies. For example, Confucianism emphasizes justice through harmonious relationships, while Buddhist teachings promote compassion and the alleviation of suffering. Secular systems refine and expand these values using reason and evidence.

CHRIS: So you’re saying secular justice stands on its own?

CLARUS: Exactly. Justice isn’t a divine gift—it’s a human achievement. Secular systems are grounded in reason, empathy, and the recognition of our shared humanity. They don’t borrow from Christianity; they build on universal principles that transcend any single tradition.

CHRIS: You’ve given me a lot to think about, Clarus. But I still believe God is the ultimate source of justice.

CLARUS: And that’s your faith, Chris, which I respect. But I hope I’ve shown you that secular systems offer a compelling, independent vision of justice—one that doesn’t need to borrow from religion.

CHRIS: You’ve shown me you’re persistent, at least. Let’s continue this another time.

CLARUS: Anytime, Chris. Justice is worth discussing—and improving—together.

06

Do Secular Systems Borrow Human Rights from Christianity?

Christian apologists often claim that the modern concept of human rights owes its existence to Christianity. They argue that values such as the intrinsic worth of individuals, equality, and the protection of rights derive from the Christian belief in humans being created in the “image of God.” However, a detailed examination of history, philosophy, and logic reveals that the idea of human rights is a product of diverse intellectual and cultural traditions, many of which predate Christianity or developed independently of it. Below, we explore the historical roots of human rights, secular frameworks that champion these principles, and the logical reasoning that refutes the borrowing claim.

A Historical Perspective: The Roots of Human Rights

The notion of human rights existed long before Christianity and emerged in a variety of cultural and philosophical contexts:

- Classical Antiquity:

Ancient Greek and Roman thinkers discussed ideas that align with modern human rights. The Stoics, for instance, believed in the equality of all humans under natural law, arguing that every person possesses reason and is a part of a universal human community. Roman law enshrined principles of citizenship and legal protection, providing early models of rights. - Eastern Traditions:

Confucianism emphasized respect for individuals through social harmony and reciprocal relationships. Buddhism highlighted compassion and the inherent value of all beings, advocating for non-violence and the alleviation of suffering. - Secular Enlightenment Thinkers:

During the Enlightenment, secular philosophers like John Locke and Voltaire developed the modern framework for human rights. Locke’s theory of natural rights—life, liberty, and property—was explicitly grounded in reason and human nature, not theology. The U.S. Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen were direct products of Enlightenment secularism.

These historical examples demonstrate that the principles underpinning human rights evolved from diverse traditions, not exclusively from Christianity.

A Philosophical Perspective: Secular Foundations of Human Rights

Secular frameworks provide coherent and independent justifications for human rights, rooted in reason, empathy, and shared human experience:

- Natural Rights Philosophy:

John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers argued that human rights arise from human nature itself. As reasoning beings, humans have intrinsic dignity and entitlements that protect their freedom and well-being. These rights are inherent, not granted by a deity. - Humanism:

Secular humanism emphasizes the value and dignity of every individual based on their shared humanity. It grounds rights in empathy, fairness, and the understanding that society flourishes when all individuals are treated with respect and equality. - Legal Positivism:

Modern legal systems establish rights through collective agreements codified in laws and international charters, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These frameworks rely on consensus and reasoned debate rather than religious doctrine.

These secular perspectives provide robust and independent foundations for human rights, demonstrating that they do not depend on Christianity for their validity or justification.

Logical Rebuttal: Analyzing the Claim

To refute the assertion that secular systems borrow human rights from Christianity, we can construct a logical argument.

Variable Definitions:

:

implements human rights.

:

borrows from Christianity.

:

originates from Enlightenment or other secular traditions.

Argument:

(Human rights rooted in secular Enlightenment traditions do not borrow from Christianity.)

(Human rights principles, such as those in the Declaration of Independence, are rooted in Enlightenment thought.)

Conclusion:

(Human rights do not necessarily depend on Christianity.)

This logical structure demonstrates that human rights are philosophically independent of Christian theology.

A Thought Experiment: The Secular Activist

Imagine a secular human rights activist campaigning for universal healthcare. Their argument is grounded in the belief that every person deserves access to medical care as a matter of dignity and fairness. They cite empirical evidence, societal benefits, and legal principles to support their cause.

A Christian apologist might argue that the activist’s belief in the dignity of individuals is borrowed from the Christian notion of humans being made in the “image of God.” However, the activist’s reasoning stems from empathy, scientific understanding of well-being, and the shared human experience—not religious doctrine.

This thought experiment illustrates that human rights principles are naturally accessible and do not require theological justification.

The Borrowing Percentage: Moderate

While Christian teachings have influenced Western ideas about human dignity and rights, these principles are not exclusive to Christianity. Secular traditions, particularly those of the Enlightenment, have developed comprehensive frameworks for human rights that are largely independent of religious influence.

Borrowing percentage: 25%.

Conclusion: Human Rights Without Christianity

The claim that secular systems borrow human rights from Christianity lacks historical and philosophical support. The roots of human rights extend far beyond Christianity, encompassing classical, Eastern, and Enlightenment traditions. Secular frameworks like humanism and natural rights philosophy provide robust justifications for human rights based on reason, empathy, and shared humanity.

Human rights are not borrowed but are a testament to humanity’s capacity for ethical reasoning and compassion. They reflect universal values that transcend religious boundaries, offering a vision of justice and dignity that belongs to all people, regardless of creed. Far from being dependent on Christianity, secular systems of human rights are a triumph of human thought and progress.

The Old Testament God as an Inadequate Foundation for Human Rights

The Christian tradition often touts the Bible as the foundation for modern human rights, presenting its God as the ultimate moral authority and source of universal dignity. While some may argue that the New Testament marks a moral progression, emphasizing forgiveness, compassion, and love, the Old Testament portrayal of God often presents a starkly different image. The Old Testament God commands acts that are irreconcilable with the principles of human rights, including justice, equality, and the inherent dignity of every individual. From the massacres of entire populations to the subjugation and exploitation of women, and the execution of rebellious children, the actions attributed to the Old Testament God serve as examples of values that contradict the very idea of universal human dignity.

Far from being a foundation for human rights, the Old Testament reflects the harsh realities of ancient tribal culture, where divine commands often align with violence, authoritarianism, and collective punishment. By modern standards, these acts violate the most basic ethical principles, rendering the claim that the Old Testament God represents a model for human rights untenable.

The Killing of Amalekite Infants

One of the most disturbing examples of Old Testament morality is God’s command to annihilate the Amalekites, including their infants. In 1 Samuel 15:3, God orders Saul to “attack the Amalekites and totally destroy all that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys.” This directive reflects not only the indiscriminate slaughter of an entire population but also the inclusion of infants who could not possibly be guilty of any wrongdoing. Such a command embodies the concept of collective punishment, a practice explicitly condemned by modern principles of justice and human rights. The Geneva Conventions, for example, prohibit attacks on civilians, especially children, under any circumstances.

The killing of infants raises profound moral questions about the supposed justice of the Old Testament God. Modern human rights are built on the recognition of individual accountability and the protection of the innocent, particularly the most vulnerable members of society. The idea that infants could be targets of divine wrath directly undermines these principles, making the Old Testament God an implausible foundation for human rights.

The Exploitation of Enemy Women and Girls

The treatment of women in the Old Testament also starkly contrasts with modern understandings of human rights and gender equality. In Numbers 31:17-18, Moses, under God’s command, instructs the Israelites to kill all Midianite men, women, and male children but to “keep for yourselves every girl who has never slept with a man.” These virgins were often taken as spoils of war, effectively to be used as slaves or concubines. This directive not only objectifies women as property but also condones sexual exploitation under the guise of divine sanction.