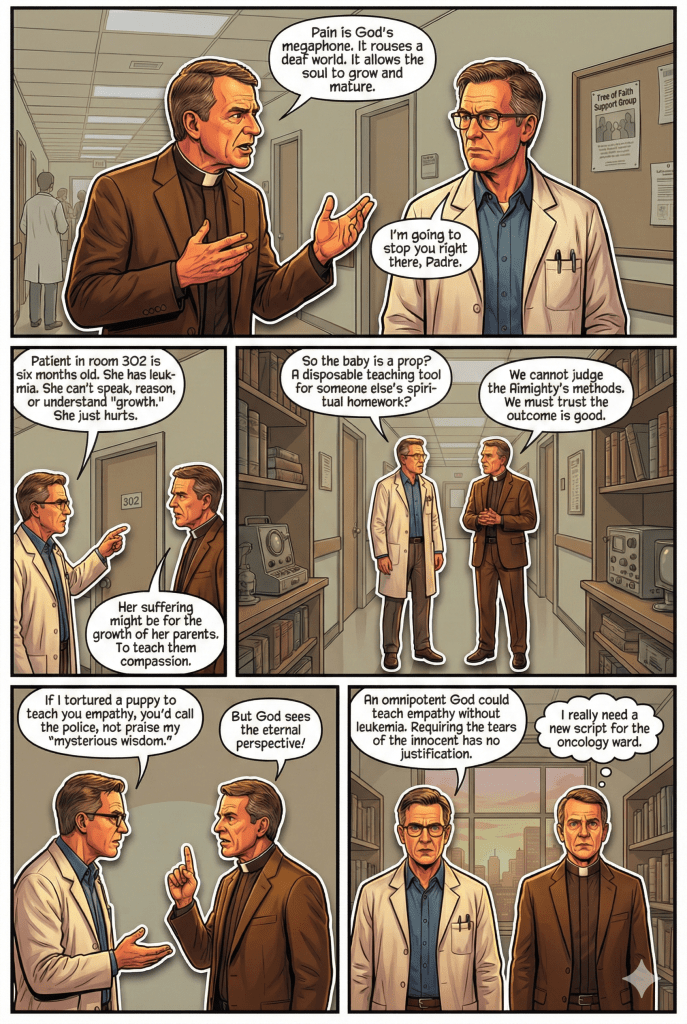

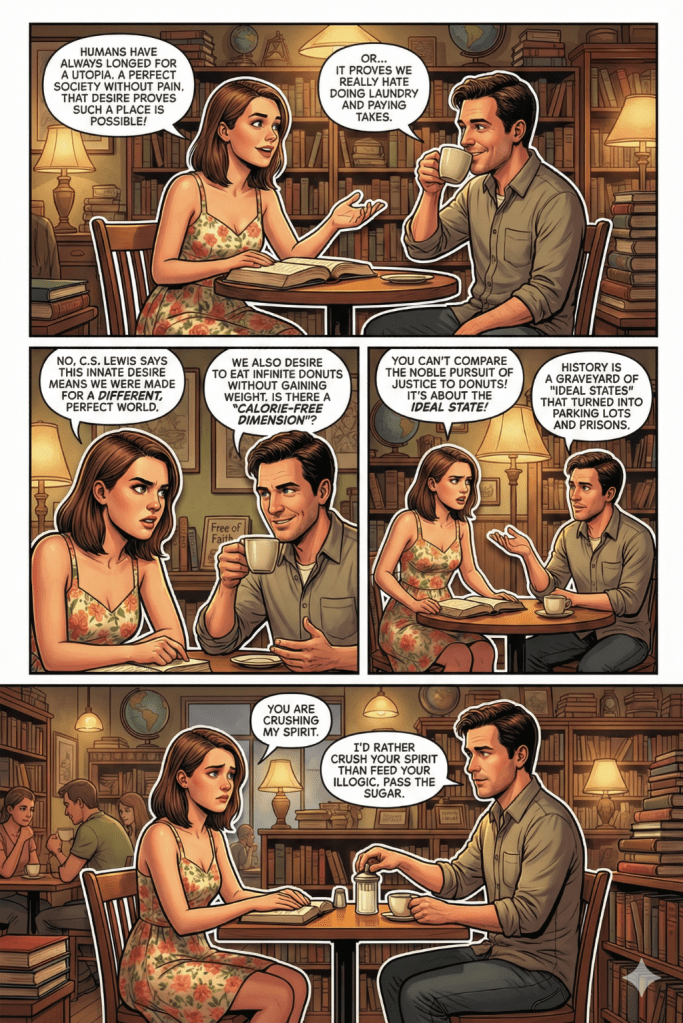

/#1/ Lewis’ Argument from Innate Desires

Examining the Principle of Correspondence for Innate Desires

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Desire suggests that every innate human desire corresponds to a real object capable of fulfilling it. While this argument resonates emotionally and appears logically sound at first glance, it relies on the unproven principle that every innate desire corresponds to reality. This essay critiques the universality of this principle by presenting examples of innate desires that fail to correspond to real objects. Each counterargument includes syllogistic formulations, symbolic logic, and accompanying commentary to clarify the argument and its critique.

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Desire

Lewis’ argument can be summarized as follows:

- Every innate human desire corresponds to a real object that can satisfy it.

- Humans possess an innate desire for something transcendent and infinite that no earthly object can satisfy.

- Therefore, a transcendent and infinite reality (e.g., Heaven or God) must exist to fulfill this desire.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent an innate desire.

- Let

represent a real object satisfying

.

- The principle assumes:

.

- Applied to transcendence:

- Conclusion:

Commentary:

This formulation is valid in its structure, but the soundness of the argument depends on the truth of the universal premise (). This premise assumes that every innate desire must correspond to reality, which is precisely what the following counterexamples will challenge.

Counterarguments

1. Desire for Immortality

Humans universally long for immortality, yet there is no evidence that such a state exists.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Humans desire immortality, but there is no evidence for its existence.

- The desire for immortality is better explained as a psychological response to the fear of death.

- Therefore, the desire for immortality does not imply its existence.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the innate desire for immortality.

- Counterexample:

Commentary:

The counterexample shows that the desire for immortality exists () but lacks a corresponding real object (

). This undermines the universal premise that

.

2. Desire for Perfect Justice

Humans innately desire perfect justice, yet the observable world fails to provide such a reality.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Humans desire perfect justice, but the world demonstrates persistent injustice.

- The desire for perfect justice likely arises from evolved social instincts for fairness and cooperation.

- Therefore, the desire for perfect justice does not necessitate its existence.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the innate desire for justice.

- Counterexample:

Commentary:

While the desire for justice () is universal, there is no evidence for a corresponding perfect justice (

). This shows that desires can reflect ideals rather than existing realities.

3. Desire for Absolute Control

Humans often long for complete control over their circumstances. However, this desire is inherently unattainable in a world governed by randomness and external forces.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Humans desire absolute control, but no one can achieve it in a world influenced by chance and determinism.

- The desire for control is a psychological response to anxiety, not evidence of attainable control.

- Therefore, the desire for absolute control does not imply its existence.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the desire for absolute control.

- Counterexample:

Commentary:

The universal premise () is further weakened here. Desires like control (

) may arise from psychological needs rather than corresponding to real objects.

4. Desire for Cosmic Purpose

Many people long for a cosmic purpose that transcends individual existence. However, there is no empirical evidence for such a purpose.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Humans have an innate desire for cosmic purpose, but no evidence supports the existence of such a purpose.

- The desire for purpose is likely a by-product of human abstraction and imagination.

- Therefore, the desire for cosmic purpose does not prove its existence.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the desire for a cosmic purpose.

- Counterexample:

Commentary:

The symbolic logic shows that abstract desires () may lack corresponding realities (

), illustrating the limitations of Lewis’ principle.

5. Desire for Eternal Happiness

Eternal happiness, defined as a state devoid of suffering, is a universal human desire. Yet the natural world provides no evidence for such a reality.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Humans desire eternal happiness, but no observable evidence suggests such a state exists.

- The desire for happiness reflects idealized notions of transient pleasures, not evidence of eternal fulfillment.

- Therefore, the desire for eternal happiness does not correspond to reality.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the desire for eternal happiness.

- Counterexample:

Commentary:

The universal premise () is critically challenged here, as desires like happiness (

) do not guarantee the existence of a corresponding eternal reality.

Conclusion

The principle that “every innate desire corresponds to a real object” fails to account for several significant counterexamples. Desires for immortality, perfect justice, absolute control, cosmic purpose, and eternal happiness are better explained as psychological or evolutionary by-products, not evidence of metaphysical realities. Each counterexample illustrates that innate desires () can exist without corresponding objects (

), thereby undermining Lewis’ argument. While rhetorically powerful, the Argument from Desire lacks the logical and empirical foundation to prove the existence of a transcendent reality.

The Arbitrary Selection of Desires in C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Desire

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Desire asserts that every innate human desire corresponds to a real object capable of fulfilling it. From this, Lewis reasons that humanity’s deep longing for transcendence and ultimate fulfillment points to the existence of a corresponding transcendent reality (e.g., Heaven or God). While rhetorically powerful, this argument suffers from a critical oversight: Lewis arbitrarily selects a subset of human desires to support his conclusion while ignoring other desires that do not align with his theological framework. This selective approach undermines the argument’s coherence and universality.

C.S. Lewis’ Core Assumption

Lewis’ argument is grounded in the principle that every innate desire must correspond to a real object. He cites examples such as hunger (corresponding to food) and thirst (corresponding to water) as evidence of this principle. From this, he extrapolates that humanity’s longing for transcendence implies the existence of a transcendent reality.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent an innate human desire.

- Let

represent a real object satisfying

.

- Principle:

.

- Applied to transcendence:

.

This principle assumes universality, yet Lewis only cites desires that support his conclusion. Desires for sexual partners, power, and wealth—equally innate and widespread—are conspicuously absent from his analysis.

1. Desire for Sexual Partners

The desire for sexual relationships is among the most universal and powerful human drives. It arises biologically, culturally, and emotionally in nearly all societies.

Counterpoint to Lewis:

- The desire for sexual partners is innate and fundamental, yet it does not correspond to a singular or universal real object.

- For example, not all individuals attain satisfying or lasting relationships, and some remain celibate by choice or circumstance.

- This desire is often frustrated or redirected, undermining the assumption that all desires correspond directly to external realities.

Implications: If the argument hinges on the universality of fulfillment, the unfulfilled desires for sexual relationships cast doubt on Lewis’ premise. A more plausible explanation is that human desires often reflect biological imperatives or cultural constructs, not metaphysical truths.

2. Desire for Power

Humans frequently desire power—over others, over circumstances, or over their own lives. This desire manifests in political ambitions, social hierarchies, and personal autonomy.

Counterpoint to Lewis:

- The desire for power is not universally satisfied, even for those who attain positions of authority.

- Many leaders find that the pursuit of power is insatiable or ultimately unfulfilling.

- This suggests that innate desires can exist independently of external realities that fully satisfy them.

Implications: Lewis’ principle cannot accommodate desires like power, which are often infinite in scope and subjectively defined. The longing for power highlights that human desires are shaped as much by psychological and societal factors as by any correspondence to real objects.

3. Desire for Wealth

The desire for wealth—resources, material possessions, or financial security—is a pervasive human drive. This desire varies in intensity but is undeniably present across cultures and historical periods.

Counterpoint to Lewis:

- The desire for wealth often leads to disappointment or dissatisfaction, even among those who achieve great riches.

- Studies in psychology reveal a phenomenon known as the “hedonic treadmill,” where individuals quickly adapt to increased wealth without sustained happiness.

- This undermines the notion that wealth as a desire corresponds to an ultimate or enduring external fulfillment.

Implications: Wealth provides a clear example of an innate desire that fails to meet Lewis’ standard of a corresponding reality. Its fulfillment is fleeting, context-dependent, and often illusory.

4. Desire for Fame

The desire for fame or recognition reflects a fundamental human need for social validation and esteem. Yet fame is ephemeral, culturally contingent, and often destructive.

Counterpoint to Lewis:

- Not everyone achieves fame, and those who do frequently find it hollow or detrimental to well-being.

- Historical examples of disillusioned celebrities underscore this point.

- This desire exemplifies how innate human drives can lead to outcomes that are not enduring or inherently fulfilling.

Implications: The desire for fame directly challenges Lewis’ assertion that every desire corresponds to a real and satisfying object. Fame may exist as an external reality, but its fulfillment is highly subjective and rarely aligns with expectations.

5. Desire for Transcendence: A Special Pleading?

Lewis’ argument uniquely elevates the desire for transcendence above other innate desires, claiming it uniquely points to a corresponding reality. Yet the mechanism for distinguishing transcendence from other desires is unclear and inconsistent.

Counterpoint to Lewis:

- If desires for transcendence are innate and correspond to an external reality, why not apply the same reasoning to other desires like power or wealth?

- By arbitrarily excluding certain desires, Lewis engages in special pleading, selecting evidence that aligns with his conclusion while ignoring counterexamples.

- Desires for transcendence may arise not from metaphysical truths but from existential fears, cognitive abstraction, or cultural narratives.

Symbolic Logic of Special Pleading:

- Let

represent the desire for transcendence.

- Let

,

, and

represent desires for wealth, power, and sexual relationships, respectively.

- Lewis asserts:

- He does not assert:

,

, or

.

Commentary:

Lewis’ exclusion of desires such as wealth () or power (

) reveals a selective methodology. If these desires are also innate and yet often unfulfilled, the universal premise (

) collapses.

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Desire falters due to its selective focus on desires that align with his theological framework while ignoring others. Universal human desires such as those for sexual partners, power, wealth, and fame are equally innate yet often go unfulfilled or result in dissatisfaction. These examples demonstrate that desires do not reliably correspond to external realities. Lewis’ selective methodology and special pleading undermine the argument’s logical foundation, making it an unpersuasive case for the existence of a transcendent reality.

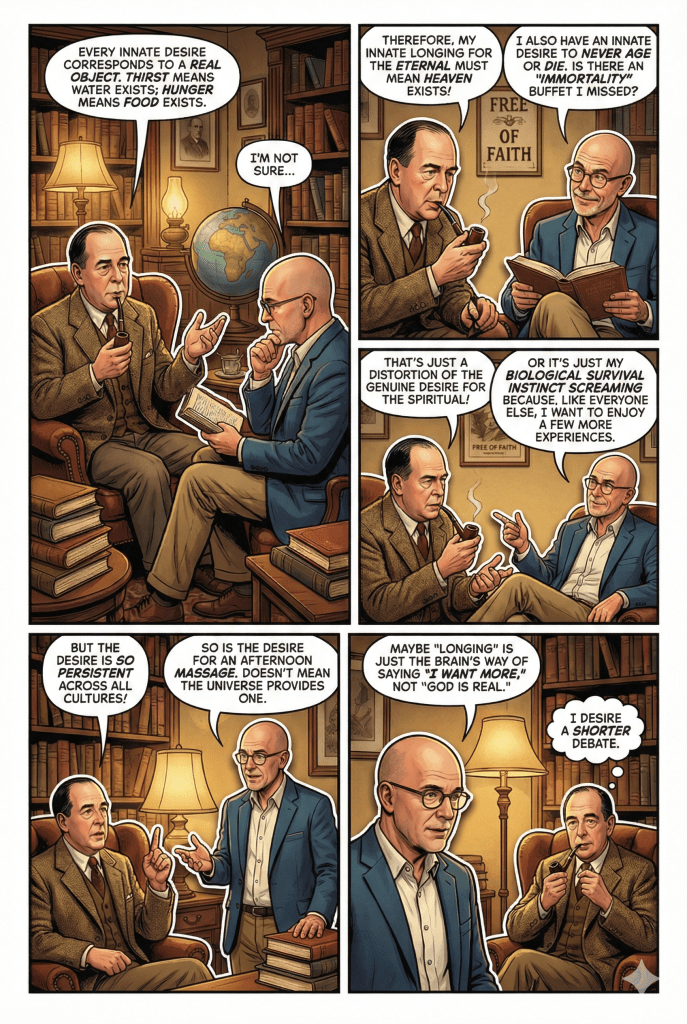

#1 — Dialogue: Lewis’ Argument from Innate Desires

Dialogue: C.S. Lewis and an Interlocutor on the Argument from Innate Desires

| C.S. Lewis | Interlocutor |

|---|---|

| It seems self-evident that every innate human desire corresponds to some real object. Hunger points to food, thirst to water, and tiredness to sleep. Why, then, would the human longing for transcendence and ultimate fulfillment not correspond to a real, transcendent reality—God? | That analogy works well for biological desires, but it doesn’t hold up for abstract or imaginative longings. For example, people have longed for immortality, utopia, or even the ability to fly, yet there’s no evidence that these correspond to real objects. Why should the longing for transcendence be any different? |

| But these longings—like immortality or utopia—often represent distortions of genuine desires. For example, the desire to fly could be seen as an exaggerated form of our need for freedom or exploration. The longing for transcendence, on the other hand, is universal and deeply rooted in the human experience, suggesting it corresponds to something real. | The universality of a longing doesn’t necessarily imply the reality of its object. Consider the widespread human desire for perfect justice. Despite its universality, there’s no evidence that perfect justice exists in any tangible or achievable form. Why should transcendence escape the same scrutiny? |

| That’s an interesting point, but universality is not the only evidence. The human longing for transcendence is distinct in that it isn’t simply wishful thinking or escapism. It arises from the profound sense that the material world cannot fully satisfy us. This dissatisfaction points us toward a higher, transcendent source. | That dissatisfaction might say more about human psychology than the existence of a transcendent reality. People’s dissatisfaction often stems from unmet expectations or emotional needs. Just because we feel unfulfilled by the material world doesn’t mean there’s a transcendent realm waiting to satisfy us. |

| Then how do you explain the depth and persistence of this longing? Surely its endurance across cultures and eras points to something more than mere emotional or social conditioning. If the longing for God were an illusion, wouldn’t it have faded away or become irrelevant over time? | Not necessarily. Persistent longings often reflect enduring psychological or evolutionary traits rather than external realities. For instance, humans have long desired immortality, yet this desire persists not because immortality exists, but because it’s a byproduct of our survival instinct and fear of death. The same could be true for the longing for transcendence. |

| But doesn’t this explanation reduce the richness and beauty of human experience to mere evolutionary mechanisms? Surely such an approach robs life of its meaning and fails to account for the profundity of aesthetic and spiritual experiences. | On the contrary, understanding the natural origins of our desires enriches our understanding of what it means to be human. The beauty and richness of life don’t require an external source for their value. We create meaning through our relationships, achievements, and experiences. The profundity you describe is a testament to human creativity and imagination, not necessarily evidence of God. |

| You’re assuming that meaning and value can be self-created, but if that’s true, how do we account for the longing for something eternal—something beyond the limits of human creativity? Surely our deepest desires point to a reality greater than ourselves. | We often long for things beyond our reach, but that doesn’t mean they exist. The desire for transcendence might simply reflect our awareness of limitations and mortality. It’s a powerful and meaningful aspect of being human, but it doesn’t require the existence of a transcendent source to make sense. |

| Then isn’t it bleak to conclude that our deepest desires might lead nowhere? Without God, what hope or purpose remains? | Not at all. The fact that we create our own meaning and purpose is empowering. It means we’re not dependent on external forces to live meaningful lives. Instead, we can find fulfillment in our finite existence, embracing the richness of the human condition without needing to project our desires onto the cosmos. |

/#2/ Lewis’ Argument from Morality

Challenging C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Morality

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Morality asserts that the existence of a universal and objective moral law implies the existence of a transcendent source—a moral Lawgiver, identified as God. While rhetorically compelling, this argument is deeply flawed. It assumes the existence of a monolithic morality across all cultures and neglects how simple emotions, shaped by evolution and social conditioning, ground altruistic behaviors and dispositions. This essay critiques the argument with rigorous syllogistic formulations and symbolic logic, demonstrating that Lewis’ premises are neither universally valid nor logically necessary.

Lewis’ Argument from Morality

C.S. Lewis argues that the existence of a universal and objective moral law points to a transcendent Lawgiver. His reasoning is summarized as follows:

- If there exists a universal and objective moral law, then it must originate from a transcendent Lawgiver.

- A universal and objective moral law exists, recognized across human societies.

- Therefore, a transcendent Lawgiver exists.

Symbolic Logic and Definitions

Symbols Defined

: Represents a universal and objective moral law.

: Represents a transcendent Lawgiver.

: Represents variations in moral behavior across cultures.

: Represents emotional or evolutionary grounding for behaviors.

Symbolic Logic

- Premise 1:

Annotation: If there exists a universal moral law, it must originate from a transcendent Lawgiver. - Premise 2:

Annotation: A universal and objective moral law exists. - Conclusion:

Annotation: Therefore, a transcendent Lawgiver exists.

Critique of Lewis’ Premises

Lewis’ argument rests on the assumption that a universal and objective moral law exists. However, examining cross-cultural examples demonstrates that behaviors often described as “moral” are better explained by emotional and social conditioning than by universal principles.

Critiquing the Universality of Morality

1. Killing in Self-Defense vs. Honor Killings

Example: In Western societies, killing in self-defense is widely accepted, while honor killings are condemned. In contrast, some traditional societies endorse honor killings as a means of preserving family reputation.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Premise 1: Human behaviors labeled as “moral” vary significantly between cultures (e.g., self-defense vs. honor killings).

- Premise 2: These behaviors are better explained by context-specific emotional responses, such as fear, anger, or shame, rather than by a universal moral law.

- Conclusion: Therefore, what is labeled “moral” reflects emotional and social conditioning, not a universal standard.

Symbolic Logic:

- Premise 1:

Annotation: There are variations in moral behavior across cultures. - Premise 2:

Annotation: Variations in behavior are grounded in emotional responses. - Conclusion:

Annotation: The variability in moral behavior contradicts the existence of a universal moral law.

Analysis: The emotional triggers—fear in self-defense and shame in honor killings—account for these behavioral differences, undermining Lewis’ claim of a universal standard.

2. Sharing Resources: Individualism vs. Collectivism

Example: Collectivist societies, such as traditional East Asian cultures, emphasize sharing resources as a duty to the community. Conversely, individualist cultures, like the United States, prioritize personal ownership and autonomy.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Premise 1: Behaviors like resource-sharing depend on cultural norms, which vary widely between collectivist and individualist societies.

- Premise 2: These norms are grounded in emotions like empathy, guilt, pride, or autonomy, not in a universal moral principle.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the variability of resource-sharing undermines the claim of a universal moral law.

Symbolic Logic:

- Premise 1:

Annotation: Cultural differences in moral behavior exist. - Premise 2:

Annotation: These differences are grounded in emotional responses. - Conclusion:

Annotation: The variability undermines the claim of a universal moral law.

Analysis: Social harmony is achieved differently depending on cultural priorities, reflecting emotional foundations rather than a universal standard.

3. Honesty: Pragmatism vs. Absolute Truth

Example: Western cultures often view honesty as a fundamental virtue, while many East Asian cultures prioritize harmony over truth, favoring “white lies” to avoid conflict.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Premise 1: Attitudes toward honesty vary by culture, with some valuing it as absolute and others treating it pragmatically.

- Premise 2: These attitudes stem from context-specific emotions, such as trust, guilt, empathy, or fear of conflict.

- Conclusion: Therefore, honesty is not governed by a universal moral law but by situational emotional factors.

Symbolic Logic:

- Premise 1:

Annotation: Variations in honesty exist across cultures. - Premise 2:

Annotation: These variations are grounded in emotional responses. - Conclusion:

Annotation: Honesty reflects emotional and cultural differences, not a universal standard.

Analysis: Honesty is applied differently depending on cultural and emotional contexts, contradicting the idea of a universal moral law.

4. Altruism as an Evolutionary Trait

Example: Behaviors like helping others or sharing resources can be explained as evolutionary adaptations that enhance group survival.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Premise 1: Altruistic behaviors promote group survival and are selected for through evolution.

- Premise 2: These behaviors do not require a transcendent source but arise naturally from evolutionary pressures.

- Conclusion: Therefore, altruistic behaviors do not depend on a universal moral law.

Symbolic Logic:

- Premise 1:

Annotation: Altruistic behaviors are explained by evolution. - Premise 2:

Annotation: Evolutionary origins negate the need for a universal moral law. - Conclusion:

Annotation: Altruism does not depend on a universal moral law.

Analysis: Evolutionary pressures explain altruism without invoking a transcendent or universal source.

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’ argument from morality hinges on the existence of a universal moral law () that necessitates a transcendent Lawgiver (

). However, cross-cultural examples demonstrate that moral behaviors vary widely and are better explained by emotional, social, and evolutionary factors (

). These critiques reveal that Lewis’ premises are not only unsupported but contradicted by evidence, dismantling the conclusion that a universal moral law exists or points to God. Would you like further refinements or expansions? C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Morality assumes the existence of a universal and objective moral law, but this premise collapses under scrutiny. Cross-cultural variations in behaviors, such as attitudes toward killing, sharing, honesty, and altruism, demonstrate that these behaviors are grounded in simple emotions shaped by evolutionary and social factors. Feelings of obligation, often cited as evidence for moral universality, are similarly explained by psychological conditioning. Therefore, the argument from morality fails to establish the existence of a universal moral law, let alone a transcendent Lawgiver.

Jack Johnston’s Response to C.S. Lewis’s Moral Argument

The Emotional Basis of Human Behavior Often Mistaken for Universal Morality

Human behaviors frequently described as reflections of a universal morality are better explained as manifestations of common human emotions and socially conditioned emotional values. These behaviors arise not from adherence to an objective moral standard but from the shared emotional landscape of humanity and the diverse ways in which communities prioritize and interpret these emotions. This essay demonstrates that both the commonality in human behaviors and their diversity are grounded in emotional dynamics rather than a universal moral framework.

The Commonality of Human Behaviors Explained by Shared Emotions

Human beings share a suite of emotions—such as empathy, fear, anger, guilt, and pride—that are biologically ingrained and evolutionarily advantageous. These shared emotions underpin many behaviors that are mistakenly attributed to universal moral principles.

1. Empathy Drives Cooperative Behavior

Empathy, the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, is a cornerstone of cooperative behavior. Humans universally exhibit behaviors such as helping those in distress or protecting vulnerable members of their communities. These actions are often labeled as moral but are better explained by empathy’s role in fostering group cohesion and survival.

Example:

- Behaviors like rescuing a drowning child or assisting an injured stranger transcend cultural boundaries. However, these actions arise not from an abstract moral principle but from the emotional discomfort of witnessing suffering and the empathetic desire to alleviate it.

Conclusion:

The ubiquity of empathetic behaviors across cultures reflects a common emotional capacity, not adherence to a universal moral standard.

2. Fear Regulates Harmful Actions

Fear, particularly the fear of retaliation or social exclusion, plays a critical role in discouraging behaviors that might harm others. Rules against theft, violence, and betrayal are often framed as moral universals but are grounded in the practical need to maintain safety and social harmony.

Example:

- Societies across the world condemn murder, but this consensus arises from the shared fear of living in a chaotic, unsafe environment rather than from an inherent moral truth.

Conclusion:

The avoidance of harm is an emotional response to fear, reinforced by practical considerations, not a reflection of a transcendent moral law.

3. Pride and Guilt Shape Altruistic Actions

Pride in fulfilling social expectations and guilt over violating them are powerful motivators of altruistic behavior. These emotions ensure that individuals align their actions with the values of their communities.

Example:

- In collectivist cultures, sharing resources with extended family elicits pride, while failing to do so brings guilt. In individualist societies, pride is tied to self-sufficiency, and guilt stems from perceived selfishness.

Conclusion:

The underlying emotional mechanisms of pride and guilt explain altruistic actions far more convincingly than an appeal to universal moral rules.

The Diversity of Human Behaviors Explained by Emotional Values

While certain emotions are common to all humans, how they are prioritized and expressed varies widely across cultures. This diversity accounts for the apparent contradictions in behaviors often labeled as moral.

1. Cultural Differences in Honesty

Honesty is praised in some cultures as a cardinal virtue, while others emphasize harmony over truthfulness, permitting or even encouraging “white lies” to maintain social peace.

Example:

- In Western societies, individuals are often praised for candidly expressing their thoughts, even if it causes discomfort. In contrast, East Asian cultures may prioritize avoiding conflict, viewing small untruths as necessary for preserving relationships.

Emotional Basis:

- Western Approach: Pride in authenticity and trustworthiness.

- East Asian Approach: Empathy for others’ feelings and fear of social discord.

Conclusion:

These differences are best explained by the emotional values each culture emphasizes, not by adherence to conflicting moral universals.

2. Approaches to Resource Sharing

Resource-sharing norms vary drastically between collectivist and individualist societies, reflecting different emotional priorities.

Example:

- Among hunter-gatherer groups, sharing resources is an expected behavior driven by compassion and reciprocity. Conversely, in capitalist societies, individual ownership is celebrated, and resource-sharing is often seen as charity rather than duty.

Emotional Basis:

- Collectivist Approach: Empathy for community members and fear of ostracism.

- Individualist Approach: Pride in self-reliance and guilt over perceived dependency.

Conclusion:

The diversity of sharing practices reflects community-specific emotional priorities rather than universal moral laws.

3. Variations in Justice Practices

Justice is another domain where cultural diversity challenges the idea of a universal moral standard. Some cultures prioritize retributive justice, while others emphasize reconciliation.

Example:

- In many tribal societies, acts of revenge are considered just and necessary to restore honor. In contrast, modern legal systems often focus on rehabilitation or restorative justice.

Emotional Basis:

- Retributive Approach: Anger and a desire for honor.

- Restorative Approach: Empathy for offenders and a hope for social harmony.

Conclusion:

These differences arise from contrasting emotional responses to conflict, not from fundamentally different moral codes.

The Emotional Grounding of Both Commonality and Diversity

The Common Thread: Universal Emotions

The shared emotional capacities of humans, such as empathy, fear, anger, and pride, account for the commonality of behaviors across cultures. These emotions naturally lead to behaviors that promote cooperation, reduce harm, and sustain social harmony—traits advantageous for survival.

The Divergence: Culturally Conditioned Values

Cultural diversity in behaviors arises from how societies prioritize and interpret these shared emotions. For example:

- Empathy: In one culture, it may prioritize family, while in another, it may extend to strangers.

- Fear: In one context, fear may discourage theft, while in another, it may enforce group loyalty.

These variations reflect the adaptability of emotional dispositions, not adherence to conflicting moral universals.

Conclusion

Human behaviors often labeled as moral are better understood as reflections of common human emotions and their culturally specific expressions. Both the commonality and diversity in these behaviors arise from shared emotional capacities and community-defined emotional values, rather than from a universal or transcendent moral standard. By grounding altruistic behaviors and social norms in emotions, we gain a more coherent and empirically supported understanding of human conduct—one that recognizes its deep emotional roots without invoking unnecessary metaphysical explanations.

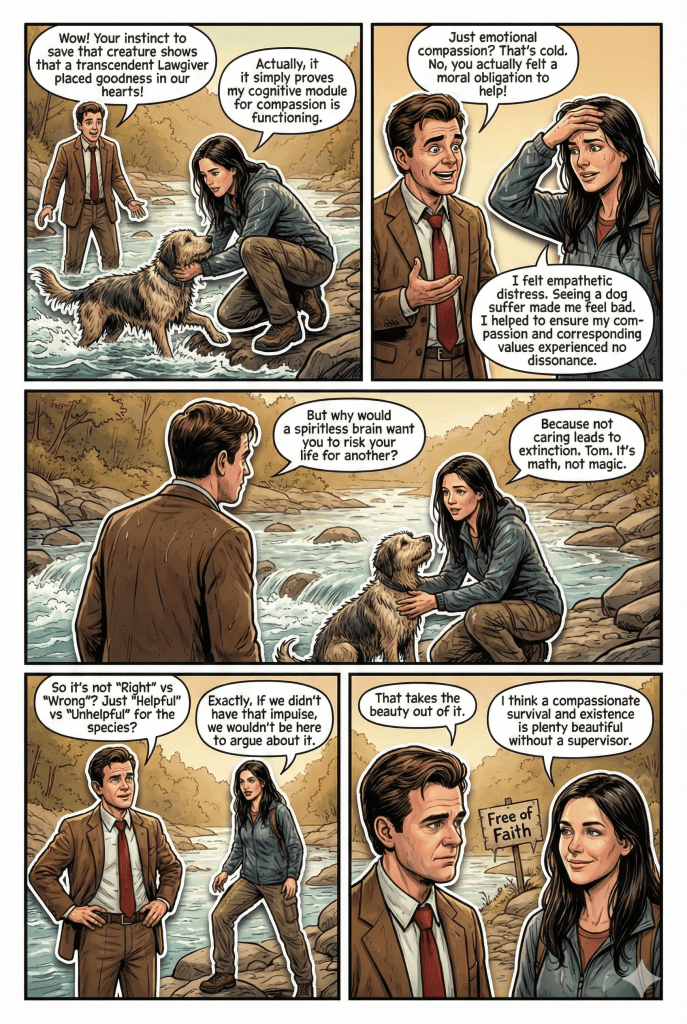

#2 — Dialogue: Lewis’ Argument from Morality

Dialogue: C.S. Lewis and an Interlocutor on the Argument from Morality

| C.S. Lewis | Interlocutor |

|---|---|

| It seems clear to me that without God, there is no grounding for objective moral values. If morality is purely subjective or culturally relative, we lose the foundation for declaring anything truly right or wrong. The existence of objective moral values and duties points directly to a moral Lawgiver—God. | I don’t think that follows. Morality doesn’t need a divine source to be objective. It can emerge from shared human experiences, logical consistency, and the requirements for social cooperation. Societies develop moral systems because they work, not necessarily because they’re dictated by a higher being. |

| But if morality arises only from social or evolutionary pressures, it becomes arbitrary. What’s right in one society could be wrong in another, and we’d have no grounds to condemn practices like slavery or genocide in other cultures. Only a transcendent moral law can provide the absolute standard we need. | I agree that morality varies between cultures, but that doesn’t mean it’s arbitrary. Human morality evolves as societies learn from experience. We condemn slavery and genocide today not because of divine revelation, but because we’ve developed empathy and rational principles like fairness and equality over time. Those principles arise naturally from human interaction, not from a divine command. |

| If morality is the result of human evolution, it’s still subjective, isn’t it? What one society sees as moral might contradict the values of another. Without a universal standard, how can we say that one culture’s morality is better or worse than another’s? | We can judge moral systems by their consequences—how well they promote well-being, reduce harm, and encourage cooperation. This doesn’t require a universal moral standard imposed by God, only shared human values and reasoning. For example, societies that reject slavery have thrived, while those that perpetuated it have faced significant internal conflict and collapse. |

| But consequences aren’t enough to ground morality. Without an absolute standard, morality becomes a matter of convenience rather than truth. For instance, if a society benefits from oppression, would that make oppression moral in that context? | Not at all. Oppression might benefit a select group temporarily, but it inevitably harms others and creates instability. Rationality and empathy allow us to see beyond immediate benefits to long-term consequences. Morality isn’t about convenience; it’s about principles that maximize well-being and fairness for all. |

| Yet rationality and empathy can differ from person to person, and even within a single society. Isn’t it dangerous to base morality on such shifting foundations? Only a divine moral Lawgiver can provide the unchanging standard we need to guide us. | I’d argue that unchanging standards are actually problematic because they fail to adapt to new knowledge and circumstances. Consider how religious texts condoned slavery or gender inequality in the past. Morality improves when it evolves alongside human understanding. A static, divine standard would freeze morality in time, making it less relevant to modern challenges. |

| Then what do you say about the human sense of moral obligation? People everywhere feel a deep sense of “oughtness,” even when it conflicts with their self-interest. Doesn’t this universal moral intuition point to something beyond human society? | Moral intuition is a product of evolution and social conditioning. It’s an adaptive mechanism that fosters cooperation and social harmony. Feeling a sense of “oughtness” doesn’t mean there’s a divine source behind it—it just means we’ve internalized norms that help us survive and thrive in groups. |

| But doesn’t this explanation strip morality of its depth and importance? If it’s all just evolution and social conditioning, where’s the meaning? | On the contrary, understanding morality’s origins enhances its importance. It shows us how deeply connected we are to one another and how much we depend on cooperation to flourish. Morality’s meaning comes from the role it plays in human life, not from a supposed divine origin. |

| The position of the editor is that of moral anti-realism. Comment on your interest in this position in the comments section if you’d like to explore or debate this. |

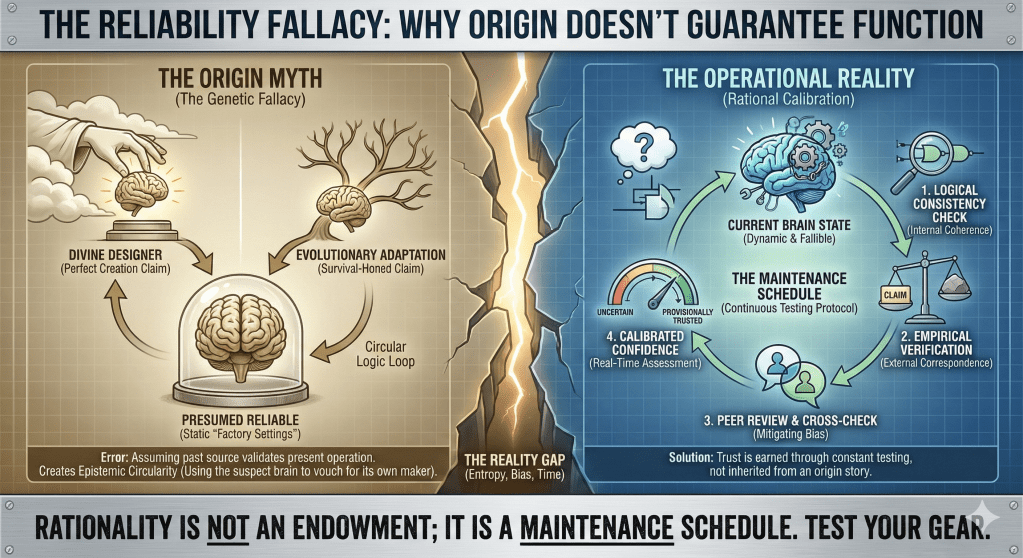

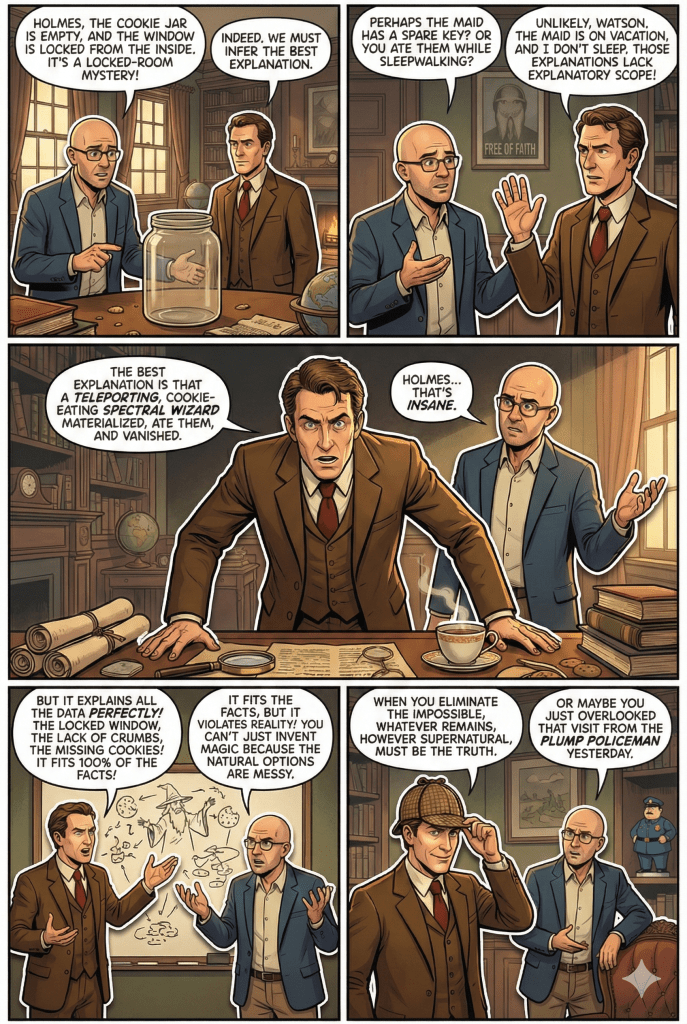

/#3/ Lewis’ Argument from Reason

Testing Reasoning Without Assuming Divine Origins

C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Reason posits that the reliability of human reasoning depends on its divine origin. He asserts that under naturalism, human reasoning, being a product of non-rational processes, would be untrustworthy. This argument, however, is both circular and inconsistent with how reasoning is tested in real-world contexts. Both Christians and non-Christians validate reasoning not by assuming it is divinely grounded but by testing it against reality. This essay will demonstrate, with robust examples and logical formulations, that the reliability of reasoning is grounded in its practical success and alignment with external reality, not in metaphysical assumptions.

1. Testing Reasoning in Education

Argument

Children do not assume their reasoning is divinely grounded when learning new concepts. Instead, they repeatedly test their reasoning against external standards, refining it through feedback and observation.

Example:

A child learning basic arithmetic initially might believe . Through correction and practice, they align their reasoning with consistent external results (e.g., counting objects or using a calculator).

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Reliable reasoning is validated through consistent alignment with observed results, not assumptions about its origin.

- Children test their reasoning through external feedback and correction.

- Therefore, reliable reasoning is established through practical testing, not assumptions of divine origin.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Let

represent testing reasoning against external reality.

- Let

represent the assumption of divine origin.

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

2. Testing Cognitive Decline in Old Age

Argument

Elderly individuals assess the reliability of their reasoning not by assuming divine origins but by comparing their cognitive performance to objective standards, such as memory tests or problem-solving exercises.

Example:

A senior citizen concerned about potential dementia might undergo a cognitive test administered by a doctor. The test evaluates their reasoning objectively, without invoking metaphysical claims about its source.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Reasoning reliability is assessed through observable performance, not assumptions about its origin.

- The elderly evaluate reasoning against objective criteria, not theological assumptions.

- Therefore, reasoning reliability is validated by its observable functionality, not divine origins.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Let

represent observable functionality.

- Let

represent the assumption of divine origin.

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

3. Testing Theories in Science

Argument

Scientists validate reasoning through empirical testing, reproducibility, and peer review. These methods rely on the practical success of reasoning, not its purported divine origin.

Example:

A physicist testing a new theory relies on experiments and data to confirm its validity. Reasoning is trusted to the extent that it produces reliable, repeatable results, not because of metaphysical assumptions about its source.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Reasoning is validated through empirical testing and reproducibility.

- Empirical testing evaluates reasoning based on its practical success, not assumptions about divine origins.

- Therefore, reasoning reliability is grounded in empirical validation, not metaphysical assumptions.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Let

represent empirical validation.

- Let

represent the assumption of divine origin.

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

4. Everyday Practical Decisions

Argument

In everyday life, reasoning is tested against reality through its success in achieving practical outcomes, not by assuming its divine origin.

Example:

A hiker navigating with a map tests their reasoning by comparing expected landmarks with observed landmarks. If their reasoning leads them astray, they adjust it based on reality.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Reasoning reliability is judged by its practical success in aligning with reality.

- Practical success does not require assumptions about divine origins.

- Therefore, reasoning reliability is established by its success, not metaphysical assumptions.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Let

represent practical success.

- Let

represent the assumption of divine origin.

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

5. The Circularity of Lewis’ Position

Lewis argues that human reasoning is reliable because it comes from God, and that God exists because human reasoning is reliable. This creates a circular problem:

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Human reasoning is reliable because it comes from God.

- We know God exists because human reasoning is reliable.

- Therefore, the argument assumes what it seeks to prove.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent the existence of God.

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

- Circularity: The reliability of reasoning (

) and the existence of God (

) depend on each other, making the argument question-begging.

6. The Wristwatch Analogy

Argument

The reliability of reasoning is like the functionality of a wristwatch: it must be tested directly against reality. Just as a watch’s accuracy is judged by comparing it to a reliable clock, reasoning is validated by its success in navigating the world, not by appealing to its origins.

Example:

If you find a watch in the forest, you don’t assume it works simply because it has a manufacturer. You test it by comparing its timekeeping to a known standard, such as the position of the sun or another clock.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Reliability is determined by comparison to external standards, not assumptions about origins.

- Reasoning, like a wristwatch, is validated through testing, not assumptions about its manufacturer.

- Therefore, reasoning reliability is established through testing, not metaphysical assumptions.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent reasoning as reliable.

- Let

represent testing against reality.

- Let

represent assumptions about origins (e.g., manufacturer).

- Premise 1:

- Premise 2:

- Conclusion:

Conclusion

Both Christians and non-Christians validate reasoning not by assuming its divine origin but by testing it against reality. Children refine their reasoning through education, the elderly assess cognitive health through external tests, and scientists evaluate reasoning through empirical methods. Practical success, not metaphysical assumptions, establishes reasoning’s reliability. C.S. Lewis’ argument is circular, as it assumes reasoning is reliable because of God and God exists because reasoning is reliable. Reasoning is better understood as a practical tool, validated like a wristwatch—through direct testing, not by appealing to its origins.

A Mind Awoken: Testing the Reliability of Reason After Memory Loss

Imagine a man waking up in an unfamiliar room after brain surgery. His memory is blank—he has no recollection of ever relying on his mind and no belief in a mind-creating God. He finds himself surrounded by basic household objects: a chair, a clock, a book, a ball, and a mirror. Stripped of assumptions about the reliability of his mind, he must use these items to test its functionality. His journey of discovery demonstrates how reasoning can be validated through interactions with reality, without invoking metaphysical beliefs.

1. Testing Consistency: The Ball and Gravity

The man notices a ball on the floor. He picks it up, holds it at chest height, and lets it go. The ball falls to the floor. He repeats the action several times, from different heights, observing the same result: the ball always falls downward.

Rationale:

By observing consistent outcomes, the man begins to form a rudimentary understanding of cause and effect. His reasoning aligns with external reality if he can predict that the ball will fall each time he lets it go.

Test:

- Drop the ball from different positions and heights.

- Predict its behavior and check if the prediction matches the outcome.

Conclusion:

Consistency in observed phenomena (e.g., the ball always falls) validates the mind’s ability to identify patterns and make reliable predictions.

2. Testing Perception: The Mirror

The man spots a mirror on the wall. He approaches it, startled to see his own reflection. He moves his hand, observing the reflected hand move in synchrony.

Rationale:

The mirror allows the man to test the accuracy of his sensory perception. If the image in the mirror behaves consistently with his movements, he can confirm that his visual and motor systems are in alignment.

Test:

- Wave a hand, tilt the head, and make facial expressions to see if the reflection behaves predictably.

Conclusion:

The mirror demonstrates that sensory input corresponds to external stimuli, strengthening confidence in the reliability of perception.

3. Testing Memory: The Chair Experiment

The man decides to test his memory. He places the chair in one corner of the room and walks away. After some time, he tries to recall where he placed the chair and walks back to check if his memory was correct.

Rationale:

Memory is an essential component of reliable reasoning. If he can consistently recall the chair’s location, it suggests that his mind retains information accurately over short periods.

Test:

- Place objects in specific locations, wait a while, and test the ability to recall their positions.

Conclusion:

Accurate recall of object locations validates the mind’s capacity for retaining and retrieving information.

4. Testing Problem-Solving: The Book and the Clock

The man notices a clock on the wall and a book on the table. The clock shows the time, but he wonders if it’s accurate. He decides to use the book, which includes a diagram of how the sun’s position correlates with the time of day, to verify the clock.

Rationale:

Using the book to interpret the position of the sun and comparing it to the clock’s reading tests the man’s ability to integrate information, reason logically, and evaluate the reliability of tools.

Test:

- Match the book’s diagram to the sun’s position and verify whether the clock shows the expected time.

Conclusion:

Successful problem-solving demonstrates that reasoning can synthesize information and produce accurate conclusions.

5. Testing Language and Communication: Naming Objects

The man begins naming the objects around him: “chair,” “ball,” “clock.” He uses these labels consistently as he interacts with them, forming connections between words and items.

Rationale:

Language allows the mind to organize thoughts and communicate ideas. If the man can consistently associate specific labels with objects, it confirms his ability to create and use a structured system of symbols.

Test:

- Assign names to objects and confirm that these names remain consistent in repeated interactions.

Conclusion:

Consistency in language use validates the mind’s capacity for structured, symbolic reasoning.

6. Testing Cause and Effect: The Door and the Doorknob

The man notices a door in the room and examines its knob. He pushes the door without turning the knob, and it doesn’t open. He then turns the knob and pushes again, and the door swings open.

Rationale:

This simple action tests his ability to infer cause and effect. Turning the knob changes the door’s state from locked to unlocked, demonstrating a direct relationship between action and outcome.

Test:

- Experiment with opening and closing the door using different methods to confirm the causal relationship.

Conclusion:

The ability to identify and replicate cause-and-effect relationships confirms the reliability of deductive reasoning.

7. Testing Logic: Sorting Objects

The man gathers the objects in the room and begins categorizing them. He places the chair and table in a group labeled “furniture” and the book and clock in a group labeled “tools.”

Rationale:

Sorting tests the ability to recognize shared characteristics and apply logical rules to create categories. Logical consistency is a fundamental aspect of reliable reasoning.

Test:

- Categorize objects based on observable traits and check for consistency in classification.

Conclusion:

Logical organization demonstrates the mind’s ability to process abstract relationships and maintain coherence in thought.

8. Testing Predictive Reasoning: Shadows and Light

The man observes sunlight streaming through a window and notices the movement of shadows. He predicts where the shadows will move as time passes and observes to see if his predictions are correct.

Rationale:

Predictive reasoning tests whether the mind can extrapolate patterns from observations. If his predictions about shadow movement are accurate, it validates his reasoning.

Test:

- Predict the future positions of shadows based on current observations and verify accuracy.

Conclusion:

Accurate predictions confirm the mind’s ability to project patterns into the future reliably.

9. Testing Error Correction: The Ball Again

The man picks up the ball again, but this time he predicts that if he throws it upward, it will remain in the air. When the ball falls back down, he realizes his prediction was wrong. He adjusts his reasoning, concluding that objects must fall due to some unseen force.

Rationale:

Error correction is a hallmark of reliable reasoning. The ability to recognize mistakes and refine understanding ensures adaptability.

Test:

- Form hypotheses, test them, and refine them based on observed outcomes.

Conclusion:

The iterative process of hypothesis testing and error correction demonstrates the self-improving nature of reasoning.

10. Reflecting on Reasoning: Meta-Cognition

Finally, the man sits down and reflects on his thought process. He considers whether his conclusions about the room and its objects align with his observations.

Rationale:

Meta-cognition—thinking about thinking—allows the mind to evaluate its own reliability. This reflective process provides a feedback loop for improving reasoning.

Test:

- Review the steps taken to test reasoning and check for consistency and coherence.

Conclusion:

The ability to evaluate one’s own reasoning confirms the mind’s capacity for self-correction and improvement.

Conclusion

The man in the room validates the reliability of his mind not through metaphysical assumptions but through direct, practical engagement with reality. By testing perception, memory, logic, and problem-solving, he demonstrates that reasoning can be self-validating. This process resembles testing a wristwatch against observable phenomena: its reliability is judged by its functionality, not by appealing to its manufacturer. Reasoning, like the man’s mind, is best understood as a tool that proves its worth through use, adaptation, and alignment with reality.

In-Depth Analysis of C.S. Lewis’ Argument from Reason

C.S. Lewis’ argument asserts that the reliability of human reasoning can only be grounded in the presupposition of a reliable God. According to Lewis, if human cognition arises from blind, unguided natural processes, it cannot reliably lead to truth. This claim raises several philosophical issues, particularly regarding circular reasoning, empirical justification, and alternative naturalistic explanations. Below, we will provide an in-depth analysis and critique of Lewis’ argument, using symbolic logic to clarify and evaluate the premises and conclusions.

1. The Core Argument: Reason Requires a Reliable God

Lewis’ Argument

- Premise 1: If human reasoning is reliable, it must be grounded in a rational and reliable God.

- Premise 2: Human reasoning is reliable.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a rational and reliable God exists.

Symbolic Logic

- Definitions:

: Human reasoning is reliable.

: A rational and reliable God exists.

- Lewis’ Argument in Symbolic Form:

Annotation: If human reasoning is reliable, it must be grounded in God.

Annotation: Human reasoning is reliable.

Annotation: Therefore, God exists.

Critique of Lewis’ Argument

- Circular Reasoning: The argument presupposes the existence of a reliable God (

) to justify the reliability of reasoning (

). This creates a circular dependency, as the conclusion (

) is embedded in the premise (

).

- Lack of Empirical Evidence: The assumption that reasoning must be grounded in God lacks empirical support. Cognitive science and evolutionary biology provide naturalistic explanations for reasoning abilities (

).

- Alternative Explanations: Reliable reasoning can emerge through natural selection, where accurate perception and reasoning confer survival advantages. Thus,

does not necessarily imply

.

2. Rebuttal: Christians Do Not Rely on This Argument

Even Christians do not practically rely on Lewis’ grounding argument for their confidence in reasoning. Instead, Christians assess the reliability of their reasoning through testing, practice, and empirical feedback, much like non-Christians.

Counterargument

- Premise 1: If Christians rely on the belief in God as the sole basis for rationality, they would not engage in empirical testing of their reasoning.

- Premise 2: Christians frequently test their reasoning through empirical methods (e.g., education, discussion, cognitive exercises).

- Conclusion: Therefore, Christians do not rely solely on their belief in God to ground the reliability of reasoning.

Symbolic Logic

- Definitions:

: Christians believe in God as the sole basis for rationality.

: Christians test their reasoning empirically.

- Phil’s Argument in Symbolic Form:

Annotation: If Christians rely solely on God for rationality, they would not test their reasoning empirically.

Annotation: Christians test their reasoning empirically.

Annotation: Therefore, Christians do not rely solely on God to ground rationality.

Analysis

The counterargument demonstrates that Christians, like non-Christians, rely on empirical methods to evaluate and hone their reasoning. This undermines Lewis’ claim that belief in God is the sole or necessary foundation for reliable cognition.

3. The Alternative Explanation: Naturalistic Evolution

A naturalistic explanation for reasoning posits that reliable cognition evolved as an adaptive trait. Accurate reasoning and perception increase an organism’s chances of survival and reproduction, providing a clear natural mechanism for the development of reliable cognitive faculties.

Naturalistic Argument

- Premise 1: Reliable reasoning enhances survival and reproductive success.

- Premise 2: Evolution selects for traits that enhance survival and reproduction.

- Conclusion: Therefore, reliable reasoning is an expected product of natural evolution.

Symbolic Logic

- Definitions:

: Human reasoning is reliable.

: Reliable reasoning evolves through natural selection.

- Naturalistic Argument in Symbolic Form:

Annotation: If reasoning evolves through natural selection, it is likely to be reliable.

Annotation: Reliable reasoning evolves through natural selection.

Annotation: Therefore, human reasoning is reliable.

Analysis

This explanation avoids the circular reasoning inherent in Lewis’ argument and provides empirical support through evolutionary theory and cognitive science. Reliable reasoning can emerge naturally without invoking God.

4. Circular Reasoning in Lewis’ Argument

Lewis’ argument presupposes the reliability of human reasoning to construct and evaluate the premises of his argument. If human reasoning is unreliable without God, then Lewis cannot use reasoning to establish God’s existence without assuming his conclusion.

Symbolic Logic of Circularity

- Definitions:

: Human reasoning is reliable.

: A rational and reliable God exists.

- Circular Dependency:

Annotation: Reliable reasoning requires God.

Annotation: Reasoning is reliable (assumed to construct the argument).

Annotation: God exists, based on the reliability of reasoning.

- Circularity: The conclusion (

) is embedded in the premise (

), making the argument logically invalid.

5. Broader Epistemological Critiques

Alternative Epistemologies

- Empiricism: Knowledge is grounded in sensory experience and observation, not in a presupposed deity.

- Coherence Theory: Knowledge is justified through the internal consistency of beliefs.

- Pragmatism: The reliability of reasoning is assessed based on its practical success in navigating the world.

Symbolic Logic for Non-Theistic Grounds

- Definitions:

: Pragmatic success.

: Coherent belief system.

: Reliable reasoning.

Annotation: Pragmatic success implies reliable reasoning.

Annotation: Coherent beliefs imply reliable reasoning.

These frameworks demonstrate that reliable reasoning does not require God ().

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’ argument that reliable reasoning must be grounded in God is undermined by logical weaknesses, including circular reasoning and a lack of empirical support. Phil’s rebuttal demonstrates that even Christians do not rely on Lewis’ argument to assess their rationality, instead testing their reasoning empirically like anyone else. Furthermore, naturalistic explanations, grounded in evolution and alternative epistemologies, provide robust frameworks for understanding the reliability of reasoning without invoking a deity. This comprehensive critique reveals that Lewis’ argument is both unnecessary and invalid as a foundation for rationality. Would you like to refine or expand on any specific section?

See also:

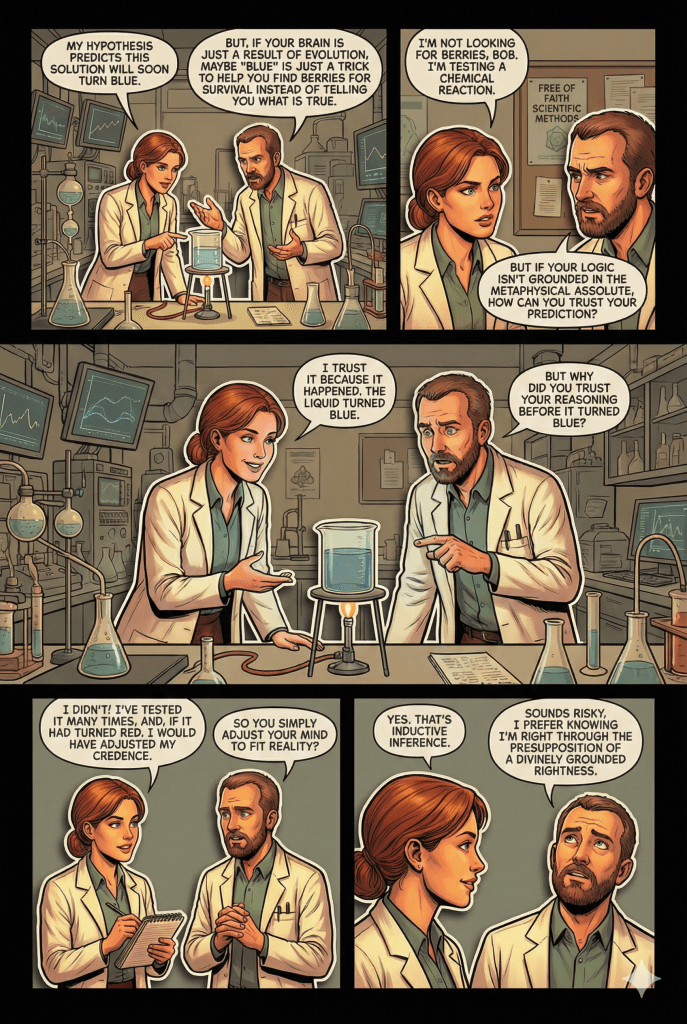

#3 — Dialogue: Lewis’ Argument from Reason

Dialogue: C.S. Lewis and an Interlocutor on the Argument from Reason

| C.S. Lewis | Interlocutor |

|---|---|

| If our reasoning is the result of blind, unguided natural processes, then we have no reason to trust it. Why should random evolutionary mechanisms produce reliable faculties for discovering truth? Our ability to reason must come from a rational, trustworthy source—namely, God. | That assumes evolution is random in its outcomes, which isn’t accurate. Evolution favors traits that enhance survival and reproduction. Reliable reasoning would have clear survival advantages, such as accurately identifying threats or solving problems, which makes it an expected result of evolution, not a random occurrence. |

| But evolution only selects for survival, not truth. What’s useful for survival might not align with what is true. For example, an illusion might help an organism survive better than the truth. If naturalism is true, there’s no guarantee that our reasoning leads to truth, only to survival. | That distinction isn’t as sharp as you suggest. Survival often depends on accurately perceiving and understanding reality. For instance, recognizing a predator correctly or understanding cause and effect in the environment increases an organism’s chances of survival. Thus, evolution selects for faculties that are at least approximately reliable in tracking truth. |

| Even if evolution produces reliable reasoning for survival, it doesn’t explain why we trust abstract reasoning, like mathematics or logic. These don’t have direct survival value, yet they work remarkably well for understanding the universe. Isn’t it more reasonable to believe that a rational God designed our minds to grasp these truths? | Abstract reasoning could still have evolutionary origins. For example, early humans who could plan ahead or understand patterns likely had a survival advantage. Over time, these cognitive tools were refined and applied to abstract domains like mathematics and logic. Their success in describing the universe reflects the human ability to generalize and adapt, not necessarily the existence of a divine designer. |

| But how do you account for the trustworthiness of reason itself? If naturalism is true, reason is just a byproduct of chemical reactions in the brain. Why should we trust such processes to deliver truth? | Trust in reason comes from its demonstrated reliability, not from presupposing a divine source. We test our reasoning constantly—through experiments, discussions, and real-world applications. The fact that reason works is enough to justify using it, regardless of its origins. |

| Yet by testing reason, aren’t you assuming its reliability? That’s circular. You’re using reason to prove reason, which means you can’t ultimately justify it without appealing to something greater, like God. | The same critique applies to your argument. You assume reason is reliable to argue for God’s existence, which also uses reason to prove reason. The difference is that I don’t need an external justification for reason—it works, and its success in explaining and predicting the world is its own validation. |

| But without grounding reason in something transcendent, isn’t it arbitrary? If it’s just the result of evolutionary processes, it seems like an accident rather than something we can truly trust. | It’s not arbitrary—it’s adaptive. Evolution selects for reasoning because it enhances survival. Far from being an accident, it’s a deeply ingrained trait that reflects its usefulness. Trusting reason because it works is more practical and evidence-based than assuming it requires a divine source. |

| So, you’re saying that the reliability of reason can be explained purely through naturalistic processes? Doesn’t that strip reason of its deeper meaning and purpose? | Not at all. Understanding that reason evolved naturally doesn’t diminish its value—it shows how remarkable and adaptive the human mind is. The meaning and purpose of reason come from how we use it to navigate and understand the world, not from presuming it was gifted to us by a deity. |

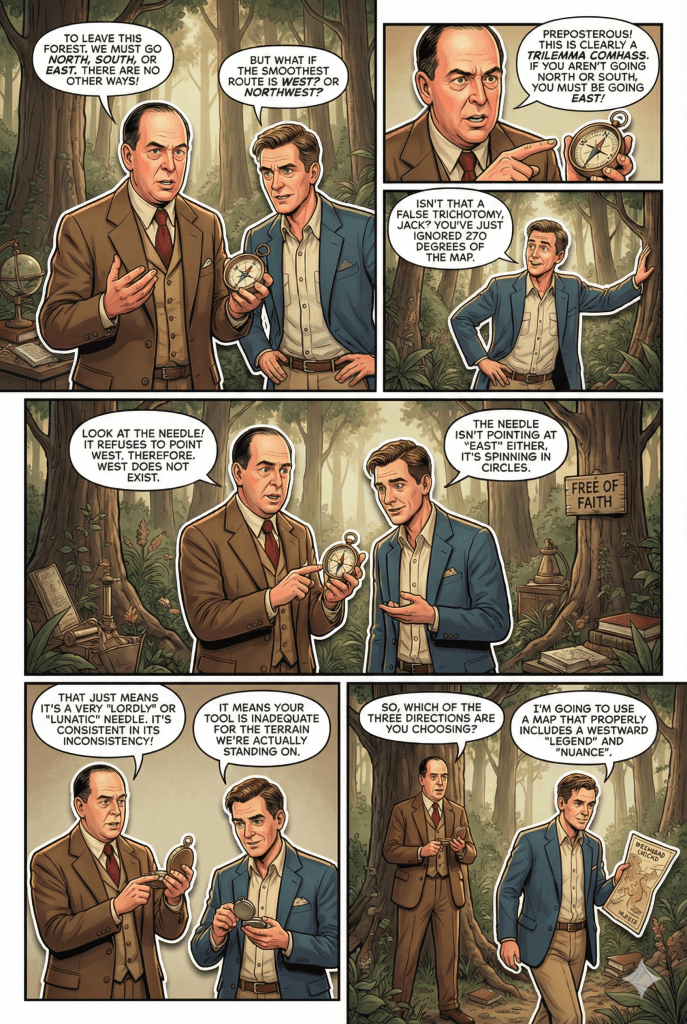

/#4/ Lewis’ Trilemma Argument

The Multifaceted Jesus: A Reflection of the Trilemma (+1) Categories

C.S. Lewis’ Trilemma argues that Jesus must be either a liar, a lunatic, or Lord. However, this oversimplification neglects the complexities of human behavior and history. Jesus likely embodied qualities of all four categories—liar, lunatic, Lord, and legend—to varying degrees. This essay argues that Jesus’ life and legacy reflect a mixture of these elements, using logical formulations with explanatory commentary to illustrate how this nuanced view resolves the shortcomings of the Trilemma.

1. Jesus as a Partial Liar

Argument

Jesus may have exaggerated or strategically allowed misunderstandings about his divinity to persist, using hyperbole or ambiguous claims to inspire followers and reinforce his mission. Such actions could reflect partial dishonesty without negating his sincerity in other areas.

Examples:

- Allowing followers to interpret him as divine while emphasizing his unique relationship with God.

- Using rhetorical devices to highlight his message, such as predicting apocalyptic events (Mark 13:30).

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Exaggerations or strategic misstatements do not negate sincerity in one’s overall mission.

- Jesus might have used exaggerations to inspire or solidify his authority.

- Therefore, Jesus could be partly a liar without being fully deceitful.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent Jesus as a liar.

- Let

represent exaggerations or strategic misstatements.

- Premise 1:

- Commentary: This means that instances of exaggeration or misrepresentation support the idea that Jesus exhibited some degree of dishonesty.

- Premise 2:

- Commentary: Exaggeration combined with sincerity (e.g., believing in the overall mission) implies that Jesus was not a continuous or wholly deceitful liar.

- Conclusion:

- Commentary: The conclusion shows that Jesus may have been partially a liar without his entire mission being based on dishonesty.

2. Jesus as a Partial Lunatic

Argument

Jesus may have sincerely believed in his divine mission or unique connection to God, even if such beliefs were partially delusional or exaggerated. Religious conviction often involves blending genuine insight with overconfidence.

Examples:

- Believing he fulfilled Jewish prophecy, even if the belief was exaggerated.

- Claiming unity with God in a way that reflected profound conviction rather than literal truth.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Sincere beliefs can coexist with partial delusions.

- Jesus might have held sincere but exaggerated beliefs about his divine mission.

- Therefore, Jesus could be partly a lunatic without being fully delusional.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent Jesus as a lunatic.

- Let

represent sincerity of belief.

- Premise 1:

- Commentary: Sincerity combined with some degree of delusion supports the possibility of partial lunacy.

- Premise 2:

- Commentary: Lunacy need not be absolute; Jesus could be mistaken about certain aspects of his mission while retaining clear thinking in others.

- Conclusion:

- Commentary: The conclusion shows that partial lunacy does not disqualify Jesus from having profound moral conviction.

3. Jesus as Partially Lord

Argument

Despite potential exaggerations and delusions, Jesus’ teachings reflect profound moral and spiritual wisdom. His ethical insights and leadership demonstrate genuine authority, aligning with the concept of partial Lordship.

Examples:

- Ethical teachings such as “Love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44) reflect deep moral insight.

- The loyalty and transformation inspired among his followers indicate his spiritual leadership.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Profound moral insight indicates partial spiritual authority.

- Jesus’ teachings reflect wisdom and leadership that align with partial lordship.

- Therefore, Jesus could be partly Lord without literal divinity.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent Jesus as Lord.

- Let

represent wisdom and moral insight.

- Premise 1:

- Commentary: Demonstrating wisdom and moral insight suggests that Jesus had partial authority as a spiritual leader.

- Premise 2:

- Commentary: Being “Lord” in this sense does not require literal divinity, only moral and spiritual leadership.

- Conclusion:

- Commentary: The conclusion confirms that Jesus’ teachings and leadership justify partial lordship.

4. Jesus as Partially Legend

Argument

The Gospel accounts, written decades after Jesus’ death, reflect layers of embellishment and theological interpretation. These legendary elements coexist with historical truths, creating a partial legend.

Examples:

- Stories like walking on water or feeding thousands could be later additions meant to emphasize Jesus’ divine status.

- Selective memory and theological priorities shaped how Jesus’ life was recorded.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Oral traditions often evolve, incorporating embellishments and interpretations.

- The Gospel accounts likely reflect both historical events and legendary elements.

- Therefore, Jesus could be partly legend without being fully fabricated.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent Jesus as a legend.

- Let

represent oral tradition shaping accounts.

- Premise 1:

- Commentary: The influence of oral tradition suggests that legendary elements naturally arose in the Gospel accounts.

- Premise 2:

- Commentary: Legendary elements do not imply that the entire story of Jesus is false.

- Conclusion:

- Commentary: The conclusion acknowledges the coexistence of historical and legendary elements in Jesus’ narrative.

5. Integrating the Four Categories

Argument

Jesus’ life likely reflected a mixture of all four categories, blending sincerity, exaggeration, delusion, profound wisdom, and later mythologizing. This view resolves the rigidity of Lewis’ Trilemma and aligns with the complexities of human nature.

Syllogistic Formulation:

- Human beings exhibit complex and multifaceted traits.

- Jesus could have simultaneously displayed qualities of liar, lunatic, Lord, and legend to varying degrees.

- Therefore, Jesus’ identity cannot be reduced to a trilemma but must be understood as a blend of these categories.

Symbolic Logic:

- Let

represent Jesus as a mixture of categories.

- Premise 1:

- Commentary: The presence of any combination of the four categories supports the idea of Jesus as a complex figure.

- Premise 2:

- Commentary: Each category contributes to understanding Jesus’ identity in degrees, rather than as absolutes.

- Conclusion:

- Commentary: The conclusion integrates all four categories into a coherent, multifaceted understanding of Jesus.

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’ Trilemma oversimplifies the complexities of Jesus’ life and legacy. A nuanced perspective reveals that Jesus likely embodied elements of all four categories—liar, lunatic, Lord, and legend—to varying degrees. This multifaceted view accounts for his profound moral teachings, possible exaggerations, sincere but potentially delusional beliefs, and the mythologizing of his story over time. By recognizing this complexity, we move beyond rigid frameworks to appreciate Jesus as a deeply human figure whose legacy has inspired countless interpretations. This richer understanding aligns with human nature and the dynamics of history, making Jesus more relatable and impactful.

A More Rigorous Examination of Lewis’ Trilemma

C.S. Lewis’ Trilemma asserts that Jesus must be either a liar, a lunatic, or the Lord, based on his claims of divinity. This argument assumes exhaustive and mutually exclusive categories and rests on several unstated premises that do not withstand rigorous logical scrutiny. Below is a step-by-step symbolic logic refutation that dismantles the Trilemma.

Definitions and Symbols

Let:

: Jesus existed as a historical figure.

: Jesus claimed divinity.

: Jesus was a liar (knowingly made false claims about divinity).

: Jesus was a lunatic (sincerely believed false claims about divinity due to delusion).

: Jesus was Lord (his claims of divinity were true).

: Jesus’ claims or depictions were partly or wholly legendary (i.e., misattributions, exaggerations, or fabrications by followers).

: Jesus represents a mix of two or more categories (e.g., partial liar, partial lunatic, partial legend).

Step 1: Lewis’ Trilemma in Symbolic Form

Lewis claims:

- If

and

, then

.

- Natural language annotation: If Jesus existed and claimed divinity, then he must be a liar, a lunatic, or Lord.

.

- Natural language annotation: Jesus was neither a liar nor a lunatic.

- Therefore,

.

- Natural language annotation: Jesus must be Lord.

Step 2: Adding Legend and Mixed Categories

Lewis’ trilemma assumes three mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories. However, this assumption neglects:

- Legendary accounts (

): The possibility that claims attributed to Jesus were embellished or fabricated.

- Mixed traits (

): The possibility that Jesus exhibited qualities of multiple categories (e.g., partial liar, partial lunatic).

To account for these possibilities:

.

- Natural language annotation: Jesus must belong to at least one of five categories: liar, lunatic, Lord, legend, or a mix.

Step 3: Contradicting the Exclusivity of the Trilemma

1. Overlapping Categories

The categories ,

, and

are not mutually exclusive:

- A person can be partly a liar and partly delusional (

).

- Natural language annotation: Jesus might have sincerely believed in his mission but exaggerated or misrepresented aspects of it.

- A person can inspire legendary accounts (

) while still being partly truthful or delusional.

- Natural language annotation: Jesus might have existed and made claims that were later embellished by followers.

2. Exhaustiveness Violated

Lewis’ trilemma fails to consider and

, invalidating its claim to exhaustiveness:

does not account for:

- Embellishments (

).

- Mixed categories (

).

- Embellishments (

Revised Logical Space:

- Natural language annotation: The addition of legend and mixed categories refutes the completeness of the Trilemma.

Step 4: Refuting Specific Claims

1. Refuting

Lewis claims Jesus was not a liar because of his moral teachings:

- Natural language annotation: Jesus could be partly a liar if he knowingly exaggerated claims, even if sincere about other aspects of his mission.

- Evidence for

: Ambiguous or exaggerated claims, such as apocalyptic predictions (Mark 13:30), suggest possible strategic misrepresentation.

2. Refuting

Lewis claims Jesus was not a lunatic because his teachings were rational:

- Natural language annotation: Jesus could exhibit partial lunacy if his self-perception included delusions.

- Evidence for

: Claims of being “one with God” (John 10:30) might reflect genuine conviction rather than literal truth.

3. Refuting

Lewis concludes that Jesus must be Lord. However:

Jesus’ claims about divinity are literally true

- Natural language annotation: The burden of proof lies on establishing the literal truth of divinity claims.

- Evidence against

: The reliance on Gospel accounts, written decades later, undermines the certainty of this claim.

4. Affirming

Jesus’ life and teachings were embellished by followers.

- Natural language annotation: Oral traditions and theological agendas likely contributed to legendary elements in the Gospel accounts.

- Evidence for

: Stories like walking on water or the virgin birth align with common mythologizing patterns in religious traditions.

Step 5: Formal Refutation of Lewis’ Trilemma

1. Trilemma’s Claim:

- Natural language annotation: If Jesus existed and claimed divinity, he must be liar, lunatic, or Lord.

2. Refutation:

- Natural language annotation: Jesus could be liar, lunatic, Lord, legend, or a mix.

- Natural language annotation: The inclusion of legend and mixed categories invalidates the Trilemma’s claim to completeness.

Conclusion

C.S. Lewis’ Trilemma fails because it assumes three mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories while ignoring the possibilities of partial traits () and legendary embellishments (

). A rigorous symbolic analysis demonstrates that Jesus’ identity cannot be reduced to liar, lunatic, or Lord. Instead, a nuanced view accounts for the complexity of historical figures and the evolution of narratives over time. By failing to consider these dimensions, the Trilemma collapses under logical scrutiny.

#4 — Dialogue: Lewis’ Trilemma Argument

Dialogue: C.S. Lewis and an Interlocutor on the Trilemma Argument (Liar, Lunatic, or Lord)

| C.S. Lewis | Interlocutor |

|---|---|

| Jesus made claims about His divinity that leave us with only three logical possibilities: He was either lying, deluded, or telling the truth. A man who claims to be God is either a deceiver, a lunatic, or truly the Lord. Given the profound wisdom and moral character of Jesus, it seems absurd to label Him as a liar or a lunatic. Therefore, He must be Lord. | Your trilemma assumes there are only three options, but that’s a false trichotomy. A fourth possibility is that Jesus’ divine claims were exaggerated or misinterpreted over time—what we might call the “legend” hypothesis. The Gospels were written decades after Jesus’ death, in a context where oral traditions often transformed stories significantly. |

| The “legend” hypothesis doesn’t hold up when we consider the historical reliability of the Gospels. These texts were written by those who knew Jesus or their close associates, and their accounts are remarkably consistent. If Jesus never claimed divinity, how do you explain the early Church’s belief in His divinity, even to the point of enduring persecution and martyrdom? | Even reliable texts can exaggerate or mythologize key figures over time. The belief in Jesus’ divinity could have emerged from His followers’ reverence for Him, amplified by cultural expectations of messianic figures. Persecution doesn’t prove the truth of a belief—it only demonstrates the depth of conviction, which we see in other religions too, like Islam or Mormonism. |