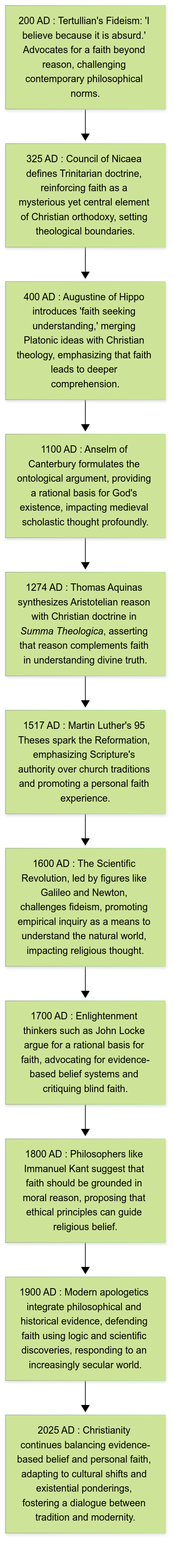

The chart below provides a rough depiction of the evolution of the notion of proper redemptive belief within Christendom over the centuries.

The Evolution of Redemptive Faith Over Time

The chart above roughly depicts the changing perspectives within Christianity regarding the relationship between faith and evidence from 200 AD to 2025 AD. It focuses on four categories of belief: Fideism, Full belief with partial evidence, Non-rigorous belief, and Rigorous evidence-based belief. Each era reflects how prominent events and theological leaders influenced the understanding of faith necessary for salvation.

Note the movement away from Fideism toward Evidentialism. This evolution in Christian thought was driven by a series of intellectual, theological, and cultural developments. In the early Church, faith was primarily seen as an unquestioning trust in divine revelation, with figures like Tertullian promoting the idea that belief in God transcends rational understanding. This perspective was reinforced by Church councils and doctrines that emphasized the mystery of divine truths. However, the integration of Greek philosophy, especially through thinkers like Augustine and later Thomas Aquinas, initiated a gradual shift. Augustine’s famous phrase, “I believe in order to understand,” illustrated the early acknowledgment that reason could support faith rather than oppose it.

The Reformation accelerated this movement by emphasizing the evidential authority of Scripture. Reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin rejected the Church’s reliance on tradition alone, arguing instead that faith should be grounded in the clear teachings of the Bible. Concurrently, the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment challenged fideistic perspectives by promoting empirical observation and rational inquiry as the primary paths to truth. Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant redefined faith to be in harmony with reason, insisting that religious beliefs must be supported by moral or historical evidence. By the 19th and 20th centuries, Christian apologetics, led by figures such as William Paley and William Lane Craig, increasingly emphasized the compatibility of faith and evidence, paving the way for modern evidentialism in religious thought.

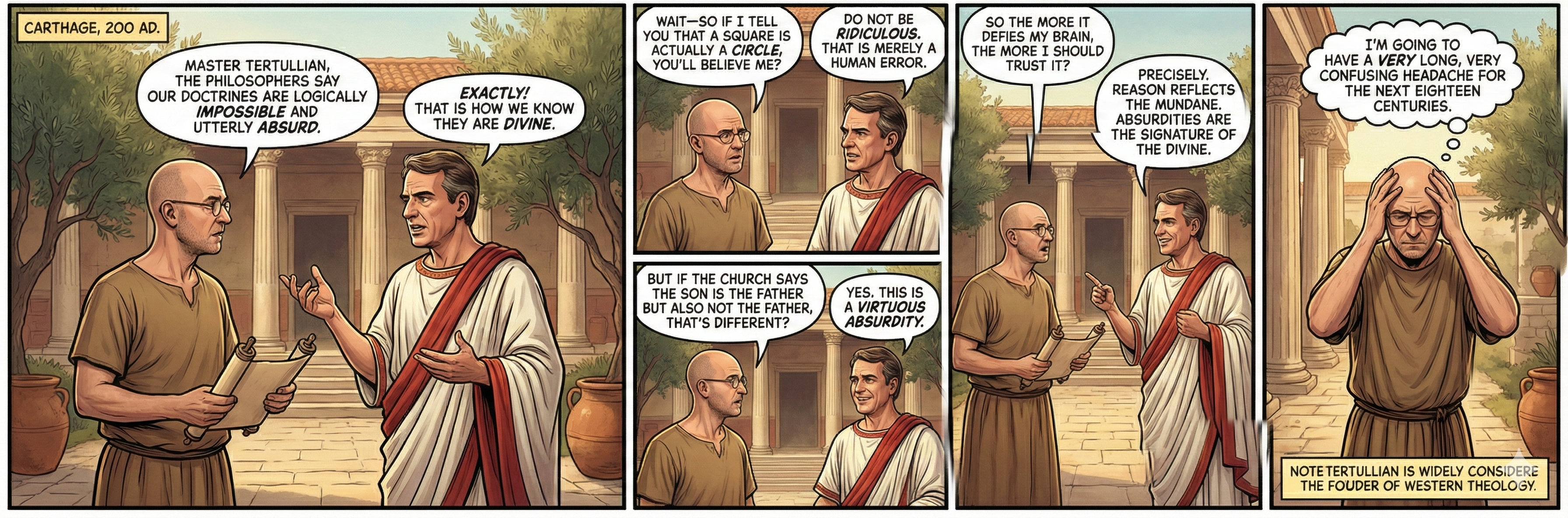

200 AD to 600 AD: The Early Church and the Primacy of Fideism

In the early centuries of Christianity, Fideism, the belief in redemption through faith without reliance on evidence, was the prevailing view. Early Christian leaders emphasized that faith transcended human reason. Tertullian (c. 160–225 AD) famously stated, “I believe because it is absurd” (“Credo quia absurdum est”), suggesting that the mysteries of God defy human comprehension.

During this time, Irenaeus of Lyons emphasized the authority of divine revelation, arguing in Against Heresies:

“If we cannot discover explanations of all things in Scripture, let us not seek out others besides God… The Scriptures are perfect, since they were spoken by the Word of God and His Spirit.”

The Council of Nicaea (325 AD) established the doctrine of the Trinity, reinforcing that faith in core mysteries was to be accepted based on Church authority, not rational inquiry. However, figures like Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD) began integrating reason with faith. In his work De Doctrina Christiana, Augustine wrote:

“Understanding is the reward of faith. Therefore, seek not to understand that you may believe, but believe that you may understand.”

Thus, by 600 AD, partial evidence-based faith was slowly growing as theologians engaged with classical philosophy.

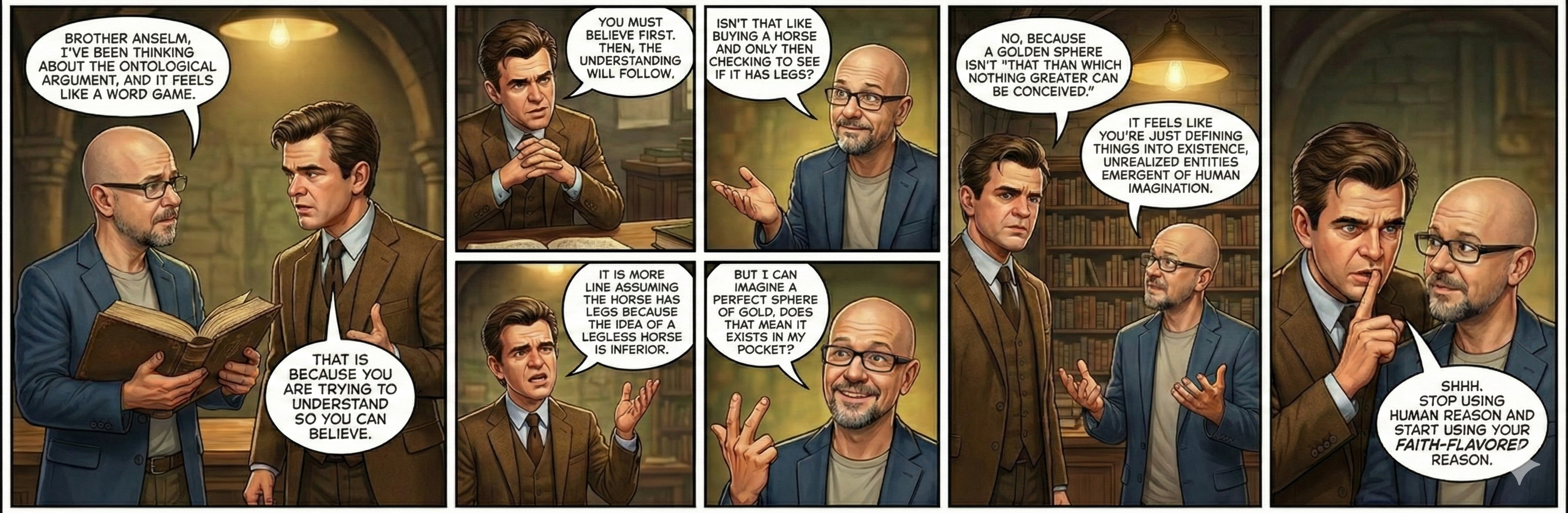

800 AD to 1200 AD: The Rise of Scholasticism

Between 800 and 1200 AD, Scholasticism emerged, driven by theologians such as Anselm of Canterbury and Thomas Aquinas. Anselm’s famous Proslogion introduced the ontological argument for God’s existence, asserting that belief in God could be supported through rational proof:

“Faith seeks understanding. I do not seek to understand that I may believe, but I believe in order to understand.”

Despite this shift, Fideism remained influential, particularly within mystical traditions. Scholastics sought to harmonize faith and reason, laying the groundwork for full belief with partial evidence.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), in Summa Theologica, advanced this synthesis, stating:

“Reason in man is rather like God in the world.”

He argued that although divine truths exceed reason, they do not contradict it. By the 1200s, non-rigorous belief gained traction as rational explanations were seen as complementary to faith.

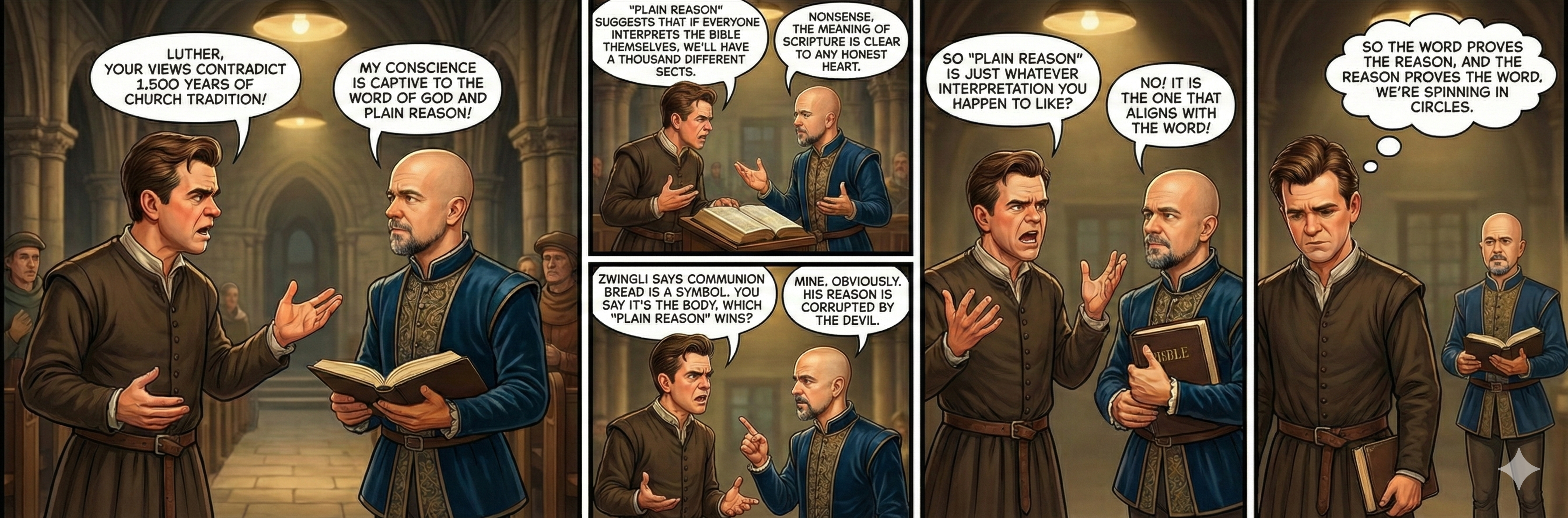

1400 AD to 1600 AD: The Reformation and Scriptural Authority

The Reformation in the 16th century, spearheaded by Martin Luther and John Calvin, radically challenged the Church’s authority, emphasizing sola scriptura (Scripture alone) as the highest source of evidence. Luther, in his famous defense at the Diet of Worms (1521), declared:

“Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason… my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything.”

For Luther, faith was a gift from God but could be grounded in the evidential authority of Scripture. Calvin echoed this view in Institutes of the Christian Religion:

“We should seek no other proof of the foundation of our faith than the Word of God.”

At the same time, the Renaissance humanists emphasized empirical observation and intellectual freedom, paving the way for rigorous evidence-based belief to slowly emerge in response to scientific developments.

1600 AD to 1800 AD: The Enlightenment and Rational Faith

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the Enlightenment posed a significant challenge to religious authority. Thinkers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant sought to reconcile faith with reason. In The Reasonableness of Christianity, Locke argued that Christian beliefs were rationally defensible:

“There is no reason to deny what reason shows, even if reason itself cannot demonstrate all the truths of faith.”

Meanwhile, Immanuel Kant in Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason posited that faith must align with moral rationality:

“Faith… must always stand in relation to the practical reason.”

These developments diminished Fideism, which was increasingly seen as incompatible with scientific inquiry. However, partial evidence-based faith remained strong in Christian apologetics, supported by figures such as William Paley with his teleological argument for God’s existence.

2000 AD to Present: Balancing Faith and Evidence

In the modern era, partial evidence-based belief dominates mainstream Christian thought. Apologists like William Lane Craig continue to defend Christianity through both philosophical and historical arguments. Craig asserts:

“It is the witness of the Holy Spirit that gives us the ultimate assurance of Christianity’s truth… but the historical evidence supports this belief.”

Simultaneously, scientific advancements in fields like archaeology and textual criticism have bolstered rigorous evidence-based faith. However, religious experience and personal conviction continue to shape much of Christian spirituality.

The trend reflected in the chart suggests that by 2025 AD, Fideism will have largely diminished, with faith increasingly seen as harmonizing with reason and evidence.

Conclusion

The history of redemptive faith within Christianity reveals a complex interplay between tradition, reason, and evidence. From the dominance of Fideism in the early Church to the current balance between faith and rational inquiry, Christian thought has evolved in response to both internal theological developments and external intellectual movements. As society continues to prioritize empirical knowledge, faith traditions that engage with reason are likely to endure and thrive in the years ahead.

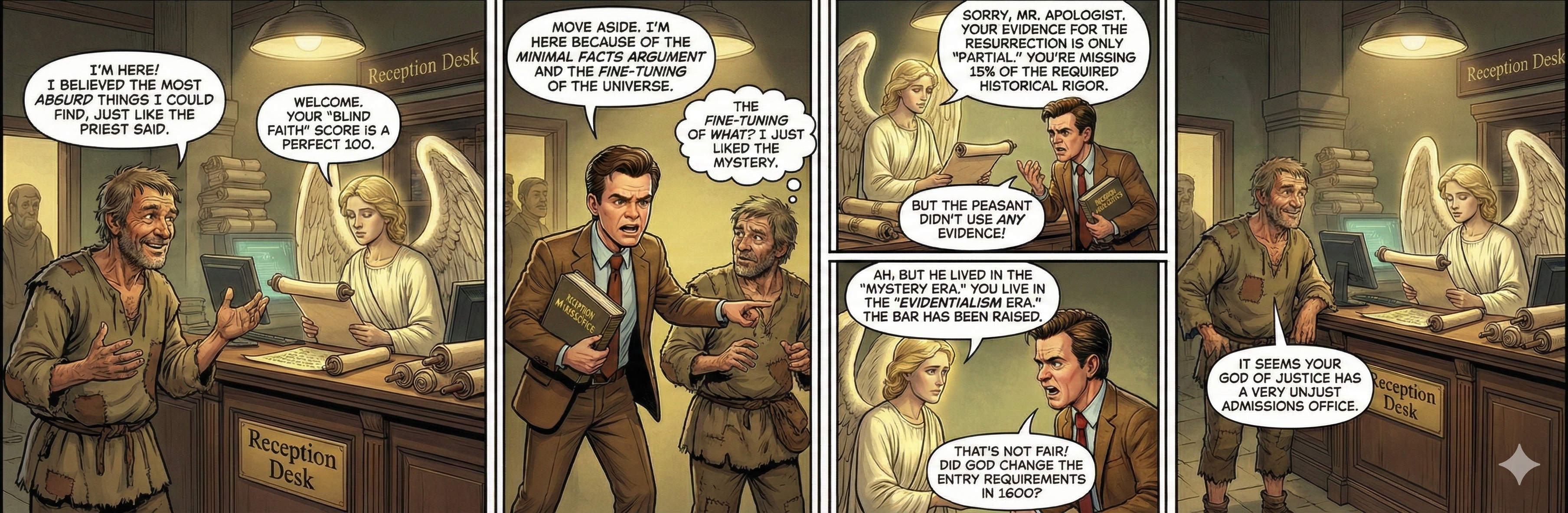

The Coherence Problem in the Historical Evolution of Redemptive Belief

The evolution of redemptive belief within Christianity raises significant philosophical questions about the coherence of such a notion. If God is both just and clear in His revelation, one would expect the criteria for redemption to be consistent and static across time and cultures. However, the historical trajectory of Christian theology reveals dramatic shifts in the required relationship between faith and evidence. In early Christianity, Fideism—emphasizing faith without the need for evidence—was widely promoted. Over time, this gave way to partial evidence-based belief, and in modern eras, some theological frameworks even advocate rigorous evidence-based belief. These variations suggest a fundamental inconsistency in how redemptive belief is defined and understood.

If God is just, His requirements for salvation should be universally accessible and applicable, without favoring those in certain historical or intellectual contexts. Yet, individuals in different eras have faced differing expectations regarding the epistemic grounds of faith. Early Christians were often taught to embrace mysteries beyond reason, while modern believers are encouraged to harmonize faith with scientific inquiry and philosophical rigor. Such shifts imply either that God’s expectations have changed over time or that human understanding of divine requirements is flawed and unreliable. This lack of stability raises doubts about the coherence of the notion of redemptive faith. If God’s revelation were truly clear, such changes should not have occurred. Thus, the dynamic nature of redemptive belief undermines the premise that a just and clear God would have established a singular, enduring standard for salvation.

Syllogistic Formulation of the Argument

Premises:

- If God is just and clear, then the criteria for redemptive belief should remain consistent and universally accessible across time.

- The criteria for redemptive belief have changed significantly over time (e.g., from Fideism to evidence-based belief).

- Inconsistent and changing criteria imply either divine ambiguity or a flawed human understanding of God’s requirements.

- A just and clear God would not permit essential criteria for salvation to be ambiguous or inconsistent.

Conclusion:

— Therefore, the changing dimensions of redemptive belief over time reflect an incoherent notion of redemptive belief if God is both just and clear.

Symbolic Logic Formulation

Let:

: “God is just”

: “God is clear in His revelation”

: “Criteria for redemptive belief are consistent across time”

: “Criteria for redemptive belief change over time”

: “not”

: “implies”

(If God is just and clear, the criteria for redemptive belief should be consistent.)

(The criteria for redemptive belief have changed over time.)

(Consistency implies that the criteria do not change.)

(Since the criteria have changed, they are not consistent.)

(By modus tollens, if God is just and clear, the criteria should not have changed.)

(Therefore, either God is not just, not clear, or the notion of redemptive belief is incoherent.)

This argument demonstrates that, if God’s justice and clarity are taken as axioms, the historical shifts in redemptive faith suggest that human conceptions of salvation may be fundamentally incoherent. Either the notion of redemptive faith needs reconceptualization, or theological assumptions about divine justice and clarity require reassessment.

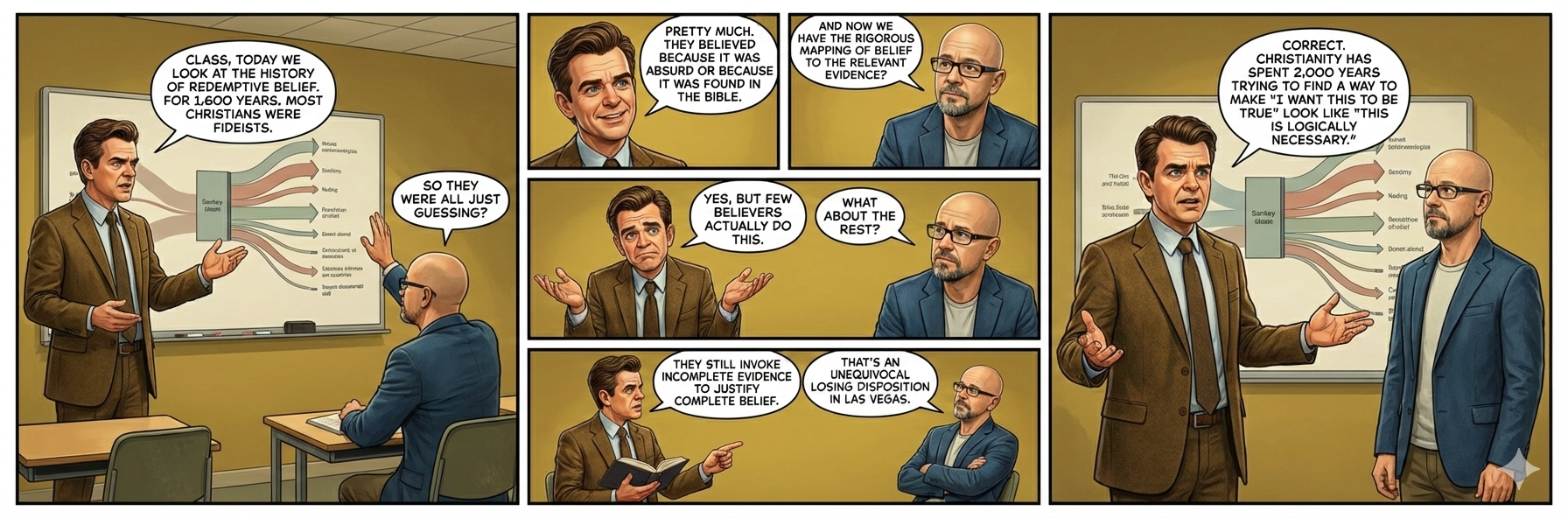

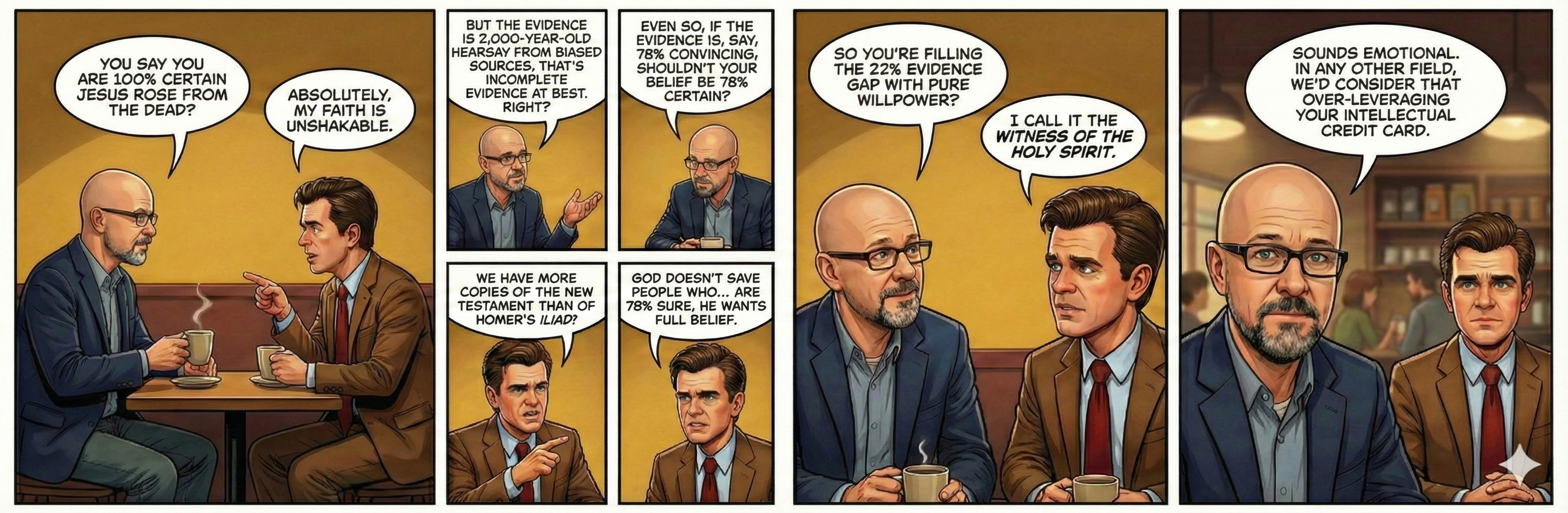

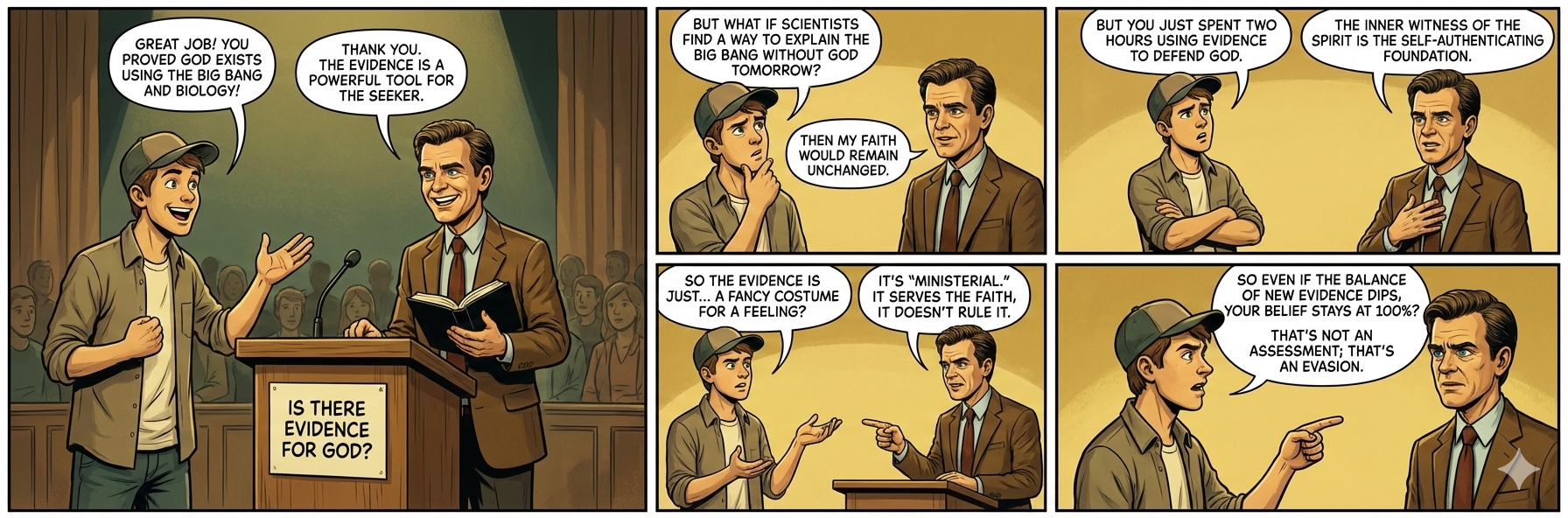

Rational Belief and the Distance from Christian Redemptive Faith

Rational belief is defined as a degree of belief that aligns proportionally with the degree of relevant evidence. In other words, rationality requires that one should believe in a proposition only to the extent that evidence supports it. The philosopher David Hume famously summarized this principle in his Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding:

“A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.”

Christian redemptive faith, however, often departs from this ideal. Historically, Christianity has shifted between Fideism and partial evidence-based belief, with each movement away from evidence-proportioned belief creating philosophical tensions. Early Christian leaders, such as Tertullian, emphasized the virtue of belief without evidence, famously stating, “I believe because it is absurd.” Faith in this period was seen as transcending human reason entirely. Even with the rise of Scholasticism, which sought to integrate faith and reason, there remained a strong emphasis on accepting mysteries that exceeded human comprehension.

In modern Christian apologetics, partial evidence is often presented to support core doctrines, but this evidence frequently falls short of the standards required by rational belief. For example, appeals to historical evidence (such as the resurrection of Christ) often rely on scriptural narratives that are themselves contested by historians. Additionally, philosophical arguments for God’s existence (e.g., the cosmological and teleological arguments) provide only indirect support for Christian doctrines and are insufficient to justify a high degree of belief proportional to evidence. Apologist William Lane Craig, for instance, acknowledges that faith ultimately rests on the “witness of the Holy Spirit,” which is subjective and unverifiable, rather than being purely evidence-based.

This gap between Christian faith and rational belief raises the question of whether Christianity is asking for more belief than its evidence warrants. While modern theologians attempt to balance reason and revelation, Christian faith remains rooted in doctrines that are only partially defensible by empirical or philosophical evidence. As such, it stands at a significant distance from the ideal of belief proportioned fully to the degree of relevant evidence. This disconnect suggests that Christianity, like many other religious traditions, maintains an incoherent hybrid epistemology that prioritizes personal conviction and spiritual experience over strict evidential alignment.

Rational belief is a degree of belief that maps to the degree of the relevant evidence.

Thanks for another interesting piece (as usual). I might add that even the “flying” fortress theologians have tried to build…