Introduction

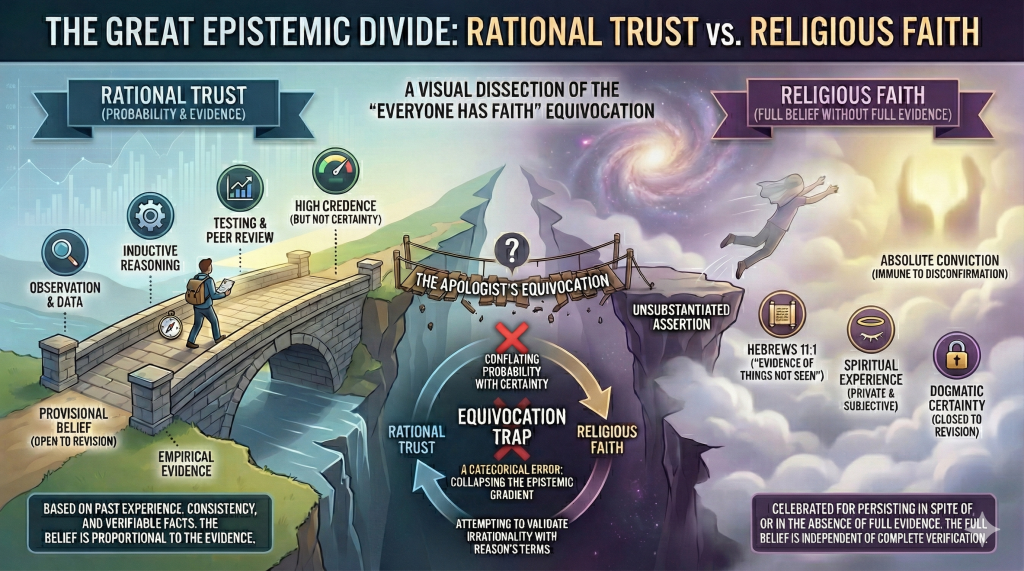

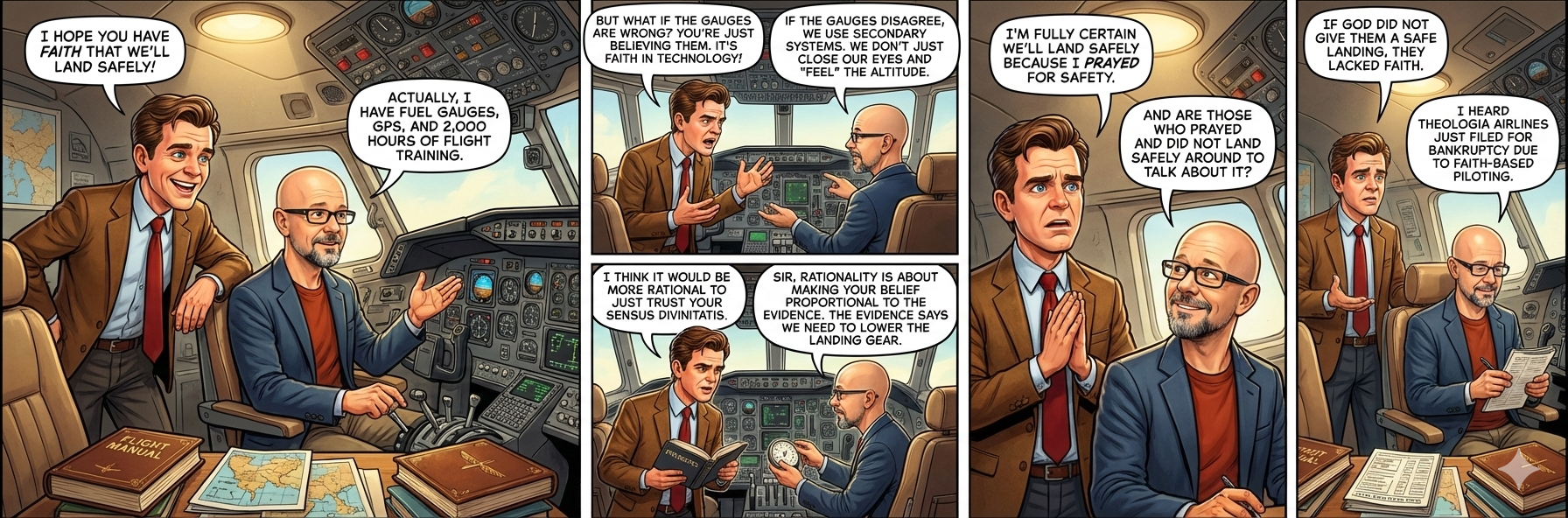

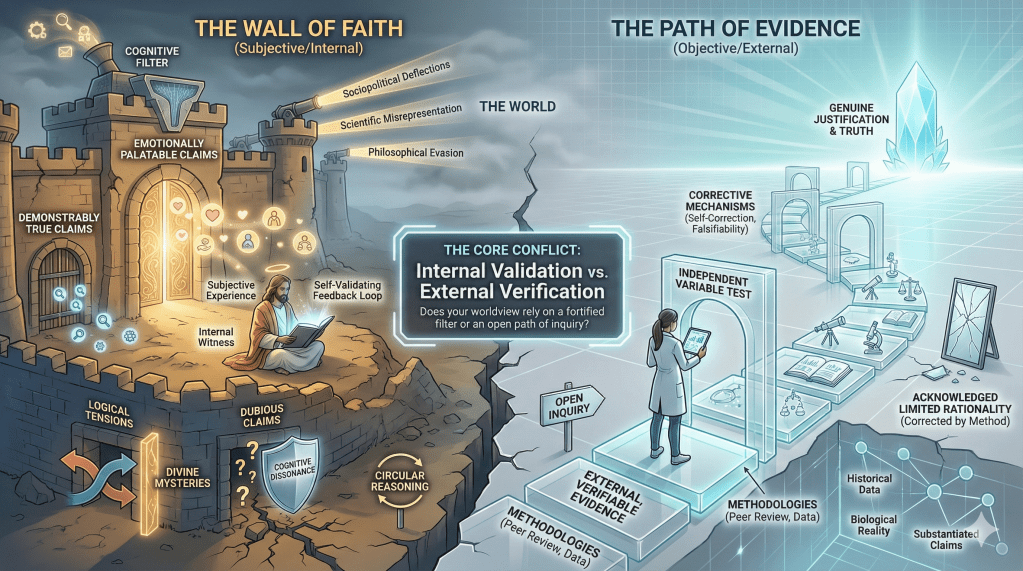

The concept of faith has become a focal point in public discourse, particularly regarding its role in belief formation and rational thought. Traditionally, faith is defined as a belief that exceeds the degree of supporting evidence. When criticized, defenders of faith often argue that it is a universal human trait, asserting either that faith is unavoidable or that people unknowingly harbor faith-based beliefs. These strategies aim to shield faith from critique by conflating it with general belief systems, creating semantic confusion. This essay examines these claims and demonstrates through syllogistic arguments that faith, as traditionally defined, is inherently irrational.

The Ubiquity Defense of Faith

Defenders of faith use two primary arguments to normalize its role:

- The Unavoidability Claim: Faith is inescapable since no one can empirically verify all beliefs.

- The Unawareness Claim: Many hold beliefs exceeding evidence unknowingly, thus unknowingly practicing faith.

These arguments aim to blur distinctions between faith-based beliefs and those grounded in evidence, normalizing faith and deflecting criticism.

Semantic Confusion and Its Effects

This conflation has two major effects:

- Normalization: By broadening the definition of faith, it becomes indistinguishable from ordinary cognition, shielding it from critique.

- Insulation: Equating faith with rational belief deflects specific criticisms of faith by equating them with criticisms of general reasoning.

These effects obscure the key distinction: faith-based beliefs exceed evidence, whereas rational beliefs align with it.

Syllogistic Defense of Faith’s Irrationality

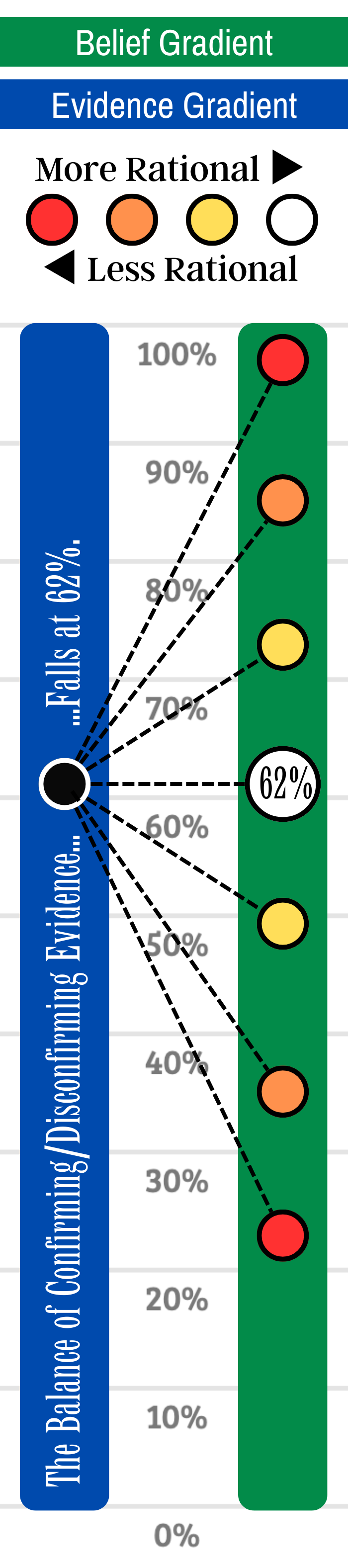

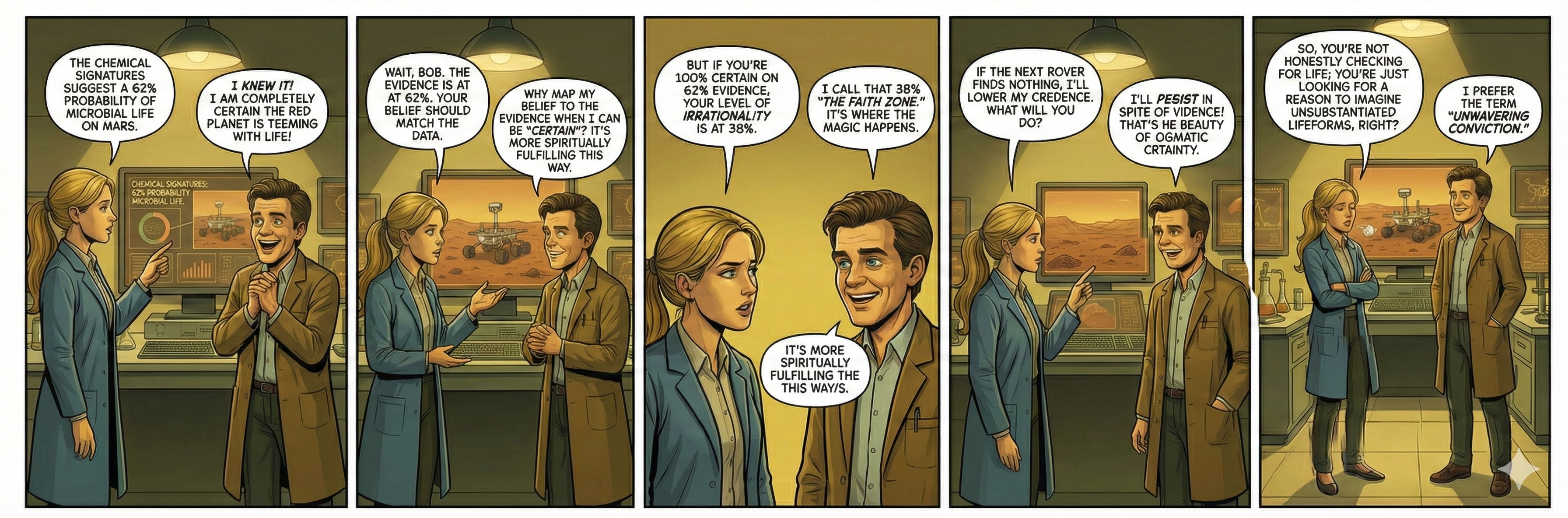

Syllogism 1: The Principle of Proportionality

Premises:

- Rationality requires belief to be proportional to evidence.

- Faith involves belief that exceeds evidence.

- Conclusion: Faith violates proportionality and is irrational.

- Explanation: Rational thought demands evidence-proportioned belief. Faith, by definition, disregards this principle, making it incompatible with rationality.

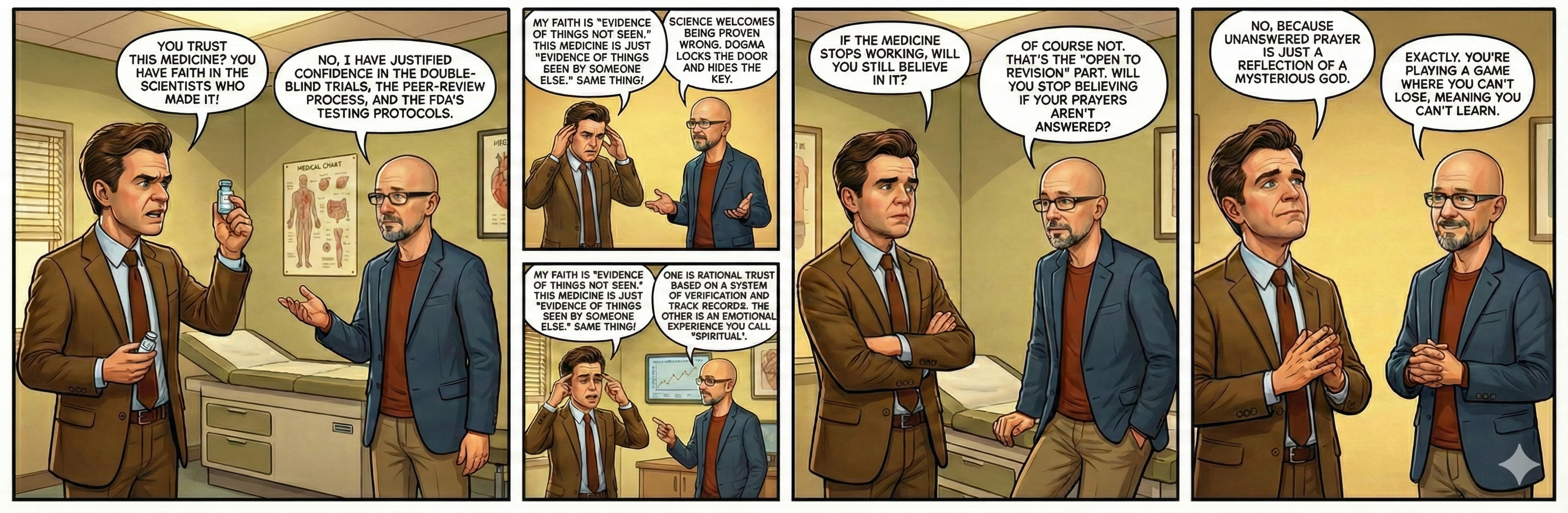

Syllogism 2: The Requirement of Sufficient Evidence

Premises:

- Believing without sufficient evidence is irrational.

- Faith involves belief without sufficient evidence.

- Conclusion: Faith is irrational.

- Explanation: Rational beliefs rest on adequate evidence. Faith, lacking justification, violates this standard.

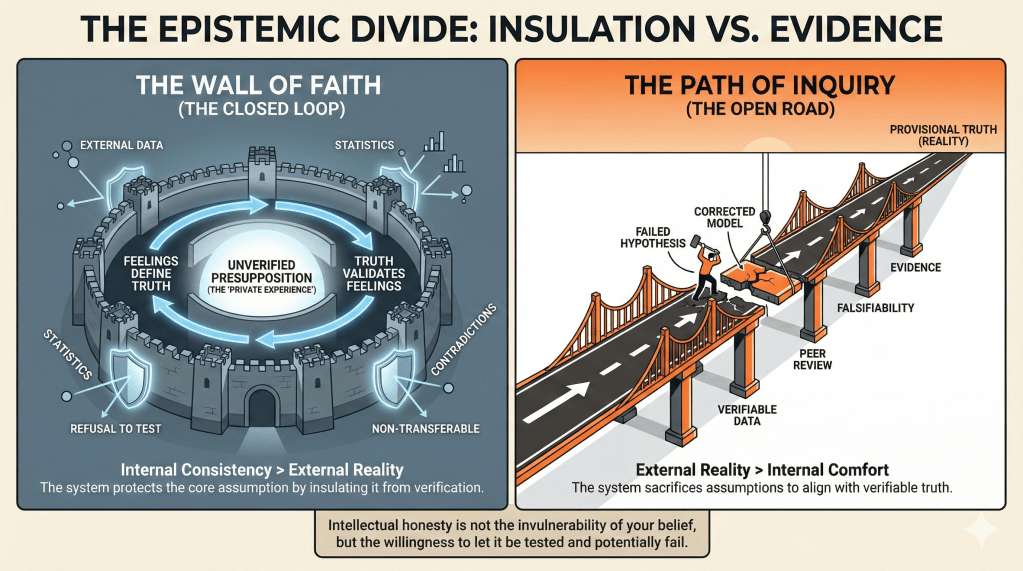

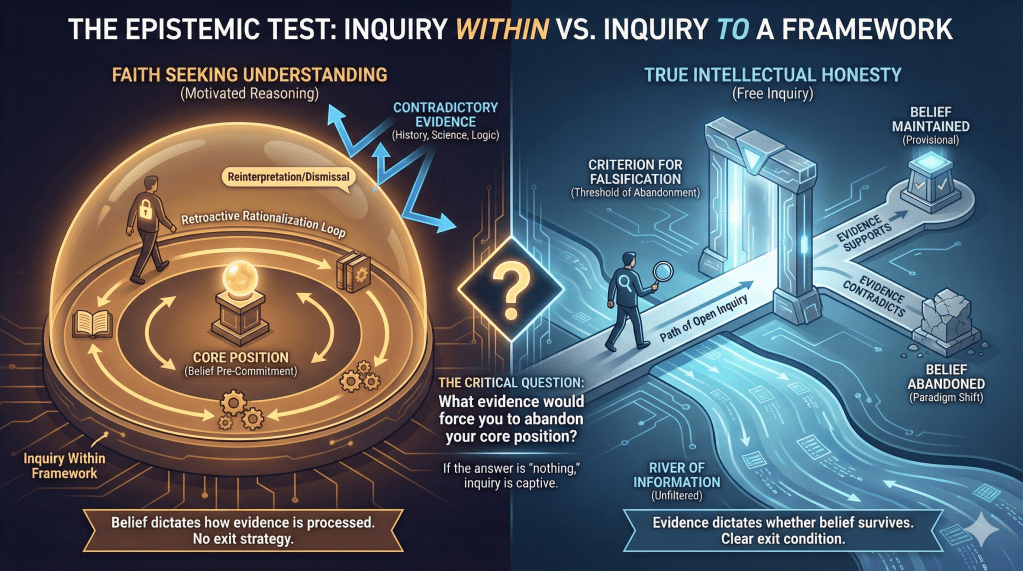

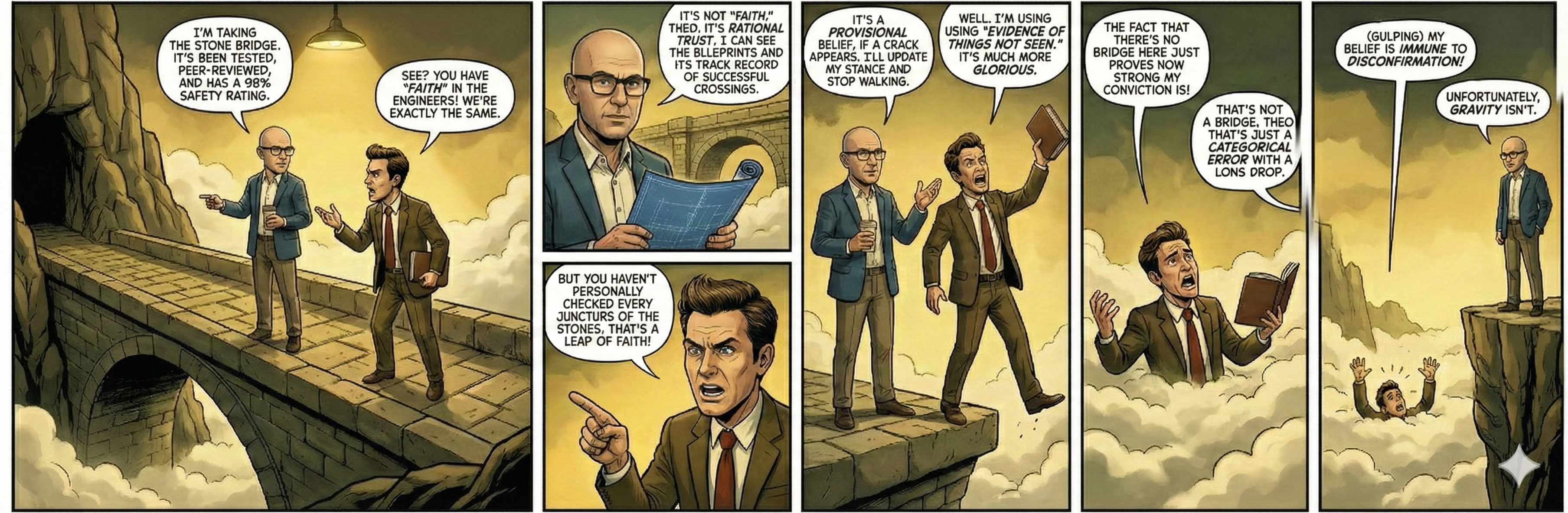

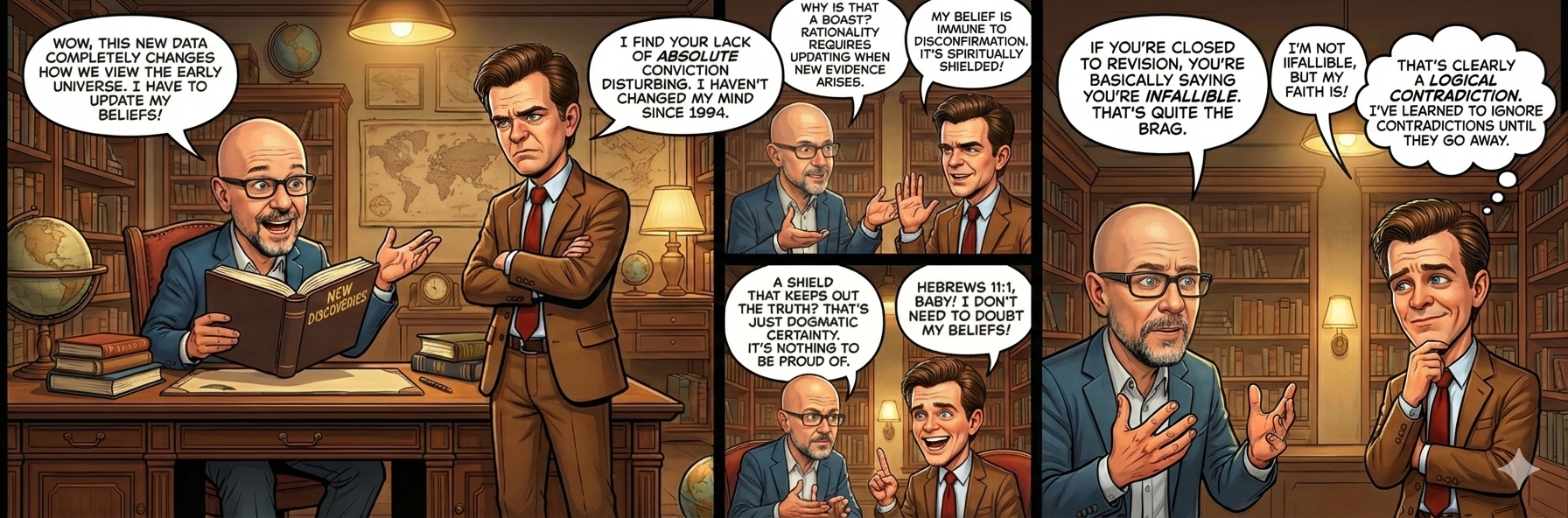

Syllogism 3: Resistance to Evidence Revision

Premises:

- Rationality requires updating beliefs when credible new evidence arises.

- Faith resists belief revision despite new evidence.

- Conclusion: Faith is irrational.

- Explanation: Rational agents adapt to evidence, but faith’s rigidity undermines this principle.

Syllogism 4: Logical Inconsistency

Premises:

- Rational beliefs must avoid logical contradictions.

- Faith permits beliefs that are inconsistent or contradictory.

- Conclusion: Faith is irrational.

- Explanation: Logical consistency is central to rational systems, but faith often tolerates contradictions.

Syllogism 5: The Problem of Arbitrary Belief

Premises:

- Rationality rejects arbitrary beliefs.

- Faith relies on subjective or arbitrary justifications.

- Conclusion: Faith is irrational.

- Explanation: Arbitrary belief formation undermines rational standards, which faith inherently lacks.

Addressing Defenses of Faith

The Unavoidability Claim

While human cognition often works with incomplete evidence, rational beliefs differ fundamentally from faith in that they:

- Remain Open to Revision: Rational beliefs evolve with new evidence. Faith does not.

- Rest on Evidence: Even provisional beliefs derive from the best available data. Faith disregards such proportionality.

- Serve Pragmatic Needs: Assumptions for functionality (e.g., inductive reasoning) are based on empirical patterns, unlike faith.

The Unawareness Claim

Even if individuals hold beliefs disproportionate to evidence unknowingly, this does not equate to faith:

- Implicit Rationality: Many beliefs adjust unconsciously to evidence, aligning with rational principles.

- Awareness of Excess: Faith requires conscious belief exceeding the relevant evidence, evidence which is absent in such cases.

Misattributions of Faith

Common examples defenders cite include:

- Scientific Trust: Founded on empirical evidence and continuous revision.

- Induction: Rationally justified by statistical probabilities and past observations.

- Pragmatic Assumptions: Based on repeatable, observable patterns.

These involve proportionate belief and openness to revision, distinguishing them from faith.

Conclusion

Faith, as traditionally defined, contradicts the core principles of rationality: proportionality, evidence-based justification, openness to revision, logical consistency, and non-arbitrariness. Efforts to normalize faith through semantic confusion fail to withstand scrutiny. Recognizing faith’s intrinsic irrationality is critical for fostering a culture of evidence-based reasoning and meaningful discourse.

Scenario: Alice & Bob

Let:

: a proposition (e.g., “There is life on Mars“)

: the degree of relevant evidence supporting

, on a scale from 0 to 1

: the degree of belief or credence individual

assigns to

: “Individual

is rational in believing

”

: approximate equality (within a rational tolerance threshold)

The general principle of rational belief proportionality can be stated formally:

That is, individual x is rational in believing proposition b if and only if their credence in is approximately equal to the degree of evidence for

.

Case: Alice and Bob

- Alice’s credence:

- Bob’s credence:

- Shared evidence:

Apply the rationality condition to each:

- Alice:

✓Rational — Alice’s belief matches the available evidence. - Bob:

❌ Irrational — Bob’s belief exceeds the support provided by the evidence.

Interpretation

This model reflects a Bayesian epistemology in which rational belief is not binary (believe or disbelieve), but graded and responsive to the strength of the evidence. Alice’s belief is rational because her credence that there is life on Mars reflects the degree of evidential support. Bob, by contrast, demonstrates overconfidence—his full belief (certainty) is not warranted by the 85% evidential backing. Thus, Bob is irrational not because his belief is false, but because the strength of his belief that there is life on Mars exceeds the strength of his evidence.

Additional Symbolic Logic Representations of the Syllogisms

Additional Symbolic Logic Support

Definitions for the Symbolic Logic

: The universal quantifier, meaning “for all.” Example:

means “for all x.”

: The existential quantifier, meaning “there exists.” Example:

means “there exists an x.”

: The material conditional, meaning “if … then …” Example:

means “if P, then Q.”

: The logical conjunction, meaning “and.” Example:

means “P and Q.”

: The logical disjunction, meaning “or.” Example:

means “P or Q.”

: The logical negation, meaning “not.” Example:

means “not P.”

: The biconditional, meaning “if and only if.” Example:

means “P if and only if Q.”

: “Degree of belief x has in proposition p.” This represents the confidence level an individual assigns to a proposition.

: “Degree of evidence supporting proposition p.” This represents the amount of evidence available for a proposition.

: “x is rational.” This denotes whether a person or agent acts in accordance with principles of rationality.

: “x has faith in proposition p.” Faith here implies belief in excess of the evidence.

: “x’s belief system is logically consistent.” This refers to the internal coherence of a set of beliefs held by an individual.

: “x’s belief system is logically inconsistent.” This indicates contradictions within a set of beliefs.

: “x adjusts belief in proposition p in response to new evidence.” This denotes openness to revising beliefs.

: “New credible evidence contradicts x’s belief in proposition p.” This refers to evidence that directly challenges an existing belief.

: “x makes the claim that proposition p is true.” This indicates an assertion that requires justification.

: “x has the burden of proof for proposition p.” This refers to the responsibility of justifying a claim.

: “x believes that proposition p is true.” This denotes belief in a specific proposition.

: “x does not believe that proposition p is true.” This represents disbelief or lack of belief.

: “x’s belief in proposition p is based on objective criteria.” This refers to beliefs grounded in logical, evidence-based reasoning.

: “x’s belief in proposition p is arbitrary.” This denotes belief formed without objective justification.

: “False equivalence.” This occurs when two distinct concepts are unjustifiably equated.

: “The distinction between rational and irrational beliefs is meaningful.” This asserts the necessity of differentiating rationality levels.

: “Incoherence occurs.” This indicates logical or conceptual inconsistency.

: “God exists.” This is the proposition commonly discussed in the context of theism and atheism.

: “Theism.” This denotes belief in the existence of deities.

: “Atheism.” This refers to the lack of belief in the existence of deities.

Syllogism 1: The Principle of Proportionality

Explanation: This syllogism demonstrates that rationality requires belief to align proportionally with evidence. Faith, by exceeding this proportionality, violates rationality.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- For all individuals (denoted by

) and for all propositions (

):

- If someone is rational (

), then their degree of belief in a proposition (

) must equal the degree of evidence supporting that proposition (

).

- If someone has faith in a proposition (

), their belief in that proposition exceeds the evidence supporting it (

).

- Therefore, having faith (

) implies that the person is not rational (

).

- If someone is rational (

Syllogism 2: The Requirement of Sufficient Evidence

Explanation: Rationality demands sufficient evidence for belief. Faith, characterized by insufficient or contrary evidence, fails this requirement.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- For all individuals (

) and propositions (

):

- If someone believes a proposition (

) but the evidence for that proposition is insufficient (

), then they are not rational (

).

- Faith in a proposition (

) implies believing in it without sufficient evidence (

).

- Therefore, having faith (

) implies the person is not rational (

).

- If someone believes a proposition (

Syllogism 3: Resistance to Evidence Revision

Explanation: Rational agents revise their beliefs when credible evidence contradicts them. Faith resists such revisions, making it irrational.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- For all individuals (

) and propositions (

):

- If someone is rational (

) and new credible evidence (

) contradicts their belief, they must adjust their belief (

).

- If someone has faith (

) and new credible evidence (

) contradicts their belief, they refuse to adjust it (

).

- Therefore, having faith (

) implies the person is not rational (

).

- If someone is rational (

Syllogism 4: Logical Consistency and Non-Contradiction

Explanation: Rationality requires logical consistency in belief systems. Faith, which allows contradictions, undermines this principle.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- For all individuals (

):

- If someone is rational (

), their belief system must be logically consistent (

).

- If someone has faith (

), their belief system is logically inconsistent (

).

- Logical inconsistency (

) implies a lack of logical consistency (

).

- Therefore, having faith (

) implies the person is not rational (

).

- If someone is rational (

Syllogism 5: The Problem of Arbitrary Belief

Explanation: Rationality depends on beliefs being based on objective criteria. Faith, relying on subjective or arbitrary grounds, fails this standard.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- For all individuals (

) and propositions (

):

- If someone is rational (

), their beliefs must be based on objective criteria (

).

- If someone has faith (

), their beliefs are arbitrary (

).

- Arbitrary beliefs (

) imply a lack of objective criteria (

).

- Therefore, having faith (

) implies the person is not rational (

).

- If someone is rational (

Syllogism B1: The Fallacy of Equivocation

Explanation: Effective communication requires consistent term definitions. Redefining “faith” to encompass all beliefs introduces equivocation, undermining clarity.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- If effective communication occurs (

), the term “faith” (

) must be used consistently (

).

- Redefining “faith” (

) makes its use inconsistent (

).

- Therefore, redefining “faith” (

) undermines effective communication (

).

Syllogism B2: The False Equivalence

Explanation: Equating evidence-based and faith-based beliefs constitutes a false equivalence, as these are fundamentally distinct in justification.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- If two beliefs (

and

) are fundamentally different (

) but are unjustifiably equated (

), this constitutes a false equivalence (

).

Syllogism B3: The Incoherence of Universal Faith

Explanation: If all beliefs are considered faith, distinctions between rational and irrational beliefs dissolve, resulting in incoherence.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- If all beliefs are faith (

), distinctions between rational and irrational beliefs are meaningless (

).

- Meaningful distinctions (

) are necessary to avoid incoherence (

).

- Therefore, asserting that all beliefs are faith (

) leads to incoherence (

).

Syllogism C1: Mischaracterizing Atheism as a Faith-Based Belief

Explanation: Atheism is not based on faith because it involves a lack of belief in deities due to insufficient evidence, contrasting with faith’s definition.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- Faith in a proposition (

) occurs if and only if (

) someone believes the proposition (

) and there is insufficient evidence for it (

).

- Atheism (

) means not believing in the proposition that God exists (

).

- There is insufficient evidence for God’s existence (

).

- Therefore, atheism (

) does not involve faith in the proposition that God exists (

).

Syllogism C2: The Burden of Proof

Explanation: The burden of proof lies with those making positive claims. Theism requires faith because it asserts God’s existence without sufficient evidence, whereas atheism does not.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- If someone makes a claim (

), they carry the burden of proof (

).

- Theism (

) makes the claim that God exists (

).

- Atheism (

) does not make this claim (

).

- Believing a proposition (

) without sufficient evidence (

) constitutes faith (

).

- There is insufficient evidence for God’s existence (

).

- Theists believe in God (

), so theism requires faith (

).

- Atheists do not believe in God (

), so atheism does not require faith (

).

Syllogism C3: Confusion Between Disbelief and Belief

Explanation: Disbelief arises from insufficient evidence and does not constitute faith. This syllogism clarifies the distinction.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- Faith in a proposition (

) occurs if and only if (

) someone believes the proposition (

) and there is insufficient evidence (

).

- Disbelief in a proposition (

) occurs if and only if (

) someone does not believe it (

) and there is insufficient evidence (

).

- Therefore, if someone disbelieves a proposition (

), they do not have faith in it (

).

Syllogism C4: The Inversion of Faith Requirements

Explanation: Faith is required to believe without sufficient evidence. Theism requires faith, while atheism, grounded in disbelief due to insufficient evidence, does not.

Natural Language Walkthrough:

- Believing a proposition (

) without sufficient evidence (

) requires faith (

).

- Theism (

) involves belief in God (

) without sufficient evidence (

).

- Atheism (

) involves not believing in God (

) due to insufficient evidence (

).

- Therefore, theism (

) requires faith in God (

), while atheism (

) does not (

).

See also:

Leave a comment