Symbolic Logic Analysis of Pascal’s Wager and Contradictory Hell Claims

To analyze why Pascal’s Wager carries no weight in light of contradictory, evidence-free claims of Hell, we use the following symbolic logic.

Definitions

- P: The Christian God exists.

- ¬P: The Christian God does not exist.

- Q: The Muslim God exists.

- ¬Q: The Muslim God does not exist.

- C: Consequences of belief/disbelief (Heaven or Hell based on a specific God).

Core Structure of Pascal’s Wager

- If P is true and you believe, you go to Christian Heaven.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If P is true and you don’t believe, you go to Christian Hell.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If ¬P is true, your belief in the Christian God is inconsequential.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

Pascal’s Wager assumes these propositions should rationally lead you to believe in P, as the potential consequences of disbelief (eternity in Hell) outweigh the consequences of belief (at worst, no significant cost).

Contradictory Hell Claims

Consider the Muslim version of Pascal’s Wager:

- If Q is true and you believe, you go to Muslim Heaven.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If Q is true and you don’t believe, you go to Muslim Hell.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If ¬Q is true, your belief in the Muslim God is inconsequential.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

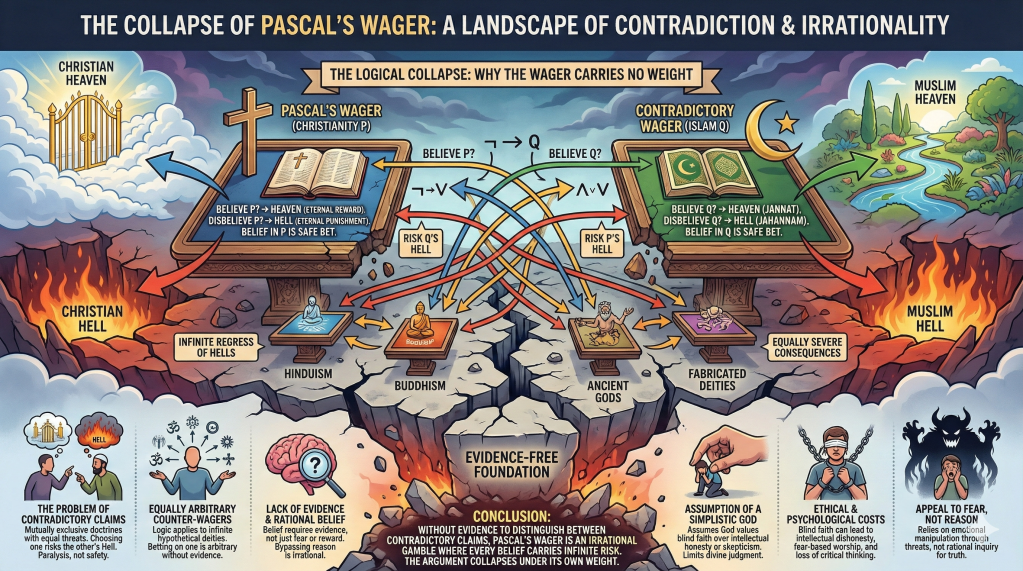

Logical Conflict

Both P and Q present mutually exclusive claims about the nature of God, Heaven, and Hell. The arguments for P and Q have no supporting evidence, yet both assert equally severe consequences for disbelief.

- If you believe in P, you avoid Christian Hell but risk Muslim Hell.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If you believe in Q, you avoid Muslim Hell but risk Christian Hell.

- Symbolically:

.

- Symbolically:

- If you reject both P and Q because they are evidence-free, you face both Christian Hell (

) and Muslim Hell (

)—an absurd conclusion that undermines the argument’s rational force.

Generalization to Contradictory Claims

- For any religious claim

that posits an evidence-free Hell for disbelief, there exists an infinite set of contradictory claims

, each asserting equally severe consequences.

- Without evidence to privilege any one claim, belief in one arbitrary claim

carries the same risk of Hell from all other contradictory claims.

- Symbolically:

Since are all evidence-free, no rational basis exists for privileging any single

.

Conclusion

Believing in P (Christian God) to avoid Hell is irrational because:

- The same reasoning applies to an infinite number of other claims (

), which equally threaten Hell for disbelief.

- Without evidence to distinguish among these claims, privileging one is arbitrary and irrational.

- The “wager” collapses because every belief carries infinite risk due to the existence of contradictory Hell claims.

Thus, Pascal’s Wager carries no weight in the absence of evidence, as it can be applied equally to all mutually exclusive claims.

More comprehensive symbolic logic formulations:

Pascal’s Wager formalized, and why it breaks

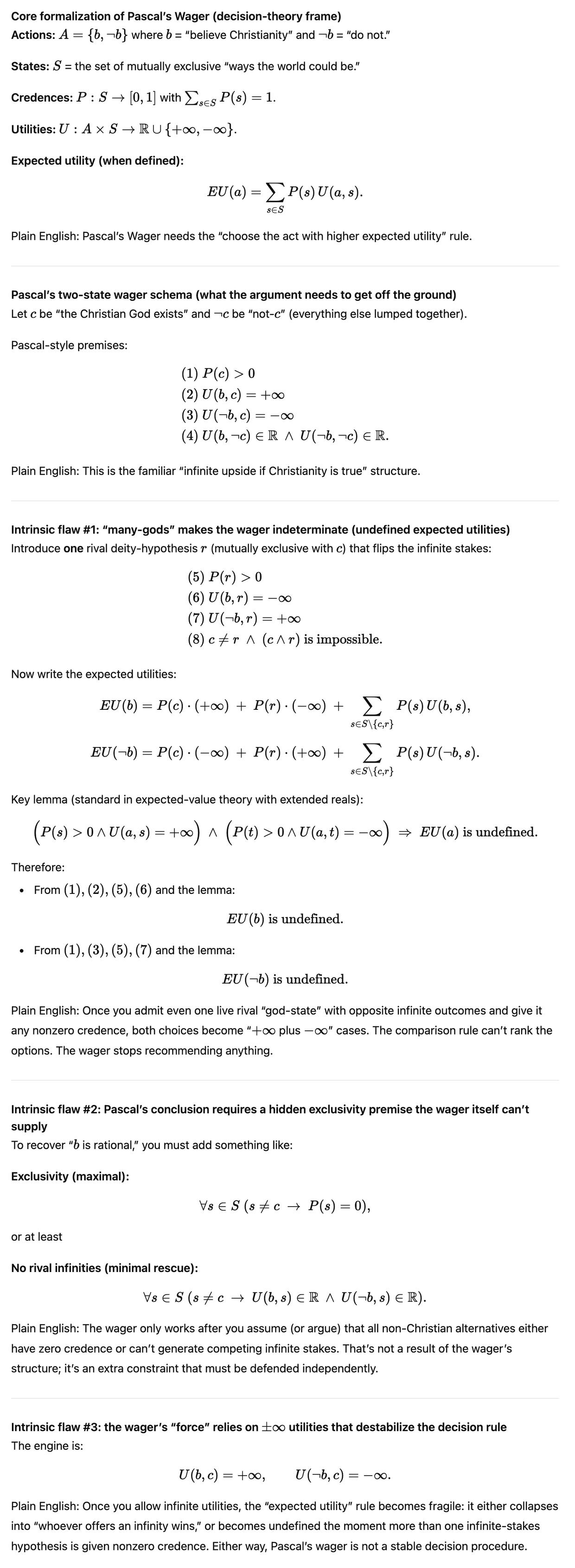

- Core formalization (decision-theory frame)

✓ Actions: where

means “believe Christianity” and

means “do not.”

✓ States: is the set of mutually exclusive “ways the world could be.”

✓ Credences: with

.

✓ Utilities: .

✓ Expected utility (when defined): .

Plain English: the wager needs the rule “choose the action with the higher expected utility.”

- The two-state wager schema (what Pascal’s move needs)

Let be “the Christian God exists” and

be “not-

” (everything else lumped together).

Plain English: infinite upside if is true, and only finite costs otherwise.

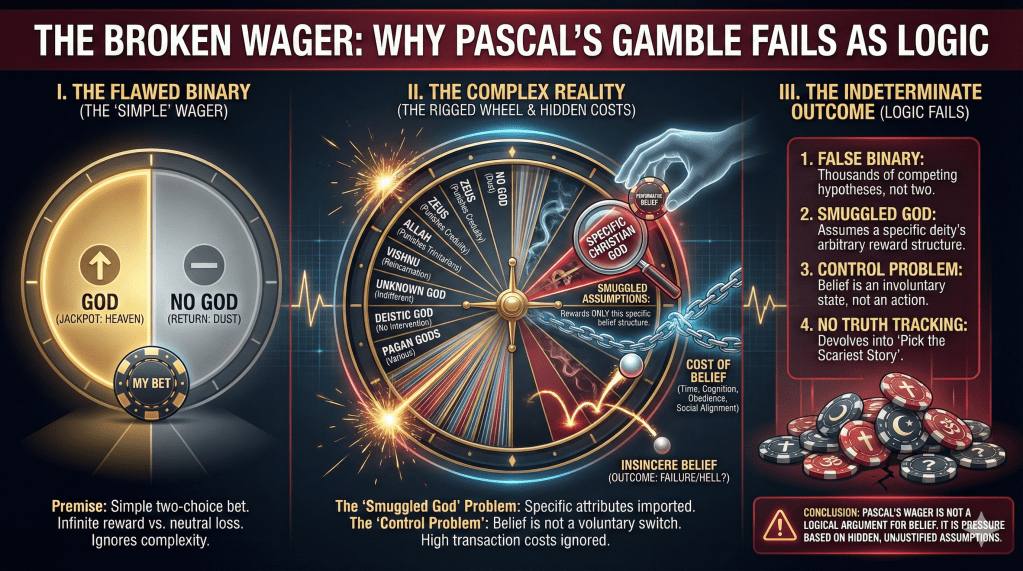

- Intrinsic flaw 1: adding even one rival deity makes the wager indeterminate

Introduce one rival hypothesis (mutually exclusive with

) that flips the infinite stakes:

Now the expected utilities become:

Key lemma (mixed infinities with positive weight break expected value):

Therefore:

Plain English: the moment you allow even one live rival “god-state” with opposite infinite stakes and give it any nonzero credence, the wager cannot rank the options. It stops recommending anything.

- Intrinsic flaw 2: the wager needs a hidden exclusivity premise it cannot justify

To recover “choose ,” you must add something like:

Exclusivity (maximal rescue):

Or at least:

No rival infinities (minimal rescue):

Plain English: the wager only works after you assume (or independently argue) that alternatives to either have zero credence or cannot generate competing infinite payoffs. That is not supplied by the wager’s structure.

- Intrinsic flaw 3: the argument’s force depends on

utilities that destabilize the decision rule

The engine is:

Plain English: once you permit infinite utilities, expected-utility comparison either collapses into “whoever promises an infinity wins,” or becomes undefined as soon as multiple infinite-stakes hypotheses have nonzero credence. Either way, the wager is not a stable decision procedure.

- Compact “theorem” form (useful as a closing punch)

So the wager cannot yield a determinate recommendation without suppressing rivals by assumption.

A variant:

Why Pascal’s Wager Fails as a Rational Argument

Pascal’s Wager is often invoked as a pragmatic justification for belief in God, specifically the Christian God. It argues that, given the potential infinite reward of Heaven and the infinite punishment of Hell, belief in God is the safer “bet.” However, upon closer examination, this wager collapses under its own weight due to several key flaws. These flaws render Pascal’s Wager not only unpersuasive but intellectually impotent as a guide for rational decision-making.

1. The Problem of Contradictory Claims

The first and most significant flaw in Pascal’s Wager is the existence of countless competing religious claims, each asserting mutually exclusive doctrines about God, Heaven, and Hell. For example, Christians warn of eternal punishment for disbelieving in the Christian God, while Muslims assert the same for disbelieving in Allah. Hinduism, Buddhism, and other religions also offer unique consequences tied to their doctrines. Without evidence to favor one religion over another, Pascal’s Wager becomes paralyzed. A person who bets on the Christian God risks facing the Muslim Hell, and vice versa. The wager provides no mechanism to resolve this impasse, leaving the individual with no rational basis for selecting one belief over another.

2. Equally Arbitrary Counter-Wagers

The logic of Pascal’s Wager can be applied to any number of fabricated or hypothetical deities. Imagine a deity who rewards disbelief in all gods with eternal bliss and punishes belief with eternal torment. Such a claim, though entirely unsupported, carries the same logical weight as Pascal’s original wager because it relies on the same appeal to consequences rather than evidence. If we are to accept Pascal’s reasoning, we must also accept the countless counter-wagers that can be devised. This highlights the wager’s arbitrariness and exposes its failure as a method for rational belief formation.

3. The Role of Evidence in Belief Formation

Pascal’s Wager sidesteps the most critical component of rational belief: evidence. Beliefs are not voluntary decisions made based on potential rewards or punishments; they are conclusions drawn from the weight of evidence. To ask someone to believe in a specific deity without evidence is to ask them to bypass reason entirely. Even if we were to accept Pascal’s pragmatic approach, it is unclear how one could force oneself to believe in a claim that lacks evidentiary support. Genuine belief cannot be conjured through fear or reward alone; it requires reasoned conviction.

4. Assumption of a Simplistic God

Pascal’s Wager assumes that belief, and belief alone, is sufficient to secure a reward in the afterlife. However, this conception of God is overly simplistic and anthropocentric. What if God values intellectual honesty, skepticism, or evidence-based reasoning over blind faith? What if God rewards those who disbelieve in unsupported claims rather than those who believe out of fear or convenience? By assuming that God operates according to Pascal’s limited framework, the wager unjustifiably narrows the possibilities of divine judgment.

5. The Ethical and Psychological Costs of Belief

The wager also ignores the potential costs of belief, both ethical and psychological. Committing to a religion often requires adherence to specific doctrines, some of which may conflict with one’s sense of personal well-being, social harmony, or intellectual integrity. Blindly choosing belief in God to “hedge one’s bets” can lead to intellectual dishonesty, a life of fear-based worship, and the abdication of critical thinking. These costs are not insignificant and must be weighed against the supposed benefits of belief.

6. The Infinite Regress of Hells

Pascal’s Wager relies on the fear of eternal punishment, but this logic can be extended to an infinite regress of Hells. Each religious or fabricated claim of Hell poses a threat to nonbelievers, resulting in a scenario where no belief is safe. The individual is trapped in a web of conflicting eternal consequences, unable to resolve which path avoids the greatest harm. This renders the wager meaningless, as the same reasoning can justify belief in an infinite number of contradictory deities.

7. The Wager’s Appeal to Fear

Finally, Pascal’s Wager operates on an appeal to fear rather than reason. It does not offer evidence or rational justification for belief but instead attempts to coerce belief through the threat of eternal suffering. This approach is inherently flawed, as it prioritizes emotional manipulation over intellectual inquiry. A rational person seeks truth based on evidence, not threats or promises of rewards.

Conclusion

Pascal’s Wager fails as a rational argument for belief in God. Its reliance on unsubstantiated claims, its inability to address contradictory religious doctrines, and its disregard for evidence render it intellectually impotent. Moreover, its reliance on fear, arbitrariness, and oversimplified assumptions about God and belief further undermine its credibility. Rational belief cannot be built on such a precarious foundation. Instead, belief should be proportionate to evidence, not the consequences imagined by unsupported claims.

A Dialogue Between Two Theists: A Christian and a Muslim

Christian: Ahmed, you know that rejecting Jesus Christ as your savior will condemn you to eternal damnation, right? The Bible is clear: “No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). If you don’t accept Jesus, you’re risking Hell for eternity.

Muslim: James, I respect your beliefs, but you’re mistaken. Allah has revealed through the Quran that salvation only comes through submission to Him. “Indeed, the religion in the sight of Allah is Islam” (Quran 3:19). If you don’t accept the Shahada—testifying that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is His messenger—you’ll spend eternity in Jahannam, our Hell.

Christian: But the Quran was written centuries after the Bible, Ahmed. It contradicts God’s word. Jesus is the only path to salvation, not Muhammad. If you reject Him, you’ll burn forever in the lake of fire.

Muslim: And I could say the same about the Bible, James. It’s been altered and corrupted over time. The Quran is Allah’s final and unaltered revelation. If you die in disbelief of Allah, your punishment will be eternal torment.

Christian: But Ahmed, what if you’re wrong? You’re taking a huge gamble with your soul by rejecting Jesus. Think about the consequences—eternal suffering! Why risk it?

Muslim: And what if you’re wrong, James? If you die as a disbeliever in Allah, you will face Jahannam. The fire is eternal, and the pain unimaginable. Can you really afford to reject Islam and risk such a fate?

Christian: Ahmed, this is absurd. If we both follow your logic, I’d have to accept Islam to avoid Muslim Hell, and you’d have to accept Christianity to avoid Christian Hell. But that’s impossible—we can’t both fully commit to two contradictory religions.

Muslim: Exactly, James. The same logic applies in reverse. If I believed in Christianity just to avoid Hell, I’d still face the wrath of Allah for disbelieving in Islam. Both of us can’t be right, but both of us can be wrong.

Christian: But then, how do we decide which of us is correct? We both claim eternal punishment for disbelief, but we have no way of proving that our specific Hell even exists.

Muslim: That’s the problem, isn’t it? We’re both relying on fear of unsubstantiated threats to argue for belief. Without evidence, we’re just making baseless claims and demanding the other submit to them.

Christian: So, if we can’t provide evidence for either Hell, what’s the point of making these threats in the first place? They cancel each other out.

Muslim: Exactly. It’s like telling someone to fear every deity ever imagined. There’s no end to the claims, and no rational way to decide which one to believe in. It’s absurd.

Christian: So what do we do, Ahmed? Just give up trying to scare people into belief?

Muslim: Maybe. If our claims about Hell can’t be supported by evidence, then they’re just empty threats. Maybe it’s time we focus on evidence instead of fear-mongering. Otherwise, we’re just chasing each other in circles.

Christian: I hate to admit it, but you’re right. This is exhausting—and irrational.

Conclusion

This dialogue illustrates the absurdity of mutually exclusive Hell claims. When two theists try to impose Pascal’s Wager logic on one another, they find themselves trapped in an endless loop of unsubstantiated threats. Without evidence to favor one belief over the other, both claims cancel each other out, highlighting the intellectual impotence of such arguments.

The Free of Faith Spotify episode on Pascal’s Wager

Thanks for another interesting piece (as usual). I might add that even the “flying” fortress theologians have tried to build…