The Reasons I Walked away from Faith

Introduction: A Life Rooted in Faith, Questioned by Reason

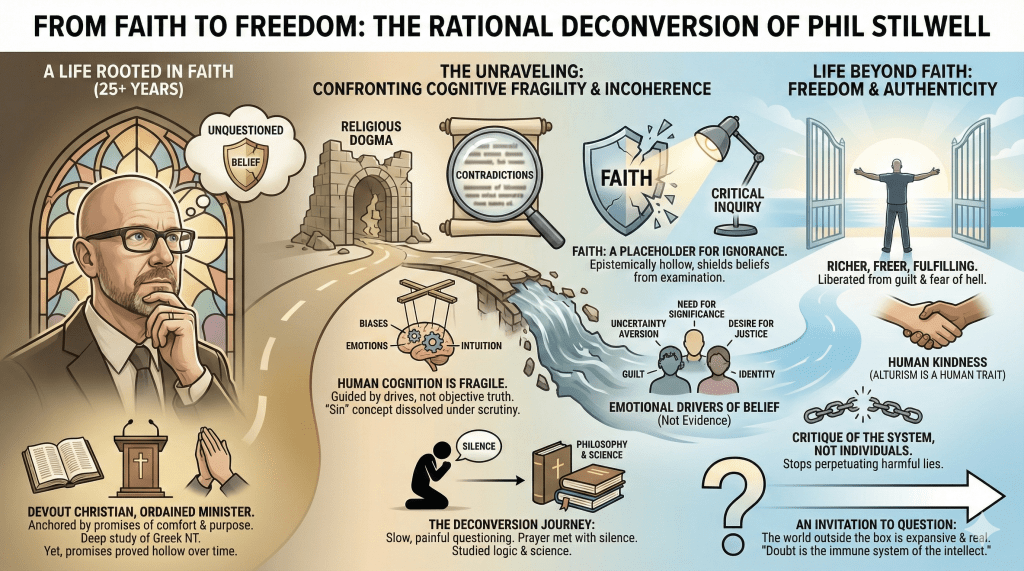

For over 25 years, I lived as a devout Christian, anchored by the promises of verses like, “Come to me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” These words shaped my worldview, my identity, and my relationships. They offered solace in times of doubt, certainty in times of confusion, and purpose in times of struggle. Yet, as comforting as they seemed, these promises, in the long-term, proved hollow. My faith was not lost in a single moment of disillusionment but unraveled slowly over years of searching, questioning, and honest reflection.

I loved many aspects of my Christian life: the sense of community, the focus on kindness, and the feeling of being part of something larger than myself. Yet my intellectual honesty demanded I confront the troubling inconsistencies and assumptions that underpinned my faith. This document is not an attack on Christians as individuals—I know many sincere, kind believers—but rather a critique of the system of belief itself, which relies on flawed premises and perpetuates harm under the guise of virtue.

The Fragility of Human Cognition

The first major step in my deconversion was recognizing the profound limitations of human cognition. We like to think of ourselves as rational beings, yet our brains are often guided by biases, emotional drives, and intuitive leaps that do not correlate with objective truth. Christianity—and most religions—rely on this cognitive frailty, offering answers that feel intuitive but crumble under scrutiny.

Religions worldwide claim exclusive access to truth, often labeling outsiders as rebellious or deluded. Yet when we examine these groups, we find the same confidence, the same fervor, and the same unwavering belief in contradictory doctrines. This is not the result of divine revelation but a reflection of how the human mind clings to certainty, even in the absence of evidence.

As a Christian, I was taught that truth was intuitive for those who “relied on the Lord.” I believed that sin was an inherent part of my nature and that my struggles were evidence of my moral failure. Yet when I stepped outside this framework, I discovered something astonishing: I was not prone to sin. The concept of “sin” itself dissolved when I stopped viewing my actions through the lens of arbitrary, religiously imposed moral codes. What I had labeled as “sin” was often simply human behavior—natural, understandable, and resolvable without shame or guilt.

Faith: A Placeholder for Ignorance

Faith is often held up as the cornerstone of religious life, praised as a virtue in its own right. Yet when we examine it critically, faith reveals itself as epistemically hollow and deeply incoherent. Its definition shifts to suit the needs of its defenders, evading scrutiny and masking the absence of evidence.

Hebrews 11:1 describes faith as “the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen,” but how this is interpreted varies wildly. When I asked pastors and fellow Christians where evidence ends and faith begins, I received as many answers as people I asked. Faith, it seems, is a convenient stop-gap—a tool to shield beliefs from the critical examination that might expose their flaws.

Christians often dismiss the faith of Muslims, Hindus, or others as misplaced, failing to recognize that their own faith operates on the same emotional and psychological foundations. Faith is not a pathway to truth; it is a mechanism for sustaining belief in the absence of evidence. It is, in essence, a placeholder for ignorance.

Emotional Drivers of Belief: Why Faith Feels Necessary

Religious belief does not persist because it is true but because it appeals to deeply ingrained human emotions. These emotional drivers are powerful but ultimately unreliable as indicators of truth. Among the most significant are:

- Aversion to Uncertainty: Humans crave certainty, often more than truth itself. Religion capitalizes on this by offering definitive answers to life’s biggest questions, even when those answers lack evidential support.

- Need for Significance: The promise of cosmic significance—a personal relationship with the creator of the universe—is profoundly compelling. But the emotional appeal of significance does not validate its existence.

- Desire for Justice: Religion offers the comforting notion that justice will ultimately prevail, whether in this life or the next. This emotional need does not, however, serve as evidence for a just deity.

- Yearning for Affection: The promise of unconditional love from a deity fulfills a deep psychological need, but yearning alone does not make it real.

- Sense of Identity: Religious communities provide a powerful sense of belonging, making it difficult to question faith without risking social alienation.

- Guilt: Religious systems co-opt the natural human sense of guilt, tying it to arbitrary moral frameworks. This reinforces adherence to the faith by making its rejection emotionally unbearable.

These emotions are universal, yet they lead to contradictory belief systems across cultures and religions. This universality highlights the subjectivity of religious convictions and their disconnection from objective truth.

A Long Journey of Deconversion

Deconversion is rarely an instantaneous process. For me, it took three years of searching, questioning, and grappling with deeply held beliefs. During this time, I sought answers from pastors, theologians, and fellow Christians, hoping to reconcile my doubts with my faith. I had previously learned Koine Greek and I earnestly read through the Greek New Testament hoping to make sense of the incoherencies. I prayed fervently, begging any god who might exist to reveal themselves to me. I wanted so desperately for the God of my childhood to be real, but there was only silence.

Elaboration:

Throughout my early life, I had been deeply immersed in Christianity. I read through the Greek New Testament more than ten times, a practice that reflected my dedication to understanding the faith at its core. I was ordained as a minister and led several people “to the Lord,” serving actively within evangelical communities. My commitment was sincere, and my devotion to Christ was unwavering.

Yet, despite this, I often encounter claims that I was not the “right kind” of Christian or that I failed to grasp “true Christianity.” Such assertions overlook the depth of my faith and dedication. I approached my beliefs with genuine conviction, striving to live a life in alignment with what I understood to be the teachings of Christ. These experiences shaped not only my identity but also my reflections on what it means to live a life of faith.

The fault was not with the pastors I consulted—they were often kind, thoughtful people—but with the Bible itself, which offered no coherent answers to its contradictions and absurdities. As I studied more deeply, I came to see the Bible not as the inspired word of God but as a flawed and deeply human document, shaped by the cultural and psychological needs of its authors.

Life Beyond Faith: A World of Freedom and Joy

Is my life perfect now? Of course not. But it is infinitely richer, freer, and more fulfilling than it was within the constraints of Christianity. Without the weight of guilt and the fear of eternal damnation, I am free to explore, learn, and grow authentically. My happiness does not stem from the absence of problems but from the freedom to face those problems without the added burden of religious dogma.

Contrary to Christian stereotypes, I am not “filling up my godless life with sin.” The idea that a life without God must devolve into debauchery is a projection of religious assumptions, not a reflection of reality. In truth, the world is full of beauty, meaning, and opportunity that have nothing to do with religion.

Altruism, compassion, and kindness are not exclusive to Christianity. These are human traits, deeply rooted in our social nature. I have seen this in my godless friends, who go out of their way to help others, support the homeless, and offer kindness without expectation of divine reward. Their actions are not “Christian behaviors” but human behaviors.

Christianity’s Harmful Lies

I do not hesitate to express my disdain for Christianity—not for Christians as individuals, but for the lies perpetuated by the faith itself. Christianity traps its adherents in cycles of guilt and fear, preventing them from experiencing the full satisfaction of a life grounded in reality. It is not a sin to question whether Jesus and Jehovah are products of human imagination. If such questioning is a sin, then I hope more people will “fall into sin” and discover the freedom and joy that await beyond the confines of faith.

To those who propagate these lies, whether out of ignorance or intent, I offer no excuses. The harm you perpetuate—the sorrow, fear, and stunted potential—is unjustifiable.

Conclusion: An Invitation to Question

Life beyond Christianity is not perfect, but it is vibrant, fulfilling, and deeply satisfying. I no longer seek validation from an imaginary deity or live in fear of hell. Instead, I find meaning in the richness of human experience, the pursuit of knowledge, and the bonds we create with one another.

To those still trapped in the myths of Jesus and Jehovah, I encourage you to take the courageous step of questioning your assumptions. You may find, as I have, that the world outside the small box of faith is far more expansive, beautiful, and real than you ever imagined.

Explore for yourself many of the questions I asked during my journey in the Considerations section here on Free of Faith.

Supplemental Explanations made in Various Dialogues:

The Long Undoing of Certainty

At the beginning of my adult life as a Christian, I was utterly convinced that if I studied Scripture diligently and honestly, the truth of God would grow ever clearer—more intimate, more undeniable. That’s not what happened. The deeper I went, the more I encountered incoherence. In earnest desperation, I turned to pastors and mentors for clarity. None had answers—only the repeated counsel to “have faith,” meaning to go on believing in spite of what reason exposed. I lacked formal training in epistemology then, but I knew enough to recognize that such “faith” was not honesty. It was make-believe in the service of emotional comfort.

It became obvious in how young converts are treated: questions are spiritualized into “doubts,” and doubts are pathologized as instability. James’s “waves of the sea” metaphor was pressed upon me as proof that questioning truth claims made one “double-minded.” Over time, those same passages became mirrors of my growing disquiet. Christianity’s epistemic foundation was full of holes, and the injunction to trust rather than think widened every one of them.

Still, I wasn’t eager to lose the idea of God. I spent another year pleading for any genuine deity to reveal itself—any evidence, any signal that there was someone on the other end. None came. What did come was an unexpected realization: the “hopeless, meaningless life” I’d been warned of was nowhere to be found. The day I stopped fearing divine abandonment, the world became luminous with wonder. I returned to university, studied philosophy and science, and discovered that genuine understanding—unassisted by the supernatural—was far more awe-inspiring than the rhetoric of revelation. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom”? No. The beginning of wisdom is curiosity freed from fear and faith.

The doctrine of Hell had long haunted me, but even that fear dissolved once examined. The notion of an all-loving, all-just being sentencing finite creatures to infinite torment was a moral and logical absurdity. And the apologists’ evasions—contradictory interpretations of Romans 1, Hebrews 11, or the “image of God”—only deepened the incoherence. I wanted to believe. But faith demanded pretending to know what one does not and cannot know. That pretense, I came to see, was intrinsically dishonest—an epistemic fraud no actual God worthy of the name would reward. Yet it is precisely that fraud that fills pulpits every Sunday.

As a child of seven, I was assured that God had “heard” my whispered prayer for salvation, despite my uncertainty. That same psychological manipulation repeats endlessly: belief is declared valid by those who later deny it ever existed once one leaves the fold. After 25 years of unwavering devotion, I am told I was “never truly saved.” But if the depth of conviction defines salvation, I was as saved as anyone who ever preached a sermon.

I once led others to the faith—and that is one chapter of my life I deeply regret. I was passing along the very irrationality that entrapped me. For years now, I’ve been working to reverse that harm, helping others navigate out of faith through reasoned discourse. Watching minds awaken to rational inquiry has been one of the greatest joys of my life.

I still welcome any argument that could change my mind, but to date, I’ve encountered mostly hostility and hollow apologetics. I could be wrong—but conviction without evidence will never persuade me again. I’m building tools to help young believers sharpen their reasoning, whether that leads them to better apologetics or to the freedom of doubt. Doubt, after all, is not a disease; it’s the immune system of the intellect.

I’m also writing a couple of books examining the psychology and (il)logic of belief. The discussions in this group—at once defensive and revealing—serve as an invaluable laboratory for understanding faith’s tenacity. The apologists have their work cut out for them.

A recent, related post.

From Ordination to Honest Doubt: My Exit From Christianity

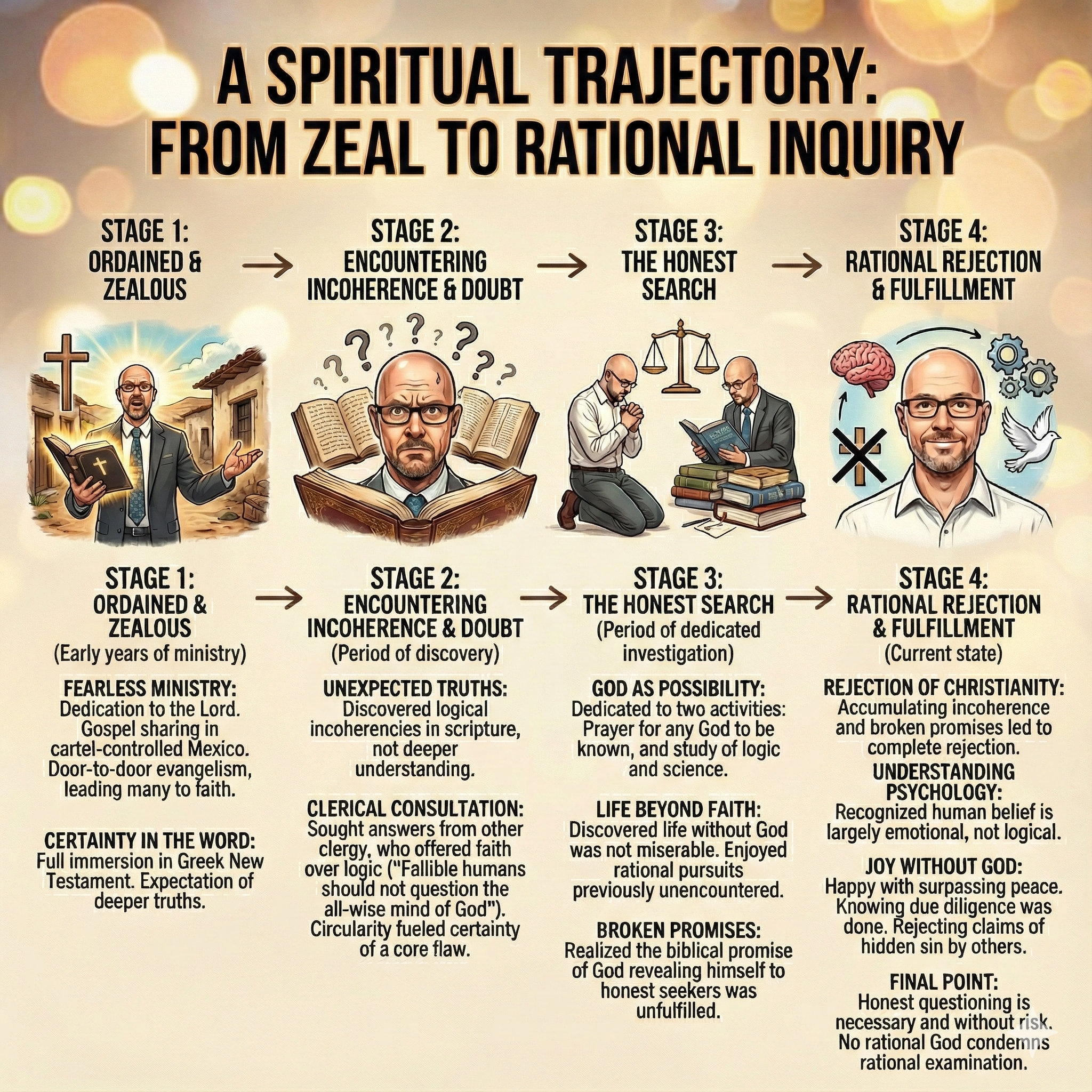

After I was ordained in the early 80s, I dedicated myself fully to the Lord and fearlessly shared the Gospel deep in the cartel-controlled regions of Mexico. I did extensive door-to-door evangelism and led many to the Lord. During this time, I was fully certain the truth was in the Word. I immersed myself in the Greek text of the New Testament and was certain I would uncover deeper truths.

I did—but they were not what I was expecting. I uncovered logical incoherencies I could not resolve. Christians around me who were fully cognizant of the same incoherencies were mustering up the faith to shrug off the doubts. I couldn’t.

I was also very certain that a God of rationality would not condemn honest, rational questioning of his existence and description. So I took my Bible around to other clergy in my city and asked whether they could provide satisfactory answers to the list of incoherencies I had encountered. They could not. They, too, had sufficient faith to push aside those troubling questions and simply say:

“We’ll find understanding in the next life at the feet of Jesus. Fallible humans should not question the all-wise mind of God.”

That circularity only made me more certain that something was deeply flawed at the core of Christianity. Yet I had loved the life of faith I had lived for 25 years, and I was not about to say that all those years in communion with the Lord were merely emotional experiences. I was still certain there could be no joy or peace that surpassed the joy and peace the Lord can give. I was certain that a life without God would be miserable.

But I was so determined to find the unadulterated truth that I allowed myself to honestly treat God as only a possibility.

For two years, I devoted myself to two activities:

✓ I spent hours on my knees asking any actual God to make himself known.

✓ At the same time, I studied introductory logic and science.

One thing quickly became clear: life without a God was not miserable at all. I thoroughly enjoyed the philosophy, logic, and science I was learning—things I’d never encountered while within Christianity. While the Bible doesn’t explicitly say a Godless life will be miserable, that’s what I had been told for 25 years, only to discover it was false.

It was about two years after spending much time on my knees, asking for any God to make himself known, that I realized the promise in the Bible—that the Christian God would reveal himself to all those who honestly seek him—was wrong as well.

So, slowly, with accumulating logical incoherence and broken promises in the Bible, I found myself rejecting Christianity completely. I also came to see more clearly that human psychology is largely emotional, and that humans can emotionally talk themselves into nearly any type of belief—even when those beliefs are logically incoherent.

One of the most disappointing things is to now hear Christians who do not know my life claim that I was never a Christian, and that when I was on my knees for those two years, I was harboring some type of pride or personal sin—causing God to remain hidden. The Christians in my local church never suggested that, having known me and my ministry for so many years. But those who did not know me did not hesitate to do so.

So here I am: without a God. Happy. With joy and peace that truly surpass even what I felt from the Lord—knowing I have done due diligence to ensure any actual God could make himself known.

There may be some of you who are at different stages of seeking. There is one very important point I want to make that will serve you well:

✓ Don’t let anyone convince you that honestly questioning a God would be inappropriate. It is not.

✓ In fact, it is necessary.

✓ And it is without risk.

No actual God of the universe would condemn your use of the rational mind he gave you to rationally examine his alleged claims.

Feel free to push back on this—but do so knowing that I, too, pushed back for many years against those who dared suggest God could be questioned.

Leave a comment