The Dimensions of Belief:

A Rational and Soteriological Inquiry

Belief is a cornerstone of human cognition, and its rational assessment hinges on three key dimensions: degree, quality, and object. These dimensions apply universally across domains of thought, serving as the foundation for evaluating beliefs about the natural world, personal decisions, and theological claims. In soteriology, where belief is deemed the gateway to redemption, these dimensions acquire particular gravity. This essay explores the universal application of these dimensions, then delves into their implications for soteriology.

The Three Dimensions of Rational Belief

1. The Degree of Belief

Definition: How much belief is sufficient to act or hold a position as rational?

Belief exists on a spectrum, from weak suspicion to unwavering certainty. Rationality demands that the degree of belief correspond proportionally to the strength of the evidence supporting it. Misalignment leads to overconfidence or unwarranted skepticism, both of which hinder sound judgment.

Example 1: Meteorology

A person planning a picnic might believe it will not rain based on a weather forecast. However, if the forecast changes to a 70% chance of rain, rationality demands a reassessment of belief and adjustments to plans, such as bringing an umbrella or rescheduling.

Example 2: Investment Decisions

An investor considering a new stock must evaluate the evidence for its potential growth. A modest belief based on limited data may justify a small investment, while strong evidence might warrant a significant financial commitment. Believing too strongly in the stock without adequate data risks financial loss.

2. The Quality of Belief

Definition: Does the belief proportionally reflect the degree of evidence available?

The quality of belief pertains to its alignment with evidence. A high-quality belief does not exceed or fall short of what the evidence warrants. Quality ensures that beliefs are neither overly optimistic nor excessively doubtful.

Example 1: Medical Diagnoses

A doctor faced with a patient’s symptoms might initially believe the condition is minor. However, new test results indicating serious abnormalities should shift the belief toward a more severe diagnosis. A failure to align belief with evidence could jeopardize the patient’s treatment.

Example 2: Navigating Trust

Consider trusting a friend to repay a loan. If the friend has a history of reliability, belief in their repayment should be strong. However, if the friend has defaulted on previous loans, belief in repayment should be proportionally weaker, reflecting the diminished quality of the evidence.

3. The Object of Belief

Definition: What is the specific proposition or set of propositions being believed?

Rational belief requires a clear and well-defined object. Ambiguity about what is believed undermines the rationality of the belief, as it prevents meaningful evaluation and alignment with evidence.

Example 1: Scientific Hypotheses

A scientist testing a hypothesis about climate change must clearly define the hypothesis to assess whether the evidence supports it. A belief in “some kind of warming” without specifics lacks the precision necessary for rational inquiry.

Example 2: Consumer Decisions

A person purchasing a smartphone might believe it has excellent battery life. However, this belief must be specific—e.g., “the phone lasts 12 hours on a full charge during normal use”—to guide the purchase rationally. A vague belief leads to ill-informed decisions.

Application to Soteriological Belief

When applied to soteriology, these dimensions illuminate the challenges of defining redemptive belief. If belief is central to salvation, then its degree, quality, and object must be explicitly defined to avoid ambiguity and injustice.

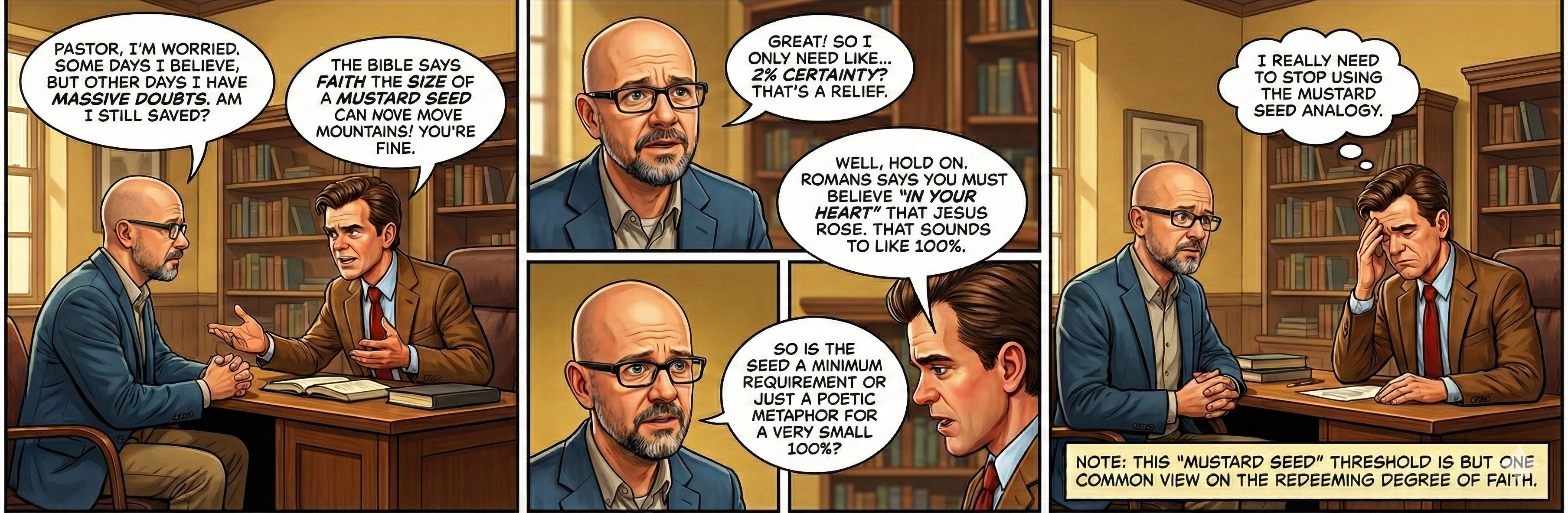

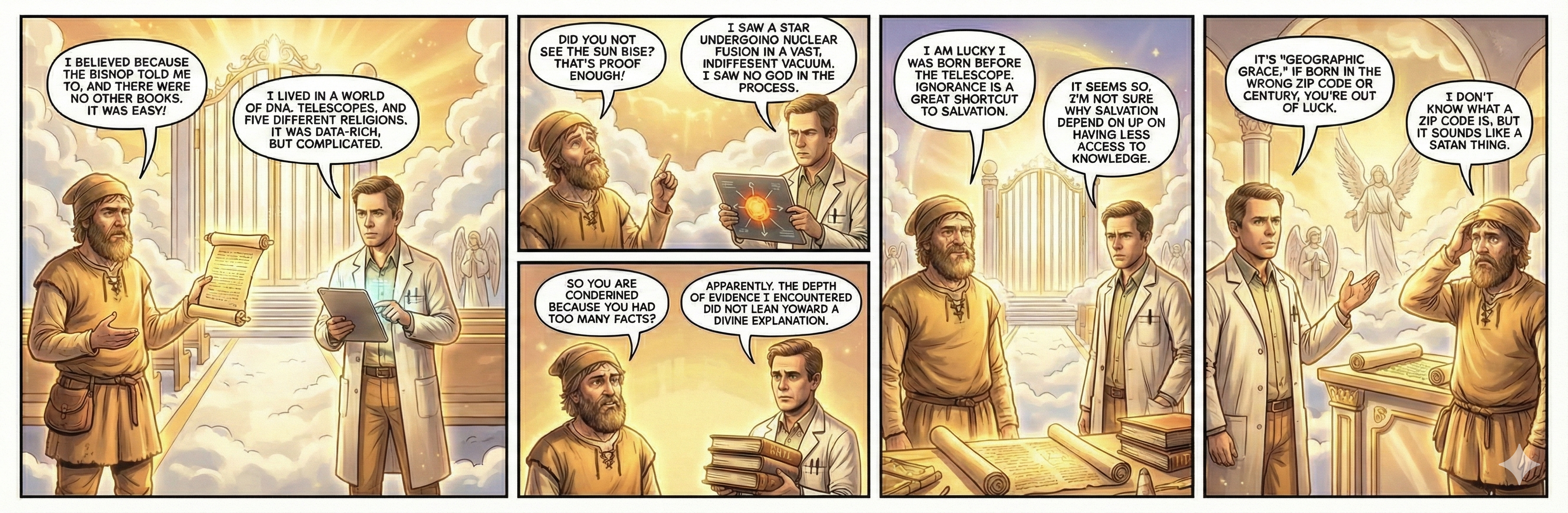

1. Degree of Belief in Soteriology

The degree of belief concerns the threshold of faith required for redemption. Is mere acknowledgment of the Gospel sufficient, or does belief require unwavering conviction? This question remains unresolved in many theological traditions, leaving believers uncertain about their standing.

Example 1: The “Mustard Seed” Faith

Biblical texts such as Matthew 17:20 suggest that faith “the size of a mustard seed” is sufficient for redemption. If true, this sets a low threshold, potentially redeeming even those with significant doubts.

Example 2: Absolute Conviction

Other interpretations imply that unwavering belief in the Gospel is necessary for salvation. For example, Romans 10:9 states that salvation depends on confessing and believing “in your heart” that Jesus rose from the dead. This raises the bar for the degree of belief required.

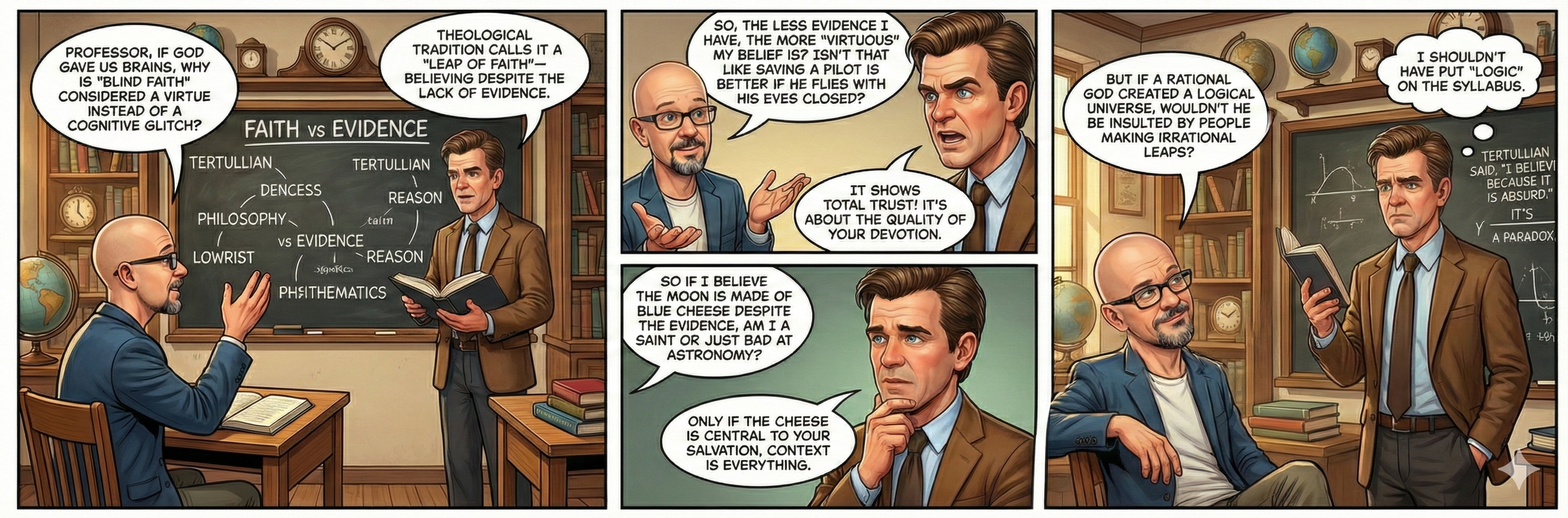

2. Quality of Belief in Soteriology

The quality of belief addresses whether faith aligns with the evidence available. Many traditions exalt faith that surpasses evidence, framing it as a virtue, yet this raises questions about whether irrational faith would be honored by a rational deity.

Example 1: Faith in Miracles

A believer might affirm the resurrection of Jesus despite scant empirical evidence. If this belief disregards the principle of proportionate evidence, it may be considered irrational. Would a rational God honor such faith, or require belief grounded in stronger evidence?

Example 2: The Leap of Faith

Some believers advocate for a leap of faith, where conviction is reached despite insufficient evidence. For instance, affirming divine intervention in personal hardships without objective proof raises questions about whether such belief aligns with the evidence or undermines rationality.

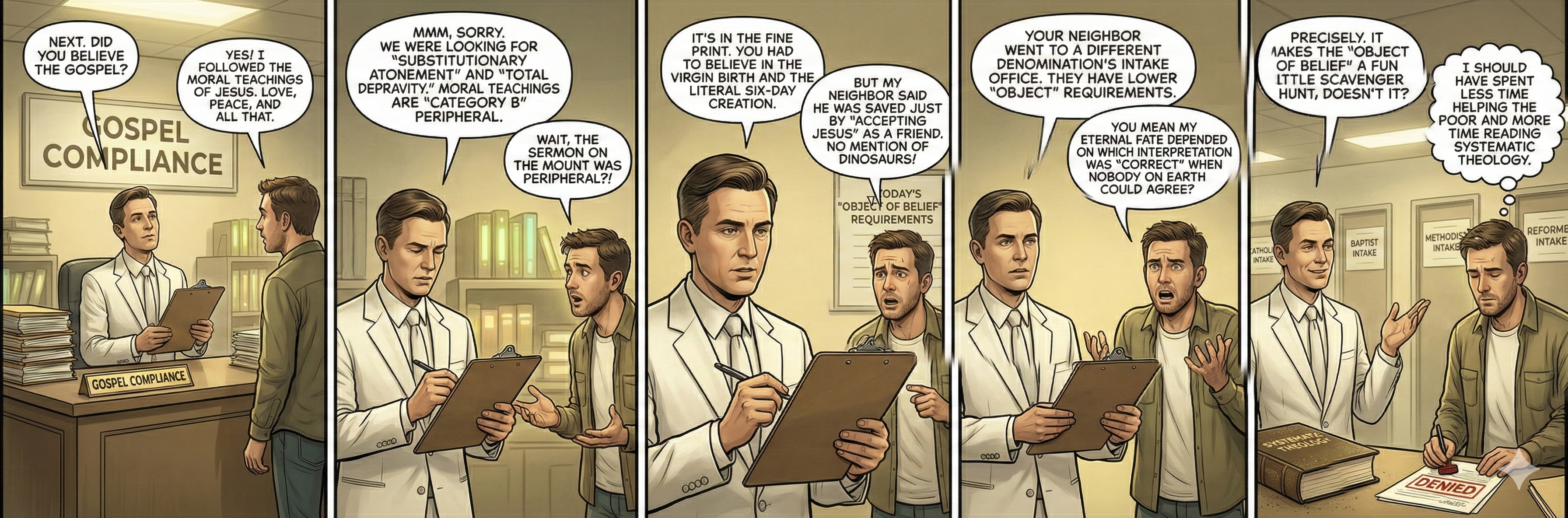

3. Object of Belief in Soteriology

The object of belief in soteriology is the Gospel, but what constitutes the “essential” elements of the Gospel? Theological traditions differ, creating ambiguity about what must be believed to attain redemption.

Example 1: Christology

Some traditions emphasize belief in Christ’s divinity, the Trinity, and the resurrection as essential. Others focus on simpler tenets, such as Christ’s moral teachings or his role as a savior. This variability leaves the object of belief unclear.

Example 2: Childhood Faith

A child who believes in Jesus because “Mommy says so” likely lacks understanding of complex doctrines like atonement or original sin. Is such belief sufficient for redemption, or must the believer grasp more nuanced theological concepts? The lack of consensus on the object of belief compounds the problem.

Implications of Vagueness in Redemptive Belief

The absence of clear definitions for the dimensions of belief in soteriology creates several issues:

- Injustice: Without defined thresholds for belief, redemption appears arbitrary. A person with weak faith might be saved, while another with stronger but incomplete faith might not.

- Division: Disputes over essential doctrines fragment religious communities, fostering division and conflict.

- Disillusionment: Rational seekers may interpret this ambiguity as incoherence, driving them away from faith rather than toward it.

Toward a Coherent Soteriology

For soteriology to be coherent, it must explicitly define the dimensions of redemptive belief:

- Degree: Clarify the threshold of belief required for redemption.

- Quality: Determine whether belief must align with evidence or if faith beyond evidence is acceptable.

- Object: Specify the essential elements of the Gospel that must be believed, ensuring clarity and doctrinal consistency.

Conclusion

The dimensions of belief—degree, quality, and object—are fundamental to both rational thought and theological frameworks. Applied universally, they ensure coherence and alignment with evidence. In soteriology, their precise definition is vital to avoid injustice and ambiguity. Without such definitions, the foundation of redemptive belief remains unsteady, challenging both the rationality and fairness of theological claims.

By rigorously addressing these dimensions, theological systems can bridge the gap between reason and faith, creating a framework that respects intellectual integrity and fosters genuine understanding. Such clarity is essential for a credible and coherent soteriology.

The Dimensions of Belief and Their Relevance to Final Judgment

1. Degree of Belief

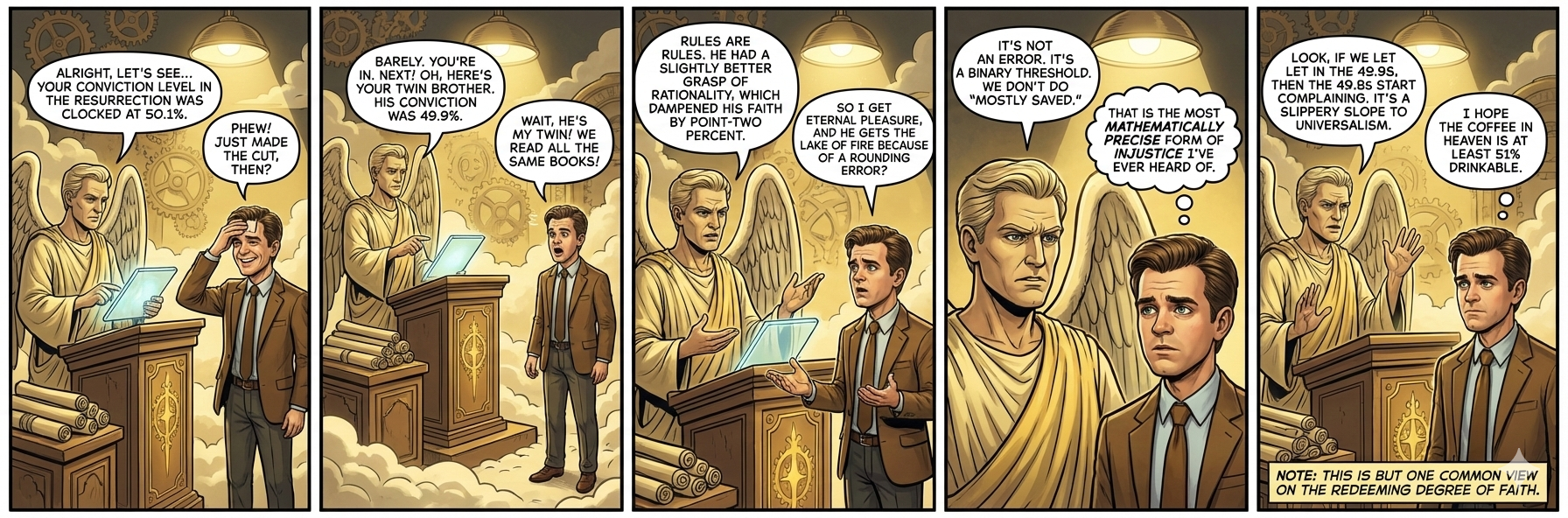

Definition: How much belief is sufficient to warrant salvation?

The degree of belief exists on a spectrum, ranging from weak suspicion to absolute certainty. Biblical texts often fail to clarify the threshold of belief required for salvation, leaving critical questions unanswered: Is minimal belief sufficient, or must one have unwavering conviction? Without specifying the threshold, a binary judgment system becomes arbitrary and unjust.

Example 1: Tentative vs. Absolute Belief

A person might tentatively believe in the Gospel, influenced by limited exposure or personal doubt. Another might hold absolute conviction after years of study and spiritual experience. Treating both individuals identically under final judgment ignores the gradient nature of belief.

Example 2: Belief Over Time

Belief often fluctuates throughout a person’s life. A believer might experience periods of doubt or even unbelief before returning to faith. Is final judgment based on the strongest point of belief, the weakest, or some average over time? The binary model fails to account for this dynamism.

Logical Incoherence:

If belief exists on a spectrum, any binary cutoff for salvation or condemnation is necessarily arbitrary. A person with belief just below the threshold would face eternal punishment, while someone barely above it would receive eternal reward—despite their beliefs being nearly indistinguishable. This creates an unjust and illogical system.

2. Quality of Belief

Definition: Does the belief proportionally reflect the degree of evidence available?

The quality of belief addresses whether an individual’s belief aligns with the evidence they have encountered. High-quality belief arises when belief is proportionate to the evidence, while low-quality belief involves overconfidence or irrational leaps of faith. A binary judgment system ignores this crucial dimension, treating all belief as either sufficient or insufficient, regardless of its rationality.

Example 1: Evidence and Opportunity

Consider two individuals: one grows up in a religious environment with abundant access to Gospel teachings, while the other lives in a remote region with no exposure to Christianity. The first individual might develop strong belief based on cultural reinforcement, while the second remains a non-believer due to lack of evidence. Judging both individuals under the same binary framework disregards the role of evidence in shaping belief.

Example 2: Irrational Faith

A person might claim absolute belief in the Gospel but base this belief on emotional manipulation, social pressure, or fear of hell rather than a reasoned evaluation of evidence. Another might hold tentative belief rooted in genuine intellectual engagement. The binary system fails to distinguish between high- and low-quality belief, treating both equally.

Logical Incoherence:

If a rational God values proportionality and evidence-based reasoning, rewarding irrational leaps of faith undermines the coherence of divine judgment. Conversely, punishing individuals for failing to believe in the absence of sufficient evidence contradicts principles of fairness and rationality.

3. Object of Belief

Definition: What is the specific proposition or set of propositions being believed?

The object of belief in biblical soteriology is often described as “faith in the Gospel,” but the precise elements of this faith are subject to interpretation. Must one believe in the resurrection, the Trinity, or original sin? What about less central doctrines, such as the virgin birth or the inerrancy of Scripture? The lack of clarity on the required object of belief introduces significant ambiguity into the binary judgment model.

Example 1: Doctrinal Disagreements

Christian denominations differ widely in their understanding of essential doctrines. A Catholic may emphasize the authority of the Church and sacraments, while a Protestant focuses on sola fide (faith alone). If final judgment hinges on the correctness of one’s beliefs, how can individuals be fairly judged when the object of belief is not universally agreed upon?

Example 2: Partial Understanding

A child may believe that Jesus is “a good man who loves people” without grasping complex theological concepts like the atonement or the hypostatic union. Is this belief sufficient for salvation? The binary system offers no mechanism to account for partial or incomplete understanding of the object of belief.

Logical Incoherence:

If salvation depends on belief in specific doctrines, the failure to clearly define the required object of belief renders judgment arbitrary. Moreover, the diversity of interpretations among Christians makes it impossible to determine which set of beliefs, if any, is the correct standard for judgment.

Broader Implications of a Binary Judgment System

1. The Problem of Continuity

The binary nature of final judgment creates an illogical discontinuity. A person with 49% certainty in the Gospel is condemned, while one with 51% certainty is saved—despite their beliefs being nearly identical. Such discontinuity is antithetical to the gradient nature of belief.

2. The Problem of Epistemic Luck

Belief is often influenced by factors beyond an individual’s control, such as cultural background, upbringing, and access to evidence. A binary system rewards or punishes individuals based on factors that may have little to do with their own choices or reasoning.

3. The Problem of Ambiguity

The absence of clear thresholds for the degree, quality, and object of belief creates ambiguity that undermines the justice of final judgment. How can individuals be held accountable for failing to meet standards that are not explicitly defined?

Toward a More Rational Framework

A coherent system of divine judgment would need to address the dimensions of belief explicitly:

- Degree: Define the precise threshold of belief required for salvation and account for fluctuations over time.

- Quality: Evaluate belief based on its alignment with evidence, rewarding proportional and rational belief while considering the evidence available to each individual.

- Object: Clearly specify the essential components of the Gospel that must be believed, resolving doctrinal ambiguities.

This framework would respect the complexity of belief and ensure that judgment is based on clear, fair, and rational criteria.

Conclusion

The binary model of biblical final judgment collapses under the weight of the nuanced dimensions of belief. The gradient nature of belief (degree), the importance of evidence-based reasoning (quality), and the ambiguity of required doctrines (object) expose the logical incoherence of a system that categorizes individuals as either saved or condemned. Without addressing these dimensions, biblical soteriology remains a simplistic and unjust framework, unable to accommodate the complexities of human belief.

A rational and fair system of judgment would necessarily account for these dimensions, aligning divine justice with the realities of human cognition. Until such a framework is articulated, the binary nature of final judgment remains an indefensible oversimplification.

The Free of Faith Companion Podcast Episode:

Argument 1: The Gradient Nature of Belief Makes Binary Judgment Arbitrary

Syllogistic Form:

- All beliefs exist on a spectrum (gradient) of conviction, from weak suspicion to absolute certainty.

- A binary judgment system evaluates beliefs as either sufficient or insufficient for salvation, ignoring intermediate degrees of belief.

- Arbitrary thresholds for salvation are unjust because nearly identical beliefs can result in opposite outcomes.

- Therefore, binary judgment based on belief is logically incoherent.

Symbolic Logic Form:

Argument 2: The Quality of Belief Invalidates Binary Judgment

Syllogistic Form:

- Rational belief aligns proportionally with the evidence available to the believer.

- A binary judgment system rewards belief without considering its alignment with evidence.

- Rewarding irrational leaps of faith or punishing those who lack sufficient evidence is unjust.

- Therefore, binary judgment based on belief quality is logically incoherent.

Symbolic Logic Form:

Argument 3: The Object of Belief is Ambiguous

Syllogistic Form:

- The object of belief (e.g., the Gospel) must be clearly defined for fair judgment.

- Different interpretations of the Gospel lead to varying objects of belief among individuals.

- Judging individuals based on unclear or inconsistent objects of belief is unjust.

- Therefore, binary judgment based on the object of belief is logically incoherent.

Symbolic Logic Form:

Overall Argument: Binary Judgment is Logically Incoherent

Syllogistic Form:

- Belief has three dimensions: degree, quality, and object.

- A binary judgment system fails to account for the gradient nature of degree, the proportionality of quality, and the ambiguity of the object.

- Systems that fail to account for these dimensions are arbitrary and unjust.

- Therefore, binary judgment based on belief is logically incoherent.

Symbolic Logic Form:

Definitions for Symbolic Logic

- Belief Variables:

: The degree of belief held by individual

, where

.

- Example: If

, individual

holds a strong belief in the proposition.

- If

, individual

has a weak belief.

- Example: If

- Threshold for Salvation:

: The cutoff threshold for belief required for salvation.

- If

, individual

is saved (

).

- If

, individual

is not saved (

).

- If

- Saved Status:

: Individual

is saved (redeemed in a binary judgment system).

: Individual

is not saved (condemned in a binary judgment system).

- Gradient Differences:

: A negligible difference in belief between two individuals.

- Example: If

, the beliefs of

and

are nearly identical.

- Example: If

- Quality of Belief:

: The quality of belief held by individual

, which reflects the alignment of belief with available evidence.

- Defined as

, where

is the evidence accessible to individual

.

- Defined as

- Evidence:

: The evidence available to individual

that influences the quality of their belief.

- Example: A person with abundant evidence for a proposition may hold a higher-quality belief (

) than someone with limited evidence.

- Example: A person with abundant evidence for a proposition may hold a higher-quality belief (

- Object of Belief:

: The object of belief for individual

, representing the specific proposition or doctrine being believed.

- Example:

could represent belief in the Trinity, resurrection, or moral teachings of Christ.

- Example:

- Set of Doctrines:

: The set of all possible doctrines or propositions associated with salvation.

- Example:

, where

represents specific beliefs (e.g., resurrection, virgin birth).

- Example:

- Just System:

- A just system evaluates individuals fairly, considering the dimensions of belief (degree, quality, and object) without arbitrary thresholds.

- Judgment Function:

: The judgment function that determines whether individual

is saved (

) or not saved (

).

- In a binary system:

if belief meets predefined criteria.

- In a binary system:

Comprehensive Questions for Each Dimension of Belief in Biblical Redemption

1. Degree of Belief

Definition: How much belief is sufficient for redemption?

- What is the minimum threshold of belief required for salvation? Is mere acknowledgment of the Gospel sufficient, or is deep conviction necessary?

- Can redemption occur with partial belief, such as belief in some but not all aspects of the Gospel?

- Is doubt compatible with saving belief? If so, how much doubt is permissible?

- How does the degree of belief required vary across different individuals, such as new believers, children, or lifelong adherents?

- Can belief fluctuate over time and still be sufficient for redemption, or must it remain consistently strong?

- Does the degree of belief required differ for people exposed to varying levels of evidence (e.g., someone living in a remote area versus someone with access to Christian teachings)?

- How does biblical redemption accommodate those who have strong emotional belief but weak intellectual understanding?

2. Quality of Belief

Definition: Does the belief proportionally reflect the degree of evidence available?

- Does God honor belief that exceeds the evidence, or must belief proportionally align with the evidence available to the believer?

- Can a person be redeemed if they accept the Gospel through a “leap of faith” without sufficient evidence?

- Is it rational for a believer to maintain conviction in the Gospel despite significant contrary evidence?

- How does God evaluate beliefs held under cultural, emotional, or social pressures rather than through personal evidence-based reasoning?

- Is belief grounded in fear of punishment (e.g., hell) considered high-quality belief, or does it need to stem from understanding and conviction?

- Does the Bible encourage believers to critically examine evidence, or is uncritical acceptance of faith sufficient for redemption?

- What is the role of miracles, personal experiences, or testimonies in contributing to the quality of belief?

3. Object of Belief

Definition: What is the specific proposition or set of propositions being believed?

- What are the essential components of the Gospel that must be believed for salvation? For example, is belief in the Trinity, resurrection, or original sin necessary?

- Can a person who has an incomplete or erroneous understanding of Christ’s divinity or mission still be redeemed?

- Is belief in the literal truth of biblical accounts (e.g., the virgin birth, Noah’s ark) required, or are these considered peripheral to salvation?

- How does the object of belief differ for children, the uneducated, or those with limited access to theological teachings?

- Is belief in Christ’s moral teachings (e.g., love, forgiveness) sufficient, or must one also believe in specific doctrinal points (e.g., atonement, substitutionary sacrifice)?

- Does belief in the Gospel require specific denominational interpretations, or is a generalized faith in Christ sufficient?

- How does God evaluate beliefs about Jesus held in ignorance of other theological concepts, such as the Trinity or predestination?

Additional Meta-Questions Across Dimensions

- How can Christians ensure they accurately communicate the degree, quality, and object of belief necessary for redemption to others?

- How should believers navigate situations where their interpretation of the Bible conflicts with traditional doctrines about belief and redemption?

- What mechanisms, if any, exist in biblical theology to clarify ambiguities surrounding these dimensions of belief?

These questions aim to address the unresolved ambiguities in soteriology, providing a framework for theological clarity and rational inquiry.

The Illogic of Rigidly Categorizing Belief:

The Inadequacy of Labels like “Atheist,” “Agnostic,” “Theist,” and “Deist”

Belief is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon, influenced by the interplay of evidence, experience, and interpretation. Despite this complexity, society often seeks to impose rigid labels such as atheist, agnostic, theist, and deist onto individuals. These labels, while convenient, fail to capture the nuanced dimensions of belief, particularly the degree, quality, and object of belief, which govern rational thought. This essay explores why these labels are inadequate, demonstrating that belief is inherently gradient and resists oversimplification.

The Dimensions of Belief

Before addressing the limitations of rigid categorizations, it is essential to understand the three dimensions of belief—degree, quality, and object—and how they operate in human cognition.

Degree of Belief

The degree of belief refers to how strongly a proposition is accepted, ranging from tentative suspicion to absolute conviction. Few individuals hold unwavering certainty about metaphysical claims, even among self-identified theists or atheists. For example, an atheist might lack belief in God but still hold a non-zero credence that God could exist.

Quality of Belief

The quality of belief pertains to its proportional alignment with evidence. A belief that is weakly supported by evidence but strongly held is irrational. This dimension highlights the epistemic responsibility of ensuring that the strength of belief reflects the weight of evidence.

Object of Belief

The object of belief refers to the specific proposition being believed. For instance, belief in a “God” can vary drastically depending on whether the believer envisions a deistic creator, a personal deity, or an abstract principle of order.

These dimensions reveal that belief is not a binary state but a gradient phenomenon, one that resists simplistic categorization.

The Limitations of Traditional Labels

1. Atheist

An atheist is often defined as someone who lacks belief in any god. However, this label obscures critical nuances:

- Degree of Belief: A strong atheist who asserts “God does not exist” with high conviction differs fundamentally from a weak atheist who simply withholds belief in the absence of evidence.

- Object of Belief: The concept of “God” varies widely. An atheist might reject the God of the Bible but remain open to abstract deistic notions or pantheistic interpretations.

The term “atheist” conflates these variations, failing to capture the individual’s specific stance on the proposition and their level of certainty.

2. Agnostic

The label “agnostic” suggests uncertainty or suspension of judgment about God’s existence. However, it provides little insight into the degree, quality, or object of belief:

- Degree of Belief: Agnostics can range from those leaning toward theism (e.g., “I believe there might be a God but can’t know for sure”) to those leaning toward atheism (e.g., “I doubt God exists but remain open to evidence”).

- Quality of Belief: An agnostic’s openness to evidence might vary widely; some may actively seek clarity, while others may remain indifferent.

- Object of Belief: Agnostics may be unsure about specific theological claims (e.g., a personal God) while being confident about rejecting others (e.g., biblical literalism).

As a result, “agnostic” often masks more than it reveals about an individual’s epistemic stance.

3. Theist

Theism, broadly defined as belief in at least one god, encompasses a vast spectrum of beliefs:

- Degree of Belief: Some theists hold absolute certainty in God’s existence, while others maintain a tentative belief informed by personal experiences or philosophical arguments.

- Object of Belief: The term “theist” fails to distinguish between belief in a personal God (e.g., Yahweh or Allah) and belief in a more abstract deity (e.g., Spinoza’s God). It also does not differentiate between polytheistic and monotheistic traditions.

The label “theist” is overly broad and ignores the diversity of theological interpretations.

4. Deist

Deists, who believe in a non-intervening creator, are similarly grouped under a single umbrella that erases important distinctions:

- Degree of Belief: A deist might hold firm conviction in a distant creator or merely entertain it as a plausible hypothesis.

- Quality of Belief: Some deists base their belief on philosophical reasoning, while others rely on intuition or personal experience.

- Object of Belief: The concept of a deistic god varies significantly, from an impersonal force to a vaguely defined architect of the universe.

The term “deist” captures only a fraction of the complexity within this worldview.

Why Belief Defies Rigid Categorization

1. Belief is Gradient

Belief operates on a continuum, not a binary. Few individuals are entirely certain or uncertain about metaphysical propositions, yet the labels “theist” and “atheist” imply such extremes. Recognizing belief as a gradient allows for more accurate representation of individual perspectives.

Example:

A person might reject organized religion but hold a non-zero credence in the existence of a higher power. Labeling this person as an atheist erases the complexity of their belief.

2. Belief is Multi-Dimensional

Labels fail to account for the interplay of degree, quality, and object. A strong, high-quality belief in a loosely defined God differs fundamentally from a weak, low-quality belief in a specific deity.

Example:

Two individuals might identify as theists, but one believes in a personal God based on philosophical arguments, while the other follows a polytheistic tradition rooted in cultural heritage. A single label cannot encompass these differences.

3. Belief is Context-Dependent

Belief is shaped by cultural, historical, and personal contexts. Terms like “theist” and “agnostic” lack the flexibility to reflect the influence of these factors.

Example:

A theist in a predominantly Christian society may hold different assumptions about God than a theist in a polytheistic tradition. Context shapes not only the object of belief but also the degree and quality.

Toward a More Nuanced Framework

Instead of relying on rigid categories, belief should be evaluated using a framework that incorporates its multidimensional nature:

- Degree: What is the strength of the belief? Is it tentative or absolute?

- Quality: Does the belief align proportionally with the evidence?

- Object: What specific proposition is being believed?

This approach respects the complexity of belief and allows for a more precise understanding of individual perspectives.

Conclusion

Rigid labels such as “atheist,” “agnostic,” “theist,” and “deist” oversimplify the nuanced dimensions of belief. By ignoring the degree, quality, and object of belief, these categories obscure more than they reveal, fostering misunderstanding and reducing complex epistemic stances to binary or vague classifications.

A more nuanced framework—one that recognizes belief as gradient, multi-dimensional, and context-dependent—provides a clearer and more rational way to engage with individuals’ perspectives. Such an approach not only enhances intellectual discourse but also promotes a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human belief.

Leave a comment