Consider the Following:

Summary: This post challenges the notion that religious belief reflects free will by highlighting how cultural and geographical factors overwhelmingly shape belief systems, making true choice unlikely. It argues that if a just and omnipotent God existed, He would provide everyone with an equal opportunity to know Him, but the uneven global distribution of beliefs suggests otherwise.

Imagine if someone claimed that all children possess complete freedom in selecting the language they speak. We know this isn’t true; children largely adopt the language of their immediate surroundings, learning from the adults and communities they grow up in. This scenario draws a striking parallel to religious belief: just as language is culturally inherited, religious belief systems are often passed down through social and familial lines. Rarely do we encounter instances where a child raised in a Christian community independently selects Islam or vice versa, and this trend highlights how social conditioning and environmental factors heavily shape one’s religious identity.

If religious belief were purely a matter of personal choice or free will, wouldn’t we expect a more even distribution of belief systems worldwide? Instead, geographical and cultural clustering of beliefs suggests that choice is less about free will and more about inherited norms and teachings. The underlying assumption of free will as a driver of religious belief deserves scrutiny: can individuals genuinely exercise free will in matters of faith if most are never exposed to the full spectrum of religious options?

The Hypothetical of an Equally Accessible Deity

Imagine a world where an omnipotent, omniscient God could reveal Himself directly to every child, transcending cultural and parental influences. In such a scenario, we might anticipate an even global distribution of belief, with individuals choosing or rejecting this deity based on personal convictions rather than inherited beliefs. However, the reality differs: children in predominantly Christian societies are overwhelmingly raised as Christians, those in Muslim societies as Muslims, and so forth.

Does this observed pattern imply that some individuals are inherently more resistant to God based on their birthplace or upbringing? Or, more troublingly, does it imply that God has not offered each individual an equal opportunity to know Him? Theological doctrines that attribute a fair and universal free will to humans must address the fact that one’s environment profoundly influences belief. Why would a just God create people with varying inclinations and access to belief in Him, based solely on geographic and cultural accident?

Consider a hypothetical child growing up in a conservative Muslim society. From an early age, she is taught that Allah is the one true God. Imagine, further, that she occasionally experiences doubt or anger, perhaps against oppressive social structures around her. In some doctrines, even a single unrepentant sin could lead to eternal condemnation. Would a just and compassionate deity truly condemn this individual eternally, simply because she was born into a culture that provided little exposure to alternative beliefs? This question underscores the issue: can a truly loving and fair God eternally punish individuals for their ignorance or lack of exposure to “correct” beliefs?

Free Will Versus Cultural Determinism

The notion that free will governs religious belief is difficult to sustain when examining belief patterns worldwide. If humans were given true, unbiased free will to select their faith, we might expect people to independently arrive at religious beliefs, regardless of social context. Yet, the overwhelming evidence shows that belief is profoundly affected by cultural and geographical factors.

In theology, it’s often argued that God endows each person with free will to choose between belief and unbelief. However, if the exercise of free will is so heavily influenced by external circumstances beyond one’s control, can it truly be considered “free”? This dilemma casts doubt on the fairness of any divine judgment based on religious adherence, suggesting instead that religious beliefs are as much a product of environment as they are of personal choice.

Scriptural Justifications and Implications

Some biblical passages attempt to address these concerns, suggesting that God, as the creator, possesses the sovereign right to shape and judge His creation however He chooses. For instance, Romans 9:20 states, “Shall what is formed say to the one who formed it, ‘Why did you make me like this?’” This passage implies a divinely sanctioned inequality in human inclinations toward faith. However, such reasoning raises significant questions. Does this conception of a deity align with attributes traditionally ascribed to God, such as compassion, justice, and mercy? Or does it instead reflect an attempt by humans to rationalize injustice and favoritism under the guise of divine mystery?

A Logical Examination of Belief Distribution

To evaluate the plausibility of divine fairness in belief distribution, we can formulate the following logical argument:

- Premise 1: If a just and omnipotent God exists, He would ensure that every individual has an equal and unbiased opportunity to know and choose Him.

- Premise 2: An omnipotent God would be capable of revealing Himself equally to all individuals, independent of their cultural or geographical context.

- Premise 3: If every individual has an equal opportunity to know God, the distribution of religious beliefs should be roughly equal worldwide, reflecting personal choice rather than cultural influence.

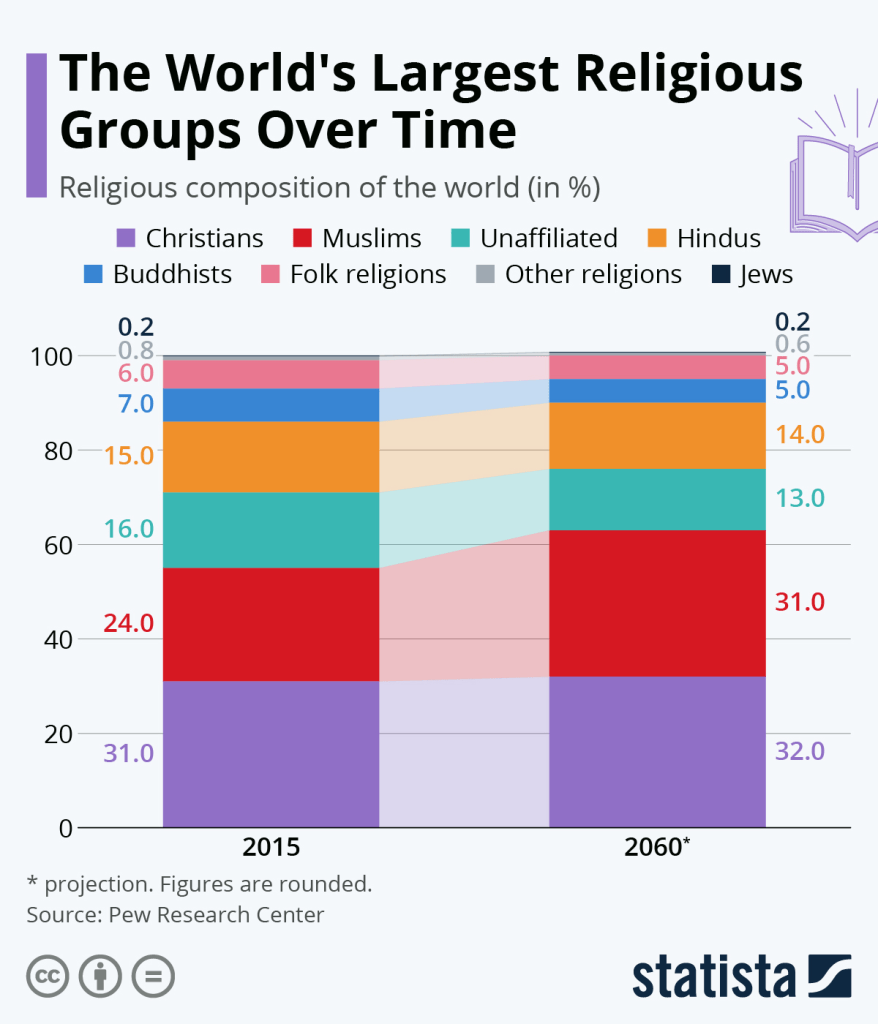

- Premise 4: Empirical observations indicate significant geographical and cultural clustering of religious beliefs.

Conclusion: The lack of an even distribution of belief suggests that religious affiliation is not determined by individual free will alone but is heavily influenced by uncontrollable external factors. Therefore, the premise that a universally just and omnipotent God would offer an equal chance of belief to all individuals appears contradicted by observable evidence.

Additional Considerations on Justice and Free Will

This argument invites further inquiry: if cultural and social environments dictate belief systems to such a degree, what does this say about divine justice? For believers in a just deity, the concept of equal access to salvation is central. If one’s eternal fate hinges on a choice to believe, yet that choice is heavily conditioned by circumstances beyond individual control, does this not create an unjust hierarchy of belief? Are some individuals arbitrarily favored over others, based on nothing more than the accident of birthplace?

Such discrepancies challenge the view of God as a universally fair judge. A truly equitable God would, presumably, provide every individual with a genuine and comparable opportunity to encounter and accept the truth, free from the overwhelming influence of cultural conditioning. The absence of such an even distribution suggests that belief is less about choice and more about social inheritance.

Implications and Reflections

These considerations lead us to question the logical implications of belief-based salvation models. If belief is not purely a matter of free will but is shaped by environmental and social factors, it becomes difficult to reconcile the notion of eternal punishment or reward based on belief alone. This raises a broader logical question: can a system of judgment truly be just if it does not account for the unequal distribution of belief?

By examining the geographical and cultural distribution of beliefs, we find that the concept of free will in choosing faith may be fundamentally flawed. Rather than reflecting an equal and voluntary choice, belief often appears to be a product of external influences beyond individual control. If a God does exist who is both just and omnipotent, the observed distribution of belief systems raises serious doubts about whether He has indeed provided all individuals with an equal chance to know and follow Him.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Cultural Conditioning and Free Will

- Premise 1: If religious belief were determined by free will, the global distribution of belief systems would be even, reflecting individual choice rather than cultural influence.

- Premise 2: The actual global distribution of religious beliefs is heavily clustered by geography and culture, with most people adopting the religion predominant in their immediate environment.

- Conclusion: Therefore, religious belief is influenced more by cultural conditioning than by true free will.

Argument 2: Divine Fairness in Revelation

- Premise 1: If a just and omnipotent God existed, He would ensure that all individuals, regardless of cultural or geographical background, have an equal opportunity to know and choose Him.

- Premise 2: An omnipotent God would be capable of revealing Himself directly to all individuals, independent of their cultural influences.

- Conclusion: The absence of such equal and universal revelation suggests that belief in God is not accessible equally to everyone, contradicting the notion of a universally fair deity.

Argument 3: Injustice of Belief-Based Judgment

- Premise 1: If eternal salvation or punishment is based on individual belief, then every individual must have equal access to knowledge of the “correct” belief.

- Premise 2: Given that cultural and geographical factors create unequal exposure to different religious beliefs, individuals do not have an equal chance to adopt the “correct” belief.

- Conclusion: Therefore, a system of eternal judgment based on belief alone is unjust, as it fails to account for the unequal distribution of religious exposure.

Argument 4: Logical Inconsistency in the Concept of Free Will

- Premise 1: If free will were genuinely the primary driver of religious belief, external influences such as family, culture, and geography would not significantly impact individual choice.

- Premise 2: In reality, these external factors strongly influence religious affiliation and are beyond individual control.

- Conclusion: Thus, religious belief is not purely a matter of free will, calling into question doctrines that rely on belief-based judgment as a fair measure of divine justice.

Argument 5: Implications for a Just Deity

- Premise 1: If a just God exists, He would not exhibit favoritism or preference for certain regions, ensuring a fair distribution of knowledge about Himself.

- Premise 2: Observations show significant geographical discrepancies in religious beliefs, indicating that belief is often inherited rather than chosen.

- Conclusion: The existence of these discrepancies suggests that either God does not provide equal access to belief or that belief distribution is not divinely guided, both of which challenge the idea of a just deity.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Examining Free Will and Religious Belief

CHRIS: I believe that everyone has free will to choose their faith, and God judges us fairly based on our beliefs. After all, we have the choice to accept or reject Him.

CLARUS: If free will truly dictated our beliefs, wouldn’t we expect a more even global distribution of religious faiths? Instead, most people adopt the religion predominant in their culture, not because they freely chose it, but because they inherited it.

CHRIS: But even if people are influenced by their culture, they still make their own choices about what to believe, right?

CLARUS: That assumption overlooks the impact of cultural conditioning. If religious belief were a free choice, shouldn’t we see people from all backgrounds choosing their beliefs independently of where or how they were raised? The fact that belief clusters geographically suggests that social and environmental factors limit individual choice.

CHRIS: I see what you’re saying, but God still gives everyone a chance to know Him. That’s fair, isn’t it?

CLARUS: That leads to another issue: if God is just and omnipotent, why doesn’t He make Himself equally accessible to everyone, regardless of where they’re born? A truly fair deity would ensure that each person, no matter their culture or background, has the same opportunity to know Him.

CHRIS: Perhaps God reveals Himself differently to each culture, and people still have the opportunity to find Him through their own traditions.

CLARUS: But if that’s the case, then God’s revelation isn’t universal. For example, a child raised in a devout Muslim family in Saudi Arabia might never be exposed to Christianity, while a child in the Bible Belt is unlikely to encounter Islam as a valid alternative. That disparity hardly seems like an equal opportunity to know God.

CHRIS: Well, maybe God judges people based on how they respond to the truths they have access to. Doesn’t that make it fair?

CLARUS: That brings up a problem with belief-based judgment. If eternal judgment is based on belief, but access to belief systems is so uneven, it raises questions about fairness. Can we really call a system just if some people have far fewer opportunities to make an informed choice?

CHRIS: But God might understand the heart and consider individual circumstances. He knows if someone would have chosen Him under different conditions.

CLARUS: That assumes a lot. Wouldn’t a just God ensure equal access to belief so that each individual could make an informed choice? This would avoid any need for speculating about hypothetical situations. The geographical clustering of belief suggests that choice is limited by external factors, not solely by free will.

CHRIS: I see your point, but we’re also taught that God has the right to shape our destinies as He sees fit. Scripture, like Romans 9:20, suggests that we shouldn’t question why He makes us the way we are.

CLARUS: True, but that raises conceptual concerns. A deity who creates individuals predisposed to certain beliefs and then judges them on that basis doesn’t align with the idea of a loving, just God. This rationale seems more like a human justification than a reflection of divine compassion.

CHRIS: So, are you saying that the distribution of belief systems we see in the world contradicts the concept of a just, omnipotent God?

CLARUS: Yes, exactly. If belief were purely a matter of free will and a just God existed, we’d expect a more balanced, universal opportunity to choose. Instead, the cultural inheritance of belief challenges the fairness of any system that judges based on it.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: Language and Cultural Conditioning

Consider how children adopt the language spoken in their households and communities. Just as a child raised in Japan will naturally learn Japanese without choosing it, individuals tend to adopt the religion of their environment. If free will were fully at play, we might see children spontaneously choosing different languages. Similarly, the cultural inheritance of belief shows that environment heavily influences religious faith, making it less of a choice and more of a conditioned response.

Analogy 2: National Loyalty and Influence

Imagine someone claiming that people freely choose which country to support in international competitions, such as the Olympics. In reality, most people root for their home country because of national identity and pride, not because they evaluated every country and made a choice. Just as national loyalty is strongly tied to birthplace, religious loyalty often aligns with one’s culture and upbringing, suggesting that environment shapes belief more than free will.

Analogy 3: Dietary Preferences and Cultural Exposure

Think about dietary preferences around the world—people from coastal regions often prefer seafood, while those in agricultural communities may favor grains or dairy. If dietary choices were entirely free, preferences would be more diverse, rather than reflecting local cultural habits and available foods. Similarly, religious beliefs reflect the cultural and geographical “menu” available to individuals, indicating that choice is limited by exposure rather than free will.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. Divine Justice Accounts for Circumstances

Theologians might argue that a just God considers each individual’s circumstances, including their cultural and environmental influences, when judging them. According to this view, God does not judge people merely on the basis of whether they profess the “correct” belief but rather on their moral integrity and how sincerely they respond to the truth available to them. This perspective allows for divine mercy in situations where belief was influenced by factors beyond individual control.

2. Universal Revelation Through Creation and Conscience

Another response could be that God has made Himself universally accessible through natural revelation, evident in creation and human conscience. Theologians might argue that, regardless of one’s cultural or religious background, everyone has access to an inherent understanding of God or the divine, accessible through the beauty and order of nature and an inner sense of right and wrong. This would imply that direct religious exposure is not strictly necessary for every individual to know of God’s existence and act accordingly.

3. Faith as a Response to Divine Grace, Not Cultural Inheritance

Some theologians propose that faith is not a product of cultural inheritance but a response to divine grace. In this view, God can reach people internally, beyond cultural barriers, through a personal relationship that transcends social influences. According to this belief, true faith arises from an individual’s openness to God’s grace, which operates beyond societal conditions, allowing people from any background to find and follow God if they are receptive.

4. Diversity of Religious Belief as Part of God’s Plan

Theologians might also argue that the diversity of religious beliefs is itself part of God’s plan, serving to provide different cultural expressions and paths that ultimately lead people toward Him. They could assert that God is working through a variety of traditions to guide people in a way suited to their cultural context, seeing religious diversity as a reflection of God’s creativity and desire for humans to seek Him through different avenues rather than through a singular religious path.

5. Free Will Requires a Spectrum of Choices

Another theological response might emphasize that true free will requires a variety of religious and secular choices, which naturally leads to diversity in belief systems. This view holds that a God who values free will allows people to explore various beliefs, even if some people are more likely to follow the faith of their culture. The presence of multiple belief systems could thus be seen as a test of faith, where individuals have the freedom to seek, question, and choose, ultimately allowing for a more genuine faith among those who come to believe.

Counter-Responses

1. Divine Justice Accounts for Circumstances

If divine justice accounts for individual circumstances, including cultural upbringing, this would imply that belief is not essential for salvation since God’s judgment could hinge on moral integrity rather than religious profession. However, this response contradicts traditional teachings that faith or belief in God is a prerequisite for salvation. Furthermore, if cultural influence mitigates accountability, then it logically follows that free will in religious belief is severely constrained, undermining any claim that people truly choose their faith independently of their background.

2. Universal Revelation Through Creation and Conscience

The idea that natural revelation provides universal access to knowledge of God fails to account for the wide variation in religious interpretations of creation and moral conscience. For example, natural phenomena have led to vastly different religious conclusions, from polytheism in ancient cultures to pantheism in some Eastern traditions. If nature and conscience alone suffice for belief, the resulting ambiguity undermines any argument for a clear, singular path to God. This response implies that divine revelation is fundamentally ambiguous and leads to contradictory beliefs, which seems inconsistent with a just and omnipotent deity who desires to be known universally.

3. Faith as a Response to Divine Grace, Not Cultural Inheritance

Claiming that faith arises from a personal response to divine grace independent of cultural influence overlooks the significant role of environmental conditioning in shaping one’s openness to religious ideas. Studies in psychology and sociology indicate that individuals are more likely to be receptive to beliefs that align with their cultural upbringing. If divine grace alone were sufficient to prompt belief, we would expect to see conversions independent of cultural contexts, yet religious affiliation still correlates strongly with geographical and cultural factors. This discrepancy raises questions about the efficacy of divine grace in reaching people equitably across different contexts.

4. Diversity of Religious Belief as Part of God’s Plan

The argument that religious diversity is part of God’s plan to guide people through culturally specific paths implies that contradictory religious doctrines are equally valid ways to know God. This perspective conflicts with the exclusivist teachings of many major religions, which claim to hold the ultimate truth. Furthermore, if contradictory beliefs all lead to the same God, this weakens the rationale for missionary work and religious exclusivity, which are often based on the idea that others need to know a specific truth. This response also fails to address why an omnipotent deity would allow doctrines to persist that could lead to eternal consequences for those who follow them mistakenly.

5. Free Will Requires a Spectrum of Choices

The claim that free will necessitates a diversity of choices overlooks the fact that some individuals are systematically disadvantaged in their access to certain beliefs due to geographic or cultural limitations. While choice is theoretically available, in practice, many people lack equal exposure to all religious options, rendering their choices limited. If free will requires equal opportunity to choose, then disparities in religious exposure undermine the validity of any divine judgment based on that choice, as individuals in certain contexts are denied the full spectrum of religious options. This response thus fails to justify the inequality in access to belief, which directly impacts religious autonomy.

Clarifications

Religion and the Natural Inclination Toward Irrational Faith

The global distribution of religious beliefs, characterized by strong cultural clustering and geographic patterns, suggests that human minds are, on the whole, not purely rational but naturally inclined toward irrational beliefs. This tendency is further reinforced by cultural dynamics that encourage conformity to community beliefs rather than individual rational inquiry. The fact that people largely adopt the religion of their environment rather than arriving at a religious belief through a purely rational process implies that faith is more a product of social conditioning and emotional influence than of critical thinking. By examining the geographic distribution of religions, we can logically conclude that human minds display a deficiency in rational thought, one that predisposes them toward unexamined beliefs and inherited faiths.

The Cultural Clustering of Religious Belief

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for the irrational basis of human faith is the geographic clustering of religions. If individuals were inclined to choose their beliefs through rational analysis, we would expect to see a relatively even global distribution of religions, with individuals freely choosing among belief systems based on careful evaluation. However, the reality is starkly different: people overwhelmingly adopt the religion predominant in their family and community, suggesting that belief is largely inherited rather than selected through an independent process. This clustering indicates that cultural factors heavily influence religious belief, often overriding individual critical thinking and rational inquiry.

The fact that children typically adopt the religion of their parents or community points to a natural inclination toward faith in what is familiar and comforting rather than what is critically examined. Human minds appear wired to accept beliefs that provide social cohesion and psychological security, even if these beliefs lack empirical evidence or logical coherence. This acceptance without scrutiny is symptomatic of a mind predisposed toward irrationality in matters of faith, as people prioritize belonging and social alignment over intellectual rigor.

Faith as an Emotional and Social Imperative

Religion is not just a set of beliefs but often a deeply embedded social identity that provides community, tradition, and a sense of purpose. Given that many religions offer comforting narratives about life after death, cosmic justice, and moral guidance, individuals are motivated to adopt and retain these beliefs because they provide emotional security and reduce existential anxiety. This emotional component of faith often overrides rational consideration, as human beings are generally more receptive to ideas that fulfill psychological needs than to ideas that challenge them with uncomfortable truths or complex reasoning.

Moreover, social imperatives strongly encourage conformity to local religious norms. People are often raised within a religious context that rewards belief and conformity while discouraging skepticism. In many societies, religious belief is woven into social structures, family dynamics, and personal identity, making it difficult to question without risking social alienation. This pressure to conform creates an environment where irrational beliefs are not only tolerated but reinforced, as faith is equated with loyalty and morality. Over time, this social reinforcement embeds irrational beliefs deeply within communities, normalizing them as unexamined truths.

Rational Deficiency and Cultural Influence

The human tendency to adopt faith-based beliefs that are culturally convenient rather than empirically grounded reveals a cognitive bias toward irrationality. The very concept of faith, by definition, implies a belief without evidence—a cognitive leap that contradicts rationality. Yet, rather than questioning this instinct, most people embrace faith unquestioningly, displaying a deficiency in rational thought that may be inherent to the human mind. Rationality requires a willingness to scrutinize beliefs, yet this willingness is notably absent in most religious contexts. Instead, cultural dynamics encourage an acceptance of inherited beliefs and discourage doubt, positioning faith as a virtue and skepticism as a threat to communal harmony.

This deficiency in rational thought is further demonstrated by the resilience of religious beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence or logical inconsistency. People are generally unwilling to abandon their faith even when faced with rational arguments that challenge its premises. This resistance highlights the human mind’s propensity to cling to irrational beliefs that have been socially and culturally ingrained, a trait that suggests natural inclination toward faith over reason.

Conclusion: The Human Mind’s Bias Toward Irrational Faith

In analyzing the geographic and cultural distribution of religions, it becomes evident that human beings have a strong natural bias toward irrational faith. This inclination is reinforced by social and cultural dynamics that reward conformity and discourage critical examination of beliefs. If the human mind were truly rational, we would expect religious beliefs to vary based on logical scrutiny and empirical evidence. Instead, we see that faith is largely a product of social inheritance and emotional need, reflecting a cognitive tendency to accept comforting narratives without question.

The persistence of faith across generations and regions suggests that human rationality is not the primary driver of religious belief. Instead, faith functions as an emotional and social mechanism, one that has developed to provide psychological comfort and group cohesion rather than to reflect an objective understanding of reality. The prevalence of religious belief in forms that defy reason implies that the human mind is predisposed to accept irrational beliefs, a predisposition that is perpetuated by cultural influences that elevate faith as a virtue. This widespread inclination reveals a fundamental deficiency in rational thought, a limitation that prevents many individuals from engaging in the critical analysis necessary to transcend inherited, irrational faiths.

The Logical Exclusivity of a True God: Arguments Against Religious Plurality

The following syllogistic arguments explore the logical implications of religious exclusivity when considering the existence of a true God. If a true God exists, it would logically follow that this deity possesses a consistent, universal nature, allowing only one correct religious interpretation. Since most religions offer mutually contradictory descriptions of God, it implies that only one can be correct—or, quite possibly, that none accurately represent this deity. These arguments suggest that the contradictory nature of religious claims and the lack of a universally compelling, verifiable view of God point toward the conclusion that most, if not all, religions are likely false in their portrayal of a true God.

Syllogism 1: Exclusivity of a True God

Premise 1: If a true God exists, then this God would have a consistent and universal nature that is exclusive to itself.

Premise 2: Different religions describe contradictory characteristics and teachings about God (e.g., monotheism vs. polytheism, immanence vs. transcendence).

Conclusion: Therefore, if a true God exists, only one religious view of this God could be correct, making the concept of God mutually exclusive among religions.

Symbolic Logic:

(If a true God exists, then all true descriptionsof God

must reflect an exclusive nature

of

.)

(The exclusive characteristics attributed to God in religions 1 throughcontradict each other.)

(If a true God exists, then there exists a unique, true religious view of this God.)

Syllogism 2: Mutual Exclusivity Implies Falsehood in Most Religions

Premise 1: If only one religious view of God is correct, then all contradictory religious views must be false.

Premise 2: Most religions contain incompatible descriptions of God and therefore cannot all be correct.

Conclusion: Therefore, most religions are false with respect to their claims about the true God.

Symbolic Logic:

(If there exists one unique true religious view, then any religious view

that contradicts

must be false.)

(Religions 1 throughcontradict one another.)

(Thus, all religions that are not the one true religion are false.)

Syllogism 3: Plausibility of All Religions Being False

Premise 1: For a God to be mutually exclusive, one true description of this God must exist.

Premise 2: No religion provides a universally compelling and verifiable description of God that meets the exclusivity criterion.

Conclusion: Therefore, it is plausible that all current religions are false with respect to describing the true God.

Symbolic Logic:

(If a true God exists, there exists a unique true religious view.)

(No religion provides a universally compelling and consistent description.)

(Thus, if a true God exists, it is possible that all current religions are false.)

Final Argument Summary

Based on these syllogisms, the argument concludes that:

- A true God would be mutually exclusive, allowing only one true description.

- Most religions describe contradictory versions of God and cannot all be true, implying that most, if not all, are false.

- Given the lack of universally compelling evidence for any single religious view, it is plausible that all current religions are false with respect to accurately describing the true God.

In symbolic form:

This structure concludes that a truly exclusive God concept undermines the validity of most religions and, given the contradictions and lack of universal credibility, suggests the potential falsehood of all current religions.

Psychological Mechanisms Underlying Religious Superiority and Condemnation

Religious belief, particularly within tightly knit communities, can foster a potent sense of superiority that fuels condemnation of those outside the faith. This tendency is driven by psychological mechanisms such as in-group bias, social identity, cognitive dissonance, and confirmation bias—all of which reinforce the perception that one’s beliefs are uniquely true and morally superior. In many cases, these psychological forces do not merely promote pride but can lead individuals to view other religions or belief systems as fundamentally flawed, even to the point of believing that followers of other faiths deserve eternal punishment.

In-group bias plays a crucial role in the dynamics of religious condemnation. This bias causes people to favor their own group and, by extension, perceive outsiders as inferior or even sinful. Within religious communities, in-group bias often translates into the belief that one’s own faith is the only true path to salvation. For instance, a Christian community may view those who do not accept Jesus as condemned to eternal Hell, not just out of doctrinal teachings but because this exclusion reinforces a powerful psychological distinction between “us” and “them.” This separation creates a psychological barrier that dehumanizes outsiders and rationalizes their fate as deserved, even if that fate is framed in terms of everlasting suffering.

Social identity theory further amplifies this phenomenon. People derive significant aspects of their self-worth from group affiliations, including religious beliefs. For some believers, their identity as members of the “true faith” becomes central to their understanding of themselves and their world. This identification not only enhances pride in their religious identity but also fosters an inclination to see other belief systems as false or even dangerous. In extreme cases, this can escalate to a sense of divine superiority that justifies the idea of eternal punishment for those who reject the “truth.” When one’s self-image is tied to the idea of belonging to the chosen group, it becomes psychologically reinforcing to believe that outsiders who reject this group are deserving of punishment, as it validates the perceived importance and exclusivity of one’s own beliefs.

Cognitive dissonance exacerbates this inclination by making it difficult for believers to empathize with or understand alternative perspectives. When confronted with the beliefs of other religions or secular worldviews, believers may experience dissonance, particularly if these beliefs challenge the validity of their own. Rather than engaging with these differing perspectives, many individuals resolve the dissonance by reaffirming their own beliefs, sometimes in extreme ways. This can lead to an entrenched view that those outside the faith are willfully rejecting the truth and, consequently, deserve condemnation. In effect, cognitive dissonance helps reinforce an uncompromising stance that frames non-believers as not only misguided but morally culpable for their lack of belief.

Confirmation bias also plays a critical role by selectively reinforcing information that supports the belief in one’s religious superiority and the idea that outsiders deserve punishment. Religious communities often emphasize teachings or scriptural interpretations that highlight their exclusivity, framing salvation as available only to those who follow their particular path. This bias leads believers to focus on aspects of doctrine that support eternal damnation for outsiders, while downplaying any teachings that may encourage understanding or compassion. Over time, this selective focus builds a narrative where only members of the faith are worthy, while those who do not accept the “truth” are considered deserving of Hell.

Collectively, these psychological mechanisms create an insular worldview that not only reinforces pride but fosters a belief that others are rightly condemned for rejecting what is considered the one true faith. When reinforced by strong group dynamics and selective interpretation of religious doctrine, these tendencies can create a dangerous mindset where believers see others not just as different but as morally and spiritually inferior, even worthy of eternal punishment. Recognizing the role of in-group bias, social identity, cognitive dissonance, and confirmation bias is essential to understanding how religious beliefs can cross the line from communal pride to active condemnation of others. Addressing these tendencies requires a conscious effort to promote critical self-reflection, encourage empathy, and cultivate openness to diverse beliefs, challenging the notion that those outside one’s own faith are inherently deserving of punishment.

Moving from Common Religious Elements to Localized Notions

The Biological Roots and Cultural Branches of Religion

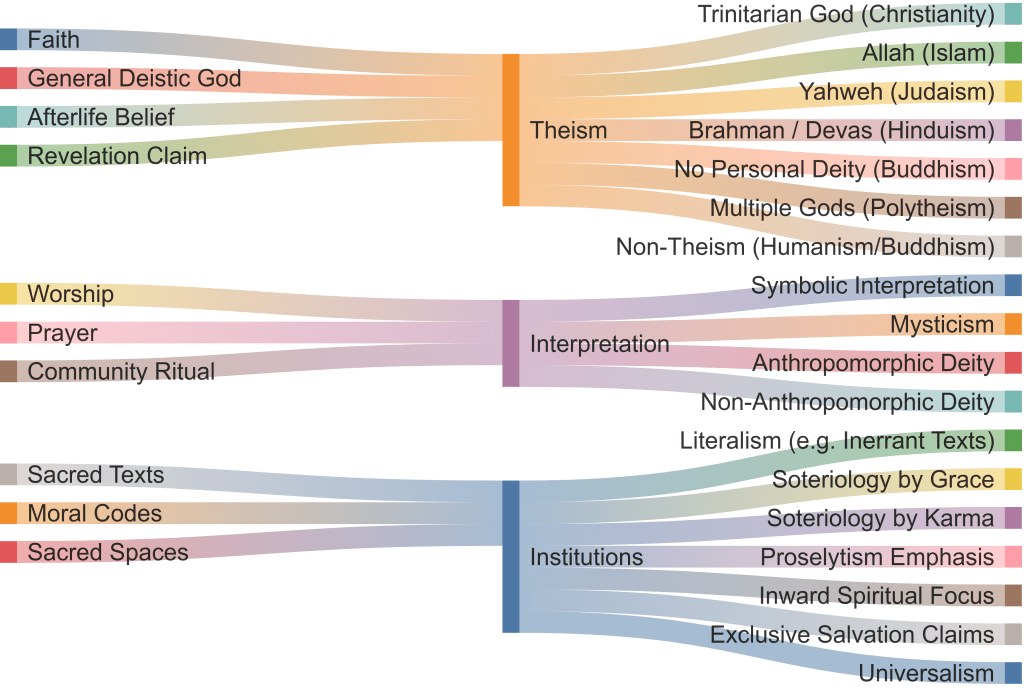

Religions across the globe, despite their enormous doctrinal diversity, share a striking set of core elements—faith, worship, prayer, sacred texts, moral codes, and beliefs in divine agents or an afterlife. The Mermaid Sankey diagram (attached) visually demonstrates how these shared elements flow into more specific religious theologies, interpretive styles, and institutional practices. While the chart is taxonomic, its deeper significance lies in what it reveals about the human condition: namely, that the commonalities in religion are not coincidental, but emerge from shared emotional substrates and genetic dispositions, while the divergences arise from cultural, historical, and ecological adaptations.

Shared Emotional Architecture: Faith, Ritual, and the Deistic Impulse

At the broadest level of the diagram, we find Faith, General Deistic God, Afterlife Belief, and Revelation Claim. These elements reflect evolutionarily conserved emotions—not metaphysical insights. The longing for order, the fear of death, the desire for cosmic justice, and the need for social cohesion are all intrinsic to the human nervous system. These emotions were naturally selected because they enhanced group survival, especially in prehistoric environments where coordinated behavior, trust, and purpose could mean the difference between extinction and endurance.

Faith, then, can be seen not as evidence for the divine, but as a neurological affordance—a cognitive shortcut that allows for confidence in uncertain environments. The general concept of a god or gods taps into agency detection mechanisms in the brain, which evolved to keep early humans safe from predators and social threats. Better to attribute rustling in the bushes to an agent (even a fictive one) than to ignore it and die. Over time, this gave rise to the deistic template seen across cultures.

Core Practices: Ritual and the Need for Communal Synchrony

Religious practices such as worship, prayer, and community ritual reflect a social-emotional need for synchrony. These behaviors promote emotional bonding, reduce interpersonal conflict, and elevate group morale. Neuroscience research supports this: synchronized chanting, singing, and movement release oxytocin and endorphins, increasing trust and perceived closeness among participants.

This explains the near-universal inclusion of group rituals in religions regardless of geography. Though the doctrinal content of these practices diverges (as shown in the “Interpretation” branch of the diagram), the underlying emotional regulation function remains constant. In this way, ritual serves as a neural technology to stabilize communal emotions, reducing uncertainty and reinforcing group identity.

Core Structures: Moral Codes and Textual Authority

The lower branch of the diagram captures Sacred Texts, Moral Codes, and Sacred Spaces—the infrastructure of religion. These components serve as externalized memory systems, reinforcing shared norms and anchoring group cohesion in larger societies. As social groups expanded beyond Dunbar’s number (~150 individuals), reputational enforcement and verbal memory became insufficient. Codified moralities and sacred geographies emerged to bind anonymous members to the same behavioral standard.

Again, the human brain is implicated. Moral disgust, empathy, and fairness have neural correlates, but the codification and sacralization of these intuitions into enduring laws—like the Ten Commandments or Buddhist precepts—occurred culturally. They were not genetically coded but built on a shared affective base.

From Common Substrate to Cultural Specificity

The right side of the Sankey diagram illustrates divergence. This is where culture takes the reins from biology. We see the emergence of Trinitarianism, Karma, Literalism, and Universalism—concepts that are not rooted in common biology but in localized social narratives, historical contingencies, and theological evolution.

For instance:

- Christianity’s Trinitarian model is a historical-theological artifact shaped by early church councils and Roman cultural pressures—not by emotional universals.

- Hinduism’s polytheism and karma system reflect India’s pluralistic oral tradition and cyclical cosmology, influenced by its agrarian rhythms and caste system.

- Buddhism’s non-theism emerged as a counter-response to Vedic ritualism and the perceived futility of eternal gods.

- Islam’s emphasis on literal revelation responds to the geopolitical context of 7th-century Arabia, where oral precision was paramount in unifying diverse tribes.

These distinctions illustrate that once emotional needs are scaffolded by religion, they become malleable. Culture bends biology, shaping the doctrinal and structural features of religion to suit geography, politics, and historical memory.

Conclusion: The Universal Scaffold, the Cultural Skin

Religion is not merely a set of beliefs; it is a biocultural artifact. The common elements—faith, ritual, sacred stories—are anchored in universal human affect, shaped by shared neurology and evolutionary pressures. The divergences—doctrine, dogma, eschatology—are the cultural skin stretched over this biological scaffold, colored by history and context.

The diagram provided elegantly captures this dual structure: what we share because of our species and how we differ because of our stories.

Leave a comment