Consider the Following:

Summary: This article argues that a truly loving and just God would not condemn individuals to eternal damnation for rationally exploring conflicting religious claims and arriving at uncertainty, as this would contradict the values of intellectual integrity and sincere truth-seeking. It highlights the role of cultural influences, subjective spiritual experiences, and the necessity of rational evidence in forming beliefs, concluding that such condemnation would be inconsistent with the nature of a compassionate deity.

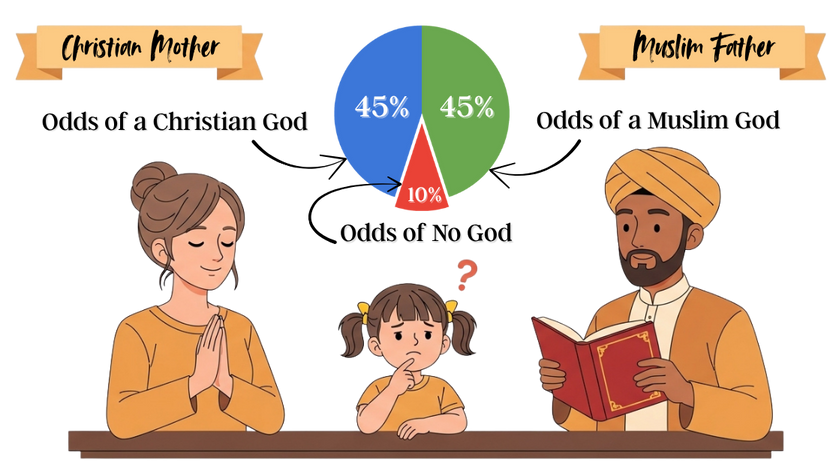

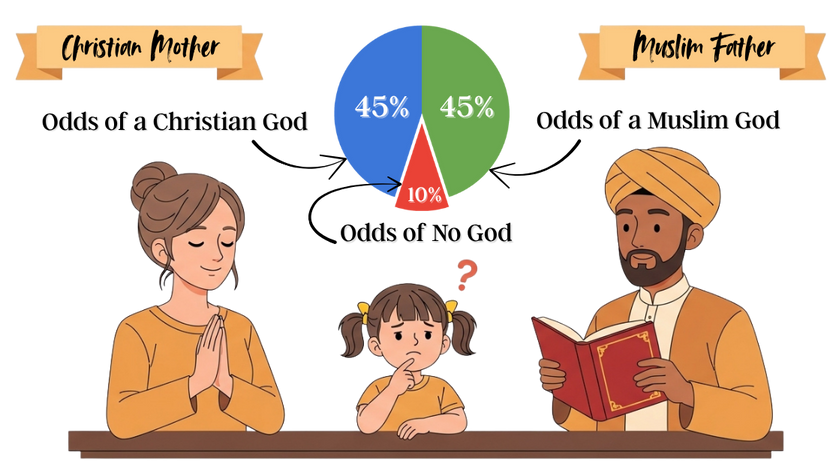

Imagine a thoughtful, inquisitive individual named Mariam. Born to a Christian mother and a Muslim father, she grows up immersed in both religions, each parent genuinely convinced that if Mariam’s heart is open, their God will make Himself known. As she matures, Mariam seeks spiritual truth with an open mind, reading both the Bible and the Quran, attending church services and mosque gatherings, and experiencing profound spiritual feelings in both contexts.

Yet, Mariam finds herself equally persuaded by each worldview, torn between two conflicting yet rational belief systems. She holds, with sincerity, about a 45% conviction in both Allah and Jehovah, while leaving a 10% margin for the possibility that neither exists. Is her journey of rational exploration, guided by a genuine desire to understand and embrace truth, worthy of condemnation and perhaps an eternal agonizing destiny?

Would a truly loving God demand absolute certainty in one belief while eternally punishing those who, despite their best efforts, remain uncertain?

The Ethical Expectation of Rationality

Mariam’s dilemma highlights a fundamental question: Is it just for a deity to demand absolute belief in the face of ambiguous or conflicting evidence? Rationality requires that individuals form beliefs based on the weight of available evidence and that they hold those beliefs only as firmly as the evidence allows. If Mariam is expected to ignore reason and arbitrarily pick one path to avoid damnation, this raises profound ethical concerns.

An authentic God would likely value rational integrity, not arbitrary allegiance. The expectation that Mariam should adopt belief without adequate evidence seems to promote a form of irrationality that undermines intellectual honesty. Wouldn’t a truly loving God appreciate the courage of a person like Mariam to follow reason, even if it means grappling with doubt?

The Problem of Conflicting Divine Claims

Religions across the world present competing claims about the nature of God, salvation, and truth, each with its own historical, cultural, and spiritual frameworks. Suppose God is loving, just, and all-knowing. In that case, it follows that He would understand the difficulty faced by people like Mariam, born into a world where religious diversity is inevitable and where access to any single truth is contingent upon numerous factors outside an individual’s control.

- Consider the cultural lottery—a person’s place of birth heavily influences religious beliefs. Someone born into a devout Hindu family in India is likely to adopt Hinduism, just as someone born into a Christian family in Texas may be inclined towards Christianity. If God created a world with such diversity, wouldn’t He recognize that belief is often shaped by circumstances, not an individual’s rebellion or malice? Wouldn’t He ensure his existence was unequivocal to all in all cultures?

- If God values truth-seeking, wouldn’t He encourage inquiry, doubt, and careful consideration of evidence? A system that punishes people for rationally considering multiple options or doubting unproven claims seems antithetical to the value of intellectual honesty. Would a just God truly punish someone for failing to adhere to a belief simply due to the limited evidence or cultural influence?

Distinguishing Between Divine and Deceptive Experiences

Many religious adherents argue that their spiritual experiences provide confirmation of their beliefs. However, the subjective nature of spiritual experiences means they can be interpreted differently by followers of various religions. What one person perceives as the presence of Jehovah, another might interpret as Allah’s guidance. Each interpretation, while sincere, is influenced by personal and cultural backgrounds, and there is no empirical way to confirm the absolute truth of one over the other.

Is it just, then, for God to condemn individuals based on their interpretation of an experience that could reasonably be attributed to different deities?

The ability to discern divine truth from deception would require a clear, universal standard accessible to all individuals. If such clarity were provided by a truly just deity, why do believers across religions have such varied interpretations of their spiritual encounters? Expecting people to discern which deity is correct under these conditions seems unfair and inconsistent with the notion of a loving God.

The Role of Doubt and Intellectual Integrity

Throughout history, doubt has played a crucial role in the search for truth, whether in science, philosophy, or theology. Figures like Thomas Aquinas and even Martin Luther grappled with profound questions about faith, doubt, and rationality. Would a God who values truth expect individuals to suppress their doubts and follow beliefs without questioning?

If faith is a journey toward understanding, wouldn’t a loving God welcome sincere seekers—even those who doubt or question—as long as their hearts are genuinely open to truth? A condemnation of rational doubt and inquiry appears contrary to the ideals of a benevolent deity.

- Valuing intellectual integrity: If Mariam and others like her remain unconvinced by the arguments for a single deity despite extensive exploration, would a loving God value their honesty or punish their doubt?

- Encouraging open-mindedness: If God created humans with reasoning abilities, wouldn’t He expect them to use these faculties responsibly? A requirement for blind belief rather than reasoned conviction would seemingly devalue the intellectual gifts bestowed upon humanity.

Conclusion: The Nature of a Just and Loving Deity

Based on these considerations, the following logical conclusions arise:

P1: A truly loving God would not eternally condemn individuals for rational disbelief or uncertainty.

P2: The traditional depiction of the Christian God includes the condemnation of those who rationally disbelieve in Him.

Conclusion: Therefore, by this standard, the traditional depiction of the Christian God appears inconsistent with the concept of a loving and just deity.

Wouldn’t a truly loving God be characterized by mercy, understanding, and the appreciation of sincere truth-seeking, regardless of the specific conclusions reached?

Ultimately, if God values the pursuit of truth and the use of reason, then He would not be an authoritarian figure demanding blind allegiance but a compassionate being who appreciates the struggles, doubts, and intellectual integrity of His creations.

A Companion Technical Paper:

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Incoherence of Eternal Punishment

- Premise 1: A loving and just entity would uphold the principle of proportionality, ensuring consequences are fair and finite in relation to the actions committed.

- Premise 2: The concept of eternal punishment for finite actions, as depicted in traditional Christianity, violates the principle of proportionality.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the traditional depiction of the Christian God appears inconsistent with the notion of a loving and just entity.

Argument 2: Unfair Condemnation Based on Cultural and Environmental Factors

- Premise 1: A loving and just entity would account for cultural and environmental influences that shape individuals’ beliefs beyond their control.

- Premise 2: The traditional Christian God is said to condemn individuals for failing to believe in specific tenets, despite these beliefs often being influenced by cultural upbringing and sincere reasoning.

- Conclusion: Thus, the traditional depiction of the Christian God is inconsistent with the notion of a loving and just entity.

Argument 3: Demand for Rational Coherence

- Premise 1: Rational beings require coherence and internal consistency in the entities they are expected to accept as real or authoritative.

- Premise 2: The traditional Christian God, as depicted, contains contradictions between claims of love and justice and doctrines of eternal punishment and belief-based condemnation.

- Conclusion: Therefore, rational beings cannot reasonably accept the traditional depiction of the Christian God without clear reconciliation of these contradictions.

Argument 4: Rejection of Incoherent Claims

- Premise 1: Rational beings reject concepts or entities that fail to provide coherent explanations for contradictions.

- Premise 2: The traditional Christian God fails to provide coherent explanations for the apparent inconsistencies between claimed love and justice and the doctrines of eternal damnation and culturally-influenced belief systems.

- Conclusion: Therefore, rational beings should dismiss the traditional depiction of the Christian God as incoherent.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

The Inconsistencies of the Traditional Christian God

CHRIS: The Christian God is loving and just. He desires for all people to know Him and offers salvation to those who believe in Him.

CLARUS: If the Christian God is truly loving and just, then how do you explain the concept of eternal punishment for finite actions? Proportionality is a core aspect of any rational justice system, and eternal damnation for a lifetime of mistakes seems entirely disproportionate.

CHRIS: God’s justice is perfect and beyond human understanding. He punishes sin because it is an offense against His infinite holiness.

CLARUS: That response doesn’t address the issue of proportionality. A loving and just entity would ensure that the consequences align fairly with the actions. Even if you invoke God’s infinite holiness, how can an infinite punishment be justified for actions limited to a finite human lifespan?

CHRIS: But God doesn’t send people to hell arbitrarily. People choose separation from Him by rejecting His offer of salvation.

CLARUS: That argument presupposes that everyone has equal access to the information needed to make this choice. Consider individuals raised in non-Christian cultures. Their beliefs are shaped by cultural and environmental factors beyond their control. Would a loving and just God condemn someone for sincerely following the belief system they were exposed to, especially if they had no rational reason to favor Christianity?

CHRIS: God reveals Himself to all people through creation, conscience, and the Gospel message. Everyone has the opportunity to seek Him.

CLARUS: That’s a sweeping claim that ignores the complexity of human experiences. A person raised in a deeply devout Hindu family, for instance, would naturally interpret their conscience and experiences through a Hindu framework. It’s unreasonable to expect such a person to interpret their reality in a way that aligns with Christianity. Wouldn’t a just God account for these differences rather than punishing people for being born in specific cultural circumstances?

CHRIS: Faith plays a role here. God expects people to seek Him with an open heart and trust in His revelation.

CLARUS: Trusting without evidence contradicts rational principles. If God is truly the epitome of reason and justice, wouldn’t He encourage rational inquiry rather than blind trust? For instance, you claim God is both loving and just, but the doctrines of eternal damnation and belief-based salvation introduce glaring contradictions. How can a rational mind accept a deity with unresolved inconsistencies?

CHRIS: Perhaps it’s a matter of faith transcending human reason. God’s ways are higher than our ways.

CLARUS: That explanation demands the forfeiture of rationality. As rational beings, we are compelled to dismiss claims or entities that fail to reconcile internal contradictions. If the traditional depiction of the Christian God can’t provide coherent answers, it becomes indistinguishable from an incoherent construct. Until such contradictions are resolved, there’s no rational basis to accept this God as real or worthy of consideration.

CHRIS: But dismissing God entirely might close the door to eventual understanding or salvation.

CLARUS: Dismissing incoherent claims isn’t closing the door—it’s upholding the commitment to reason. If there’s no explanation for these contradictions from God or His alleged messengers, the rational course is to reject the claim. Rational inquiry, not biblical faith, is the path to truth.

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Unfair Teacher

Imagine a teacher who gives students a test but provides only half the class with the study material while the other half receives no guidance. At the end of the test, the teacher fails everyone who didn’t get a perfect score, regardless of the resources they had. Would such a teacher be considered fair or just? The teacher’s actions parallel the idea of a God who condemns individuals born into different cultural and religious environments, expecting them to believe in Christianity despite not having access to its teachings or being shaped by other belief systems.

Analogy 2: The Unjust Judge

Picture a judge sentencing a person to life imprisonment for a minor infraction, such as jaywalking. The punishment is completely out of proportion to the act, making the judge seem irrational and cruel. Would such a judge reflect any sense of justice? This scenario mirrors the concept of eternal punishment for finite human actions, which contradicts the principle of proportionality that any rational system of justice would uphold.

Analogy 3: The Biased Game Show Host

Consider a game show where the host claims everyone has an equal chance to win, but the rules are explained only in one language. Contestants who don’t speak that language are expected to guess the rules or face disqualification. Would such a competition be genuinely fair? This is analogous to a God who expects belief without ensuring universal and clear access to the required information, disproportionately favoring those born into environments conducive to Christianity.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. God’s Ways Are Beyond Human Understanding

Theologians may argue that human logic and justice are limited and cannot fully comprehend the infinite holiness and justice of God. They may claim that eternal punishment for sin is consistent with God’s nature, even if it seems disproportionate to human reasoning. From this perspective, the apparent contradictions are not flaws but evidence of a higher divine logic that transcends human understanding.

2. Eternal Punishment Reflects the Gravity of Sin

Some theologians contend that sin, being an offense against an infinitely holy God, requires an infinite consequence. They argue that the punishment matches the magnitude of the offense, not in temporal terms but in the nature of the relationship violated. Thus, eternal damnation is seen as proportionate to the weight of sin when viewed through the lens of divine perfection.

3. God’s Justice Includes Mercy

Theologians might respond that while God is just, He is also merciful, offering salvation through grace and the sacrifice of Jesus. They argue that eternal punishment is avoidable through belief and repentance, making it a choice individuals make rather than an imposed injustice. From this view, God’s justice provides the framework, but His mercy offers the solution.

4. God Reveals Himself Universally

The claim that belief is contingent on cultural and environmental factors may be countered with the argument that God reveals Himself universally through creation, conscience, and spiritual experiences. Theologians might argue that no one is truly without access to the knowledge of God, making disbelief a deliberate rejection of this universal revelation.

5. Faith Requires Trust Beyond Evidence

Theologians may assert that faith is not about blind belief but about trusting in God’s character and promises, even when evidence is limited or unclear. They may argue that faith itself is a virtue that strengthens the relationship between God and humanity, and that rational inquiry alone cannot lead to spiritual truth.

6. Cultural Differences Are Addressed by Divine Justice

In response to the concern about cultural influences, theologians might argue that God judges individuals based on the knowledge they have and the sincerity of their search for truth. They may claim that divine justice takes into account one’s circumstances and that salvation is not strictly limited to explicit Christian belief in cases where it is inaccessible.

7. God’s Love Includes Accountability

Some theologians argue that true love requires holding individuals accountable for their actions. They may claim that eternal separation from God is the natural consequence of rejecting Him, not an arbitrary punishment. From this perspective, God’s love is consistent with His justice, as it respects human freedom and responsibility.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “God’s Ways Are Beyond Human Understanding”

Invoking the idea that God’s ways are beyond human understanding undermines any meaningful discussion about God’s nature. If human logic cannot apply to God, then the claims of God being loving or just are equally meaningless because these terms rely on human concepts of love and justice. Appeals to mystery fail as an explanation if they also render God’s qualities unintelligible, leaving no coherent standard by which to assess divine actions.

2. Response to “Eternal Punishment Reflects the Gravity of Sin”

Claiming that sin requires infinite punishment due to God’s infinite holiness is arbitrary and lacks proportionality. A finite being, with finite understanding, cannot rationally be held accountable for offending an infinite standard they cannot fully comprehend. Justice requires proportionate consequences, and equating finite transgressions to infinite punishment contradicts any rational system of accountability.

3. Response to “God’s Justice Includes Mercy”

The offer of salvation through grace does not address the underlying issue of eternal punishment’s disproportionate nature. If salvation is presented as a way to avoid an unjust penalty, it raises questions about why such a penalty exists in the first place. True mercy would eliminate the need for an eternal punishment system altogether, especially for sincere truth-seekers who fail to arrive at the Christian faith through no fault of their own.

4. Response to “God Reveals Himself Universally”

The claim that God reveals Himself universally assumes that all people can interpret creation or conscience in a way that leads them to the Christian God, which is demonstrably false. Cultural and environmental factors heavily influence belief systems, and there is no clear evidence that these revelations provide equal access to all. If God’s revelation were truly universal, religious diversity would not be so profound and persistent.

5. Response to “Faith Requires Trust Beyond Evidence”

Expecting faith to operate without sufficient evidence undermines rational inquiry. Trust without evidence is not a virtue, especially when the stakes involve eternal consequences. A deity worthy of acceptance would encourage rational evaluation and provide clear evidence for belief, rather than demanding blind trust in the absence of verifiable claims.

6. Response to “Cultural Differences Are Addressed by Divine Justice”

Theological claims that God judges individuals based on their circumstances contradict doctrines that salvation is exclusively through Christ. If divine justice truly accounts for cultural and environmental influences, the exclusivity of Christian salvation becomes incoherent. Reconciling cultural fairness with exclusivity would require a clearer explanation than those traditionally offered.

7. Response to “God’s Love Includes Accountability”

Equating accountability with eternal separation from God conflates justice with retribution. True accountability would involve opportunities for correction and growth, not infinite punishment. Love cannot coexist with eternal damnation, as this represents abandonment rather than meaningful accountability, making the claim inconsistent with any coherent notion of love.

Clarifications

Mariam’s Rational Epistemic Position

Mariam, caught between the competing beliefs of her Christian mother and Muslim father, represents the archetype of a rational inquirer navigating conflicting worldviews. As she evaluates the evidence available to her, she concludes with sincerity and intellectual honesty that Christianity and Islam each hold a 45% probability of being true, while there is a 10% probability that there is no God. This position, grounded in her evaluation of evidence, should not be swayed by emotional or social pressures, even those exerted by her well-meaning parents. Mariam’s unwavering commitment to reason and probabilistic thinking exemplifies the integrity required for any seeker of truth.

Probabilistic Belief as the Rational Standard

Mariam’s approach is rooted in the principle that beliefs should align with the weight of available evidence. Epistemic honesty demands that one proportion their belief to the strength of the evidence, no more and no less. By assigning probabilities of 45%, 45%, and 10%, Mariam reflects her best attempt to synthesize the arguments, experiences, and cultural influences she has encountered. To abandon this probabilistic stance in favor of absolute certainty would require her to ignore evidence or overestimate its reliability, both of which are antithetical to rational inquiry.

Her epistemic position also underscores the importance of remaining open to revision. Should new evidence or arguments arise, Mariam is prepared to adjust her probabilities accordingly. This adaptability is essential to the pursuit of truth, as it ensures beliefs remain flexible in light of evolving information.

The Problem of Parental Pressure

Mariam’s parents, each firmly committed to their respective faiths, apply pressure for her to adopt one belief fully. While this pressure is likely born from love and concern, it introduces a conflict that challenges her epistemic autonomy. To abandon her rational stance in favor of appeasing one parent would not only betray her integrity but also establish a dangerous precedent: the substitution of social or emotional conformity for evidence-based reasoning.

Furthermore, any attempt to force Mariam into absolute belief would disregard the complexity of her intellectual journey. Rational inquiry requires the courage to withstand external pressures and maintain a position that aligns with one’s honest assessment of evidence, even when that position is unpopular or misunderstood.

The Value of Intellectual Integrity

Mariam’s epistemic position reflects not indecision but a deep respect for the complexity of the question she faces. Assigning equal probabilities to Christianity and Islam does not mean she is apathetic or unwilling to commit; rather, it demonstrates that she values intellectual integrity over premature resolution. The 10% probability she assigns to the absence of God further highlights her willingness to entertain multiple possibilities, acknowledging the limits of her knowledge without succumbing to unwarranted certainty.

Her position also serves as a model for others navigating religious or philosophical dilemmas. By refusing to claim more certainty than the evidence allows, Mariam demonstrates the courage to embrace uncertainty as a necessary part of honest inquiry. This courage ensures that her belief system remains rational and grounded, rather than dictated by external pressures or unfounded assumptions.

The Broader Implications of Mariam’s Approach

Mariam’s situation illustrates a universal truth about belief formation: evidence, not authority or tradition, must guide our conclusions. In a world of diverse worldviews and competing truth claims, the ability to hold nuanced, probabilistic positions is essential. By maintaining her epistemic stance, Mariam challenges the expectation that belief must be binary or absolute. Instead, she embodies a more rational and open approach that fosters dialogue and mutual understanding.

Her probabilistic position also underscores the importance of epistemic humility. Rather than asserting absolute knowledge, she acknowledges the limits of her understanding and the complexity of the evidence before her. This humility strengthens her intellectual integrity, allowing her to engage with others’ perspectives without dogmatism or defensiveness.

Conclusion: Standing Firm in Rational Probabilistic Belief

Mariam’s 45-45-10 probabilistic position is not a mark of weakness or indecision but a testament to her rationality, intellectual honesty, and epistemic humility. By aligning her beliefs with the evidence at hand, she resists the pressure to conform to her parents’ expectations and remains true to her commitment to reason. Mariam’s stance reminds us that the pursuit of truth is often marked by uncertainty, and that courage lies not in clinging to unwarranted certainties but in embracing evidence-based probabilities with unwavering integrity.

The Incoherence of the Traditional Depiction of the Christian God with a Loving and Just Deity

Throughout history, countless individuals have grappled with the notion of a God who is simultaneously loving, just, and capable of condemning rational individuals to eternal punishment. If such a being exists, it is reasonable to expect that this God would embody both compassion and fairness in a way that resonates with the highest principles of justice and love. However, many aspects of the traditional Christian portrayal of God seem to diverge from these ideals, leading to a profound inconsistency that raises a critical question: Should we accept the traditional concept of the Christian God in the absence of a clear and coherent explanation that reconciles these contradictions?

The essence of rational inquiry demands coherence and logical consistency. When presented with an idea, individuals are naturally inclined to evaluate it based on reason, evidence, and internal consistency. In the case of the traditional Christian God, several elements defy logical coherence. For example, the notion of eternal punishment for finite actions or beliefs appears, at its core, to conflict with any meaningful definition of justice. Punishing someone infinitely for limited actions within a single lifetime fails to meet a standard of proportionality, a cornerstone of any fair justice system. If God is indeed the epitome of justice, such disproportionate punishment would be incomprehensible, and any acceptance of it would demand an explanation that aligns this punishment with divine love.

Consider also the issue of belief. Many Christian doctrines suggest that salvation hinges on one’s belief in the Christian God and adherence to specific tenets of Christianity. This claim conflicts with the diversity of human experience and culture, which often shapes beliefs beyond an individual’s control. A child raised in a Hindu or Muslim family may grow up embracing beliefs in good faith that differ from Christianity. If, despite sincere truth-seeking, a person cannot rationally come to accept Christianity, would a loving and just God condemn that individual for their honest convictions? This scenario underscores the need for an explanation that harmonizes divine justice with the reality of human diversity. If no explanation is offered, it raises doubts about the coherence of a God who would penalize individuals for factors largely outside their control.

Given the magnitude of these contradictions, it would be intellectually irresponsible to accept the traditional concept of the Christian God without a clear reconciliation of these issues. Faith without understanding is tantamount to abandoning rationality, and for many, this is an unacceptable cost. Rational minds demand that any being worthy of worship be consistent with reason and fairness. A call to believe in the face of logical contradictions undermines the commitment to truth and rational inquiry that has driven human progress and philosophical thought for centuries.

If no satisfactory explanation emerges from God or those who claim to speak on God’s behalf, then the only reasonable conclusion is to view this concept of God as fundamentally incoherent. In the absence of coherent answers, we must acknowledge that rationality cannot be suspended simply because of appeals to authority or tradition. We cannot accept a deity whose nature and actions defy reason, especially when such defiance implies injustice and cruelty rather than compassion and fairness. Consequently, until coherent explanations resolve these contradictions, it rational to dismiss the traditional depiction of the Christian God as incompatible with a truly loving and just deity.

Leave a comment