Consider the Following:

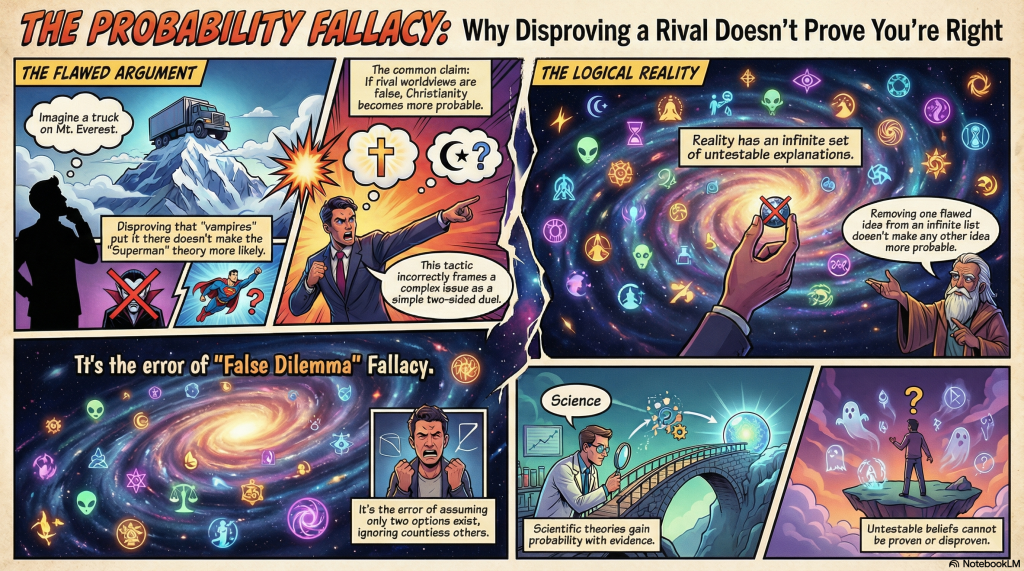

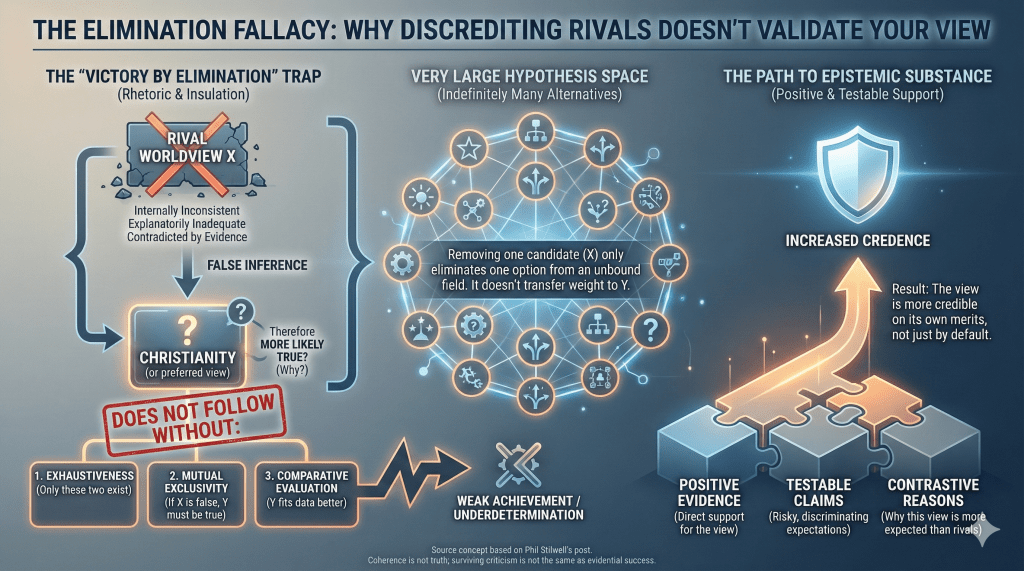

Summary: Demonstrating the incoherency of competing ideologies does not make Christianity more probable, as it remains one of an infinite set of untestable explanations, none of which gain credibility simply by eliminating alternatives. For Christianity to assert epistemic superiority, it must offer testable claims subject to falsification, rather than relying on the failure of competing theories.

Imagine climbers discover a truck on the summit of Mount Everest. This scenario is inherently improbable under any material explanation. Materialistic theories, though conceivable, all appear extraordinarily unlikely. Now, imagine someone proposes that Superman placed the truck there. While Superman’s existence lacks empirical support, the explanation isn’t inherently logically incoherent—after all, Superman has the supposed ability to fly and lift heavy objects. So, does this make Superman the best explanation? Not necessarily.

Compounding this, suppose another group proposes that vampires dropped the truck on the summit, but their claims falter when evidence arises that the truck’s cargo contains garlic, which is known to greatly annoy vampires. The vampire theory becomes self-defeating under its own premises. Does the failure of the vampire theory render the Superman explanation more probable? Not at all. The failure of one implausible theory does not inherently bolster another implausible theory.

Application to Competing Religious Ideologies

Many Christian apologists today adopt this approach: they attempt to debunk competing worldviews, claiming that such debunking increases the probability of Christianity being true. However, this reasoning is flawed. Christianity does not gain credence simply because a competing ideology is shown to be inconsistent. Demonstrating the falsity of another religion (or ideology) does not address the inherent validity of Christianity.

The Infinite Set of Possible Explanations

Consider the set of logically coherent but untestable explanations of reality. This set is theoretically infinite. Humans can invent innumerable gods and accompanying theologies with varying attributes and actions, all beyond empirical scrutiny. For instance, one could propose a god who placed the Everest truck there for some divine reason. Removing one god or explanation from this set by demonstrating its incoherency does not reduce the infinite number of possible explanations. Therefore:

- Debunking one proposed deity (e.g., the vampire-god who hates garlic) does not make another (e.g., Superman or the Christian God) more probable.

- Infinite alternatives remain, meaning the probability of any single explanation (e.g., Christianity) remains vanishingly small.

Testable Versus Untestable Theories

Unlike untestable theories, testable explanations of reality can accrue evidentiary support over time. Scientific theories, for example, face the risk of falsification but gain probability as evidence consistently supports them. Christianity and other untestable belief systems lack this mechanism. If every conceivable event in reality can be explained away by invoking sin, demons, or divine mystery, then Christianity becomes non-falsifiable. A non-falsifiable theory cannot gain probability through rational inquiry, as it remains impervious to testing.

The Core Argument Restated

Let’s formalize the argument more rigorously:

- P1: Christianity is one member of a theoretically infinite set of logically coherent, untestable explanations of reality.

- P2: Debunking any competing explanation in this infinite set does not reduce the size of the set (as new explanations can always be invented).

- P3: Therefore, the debunking of competing explanations does not increase the probability of Christianity being true.

- Conclusion: For every competing ideology demonstrated to be incoherent, the probability of Christianity being true remains unaffected.

Why This Approach Fails

Christian leaders leveraging this tactic may rely on their audience’s lack of familiarity with probability theory or logical principles. By suggesting that every debunked ideology makes Christianity more probable, they create a false dichotomy: that if another explanation fails, Christianity must be the default truth. This tactic ignores the vast space of alternative possibilities and the principle that absence of evidence for one theory does not constitute evidence for another.

A Challenge to Believers

If Christianity is to claim epistemic superiority, it must offer testable claims subject to falsification. Without this, Christianity remains in the same epistemic category as any other untestable ideology, be it Superman, vampires, or newly invented gods. If no empirical evidence can disconfirm its tenets, then its epistemic value is indistinguishable from the countless unsubstantiated alternatives.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the existence of a truck on Mount Everest would most rationally be attributed to some unknown material explanation, even if it remains undiscovered. Similarly, the failure of competing religious ideologies does not validate Christianity or any other belief system. Instead, a material explanation—however elusive—remains the most parsimonious option. Christianity, like the Superman explanation, fails to gain credibility simply by outlasting flawed alternatives.

This principle underpins why debunking competing worldviews does not equate to proving Christianity’s truthfulness. Those promoting such reasoning must acknowledge the infinite possibilities within untestable frameworks and avoid the temptation to declare victory over disproven rivals.

The Logical Form

Argument 1: Eliminating Competing Ideologies Does Not Increase Christianity’s Probability

- Premise 1: Christianity is one member of a theoretically infinite set of logically coherent, untestable explanations of reality.

- Premise 2: The debunking of any competing explanation in this infinite set does not reduce the size of the set, as new explanations can always be invented.

- Conclusion: The debunking of competing explanations does not increase the probability of Christianity being true.

Argument 2: Testable Theories Gain Credibility, Untestable Ones Do Not

- Premise 1: Testable explanations of reality can accrue evidentiary support over time through consistent testing and falsification.

- Premise 2: Untestable explanations, like Christianity, lack the mechanism to gain probability through evidence.

- Conclusion: Christianity remains epistemically equivalent to any other untestable ideology, as it cannot accrue evidence to support its claims.

Argument 3: Failure of Alternatives Does Not Validate Christianity

- Premise 1: The failure of one unsubstantiated explanation does not constitute evidence for another.

- Premise 2: Competing ideologies and untestable belief systems form an infinite set of possibilities.

- Conclusion: The failure of competing ideologies does not validate Christianity or make it more probable.

Argument 4: Christianity Must Be Testable to Claim Epistemic Superiority

- Premise 1: Epistemic superiority requires the ability to make testable claims subject to falsification.

- Premise 2: Christianity’s explanations rely on non-falsifiable constructs, such as sin, demons, or divine mystery.

- Conclusion: Christianity cannot claim epistemic superiority without offering testable claims that can withstand empirical scrutiny.

Argument 5: Parsimony Favors Material Explanations

- Premise 1: When competing explanations fail, the most parsimonious (simplest) explanation should be favored.

- Premise 2: Material explanations, though sometimes undiscovered, do not rely on untestable assumptions like gods or supernatural beings.

- Conclusion: Material explanations remain more rationally plausible than Christianity or any unsubstantiated supernatural explanation.

(Scan to view post on mobile devices.)

A Dialogue

Does Debunking Others Validate Christianity?

CHRIS: If we can demonstrate the incoherency of competing ideologies, wouldn’t that make Christianity more probable? After all, if other explanations fail, doesn’t that leave Christianity as the best option?

CLARUS: Not necessarily. Debunking a competing ideology doesn’t inherently increase the probability of Christianity because it’s just one member of an infinite set of logically coherent but untestable explanations. If you eliminate one possibility, countless others remain, leaving Christianity’s probability unchanged.

CHRIS: But if other systems fail under scrutiny while Christianity remains coherent, doesn’t that give it a stronger foundation?

CLARUS: Not quite. For a claim to gain credibility, it needs to be testable and capable of accruing evidentiary support. Christianity, like many other untestable frameworks, cannot be empirically validated or falsified. Its coherence doesn’t make it any more likely to be true than any of the other countless untestable ideologies.

CHRIS: What about the idea that we can narrow down the possibilities by showing other ideologies to be false? Wouldn’t that reduce the set of alternatives and leave Christianity standing as the most viable explanation?

CLARUS: The problem is that the set of untestable explanations is theoretically infinite. Even if you eliminate one ideology, there’s no limit to how many more can be invented or proposed. Christianity doesn’t gain probability because the set of alternatives never becomes finite.

CHRIS: But isn’t Christianity different because it offers answers that align with people’s experiences and historical events?

CLARUS: That may make it appealing, but it doesn’t make it epistemically superior. To claim epistemic superiority, Christianity must make testable claims subject to falsification. Without this, it remains in the same category as other untestable ideologies, no matter how appealing its narrative might be.

CHRIS: So, are you saying that all belief systems that can’t be tested are on equal footing?

CLARUS: Yes, precisely. An untestable framework is inherently non-falsifiable, so it cannot gain credence in the way a testable scientific theory can. This is why rational inquiry favors material explanations, even when they seem incomplete, because they remain parsimonious and open to scrutiny.

CHRIS: But doesn’t the failure of material explanations sometimes point us toward a supernatural cause?

CLARUS: No, it doesn’t. When material explanations fail, we should still favor parsimony—the simplest explanation that doesn’t rely on untestable assumptions. Inventing supernatural causes like gods or spirits doesn’t add understanding; it only shifts the mystery into an unverifiable realm.

CHRIS: So, what would you require for Christianity to be taken more seriously?

CLARUS: Christianity would need to make specific, testable predictions that could be empirically confirmed or refuted. Without that, it’s just another untestable ideology, no different in epistemic status from countless others.

CHRIS: That’s a challenging standard. But isn’t faith about believing in what can’t be proven?

CLARUS: Faith may be about believing, but that doesn’t make it a reliable epistemic model. Reliance on faith leads to embracing claims without evidence, which is dangerous when seeking truth. Rational inquiry, in contrast, builds confidence based on evidence and testability.

A recap:

Notes:

Helpful Analogies

Analogy 1: The Infinite Puzzle Pieces

Imagine you are handed a puzzle with infinite pieces, but no box or guiding image to show what the puzzle should look like. If you discover that one piece doesn’t fit with another, it tells you nothing about whether any specific piece fits the overall picture. Similarly, demonstrating the incoherency of one ideology doesn’t make Christianity more probable because the set of possible explanations remains infinite. Finding one wrong piece doesn’t clarify the overall solution.

Analogy 2: The Unsolved Crime

Consider a crime scene with multiple suspects but no evidence linking anyone to the crime. Eliminating one suspect because they have an alibi doesn’t make another suspect more likely to be guilty. Instead, it leaves the question unresolved. Similarly, disproving one religious ideology doesn’t automatically validate Christianity; it only narrows a field of infinite possibilities.

Analogy 3: The Lottery of Infinite Tickets

Imagine a lottery with an infinite number of tickets and only one winning ticket. If someone proves that a particular ticket isn’t the winner, this doesn’t increase the chance that your ticket is the winner. The total number of possibilities remains infinite, so the probability of any specific ticket being the winner stays infinitesimally small. Likewise, disproving competing ideologies does nothing to increase the likelihood of Christianity’s truth.

Addressing Theological Responses

Theological Responses

1. The Coherence of Christianity Sets It Apart

Some theologians might argue that while the set of possible explanations is theoretically infinite, few of those explanations are as internally coherent and historically grounded as Christianity. They may claim that its ability to address philosophical, existential, and moral questions in a cohesive framework gives it a higher epistemic standing than other untestable ideologies.

2. Historical Evidence Supports Christianity

Theologians often point to historical evidence—such as the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ—as providing a unique foundation for Christianity. While these events may not be scientifically testable, they argue that historical methodology offers credible support for Christian claims, unlike purely speculative or mythical ideologies.

3. Testability in Spiritual Experience

Some argue that Christianity offers a form of testability through personal spiritual experience and transformation. They may claim that millions of believers have experienced profound changes in their lives, which they attribute to the truth of Christian doctrine, making it qualitatively distinct from other untestable systems.

4. Finite Explanations Have Greater Weight

Theologians might challenge the idea of an infinite set of possible explanations, asserting that most are speculative and lack the depth or cultural influence of Christianity. They may argue that practical finite limitations on plausible explanations make Christianity a more viable candidate than other possibilities.

5. Faith as a Necessary Epistemic Approach

Some might defend faith as a necessary way to access certain truths that lie beyond empirical testing. They could argue that the supernatural realm is inherently beyond the scope of material evidence and that faith provides a valid epistemic model for engaging with this reality.

6. Christianity and Falsifiability

Others might claim that Christianity does have falsifiable components, such as the resurrection of Jesus. They may argue that if strong evidence disproving this central event were discovered, it would falsify the core of Christian belief, suggesting that it is not entirely immune to scrutiny.

7. Cumulative Case Argument

Theologians might assert that Christianity’s coherence, historical basis, and ability to address existential questions form a cumulative case that surpasses other ideologies. Even if debunking alternatives doesn’t directly increase Christianity’s probability, its multifaceted strength makes it more compelling than any single untestable rival explanation.

Counter-Responses

1. Response to “The Coherence of Christianity Sets It Apart”

While Christianity may be internally coherent, coherence alone does not establish truth. Many ideologies, including those in fiction (e.g., elaborate mythologies), are internally coherent but remain entirely unsubstantiated. Without empirical evidence or testability, coherence is simply a minimal requirement for plausibility, not a marker of probability or validity.

2. Response to “Historical Evidence Supports Christianity”

The so-called historical evidence for Christianity, such as the resurrection, is primarily derived from faith-based documents rather than independent, corroborated sources. Claims from the Gospels cannot be considered objective evidence, as they originate within the theological tradition they seek to validate. Historical methodology also cannot establish supernatural events, making these claims inherently unverifiable.

3. Response to “Testability in Spiritual Experience”

Personal spiritual experiences are anecdotal and highly subjective, often influenced by psychological and cultural factors. Such experiences are reported across various religious traditions, including Islam, Hinduism, and others. This demonstrates that such experiences are not unique to Christianity and do not constitute objective evidence of its truth.

4. Response to “Finite Explanations Have Greater Weight”

Limiting the set of plausible explanations to a finite number based on cultural familiarity or historical influence is arbitrary. Theoretical infinity in possible explanations arises from the lack of constraints on untestable claims. If a method is introduced to narrow the set of explanations, it must rely on testability or evidence, which would still exclude Christianity from gaining epistemic weight.

5. Response to “Faith as a Necessary Epistemic Approach”

Faith as an epistemic model undermines rational inquiry because it permits belief without evidence. By accepting faith as valid, one could equally validate conflicting ideologies (e.g., Islam, Norse mythology). This makes faith an arbitrary standard, incapable of adjudicating between competing truth claims.

6. Response to “Christianity and Falsifiability”

While some theologians argue that Christianity is falsifiable (e.g., via disproof of the resurrection), such claims are rarely treated as genuinely refutable by believers. Even if evidence contrary to Christian claims were discovered, faith-based reasoning often reinterprets such evidence to maintain belief. This lack of practical falsifiability undermines the argument that Christianity is genuinely subject to empirical scrutiny.

7. Response to “Cumulative Case Argument”

The cumulative case argument for Christianity assumes that multiple weak arguments together create a strong case, but this is fallacious unless each argument is independently robust. Without empirical evidence or testable predictions, the coherence, historical claims, and existential appeal of Christianity remain insufficient to establish its truth. Such a case is no more compelling than similar claims made by competing religious systems.

Clarifications

The Symbolic Logic Formulation of the Primary Argument

: Christianity is true.

: Competing ideologies are incoherent.

: Christianity asserts epistemic superiority.

: Christianity offers testable, falsifiable claims.

Formulation:

(“For allin the set of explanations

, if

is untestable, the incoherency of

does not imply Christianity’s truth.”)

(“Christianity belongs to an infinite set of untestable explanations.”)

(“If Christianity does not offer testable, falsifiable claims, it cannot assert epistemic superiority.”)

(“The incoherency of competing ideologies does not make Christianity more probable.”)

Combined Conclusion:

(“For all untestable explanations in the set , Christianity cannot assert epistemic superiority without testability, and incoherency of alternatives does not increase Christianity’s probability.”)

A Deeper Explanation

Key Points

- Research suggests that the fallacy here is the false dilemma, where discrediting one ideology implies yours is correct, ignoring other options.

- It seems likely this involves assuming only two choices exist, which is often not true in ideological debates.

- The evidence leans toward this being a common error, especially in politics and religion, though context matters.

Explanation of the Fallacy

The fallacy in question is the false dilemma (or false dichotomy). This occurs when someone acts as though only two options exist when there could be more. In this context, if someone points out flaws in one ideology, they may assume their own must be correct—ignoring other possible ideologies or the chance that none are entirely correct.

Analogies to Make the Point Clear

Restaurant Choice: Imagine three restaurants—A, B, and C. If someone says, “Restaurant B is bad, so Restaurant A must be the best,” they’re ignoring Restaurant C—or the possibility that none are great.

Criminal Trial: If one suspect is proven innocent, that doesn’t prove another specific person is guilty—there could be other suspects or the case might be unresolved.

Career Decision: Saying, “Being a doctor is too stressful, so I’ll be a lawyer,” ignores other careers like teaching or engineering.

These analogies highlight how restricting choices to two can lead to errors in reasoning.

Symbolic Logic Reflecting the Fallacy

The argument typically looks like this:

This form is only valid if those are the only two options. If there are more (e.g., ), the logic breaks down. The correct disjunction should be:

Thus, the fallacy arises when we falsely assume an exhaustive set of options.

Survey Note: Detailed Analysis of the Fallacy in Ideological Comparisons

This analysis addresses the mistaken belief that pointing out incoherencies in one ideology increases the credibility of another. It relies on logical principles and debate strategies to explore the flaw.

This belief often emerges in political campaigns and religious discussions, where attacking the opponent is mistaken for supporting one’s own stance. The root error is a failure to provide positive evidence for one’s own view. The false dilemma emerges when only two options are assumed.

Also worth noting is the fallacy fallacy—dismissing a conclusion as false because the argument for it is flawed. If someone gives a bad argument for ideology B and concludes B is false, that’s the fallacy fallacy. If they then infer A is true, they may also commit a false dilemma.

Clear Explanation of the Fallacy

A false dilemma arises when one claims, “If B is flawed, A must be true,” ignoring other alternatives like C, D, or a hybrid view. This neglects the need for direct evidence for A.

Examples:

- “Socialism has failed, so capitalism is the answer” (ignores other systems like social democracy).

- “That religion has inconsistencies, so mine must be true” (ignores agnosticism or other beliefs).

Each ideology must be evaluated independently.

Analogies

Restaurant Choice: “Restaurant B is bad, so A must be best” excludes C or others.

Criminal Trial: Clearing one suspect doesn’t confirm another suspect’s guilt.

Career Decision: Rejecting one path doesn’t validate another without exploring the full range of options.

These analogies make the fallacy intuitive.

Symbolic Logic Reflecting the Fallacy

Here’s a formal disjunctive syllogism:

This is only valid if is exhaustive. But in a false dilemma:

In ideological terms:

Only valid if B and A are the only possible ideologies. But if there are others:

This shows how the fallacy results from ignoring alternatives.

Unexpected Detail: Connection to Debate Tactics

This fallacy is commonly used in debate tactics, where speakers simplify complex issues into binary choices to persuade audiences. In political discourse, candidates often attack one option to imply theirs is the only viable one—reinforcing the false dilemma and misleading the audience.

Table: Comparison of Logical Errors

| Aspect | Belief (Discrediting B Makes A More Probable) | False Dilemma | Fallacy Fallacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reasoning Step | Flaws in B imply A is true | Assumes only B or A, ignores C, D, etc. | Flaws in B’s arguments mean B is false |

| Logical Error | Assumes comparison strengthens own position | Limits options to two when more exist | Rejects B’s truth due to argument flaws |

| Outcome | Weakens B, assumes strengthening A | Concludes A from ¬B, ignoring other options | Concludes B is false, supports A |

| Example | Criticizing socialism implies capitalism is best | “Socialism fails, so capitalism wins” | Bad argument for socialism = socialism is false |

Conclusion

In sum, the false dilemma fallacy is at play when someone concludes that their ideology must be correct simply because another is flawed—ignoring other possible alternatives. Symbolic logic shows this is an invalid inference unless the disjunction is exhaustive. The analysis also connects the fallacy to common debate tactics and persuasive framing, making this fallacy both logically and rhetorically significant.

Leave a comment