How a Circular Defense Mechanism Undermines Intellectual Honesty

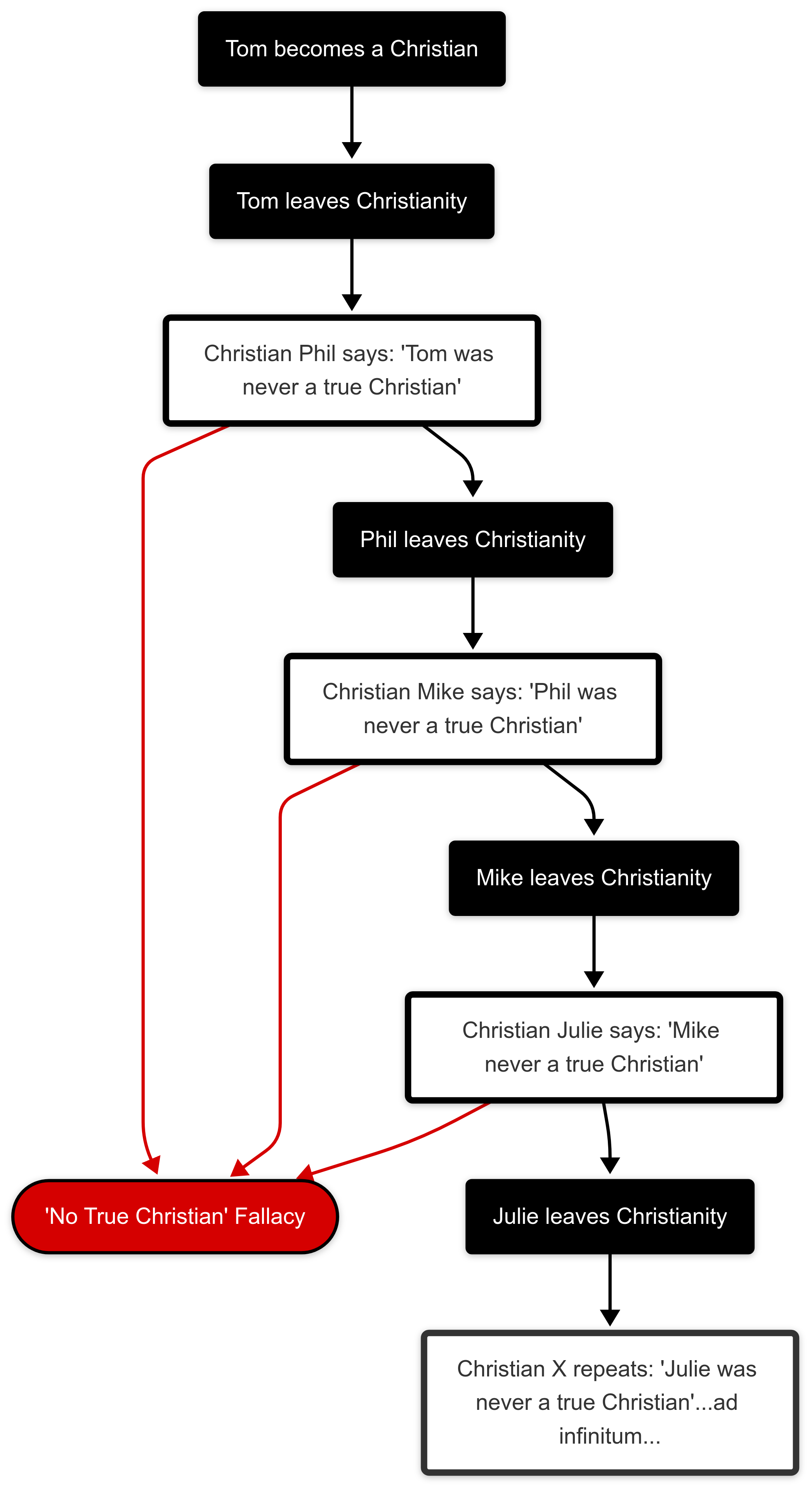

The “No True Christian” fallacy—a specific instance of the No True Scotsman fallacy—is a rhetorical escape hatch used by some Christians to protect the coherence and ideal image of their belief system. As clearly depicted in the uploaded diagram, the fallacy takes the following form: when an individual who once professed belief in Christianity leaves the faith, current believers retroactively claim that the person “was never a true Christian.” This assertion is not only logically incoherent but functions as a defensive psychological mechanism to insulate the faith from rational scrutiny.

The Core Incoherence: Shifting Definitions

The most obvious incoherence lies in the self-modifying definition of what it means to be a “true Christian.”

- A person professes belief, engages in worship, studies the Bible, prays, evangelizes, and dedicates years to Christian living.

- Upon deconversion, their past devotion is dismissed as inauthentic because they left.

This retrospective reinterpretation is not based on any observable metric, but solely on the inconvenient fact that the individual ceased believing. It renders the term “true Christian” impervious to falsification, which is epistemically irresponsible. If no amount of sincere belief, obedience, or spiritual transformation counts once someone exits the faith, then the term becomes vacuous—a floating signifier unanchored from any behavioral or experiential anchor.

The Recursive Trap: Everyone Becomes a Heretic

As seen in the diagram, the fallacy inevitably consumes its own defenders.

- Phil says Tom was never a true Christian.

- Phil leaves. Mike says Phil was never a true Christian.

- Mike leaves. Julie says Mike was never a true Christian.

- And so on.

This recursive sequence shows that the very people who make the accusation are vulnerable to the same dismissal, often within the span of a few years or decades. Thus, today’s gatekeeper becomes tomorrow’s apostate. If each person who leaves was “never a true Christian,” then at some point all former Christians were “never true Christians,” which entails that the vast majority of Christianity was composed of false Christians—an absurd conclusion that collapses any attempt to measure authenticity.

A Shield Against Honest Engagement

They went out from us, but they did not really belong to us. For if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us; but their going showed that none of them belonged to us. — 1 John 2:19

Beyond its logical failings, the fallacy serves a tactical purpose:

It protects the believer from the discomfort of examining why people leave.

This is critical. Former Christians often leave for reasons grounded in:

- Contradictions in Scripture

- Ethical concerns with the character of the biblical God

- Scientific understanding incompatible with Genesis accounts

- Historical failures of prophecy

- Psychological harm caused by doctrines like eternal damnation

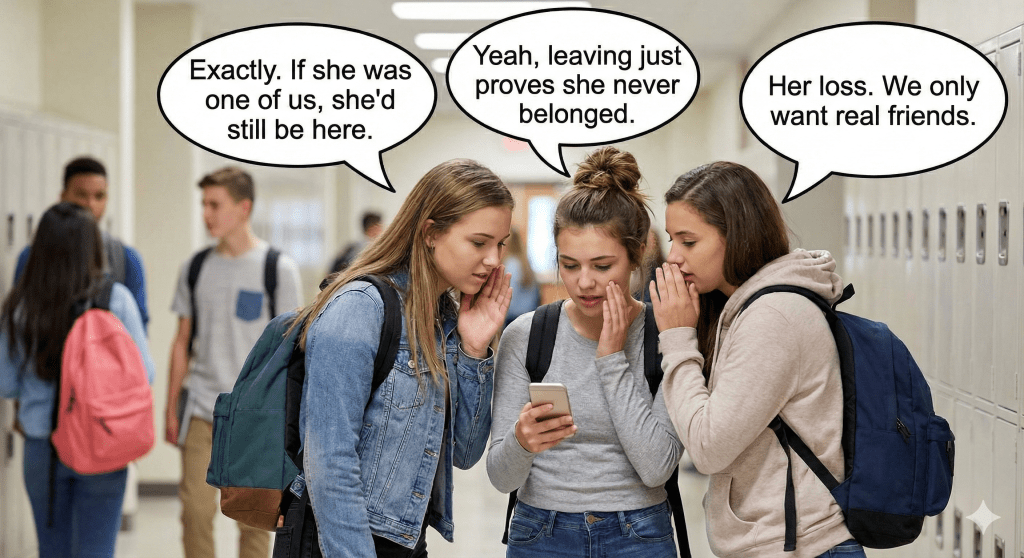

But instead of grappling with these critiques, Christians who deploy this fallacy dismiss the critic entirely. If the ex-Christian “was never one of us,” then there’s no need to ask why they left or whether their objections have merit. This strategy depersonalizes dissent, transforming it into a problem of spiritual fraud rather than theological inadequacy.

Faith in a Fortress of Air

Ironically, this approach portrays Christianity not as robust, but as fragile—a worldview so delicate that it must constantly reclassify dissenters to protect itself.

- If Christianity is true, it should withstand deconversion narratives.

- If it is rational, it should welcome critical examination.

- If it is coherent, it shouldn’t need to revise its definition of “true believer” after every defection.

The “No True Christian” fallacy betrays an insecurity at the heart of the faith: a fear that those who leave might have good reasons for doing so, reasons that could unravel the beliefs of those still within.

Conclusion

The “No True Christian” fallacy is not only circular and incoherent, but also strategically employed to avoid honest dialogue. It delegitimizes ex-believers, thus shielding current believers from engaging with critical arguments that may threaten their worldview. This intellectual bypass is not an act of faithfulness, but of epistemic cowardice—a refusal to follow the evidence wherever it leads.

If Christianity is to have any claim to truth, it must dispense with this fallacy and begin listening to those who, having walked the path of faith, now choose a different route not out of rebellion, but from hard-earned conviction.

Leave a reply to Ron Cancel reply