The notion of the “image of God” (Imago Dei) has historically served as a conceptual wildcard for Christian theology, invoked to ground everything from human dignity to environmental responsibility to social justice—often without a coherent or consistent definition. While pastors have invoked it casually from pulpits and apologists have marshaled it opportunistically in debates, scholars themselves have failed to secure a stable meaning. Before appealing to the image of God to support claims like “the senile deserve dignity” or “humans have dominion over animals,” it is essential to establish what exactly the “image” entails.

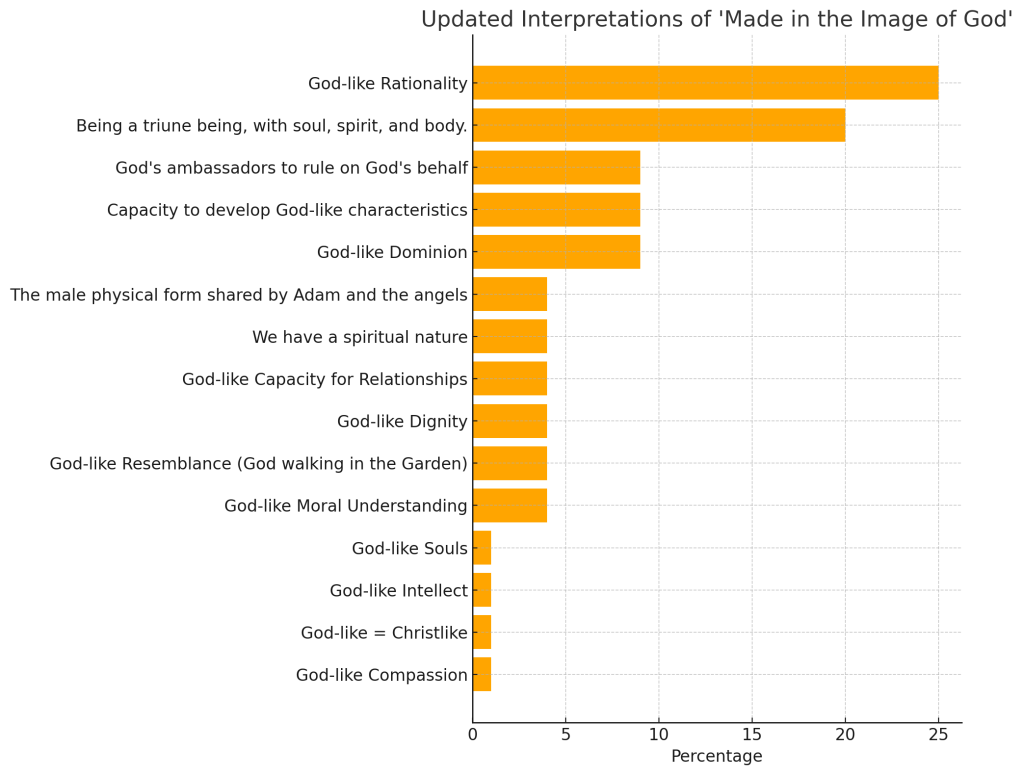

Throughout Christian history, at least ten major definitions of the “image of God” have been proposed:

- Substantive View: The image consists of certain inherent qualities (e.g., rationality, moral reasoning, spirituality).

- Relational View: The image is the capacity for relationship, especially reflecting the relationality of the Trinity.

- Functional View: The image is expressed in actions—particularly dominion and stewardship over creation.

- Christological View: The image is Christ himself; humans reflect this image to the degree that they conform to Christ.

- Vocational View: The image represents a calling or commission to act as God’s agents in the world.

- Ontological View: The image resides in the very being of humanity, regardless of attributes or actions.

- Communal View: The image is best displayed in human community and relational interaction.

- Dynamic View: The image is a process of becoming, realized through moral and spiritual development.

- Imago Dei and Social Justice View: The image implies universal human rights and inherent dignity.

- Biblical Literalism: The image implies physical resemblance to God, based on a literal reading of Genesis.

The divergence among these views highlights the enormous conceptual plasticity of the “image of God.” Without anchoring the term in a clear definition, its invocation in any theological or ethical context risks circularity, equivocation, and rhetorical sleight of hand.

Christian Apologetics Facebook Group Survey: 62 votes.

How Apologists Shift Between Conflicting Notions of the “Image of God”

In apologetic discourse, it is commonplace for apologists to invoke one definition of the image of God to establish a claim, then implicitly shift to another definition when the first becomes problematic. Here are expanded examples of this opportunistic shifting:

Example 1: Defending Human Dignity vs. Justifying Animal Dominion

- Initial Context: In defending the dignity of people with severe dementia, an apologist might lean heavily on the Ontological View—the claim that the image of God is intrinsic and unrelated to mental faculties. Thus, even if a human loses memory, reason, or communication ability, they still bear the image fully.

- Shifted Context: However, when distinguishing humans from animals, the same apologist might pivot to the Substantive View, arguing that rationality and moral awareness mark the unique image of God in humanity.

- Conflict: If rationality is the mark of the image, then humans who lose rational capacity (e.g., infants, those in comas, dementia patients) would seem to lose the image—a result apologists must resist. Thus, two incompatible definitions are employed to serve two different rhetorical ends.

Example 2: Promoting Environmental Stewardship vs. Defending Human Supremacy

- Initial Context: When encouraging environmental care, apologists might cite the Functional View, emphasizing that humanity’s dominion is stewardship, reflecting God’s benevolent governance over creation.

- Shifted Context: Yet, when confronted by critics who say humans have abused nature, apologists often slip into a Vocational View, suggesting that dominion is not merely functional action but a God-given vocation, regardless of performance. Stewardship becomes an ideal standard rather than a current functional trait.

- Conflict: If dominion is a functional reflection of God’s care, then ecological destruction should imply a loss of imaging God. But if dominion is vocational, then the image persists regardless of behavior. Again, the apologist shifts definitions to insulate the doctrine from criticism.

Example 3: Theological Anthropology vs. Christology

- Initial Context: In generic theology of humanity, the Ontological View or Substantive View often frames humans as created in God’s image from the start, prior to any religious belief or development.

- Shifted Context: However, in Christocentric theological systems, the Christological View surfaces, asserting that the true image of God is only realized in conformity to Christ.

- Conflict: If the image is ontologically present in all from birth, how can it also be said that the image is realized only through Christ? If only Christians bear the full image, then non-Christians are arguably “less” in the image—an implication most apologists resist but implicitly flirt with when switching definitions.

Example 4: Arguing for Universal Human Rights vs. Arguing for Hell

- Initial Context: When advocating for universal human rights, the Imago Dei and Social Justice View is paramount: every human bears the image of God and thus deserves dignity, care, and equality.

- Shifted Context: Yet when justifying eternal conscious torment in hell, the apologist may retreat to a view of the imago Dei that is marred, corrupted, or forfeited by sin.

- Conflict: If human dignity rests on the undiminished image of God, then eternal damnation of billions becomes grotesquely disproportionate. If the image is forfeited by sin, then the basis for universal dignity collapses. The apologist must dance carefully—or inconsistently—between notions of an indelible and a conditional image.

Critical Observations

- Equivocation Without Acknowledgment: The same phrase “image of God” is used across different arguments but means different things each time. This is a textbook case of equivocation, where a term subtly changes its meaning midstream.

- Strategic Elasticity: Because “the image of God” is so nebulous, it can be strategically expanded, contracted, or shifted depending on the apologetic need. This is not principled theology; it is adaptive rhetoric.

- Failure of Theological Coherence: A theological concept meant to anchor deep truths about humanity instead becomes a rhetorical Swiss army knife, employed whenever useful, without internal coherence.

- Undermining Credibility: Invoking contradictory definitions of the same term undermines the credibility of the theological system that claims divine origin, internal consistency, and supreme rationality.

Conclusion

Without a clear, consistent, and principled definition of the “image of God,” theological and apologetic invocations of it are rhetorically convenient but logically unstable. What ought to be a profound anchor of theological anthropology too often functions as an opportunistic and unprincipled expedient. If Christian theology wishes to maintain intellectual credibility, it must discipline its use of such foundational concepts rather than stretching them to fit every polemical need.

Do Humans More Reflect the Image of God or of Animals?

In theological discourse, the image of God (Imago Dei) is often portrayed as what uniquely separates humanity from the animal world. However, if we scrutinize each major definition of the “image of God,” we find that human beings align far more closely with animals than with the traditional notion of a transcendent God. Below is a rigorous analysis of how each view of the image fares under this comparison.

1. Substantive View

(Image = inherent human qualities such as rationality, moral capacity, spirituality)

- Claim: Humans uniquely possess rationality, moral awareness, and spirituality, reflecting divine traits.

- Reality:

- Animals demonstrate rational behaviors (e.g., problem-solving in corvids and primates).

- Moral-like behaviors such as fairness and empathy are observed in chimpanzees, elephants, and dolphins.

- Spiritual behaviors (e.g., mourning rituals) are observed in elephants and apes.

Thus, on the substantive scale, humans resemble advanced animals more than any transcendent divine rationality or morality.

2. Relational View

(Image = capacity for relationships, mirroring the Trinity’s relational nature)

- Claim: Humans mirror God by forming complex relationships.

- Reality:

- Social bonds in elephants, wolves, primates, and cetaceans display remarkable depth and loyalty.

- Altruism, cooperation, and emotional communication are not uniquely human.

Thus, relationally, humans are best understood as highly social animals, not qualitatively distinct reflections of divine communion.

3. Functional View

(Image = exercising dominion and stewardship over the earth)

- Claim: Humans function as caretakers and rulers over creation.

- Reality:

- Dominion in human hands often manifests not as stewardship but exploitation and ecological destruction.

- Functional dominion (territory control, resource management) is also found in animal species (e.g., wolf packs, chimpanzee troops).

Thus, humanity’s “dominion” echoes animalistic competition and territory control, not responsible divine governance.

4. Christological View

(Image = likeness to Christ; humans reflect God as they conform to Christ)

- Claim: The true image of God is the character and life of Jesus Christ.

- Reality:

- Very few humans approach the selfless, sacrificial, and forgiving ideals attributed to Christ.

- Human behavior—marked by self-interest, tribalism, and violence—resembles animal survival instincts far more than Christlike altruism.

Thus, in practice, humanity mirrors the competitive and self-preservational tendencies of animals, not the idealized character of Christ.

5. Vocational View

(Image = divine appointment to fulfill a role or mission on earth)

- Claim: Humans bear God’s image by fulfilling divine purposes.

- Reality:

- Most human behavior is geared toward survival, reproduction, and resource acquisition, just like in animals.

- The idealized “mission” is often subverted by self-interest and tribal loyalties.

Thus, humanity’s dominant activities are better explained by evolutionary imperatives, aligning humans with the animal kingdom rather than any high divine vocation.

6. Ontological View

(Image = intrinsic being; humans reflect God simply by existing as human)

- Claim: Human essence itself mirrors divine being.

- Reality:

- Biologically, humans are mammals sharing over 98% DNA with chimpanzees and displaying fundamentally animalistic needs and behaviors.

- There is no empirical sign that human essence is categorically distinct from that of animals.

Thus, ontologically, humans are better viewed as evolved primates rather than beings of divine essence.

7. Communal View

(Image = expressed in human community and relationships)

- Claim: Humanity images God in forming communities and social structures.

- Reality:

- Animal groups such as wolf packs, elephant herds, and dolphin pods exhibit complex community structures, cooperative hunting, collective child-rearing, and mourning rituals.

Thus, communal life links humans more closely with social animals than with any singular divine model.

- Animal groups such as wolf packs, elephant herds, and dolphin pods exhibit complex community structures, cooperative hunting, collective child-rearing, and mourning rituals.

8. Dynamic View

(Image = a developmental process of growing into God’s likeness)

- Claim: Humans progressively become more God-like through moral and spiritual development.

- Reality:

- Human societies fluctuate between cooperation and brutality; moral development is halting, uneven, and often regressive.

- Evolutionary psychology explains incremental moral learning as adaptive social behavior, not divine progression.

Thus, the dynamic process reflects gradual animal social evolution far more than any clear movement toward divine likeness.

9. Imago Dei and Social Justice View

(Image = basis for asserting universal dignity and rights)

- Claim: Every human, by virtue of the image, deserves equal dignity.

- Reality:

- Throughout history, humans have enslaved, oppressed, exploited, and exterminated each other on scales unknown among animals.

- Animals, by contrast, rarely engage in widespread, purposeless cruelty outside survival contexts.

Thus, historically and practically, humans often degrade one another more than they embody any innate, divine dignity.

10. Biblical Literalism

(Image = physical resemblance to God)

- Claim: Humans somehow physically resemble God.

- Reality:

- Humans are physically indistinguishable from other primates in terms of anatomical structure, organ systems, and physiology.

- Our bodies clearly belong to the animal kingdom and bear no transcendent physical traits.

Thus, if the image were physical, humans look like slightly modified primates, not anything plausibly resembling a transcendent deity.

Conclusion

✶ When subjected to careful scrutiny, every major view of the “image of God” reveals that humans more closely resemble the animal world—both structurally and behaviorally—than anything worthy of being called divine.

- In rationality, we mirror apes.

- In relationships, we mirror social mammals.

- In dominion, we mirror territorial animals.

- In moral development, we mirror evolutionary group survival strategies.

- In physical form, we mirror primates.

Thus, whatever “the image of God” was supposed to mean, humans—when honestly assessed—display continuity with animals, not resemblance to divinity.

The following is an Opus 4.5 assessment on the proximity of the image of humans to the image of God or of animals across various dimensions that apologist invoke as the Imago Dei referred to in Scriptures.

Leave a comment