The Logical Failure of Omitting Resurrection Probability While Claiming It is “Most Probable”

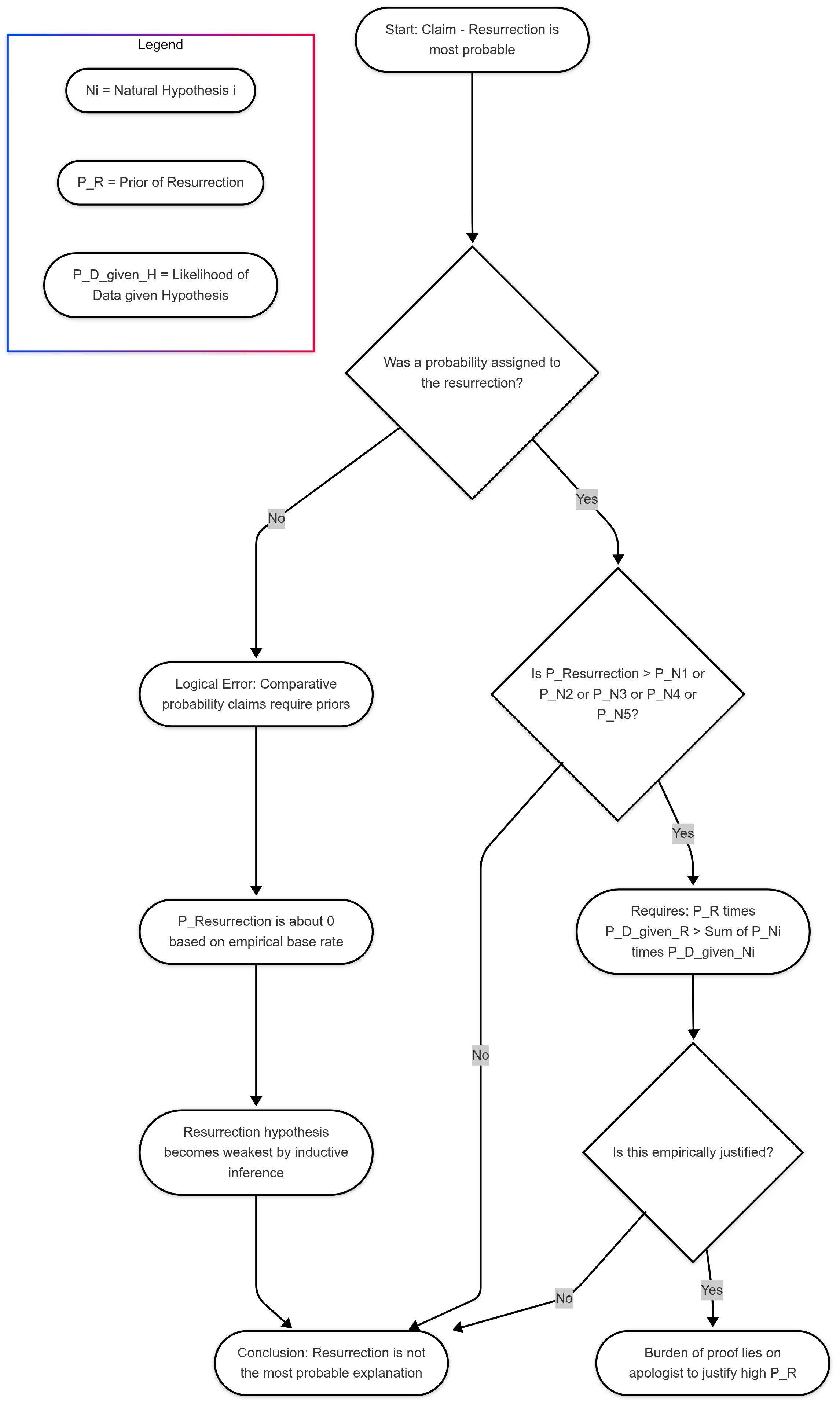

One of the most foundational requirements of rational discourse—especially when adjudicating between competing explanatory hypotheses—is the assignment of relative probabilities. Without this, no comparative claim can be meaningfully asserted. Yet in Christian apologetics, it is not uncommon to encounter the claim that “the resurrection is the most probable explanation” of the empty tomb or the post-crucifixion reports—without any numerical or inferential probability being assigned to the resurrection hypothesis itself. This omission is not merely an oversight; it is a categorical violation of rational inference and epistemic responsibility. This essay will detail the logical implications of this omission and demonstrate why such claims collapse under scrutiny.

Why Probabilistic Comparison Requires All Terms

In any evaluation of competing explanations, Bayesian reasoning provides the normative standard. Bayes’ Theorem is formally represented as:

Where:

is the posterior probability of the hypothesis given the data

is the likelihood of observing the data assuming the hypothesis is true

is the prior probability of the hypothesis

is the total probability of observing the data under all hypotheses

In the case of the resurrection, defenders often highlight anecdotal or testimonial evidence (e.g., post-crucifixion appearances, conversions, eyewitness claims) and argue that these are best explained by Jesus rising from the dead. But unless one specifies —the prior probability—the formula breaks down. The comparison to other hypotheses becomes meaningless.

One cannot validly say, “H is more probable than A, B, C, D, and E” unless and

are provided and shown to exceed the respective values of

, etc.

The Resurrection’s Incoherent Probability Default

What is the value of ? Given all documented human history, where the base rate of biologically dead individuals returning to life is zero, this yields:

This does not imply metaphysical impossibility, but it does establish an empirical prior probability that is functionally infinitesimal. The apologetic strategy, however, frequently evades this issue and instead pretends the prior is unspecified or irrelevant. This is epistemically incoherent. One must address the resurrection’s base rate if one is to include it in any comparative analysis.

Disjunction of Natural Hypotheses

Consider the five most common naturalistic theories:

- Stolen body by disciples

- Stolen body by robbers

- Wrong tomb

- Apparent death (swoon theory)

- Never buried (body discarded or destroyed)

Suppose each is given a minimal probability of 0.1%:

Then the disjunction (i.e., the chance that at least one is true) is:

Even at highly conservative estimates, this value dwarfs the resurrection’s prior.

Formal Logic Summary

Let:

= Resurrection hypothesis

= Naturalistic hypotheses (for i = 1 to 5)

= Data (e.g., empty tomb, post-crucifixion appearances)

Then the apologetic claim is:

But without assigning a value to , this statement is void. In fact, using Bayesian calculus:

So the comparison depends entirely on the ratio:

Without specifying , the apologist is making an invalid comparative assertion.

Conclusion: Neglecting Resurrection Probability Invalidates the Claim

In summary:

- The claim that “the resurrection is the most probable explanation” requires a quantified or at least reasoned

.

- This requirement is consistently ignored or evaded in apologetic arguments.

- Since the base rate of resurrections is effectively zero, any minimally probable natural theory will, in sum or individually, exceed the resurrection in probability.

- Therefore, the failure to provide a resurrection probability is not a minor lapse—it is a logical disqualification from making any comparative claim of probability.

Until the resurrection hypothesis is given a coherent probability assignment, any argument that it is “most probable” must be dismissed as epistemically incoherent and logically invalid.

Leave a comment