An Epistemological Critique of the Definitions of Πίστις in Hebrews 11:1

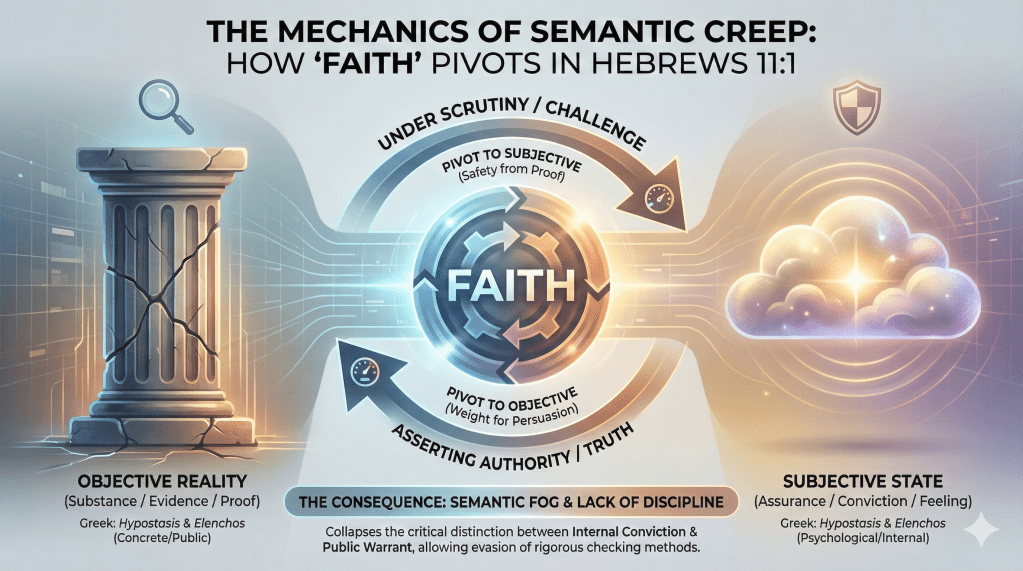

The Greek term πίστις (pistis), often translated as “faith,” is central to the theological discourse in Hebrews 11:1, which states: “Ἔστιν δὲ πίστις ἐλπιζομένων ὑπόστασις, πραγμάτων ἔλεγχος οὐ βλεπομένων.” Translated, this reads: “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (KJV). The verse employs two key terms, ὑπόστασις (hypostasis) and ἔλεγχος (elenchos), to define πίστις. Interpretations of ὑπόστασις in this context, particularly as articulated by Steve Henk’s citation of Strong’s Concordance, propose three meanings: (1) an ontological foundation or substance, (2) psychological assurance or confidence, and (3) a legal title or guarantee. This essay rigorously examines these definitions against modern standards of rational epistemology, which require that a belief’s degree of certainty corresponds to the degree of relevant evidence. Each proposed definition is found to be logically incoherent or epistemically unsound, failing to provide a robust basis for understanding πίστις.

Rational Epistemology and Belief

Rational epistemology holds that justified belief should be proportionate to the strength and quality of evidence. Beliefs lacking evidential grounding or relying on circular reasoning are epistemically deficient, as they cannot reliably guide decisions in contexts requiring probabilistic reasoning, such as poker or life’s uncertainties. In poker, for instance, betting heavily on a weak hand due to unwarranted confidence often leads to loss; similarly, in life, decisions grounded in unverified beliefs can yield suboptimal outcomes. With this framework, we evaluate the three proposed definitions of πίστις as ὑπόστασις.

Critique of Definition 1: Ontological Foundation (Substance)

The first definition posits πίστις as the “ontological foundation” or “substance” of things hoped for, suggesting that faith itself constitutes a real, underlying basis for future expectations. This interpretation, rooted in the etymology of ὑπόστασις (from hypó, “under,” and hístēmi, “to stand”), implies that faith is the groundwork or essence of hoped-for realities.

Logical Incoherence

This definition is circular and thus logically incoherent. If πίστις is fundamentally a belief—a cognitive state of accepting a proposition as true—defining it as the “substance” of what is hoped for suggests that the belief itself is the evidence or foundation for the belief’s object. This is akin to saying, “I believe X because I believe X has substance.” Such circularity fails to provide an independent evidential basis for the belief, violating the epistemological requirement that evidence must be external to the belief itself. For example, believing a poker hand is strong because of the belief itself, without reference to the cards, is irrational and likely to lead to poor outcomes.

Epistemic Deficiency

Ontologically, claiming that πίστις creates a “real underlying basis” for unseen realities assumes the existence of those realities without evidence. In rational epistemology, existence claims require empirical or logical support. Without such support, this definition conflates the act of believing with the reality of the believed, rendering it epistemically unsound. It cannot justify πίστις as a reliable guide for action, as it lacks a mechanism to verify the hoped-for outcomes.

Critique of Definition 2: Psychological Assurance (Confidence)

The second definition frames πίστις as psychological assurance or inner confidence in unseen realities. This interpretation emphasizes the subjective conviction that accompanies faith, portraying it as a mental state of certainty.

Epistemic Flaw

Psychological confidence, when detached from evidence, is epistemically flawed. Rational epistemology demands that confidence in a belief corresponds to the strength of relevant evidence. For instance, in poker, a player’s confidence in a bluff must be calibrated to the likelihood of success based on observable cues (e.g., opponents’ behaviors, card probabilities). Confidence in unseen realities, as proposed here, lacks such grounding. If πίστις is merely a feeling of certainty about unverified propositions, it risks overconfidence, leading to decisions that are irrational and prone to error. In life, as in poker, acting on unwarranted confidence—without assessing evidence—consistently produces inferior outcomes.

Lack of Epistemic Warrant

This definition fails to bridge the gap between subjective certainty and objective truth. Confidence alone does not make a belief true or justified. For example, a person may feel confident in a false prophecy, but this does not validate the prophecy. Without an evidential tether, πίστις as psychological assurance cannot meet the standards of rational epistemology, as it prioritizes emotion over reason.

Critique of Definition 3: Legal Title (Guarantee)

The third definition interprets πίστις as a “legal title” or “guarantee” to future fulfillment, akin to a title-deed ensuring possession of promised realities. This draws on the Hellenistic use of ὑπόστασις as a legal term for a claim or contract.

Logical and Epistemic Failure

This definition asserts that πίστις itself guarantees the reality of what is hoped for. However, a belief cannot inherently guarantee its object’s existence or fulfillment. For instance, holding a title-deed to property assumes the property exists; similarly, claiming πίστις as a guarantee presupposes the reality of the promised outcome. This assumption is epistemically unwarranted without independent evidence for that outcome. In rational terms, a belief remains a belief—a cognitive stance—regardless of how strongly it is held or framed as a “title.” It cannot serve as a guarantee, as it lacks the causal or evidential power to ensure the promised reality.

Practical Implications

In practical contexts, treating πίστις as a guarantee is akin to betting all-in in poker based on a promised but unverified card. Such actions are reckless, as they rely on hope rather than evidence. The definition fails to provide a mechanism by which πίστις can reliably secure future outcomes, rendering it epistemically unsound.

Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the epistemological shortcomings of each definition:

| Definition | Proposed Meaning | Logical Issue | Epistemic Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontological Foundation | Substance of things hoped for | Circular: Belief as evidence for itself | Lacks independent evidence; assumes existence of hoped-for realities |

| Psychological Assurance | Inner confidence in unseen realities | None (not inherently circular) | Confidence detached from evidence; risks overconfidence and poor decision-making |

| Legal Title | Guarantee or title-deed to fulfillment | Assumes outcome without evidence | Belief cannot guarantee reality; lacks evidential basis for promised outcomes |

Influence of Greek Philosophy and Jewish Texts

The interpretation of ὑπόστασις may draw from Greek philosophy (e.g., Stoic or Platonic notions of substance) or Jewish texts (e.g., Wisdom of Solomon), where it can denote essence or confidence. However, these influences do not resolve the epistemological issues. Greek philosophy often required empirical or rational grounding for claims about reality, which the ontological and legal interpretations lack. Jewish texts emphasizing trust in divine promises still require evidence of divine reliability, which πίστις as a belief cannot itself provide. Thus, these cultural contexts do not salvage the definitions from their logical and epistemic flaws.

Conclusion

The three proposed definitions of πίστις as ὑπόστασις in Hebrews 11:1—ontological foundation, psychological assurance, and legal title—fail to meet the standards of rational epistemology. The ontological definition is circular, equating belief with its own evidence. The psychological definition prioritizes subjective confidence over evidential grounding, risking irrationality. The legal definition assumes unverified outcomes, rendering πίστις an unreliable guarantee. In contexts requiring probabilistic reasoning, such as poker or life, these definitions lead to epistemically deficient decisions. A coherent and sound definition of πίστις must align belief with evidence, ensuring that faith is not mere wishful thinking but a justified stance supported by reason and observation.

It is strongly suggested that Hebrews 11:1 reflects a failure of the Bible to establish or reflect an notion of faith that is logically or epistemically coherent, undermining the fundamental premise of Christianity.

Leave a reply to Phil Stilwell Cancel reply