The Gospel Writers’ Curious Delay:

Why Wait Decades to Document the Divine?

In a sun-drenched courtyard in Ephesus, circa AD 53, four men—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—lounged on cushions, sipping watered wine and nibbling olives. Amid clinking clay cups and the bleat of a stray goat, Luke posed a question that should have been obvious: “Has anyone written it down?” By “it,” he meant the crucifixion, the empty tomb, the resurrection of Jesus, and—oh, by the way—the bizarre moment when dead saints reportedly climbed out of their graves and strolled into Jerusalem like it was a festival day. The awkward silence that followed, as imagined in a playful dialogue, revealed a startling truth: two decades after the events that changed the world, none of these Gospel writers had bothered to record them. This raises a peculiar question: why did the Gospel writers wait so long to document the most earth-shattering events in history? And why, when they finally did, did only one of them mention a zombie-like parade that should’ve been the talk of the town? Moreover, if the Bible is the word of a God who desired His will and identity to be unequivocally known, why weren’t these events immediately and unequivocally recorded?

The Great Papyrus Procrastination

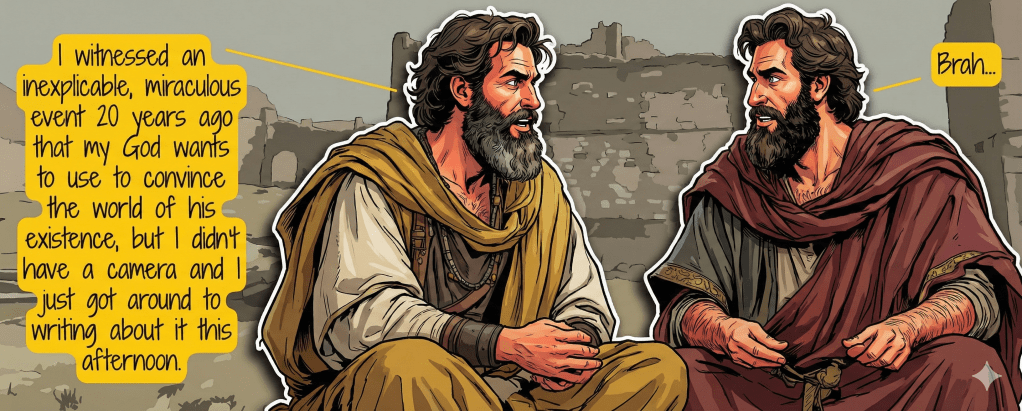

The earliest Gospel, Mark’s, likely appeared around AD 65–70, a full 30–35 years after Jesus’ death and resurrection around AD 30–33. Matthew and Luke followed in the 80s, and John lagged even further, possibly into the 90s. To put that in perspective, imagine waiting until 2025 to write the first account of 9/11 or the moon landing. Memories fade, details blur, and stories morph—yet these were the events that launched a global religion. As Luke pointed out in our imagined dialogue, “We’re saying God incarnate was murdered, rose from the dead, walked around for forty days… and not one of us thought, ‘Hmm, maybe I should jot that down before I forget whether it was a Sunday or a Monday’?”

This delay is odd for several reasons. First, writing was not uncommon in the first century. Jewish scribes, Roman bureaucrats, and Greek philosophers were prolific, documenting everything from tax records to omens. Second, the early Christians were a literate bunch, with figures like Paul churning out letters faster than a modern-day influencer posts on X. Yet the defining story of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection remained unwritten for decades, left to oral tradition in a game of divine telephone. Mark’s excuse in the dialogue—“I was going to, but Paul dragged me to Cyprus!”—pokes fun at this, but it underscores a real puzzle: why the procrastination?

The Zombie Apocalypse That Wasn’t

The oddity deepens with one particular detail: the resurrection of the saints. According to Matthew 27:52–53, when Jesus died, “the tombs broke open, and the bodies of many holy people who had died were raised to life. They came out of the tombs after Jesus’ resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many people.” This is no minor footnote—it’s a mass resurrection, a scene straight out of a first-century thriller. Yet, only Matthew mentions it. Mark, Luke, and John, writing their own accounts, say nothing. In our imagined dialogue, Mark even blurts, “Wait, that actually happened?” while John muses about framing it as a “divine procession of the formerly deceased.” Their confusion mirrors a historical conundrum: if dead people wandered into Jerusalem, why is the evidence so sparse?

You’d expect a mass resurrection to leave a paper trail wider than the Appian Way. Families would’ve wept and written about their miraculously returned loved ones. Neighbors would’ve gossiped. Religious leaders, especially those hostile to Jesus’ movement, would’ve penned furious rebuttals. Yet, the historical record is silent. Josephus, a Jewish historian who chronicled everything from rebellions to quirky sects, never mentions it. Tacitus, a Roman who loved a good supernatural tale, is mute. Pliny the Elder, who cataloged every oddity from two-headed calves to eclipses, skips it. Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher writing reams about first-century Jewish life, has nothing to say. As Luke might’ve groaned, “That’s a bit… zombie apocalypse! And no one thought that merited a footnote?”

A God’s Will Left to Chance?

If the Bible is the inspired word of a God who intended His identity and will to be unequivocally known, the delay in documenting these events is baffling. A deity with such a goal would presumably ensure immediate and unequivocal records—divinely inspired accounts written on the spot, free of contradictions or omissions. Imagine God, having orchestrated the crucifixion, resurrection, and a mass raising of saints, whispering to Matthew, “Quick, grab a stylus—don’t let this one slip!” Yet, instead, we get decades of silence, with the Gospel writers lounging in Ephesus, bickering over angels versus glowing men. If God’s will was to be clearly known, why rely on fallible humans waiting 20–60 years to write accounts that don’t even agree on a zombie parade? This delay and inconsistency suggest either a divine plan that embraces ambiguity or a human process of storytelling, not a perfectly orchestrated revelation.

Why the Silence?

The absence of external corroboration is striking. If “many saints” rose and “appeared to many,” as Matthew claims, their return should’ve sparked a frenzy. Imagine your long-dead Uncle Zechariah knocking on your door, looking “surprisingly spry for a corpse,” as Matthew quips in the dialogue. You’d write a letter, carve an inscription, or at least tell everyone at the synagogue. Yet no such accounts exist outside Matthew’s Gospel—no family testimonies, no graffiti proclaiming “Grandpa’s Back!” The Jewish authorities, who scrutinized Jesus’ followers for any hint of blasphemy, would’ve had a field day with this. Instead, crickets.

Even more puzzling is the silence from the other Gospel writers. Mark, the earliest, focuses on Jesus’ resurrection but skips the undead parade. Luke, the meticulous researcher who “double-checks census records,” as Matthew teases, omits it entirely. John, with his lofty “In the beginning was the Word” framing, doesn’t bother. If this was a major proof of Jesus’ divine power, why didn’t they include it? One possibility, as skeptics suggest, is that Matthew’s account is a theological embellishment, a dramatic flourish to underscore Jesus’ victory over death. The dialogue captures this tension, with John suggesting an allegorical spin and Luke despairing over the lack of consensus: “We’re already arguing over angels versus glowing men versus allegories!”

The Oral Tradition Excuse

One explanation for the delay and discrepancies is that early Christians relied on oral tradition. Stories were told, retold, and embellished around campfires and in house churches. This wasn’t unusual—oral cultures were common, and memory was a trusted tool. But as the dialogue humorously suggests, oral tradition has its limits. By AD 53, the Gospel writers were already bickering over details: one angel or two? A young man in a white robe or a glowing allegory? Luke’s frustration—“If we don’t write this down soon, people will be saying Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a flying donkey!”—highlights the risk of distortion over time.

Oral tradition also doesn’t explain the silence on the risen saints. A mass resurrection isn’t a minor detail you forget to mention, like misplacing a sandal. It’s the kind of event that would’ve dominated every sermon, every testimony. Yet only Matthew, writing decades later, includes it, suggesting it may have been a later addition to emphasize a theological point rather than a widely attested fact.

A Historical Head-Scratcher

The delay in writing the Gospels and the curious case of the missing zombie accounts raise fascinating questions. Were the Gospel writers, as the dialogue imagines, just too busy with mission trips and olive oil spills to write sooner? Did they assume, as John muses, that Jesus’ return was imminent, making memoirs “wasteful”? Or does the silence—both from external historians and the other Gospels—hint at something else, like embellishment or selective storytelling? If a God wanted His will to be unequivocally known, the decades-long gap and inconsistent accounts seem like an odd way to go. The absence of records for an event as dramatic as a mass resurrection suggests either an extraordinary oversight or a story that grew in the telling.

In the end, the Gospel writers did get their act together, producing texts that shaped history. But as they clinked their cups in that Ephesus courtyard, the goat bleating in the background, they might’ve chuckled at their own procrastination. “Fine,” Luke declares in the dialogue, “I’ll start writing tomorrow.” Lucky for us, they did—eventually. But the decades-long wait and the curious case of the unrecorded undead leave us wondering: what else got lost in the wait?

A Most Peculiar Oversight:

The Gospel Writers’ Meeting

✶ Warning: the following was written in a comedic, playful tone and calls the allegedly resurrected Jerusalem saints “zombies.” Understand that those outside your ideology may find such events as absurd as you find the miraculous claims of other religions.

Setting: An open-air courtyard in Ephesus, AD 53. Late afternoon sun filters through olive trees, casting dappled shadows on a low stone table. The four Gospel writers—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—recline on threadbare cushions, surrounded by clay cups of watered wine, a half-eaten loaf of barley bread, and a chipped bowl of olives. A stray goat bleats in the distance. An awkward silence lingers, broken only by the clink of cups and the occasional sigh.

Luke: [Pushing a stray lock of hair from his forehead, adjusting his meticulously folded cloak] So… I’ve been mulling something over, and it’s been nagging at me like a splinter. It’s been, what, twenty years since Jesus died and rose again?

Mark: [Leaning back, picking at his teeth with an olive pit] Twenty, twenty-one. Give or take. Time’s a blur when you’re dodging bandits on mission trips.

Luke: [Frowning, setting down his cup with a deliberate clink] Right. So. Has anyone… written it down?

[A heavy silence falls. Matthew freezes mid-sip, wine dribbling onto his beard. John stares intently at a passing cloud. Mark coughs, suddenly fascinated by a crack in the table.]

Matthew: [Wiping his beard, voice cautious] Written what down, exactly, Luke? The parables? The fish-and-loaves thing?

Luke: [Raising an eyebrow, exasperated] No, Matthew. The big stuff. The crucifixion. The empty tomb. The resurrection. Oh, and let’s not forget the bit where dead people climbed out of their graves and strolled into Jerusalem like it was market day. The universe-altering events we’ve all staked our lives on?

John: [Waving a hand airily, his eyes half-closed in mystical contemplation] Ohhh, that. Yes, well, I’ve been meaning to get to it. I’m just waiting for the right… metaphysical angle. You know, something with cosmic weight. Logos and all that.

Mark: [Grinning sheepishly] I’ve got some rough drafts. Mostly about Jesus cursing that fig tree, though. I mean, the man really had it out for that tree. It was personal.

Matthew: [Pointing at Luke, defensive] I thought you were handling it, Luke! You’re the one who’s always interviewing widows and cross-referencing census scrolls. You’re practically a walking archive.

Luke: [Throwing up his hands] Gentlemen! Are we seriously saying that God incarnate was betrayed, crucified, rose from the dead, wandered around for forty days, gave us a world-changing commission… and not one of us thought, “Hmm, maybe I should jot that down before I forget whether it was a Sunday or a Monday”?

Mark: [Shrugging] I was going to, honest! But then Paul dragged me to Cyprus for that mission trip. Total chaos. Bandits, shipwrecks, some guy named Bar-Jesus causing a ruckus. No time for parchment.

Matthew: [Scratching his head] I started once. Got a few lines down about the Sermon on the Mount. But then I spilled olive oil on the scroll, and it… well, it turned into more of a salad recipe. [Pauses, nostalgic] Actually, it was a great recipe. Garlic, a hint of lemon…

John: [Leaning forward, earnest] Look, I didn’t think we’d need to write it down. I mean, Jesus said He’d be back soon, right? I figured, why waste good papyrus on a memoir when the sequel’s practically tomorrow? Plus, I’ve been busy having visions. They’re very… distracting.

Luke: [Pinching the bridge of his nose] Fine. But what about the resurrection of the saints? You know, the part where tombs cracked open and dead people wandered into Jerusalem? That’s not exactly a minor detail. It’s a bit… [gesturing wildly] zombie apocalypse! And no one thought that merited so much as a footnote?

Mark: [Blinking, genuinely confused] Wait, that actually happened? I thought that was just a rumor! You know how Jerusalem is—gossip spreads faster than leprosy.

Matthew: [Nodding slowly] Oh, it happened. I saw Old Man Zechariah shuffling down the street, looking confused but surprisingly spry for a corpse. I just… didn’t know how to write it without sounding unhinged.

John: [Chuckling] Try writing “In the beginning was the Word” without sounding unhinged. I’m telling you, it’s all about framing. Maybe we call the zombie thing… “a divine procession of the formerly deceased”?

Luke: [Sarcastic] Oh, brilliant, John. That’ll really clarify things for the churches in Galatia. [Sighs] Look, we need to get this down. People are already mixing up the details. I heard someone in Antioch say the empty tomb was guarded by a talking angel. A talking one!

Mark: [Snorting] That’s ridiculous. It was two angels, and they didn’t talk. They just… glowed aggressively.

Matthew: [Perking up] Wait, two angels? I could’ve sworn it was one. And he rolled the stone himself. Strong fella.

John: [Smirking] You’re both wrong. It was a young man in a white robe. Probably symbolic. I’m leaning toward an allegory of divine purity.

Luke: [Groaning] This is exactly my point! We’re already arguing over angels versus glowing men versus allegories. If we don’t write this down soon, in fifty years, people will be saying Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a flying donkey!

Mark: [Laughing] Okay, but that would’ve been awesome. Can we add that?

Matthew: [Grinning, grabbing a piece of bread] I’m in. Flying donkey, glowing angels, zombie parade. Let’s make it a bestseller.

John: [Sipping his wine, dreamy] And I’ll start with the cosmic stuff. “In the beginning…” It’s got a nice ring to it.

Luke: [Standing, resolute] Fine. I’ll start writing tomorrow. But you all owe me. And if I hear one more person call the resurrection “that time Jesus took a long nap,” I’m quitting.

[The group laughs, clinking their cups. The goat bleats again, as if in agreement. Somewhere in the distance, a rooster crows, and they all flinch, remembering another night entirely.]

Leave a reply to J Cancel reply