God’s Contradiction: The Theological Dissonance Between Sinful Suffering and Medical Redemption

I. Introduction

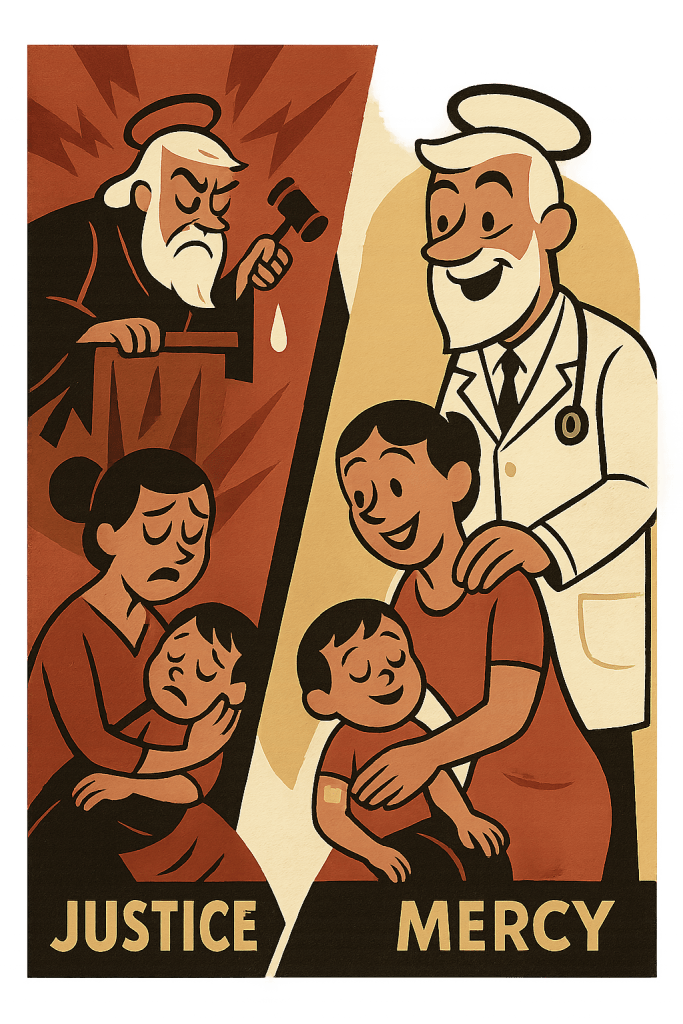

Christian theology presents a tension that many adherents overlook or avoid articulating: the simultaneous affirmation that suffering is the just consequence of human sin, and that the discovery and use of medicine to eliminate suffering is part of God’s loving providence. These two commitments are not merely in tension—they are in direct logical conflict. If suffering is just, then its removal through medicine undermines divine justice. If its removal is good and willed by God, then its imposition was neither necessary nor just.

This essay explores this theological dissonance by examining the doctrinal foundations of suffering as just punishment, the celebration of medical progress as divinely inspired, and the numerous contradictions such a dual framework entails. It concludes that the incoherence is better resolved by rejecting the theological framework altogether in favor of a naturalistic, human-centered understanding of suffering and healing.

II. Suffering as a Just Consequence of Sin: The Theological Foundation

The claim that suffering arises from sin is deeply embedded in Christian theology. The Genesis narrative portrays a once-perfect world corrupted by Adam and Eve’s disobedience. The punishment is not localized—it includes death, disease, toil, and pain (Genesis 3:16–19). This affliction is not merely punitive but hereditary: “through one man sin entered into the world, and death through sin” (Romans 5:12). Theologians like Augustine formalized the doctrine of original sin, asserting that guilt and its consequences are transmitted across generations.

This framing casts God as a just judge, where suffering is neither random nor malevolent—it is proportionate, deserved, and pedagogical. Children dying in infancy, mothers dying in childbirth, and plagues ravaging entire societies are all, under this paradigm, part of a cosmic sentence. As such, they are not anomalies but theological necessities.

III. God as Healer: The View That Medicine Is a Divine Gift

In striking contrast, many believers assert that medicine is a gift from God. Hospitals are named after saints; medical missions are seen as extensions of Christ’s healing ministry; believers pray for healing, thank God when doctors succeed, and view scientific breakthroughs as evidence of divine benevolence.

Verses such as James 5:14 (“anoint the sick with oil… the prayer of faith will save the sick”) and the healing narratives of Jesus (e.g., Matthew 4:24) are cited to support this view. Christianity is thus portrayed as both the source of an account of why suffering exists and the inspiration for its removal.

But this dual claim—suffering is justice, and healing is mercy—is structurally incoherent. And the contradiction intensifies under scrutiny.

IV. Points of Tension and Theological Incoherence

A. Undermining Divine Justice Through Medical Alleviation

If suffering is the just punishment for sin, then alleviating that suffering through medicine implicitly opposes divine justice. One cannot consistently say that God both ordains suffering as a rightful penalty and wants it removed. This is equivalent to a judge who sentences a criminal to 20 years, then funds and celebrates a prison break.

Syllogism A:

P1: If suffering is a just consequence of sin, then its removal is a reversal of justice.

P2: If God wills the removal of suffering through medicine, then God wills the reversal of justice.

Conclusion: Therefore, if God wills medical healing, then He undermines His own justice.

This undermines the internal consistency of divine character claims—justice and mercy become contradictory rather than complementary.

B. The Problem of Timing: Millennia of Silence

If medicine is a divine gift, one must ask why God withheld it for so long. Why did God allow humanity to suffer through millennia of plagues, leprosy, childbirth deaths, and parasitic infestations without even the most rudimentary cures?

To frame it clearly:

Syllogism B:

P1: A being that desires to reduce suffering would not withhold known remedies for thousands of years.

P2: God is said to desire the reduction of suffering through medicine.

P3: God did not reveal such remedies; humans discovered them much later.

Conclusion: Therefore, either God did not desire to reduce suffering, or He is not benevolent or competent.

The timing gap cannot be explained by human readiness, since even basic hygienic practices (e.g., handwashing) were ignored despite being simple, non-technological solutions. Semmelweis was mocked for his handwashing advocacy—by clergy-informed doctors.

C. Natural Evil and Disproportionate Punishment

If suffering is just punishment, then its targets should be moral agents. But disease afflicts infants, the mentally disabled, and even animals—none of whom can sin. Birth defects, genetic disorders, and cancer in children defy any meaningful connection to individual guilt.

Syllogism C:

P1: Justice presupposes moral agency and proportionate consequence.

P2: Infants and animals lack moral agency.

P3: Infants and animals suffer from disease and death.

Conclusion: Therefore, their suffering cannot be just punishment.

This raises the question: is their suffering collateral damage? If so, then God allows the innocent to suffer as a consequence of the guilty—a practice humans rightly consider unjust.

D. Christian Resistance to Alleviating Childbirth Pain

Historical records show that many Christians, especially in the 19th century, opposed the use of anesthesia during childbirth. The reasoning? Genesis 3:16: “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children.” This was interpreted to mean that pain in childbirth was a divine punishment for Eve’s sin—and thus should not be mitigated.

✓ In 1847, James Young Simpson introduced chloroform as a pain reliever in obstetrics. Many clergy condemned it as interfering with God’s decree.

✓ Even prominent theologians argued that using anesthesia during childbirth was an act of defiance against divine justice.

This history exposes the incoherence of simultaneously claiming God wants us to reduce suffering and insisting that some suffering must remain untouched out of respect for divine judgment. Is medicine an act of compassion or an act of rebellion?

E. Human Discovery, Not Divine Revelation

Medical progress has overwhelmingly come from secular science, not divine revelation. The Bible offers no germ theory, no vaccine model, no surgical methods. Every significant advance—Pasteur’s germ theory, Fleming’s penicillin, Jenner’s smallpox vaccine—emerged from empirical observation, often in tension with church doctrine.

Syllogism D:

P1: If God wanted to eliminate suffering through medicine, He would have revealed key insights when they were needed most.

P2: God did not reveal such insights; humans discovered them through secular means.

Conclusion: Therefore, medical progress is better attributed to human inquiry than divine intention.

If God “wanted” medicine to thrive, why did it flourish only when religious institutions lost epistemic control?

F. Selective Attribution: Confirming the Positive, Ignoring the Negative

Believers thank God when healing occurs but blame sin, Satan, or invoke mystery when it fails. This asymmetry creates an unfalsifiable belief system immune to counter-evidence.

Example: A child recovers from surgery—“God answered our prayers!” A child dies—“God had a mysterious plan.” This theological elasticity lacks explanatory power.

Syllogism E:

P1: A consistent explanatory framework treats successes and failures under the same principle.

P2: Christian theology attributes success to God but failure to mystery or sin.

Conclusion: Therefore, Christian explanations for suffering and healing are ad hoc and inconsistent.

V. Counterarguments and Their Rebuttals

➘ “Medicine is God’s grace, not human entitlement”

This view suggests that while suffering is just, God occasionally relieves it out of mercy. But this reduces divine justice to an arbitrary and retractable punishment—like a judge who imprisons the innocent but occasionally grants parole on a whim.

➘ “Healing reflects God’s mercy, not His justice”

But mercy without repentance undermines the entire concept of justice. If a suffering baby receives divine healing despite having no moral standing, that contradicts the claim that suffering is punishment for sin.

➘ “Jesus healed, showing God wants healing”

Jesus’ healings were limited, anecdotal, and did not alter the long-term trajectory of human suffering. He did not eliminate smallpox or cholera; he didn’t provide sanitary guidelines. At most, these stories show isolated acts of compassion, not a systemic plan.

VI. A Coherent Alternative: Naturalism

The naturalistic view treats disease and suffering as biological consequences of living in an indifferent universe. Medicine is the result of human ingenuity, not divine providence. Under this view:

✓ Suffering is neither deserved nor decreed—it simply is

✓ Healing is a human triumph over entropy and biology

✓ There is no contradiction between striving to heal and acknowledging the causes of disease

This framework avoids all the tensions discussed above. It does not require us to believe that the same being who imposed disease is now praised for helping us fight it.

VII. Conclusion

The belief that human suffering is both a just consequence of sin and something God wants eliminated through medicine is not merely paradoxical—it is incoherent. If suffering is deserved, healing undermines justice. If healing is desired, then suffering is gratuitous. These contradictions are intensified by the historical delay in medical knowledge, the indiscriminate nature of affliction, and the fact that healing comes through human effort, not divine revelation.

The theological tension collapses under scrutiny. A coherent view of suffering and healing must reject either divine justice or divine benevolence. Or better yet, reject the divine explanation entirely.

✶ Symbolic Logic Formulations

1. Contradiction Between Divine Justice and Medical Alleviation

Let:

S(x) = x is suffering

J(x) = x’s suffering is a just punishment for sin

D = God desires the alleviation of suffering through medicine

A(x) = x’s suffering is alleviated by medicine

Core Argument:

Contradiction arises from holding both J(x) and D.

2. Temporal Inconsistency of Divine Benevolence

Let:

B = God is benevolent

R(t) = Medical knowledge is revealed at time t

N = Human suffering exists prior to t

T_early = Primitive human history

Core Argument:

The delayed arrival of medical knowledge contradicts divine benevolence.

3. Injustice of Suffering in Non-Moral Agents

Let:

M(x) = x is a moral agent

P(x) = x deserves punishment

S(x) = x suffers

Core Argument:

Therefore, at least some suffering is not just punishment.

4. Human-Origin vs. Divine-Origin of Medical Knowledge

Let:

H = Humans discover medicine empirically

G = God reveals medicine supernaturally

P = Medical progress occurs

Core Argument:

Medical progress arises from human inquiry, not divine revelation.

5. Selective Attribution Fallacy

Let:

R = Recovery occurs

F = Failure to recover occurs

C(x) = x is caused by God

Core Argument:

Asymmetric attribution leads to a non-falsifiable and epistemically vacuous model.

6. Naturalistic Coherence

Let:

S(x) = x is suffering

N(x) = x is naturally caused

M(x) = x is mitigated by human effort

Core Argument:

The naturalistic model preserves explanatory coherence without contradiction.

Leave a comment