Resurrection Stories Make More Sense as Human Psychology Than Divine History

One of the most common lines you’ll hear in Christian apologetics goes something like this: “The disciples had no motive to lie. Why would they endure persecution, ridicule, and even death unless the resurrection was true?”

It’s a powerful soundbite. And for centuries it has convinced countless believers that the resurrection narratives in the Gospels must be grounded in literal history. But if we take a step back and ask not only what happened but how human beings tend to respond when their expectations collapse, a very different picture emerges—one that feels both familiar and, frankly, much more plausible.

The Setup: Hopes and a Crushing Defeat

Imagine walking away from your job, your family, and your reputation because you’re convinced you’ve found the long-awaited leader who will finally bring justice, overthrow oppression, and usher in God’s kingdom. This was the reality for Jesus’ disciples. They expected triumph. They expected vindication. They expected to be on the winning side of history.

In symbolic shorthand, we can call this expectation : “Jesus will be the victorious Messiah.”

And then came the cross. Instead of victory, they got humiliation. Instead of a throne, they saw an instrument of Roman torture. The very event that should have proven them right ended in public shame. That contradiction was : “Jesus was crucified as a criminal.”

Put and

together, and what do you get? Not just disappointment. You get something deeper and more destabilizing: cognitive dissonance, or

.

Why Dissonance Matters

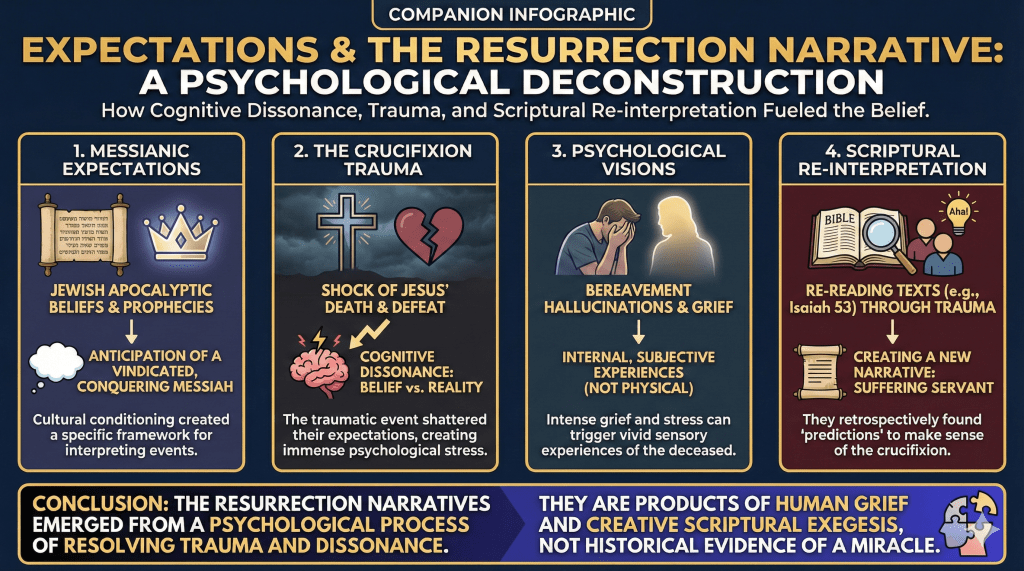

Psychologists have studied cognitive dissonance for decades. Leon Festinger’s classic book When Prophecy Fails followed a UFO cult in the 1950s whose prophecy of the world’s destruction never came true. You might think the failure would destroy the movement. But the opposite happened: the group reinterpreted the failed prophecy as proof that their faith had actually saved the world, and they became even more zealous.

This pattern isn’t unique. When deeply held expectations collide with crushing disconfirmation, people don’t always walk away. Instead, they feel intense psychological pressure—what we can call —to make sense of the contradiction.

For Jesus’ followers, abandoning their expectation wasn’t just admitting a mistake. It would have meant their lives, sacrifices, and identities had all been wasted. That’s not an easy pill to swallow.

How Reinterpretation Works

So, under , the disciples did what human beings everywhere tend to do: they reinterpreted reality. Let’s call this reinterpretation

.

Instead of seeing the crucifixion as a humiliating defeat, they reframed it as a divinely necessary step. The scriptures were re-read. Prophecies that once seemed unrelated were now seen as predicting a suffering servant or a vindicated righteous one. The story was rescued by transforming loss into destiny.

But reinterpretation alone isn’t enough to sustain belief. Something had to make this reframing feel real. And here is where human psychology provided another layer.

The Role of Visions and Grief

In moments of grief, people often experience vivid sensations of the presence of their lost loved one—seeing them, hearing their voice, even feeling their touch. Psychologists call these bereavement phenomena, and they are surprisingly common. We’ll call them .

Some disciples reported such experiences. In the heat of grief, these felt like encounters with Jesus himself. And within the community, they were interpreted as resurrection appearances, or . These visions and bereavement experiences reinforced the reinterpretation

, making it feel experientially validated.

Now, add one more crucial element: communal reinforcement, . In a tight-knit group, stories grow, retelling deepens conviction, and doubts are often suppressed in favor of solidarity. Over time, these experiences crystallized into shared tradition,

.

From Defeat to Tradition

So let’s put the pieces together.

- Expectation:

= “Jesus is the triumphant Messiah.”

- Disconfirmation:

= “Jesus was crucified in shame.”

- Resulting dissonance:

.

- Pressure to reinterpret:

.

- Reinterpretation:

= “The crucifixion was part of God’s plan.”

- Confirming experiences:

+

.

- Amplification through community:

.

- Stabilized tradition:

.

The outcome? The Gospels are best explained as postdiction

: stories reshaped by the interplay of

.

Why This Matters for Apologetics

Christian apologists often say: “The apostles had no motive to lie.” But notice what’s missing here. The disciples didn’t need to lie. They didn’t have to sit down and fabricate a story they knew was false. Instead, the resurrection narratives emerged naturally through the way human beings process grief, dissonance, and failed expectations.

In logical shorthand:

The resurrection accounts are better explained by

(postdiction) than by

(historical resurrection).

Why This Story Feels Familiar

Once you see it, you realize this isn’t just about the first century. We see similar patterns throughout history. Prophetic movements whose predictions failed often reinterpret disappointment as hidden victory. Groups that suffer devastating losses often transform those losses into symbols of purpose. It’s not a sign of dishonesty—it’s a sign of being human.

The disciples weren’t villains. They were ordinary people coping with extraordinary disappointment. Their loyalty, their grief, and their need for meaning drove them to reframe humiliation into glory. The resurrection story is less about supernatural history and more about the resilience of human psychology.

Final Reflection

Seen in this light, the resurrection accounts don’t lose their power—they simply shift their meaning. They are not neutral reports of an objective miracle, but powerful windows into how communities rework despair into hope. The Gospels tell us less about divine intervention and more about the human drive to salvage purpose when everything seems lost.

And that is why, far from proving the literal resurrection, the very structure of the stories points us back to the patterns of human cognition, emotion, and community—the same patterns that shape stories of hope in every age.

A Probability Check: Which Story Fits Better?

It’s one thing to say the resurrection stories look like postdiction. But can we put this to the test in a more systematic way? That’s where probability comes in.

Think of it this way: when we’re weighing two explanations, the key question is: Which explanation makes the evidence more likely?

Our two hypotheses are:

: The Gospels grew out of postdiction, grief, visions, and communal reinforcement.

: The Gospels report an actual historical resurrection.

And the evidence we have—call it —includes things like:

- The Gospels were written decades later.

- They are saturated with scriptural “fulfillment” themes.

- They differ and grow more elaborate over time.

- The first resurrection claims are visionary experiences, not empty tomb reports.

- External corroboration is thin to nonexistent.

- Yet the community doubled down after failure, just as Festinger’s UFO group did.

Now, the likelihoodist question is: which hypothesis, or

, makes all of this evidence

more expected?

Formally, we ask about the ratio:

This is called a Bayes factor. If it’s much greater than 1, the evidence favors over

.

Working It Through

For example:

- Under

, we’d expect grief-related visions and reinterpretations. Under

, we’d expect straightforward reporting of a bodily resurrection.

- Under

, we’d expect decades-late writing as stories matured. Under

, it’s less clear why the main accounts would be delayed.

- Under

, we’d expect different communities to generate variations. Under

, we’d expect more consistency.

- Under

, we’d expect lots of scripture-wrapping to make the story feel inevitable. Under

, this isn’t necessary—if a miracle happened, the event itself would be evidence enough.

On point after point, the evidence looks more like what predicts.

Even if you assign generous credit to on some features—for instance, the disciples’ sincerity under persecution—the combined likelihoods tilt heavily toward

. In rough terms, the Bayes factor lands in the hundreds to one in favor of postdiction.

What That Means

This doesn’t mean the disciples were dishonest. It means that the psychological and social explanation does a far better job of accounting for the evidence than a literal miracle.

Put simply:

In plain English: once you weigh the evidence, the postdiction hypothesis is vastly more probable than the resurrection hypothesis.

So the old apologetic slogan—“they had no motive to lie”—misses the real issue. The disciples didn’t need to lie. Human psychology, grief, and communal storytelling did the work for them. And that is not just a good story. It’s the explanation that actually fits the evidence.

See also:

◉ The Symbolic Logic Formalization

A Companion Technical Paper:

See also:

Leave a comment